The Vision

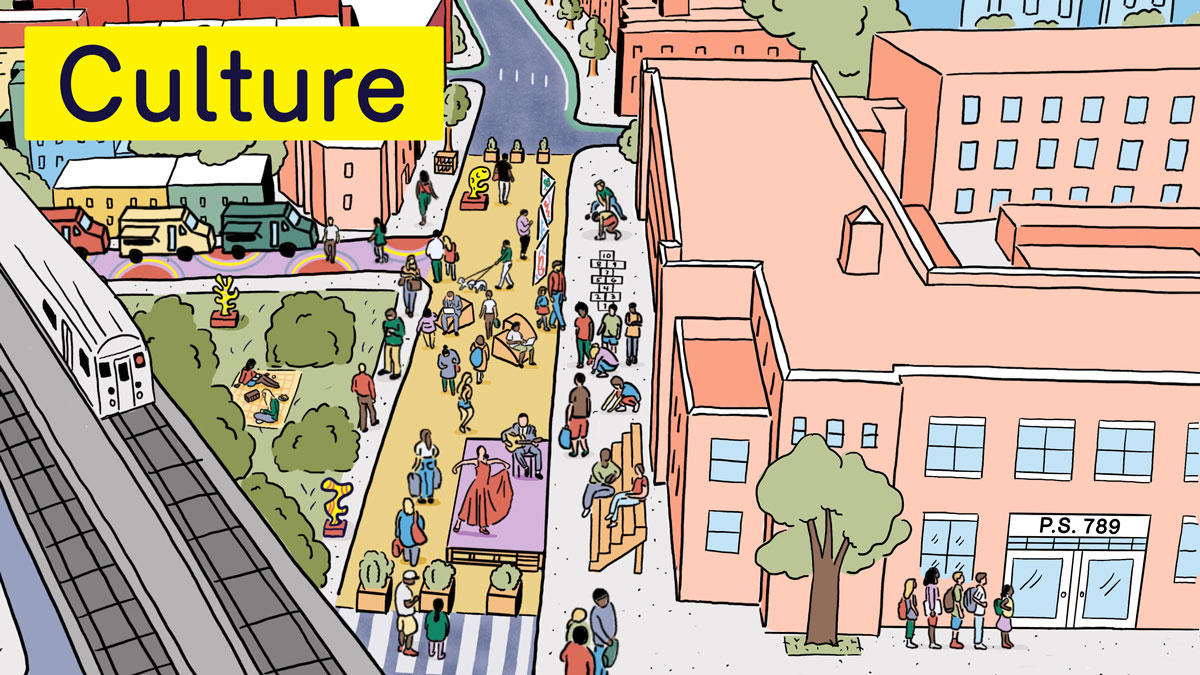

Safe streets don’t only protect pedestrians from traffic violence. They focus on the daily experiences of children, older adults, Black and brown people, and people with disabilities who are often at higher risk in the public Right of Way.

As Open Restaurants blossomed in the summer of 2020, sidewalks and parking spaces transformed into new space for dining and gathering safely. But structures and seating arrangements that now claim the roadway have also created a new maze of obstacles that add to the challenges that New Yorkers with disabilities already face in public space.

For centuries, cities have been designed for able-bodied people. Historically, the lack of genuine inclusive community engagement in design has resulted in a built environment that is inaccessible and unwelcoming to many. And now, as New Yorkers navigate an increasingly complex roadway, we are seeing the ways that our streets are becoming even more inhospitable.

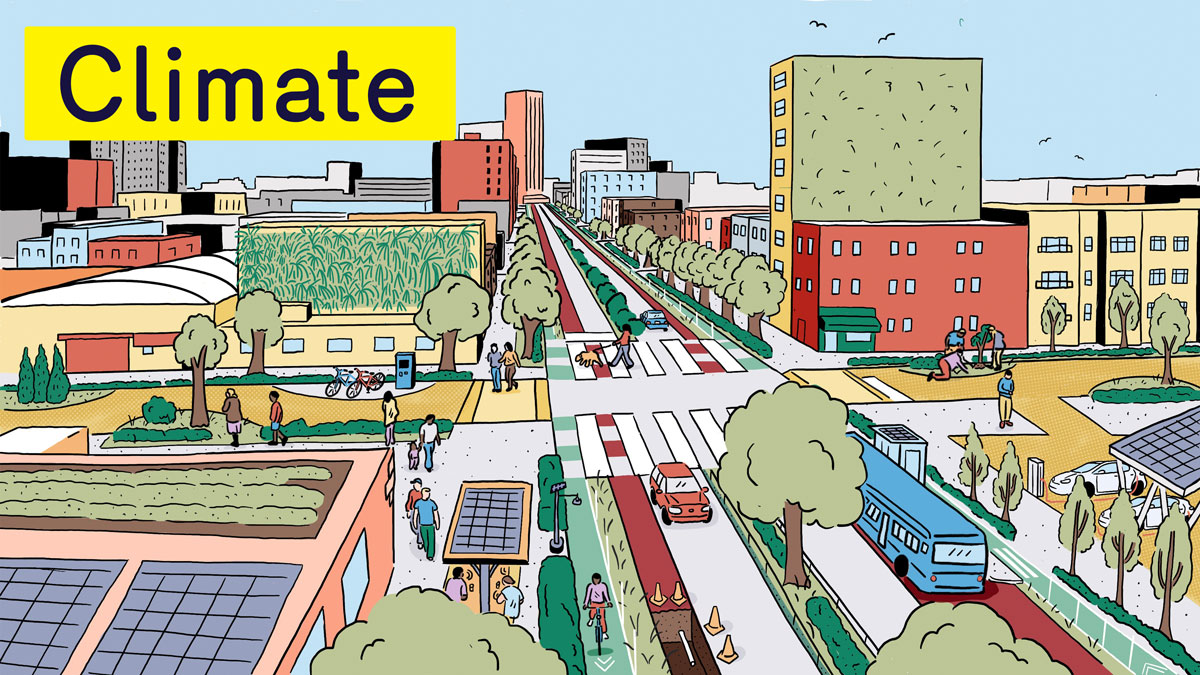

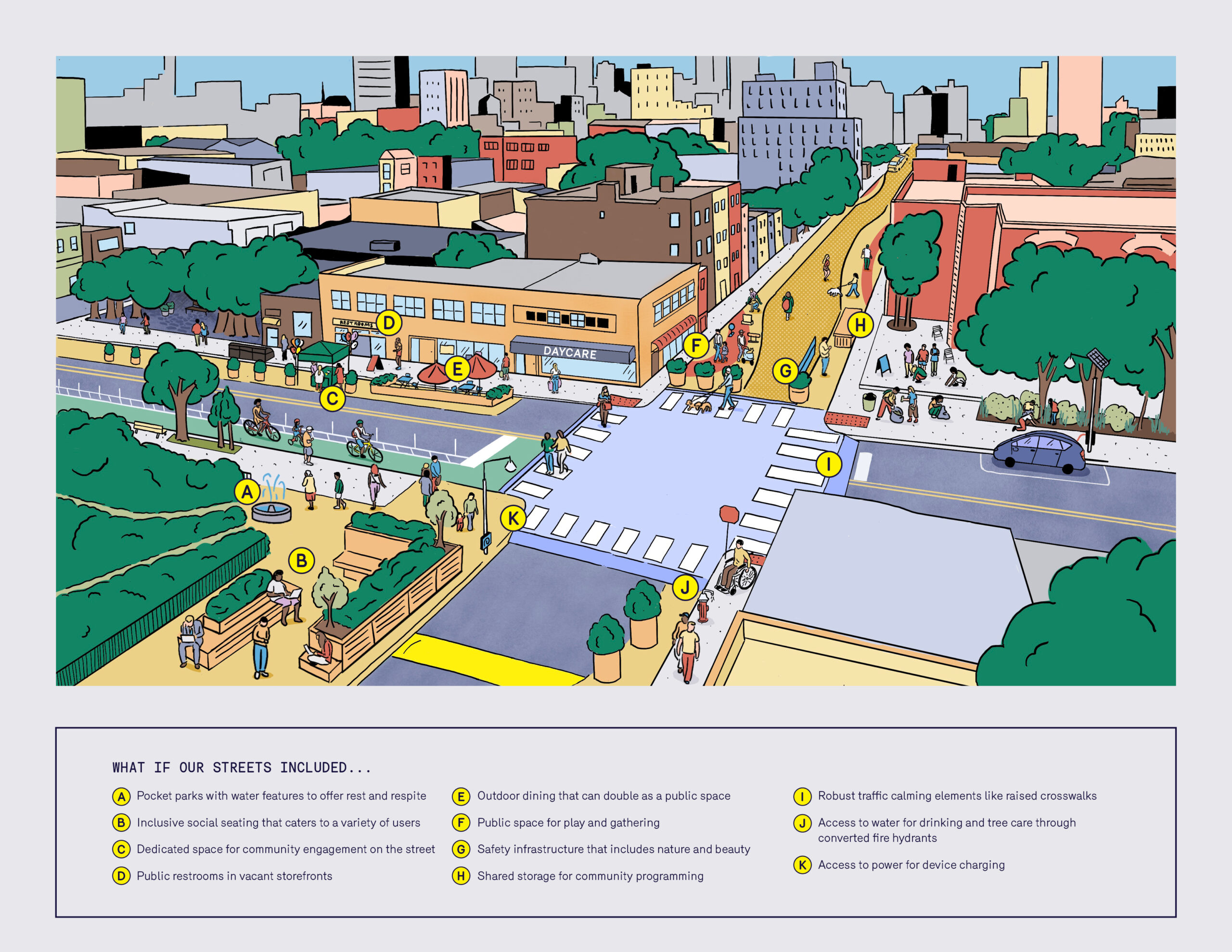

Our vision for Care Streets centers safety, care, and healing for New Yorkers of all ages, races, and abilities. Care Streets should cater to the needs and priorities of people with disabilities from early on in the design process, broadening our definitions of accessibility beyond provisions for people with physical impairments to include mental health (like neurodiverse New Yorkers). The Right of Way should be designed by and for the New Yorkers that use it. Care Streets are flexible and provide a variety of essential amenities, from shade, quiet areas and seating, to basic utilities like drinking water, wifi, and charging power. They are maintained and cared for with community members, supporting better mobility, cleaner streets, and safer neighborhoods.

Recommendations

1. Fund long-term, ongoing and inclusive engagement for street design.

Our street design processes should be inclusive of those who may not be design- or policy-fluent, or tech-savvy. By 2030, the City should leverage funding from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) – following the example of the Kresge Foundation – to support community-led visioning and engagement processes for streetscape transformation projects and programming.

ACT NOW: Expand DOT’s Street Ambassador program.

In 2023, DOT could expand the Street Ambassador program to facilitate better community engagement that accounts for barriers to participation like language, childcare, design and policy fluency. Teams could utilize high-tech and low-tech on-site tools such as augmented-reality, polling, and participatory mock-ups.

ACT NOW: Pilot field offices in every community district.

The City could work with community-based organizations to establish local engagement hubs or “field offices” that will support more ongoing engagement from all City agencies in the neighborhoods they help to shape. Look to examples like the Field Office created through Neighborhoods Now, or to City initiatives to launch IDNYC, Culture Pass, NYC Census, and more.

ACT NOW: Expand Participatory Budgeting to fund community-driven street projects.

The City Council could expand the participatory budgeting program across every council district and prioritize community-driven street activations.

2. Transform streets adjacent to NYCHA campuses.

Drawing on principles laid out in NYC Housing Authority (NYCHA)’s Connected Communities Guidebook, DOT could partner with NYCHA, NYC DOT could partner with NYCHA to create shared and pedestrianized streets adjacent to campuses that would support increased physical activity, reduce speeding, and enhance social connectivity.

ACT NOW: Launch Phase III of NeighborhoodStat.

In 2023, the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice could partner with DOT to include streets adjacent to NYCHA campuses in the next iteration of the NeighborhoodStat Action Plan Agenda. Resources could be allocated to resident-designed solutions for community safety and well-being, like play spaces, lighting, and seating.

3. Strengthen focus on accessibility of the streetscape.

While some new uses of street and sidewalk space have increased accessibility, others have made the public realm less accessible to New Yorkers with disabilities. NYC DOT could work with the Mayor’s Office of Persons with Disabilities (MOPD), DOHMH, and others to incorporate new guidelines for accessibility of the streetscape in the existing Street Design Manual.

ACT NOW: Adapt POPS (Privately-Owned Public Spaces) Guidelines for the Right of Way.

In 2023, DOT could work with DCP to broaden and adapt the use of the guidelines for POPs to account for public amenity zones in the street.

4. Widen the definition of accessibility to include mental health.

The current regulations for accessibility only include accommodations for physical accessibility. By 2030, the City could include design for mental health in an updated version of the Street Design Manual and as a new design consideration in DDC’s Project Excellence Principles.

ACT NOW: Launch a Mental Health in Public Space Task Force.

By 2023, the Interagency Public Realm Working Group should launch a mental health task force, with a mandate to learn from designers, healthcare experts and service providers, to develop a design framework for neurodiverse populations in the public realm framed through safety, accessibility, and mobility.

5. Make bold moves for public infrastructure in the streets.

Many streets lack critical infrastructure for people. Partnering with utility companies and City agencies like DEP and DOT could invest in public amenities like water fountains and access to free wifi in a new toolkit of streetscape improvements.

ACT NOW: Convert hydrants for water access.

By 2023, DOT, DEP, DPR and the NYC Fire Department (FDNY) can expand the Cool Streets program by equipping more neighborhoods with spray cap attachments for hydrants and assembling community stewards like the Hydrant Education Action Teams to support safe use. Additionally, the City can seek proposals from designers to develop new retrofit attachments that convert hydrants for tree care and water fountains.

ACT NOW: Expand LinkNYC and retrofit light poles.

The City could expand LinkNYC stations to previously underserved neighborhoods, partnering with local CBOs to place where most needed. Pilot retrofitting light poles for access to device charging in the Right of Way, and include emergency call buttons that connect directly to a local crisis response team.

6. Develop permanent and accessible bathrooms for all New Yorkers.

As of 2019, there were only 1,103 public bathrooms around New York City, with only two open 24/7 [1]. By 2030, the City could develop public-private partnerships and incentives to fund and maintain staffed public bathrooms. The City could subsidize conversion of ground floor vacant retail space, creating jobs and a source of income for building owners.

ACT NOW: Explore low-cost and temporary solutions for bathroom deserts.

By 2023, the Interagency Public Realm Working Group should launch a public bathrooms task force to implement new designs for accessible restrooms on the street. For highly trafficked neighborhoods, the City could install bathroom trailers to occupy parking spaces in front of vacant storefronts, managed by public-private partnerships.

7. Design multi-use street furniture.

Streets and public spaces are becoming clogged with many one-use items. As new uses from 2020 and beyond become clear, the City could invest in furniture and safety infrastructure that can serve multiple functions and time scales, and house them in a new toolkit of street amenities.

ACT NOW: Source multi-use design ideas.

In 2023, DOT and SBS could host a design competition to pilot new types of flexible street furniture, such as modular seating, safety barriers, and planters to support street usability and biodiversity.

ACT NOW: Pair restaurants and CBOs to share outdoor space.

In 2023, NYC DOT and SBS could pilot a “Street Buddy” program in each borough, pairing restaurants equipped with outdoor dining set-ups with local community and cultural organizations to use the space for civic meetings during the restaurants’ off-hours.

8. Prioritize safety for vulnerable populations.

2021 was the deadliest year of Vision Zero, with record levels of traffic violence killing 273 people in New York City alone. By 2030, the City should expand traffic calming strategies like chicanes, bumpouts, raised crosswalks, and expanded public space that prioritize pedestrian safety and clarify visibility for drivers. The City should prioritize these projects near schools and Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities, learning from interventions like “We Protect Schools” in Barcelona.

ACT NOW: Identify 10 priority Safe Streets.

By 2023, DOT should identify 10 sites for “Safe Streets” to pilot safety measures around schools, churches, and other target areas. Consider undertaking Round 4 of Safe Streets for Seniors to identify additional priorities.

9. Invest in community-led street safety initiatives.

Many challenges such as substance abuse and mental health crises often play out on our streets, and too often fall to police by default. As an alternative, the City could realize a holistic plan to invest in community-led safety initiatives by 2030, equipping community organizations with crisis response teams that include mental healthcare professionals.

ACT NOW: Support community ‘safe walks.’

The City could fund community organizations that administer programs like ‘safe walks’ to accompany residents from subway stations to their homes and offer other supportive services.

10. Fund community groups to increase local street stewardship.

By 2030, the City could increase funding for community stewardship programs, prioritizing resources to smaller outer borough BIDs, block associations, and other community groups to better manage on-the-ground maintenance in pedestrian-focused spaces.

ACT NOW: Launch technical assistance partners for smaller nonprofits and civic organizations.

By 2023, the City could launch a technical assistance partners program that matches well-funded BIDs and conservancies with lower-resourced BIDs and CBOs to share knowledge on streetscape and public space stewardship, taking lessons from the Institute for Urban Parks.