Will technology fundamentally change our public spaces? How should technology change the way we build public space?

Designing Just Spaces

New York Hates You: Trump and the Occupation of Fifth Avenue’s Public Space

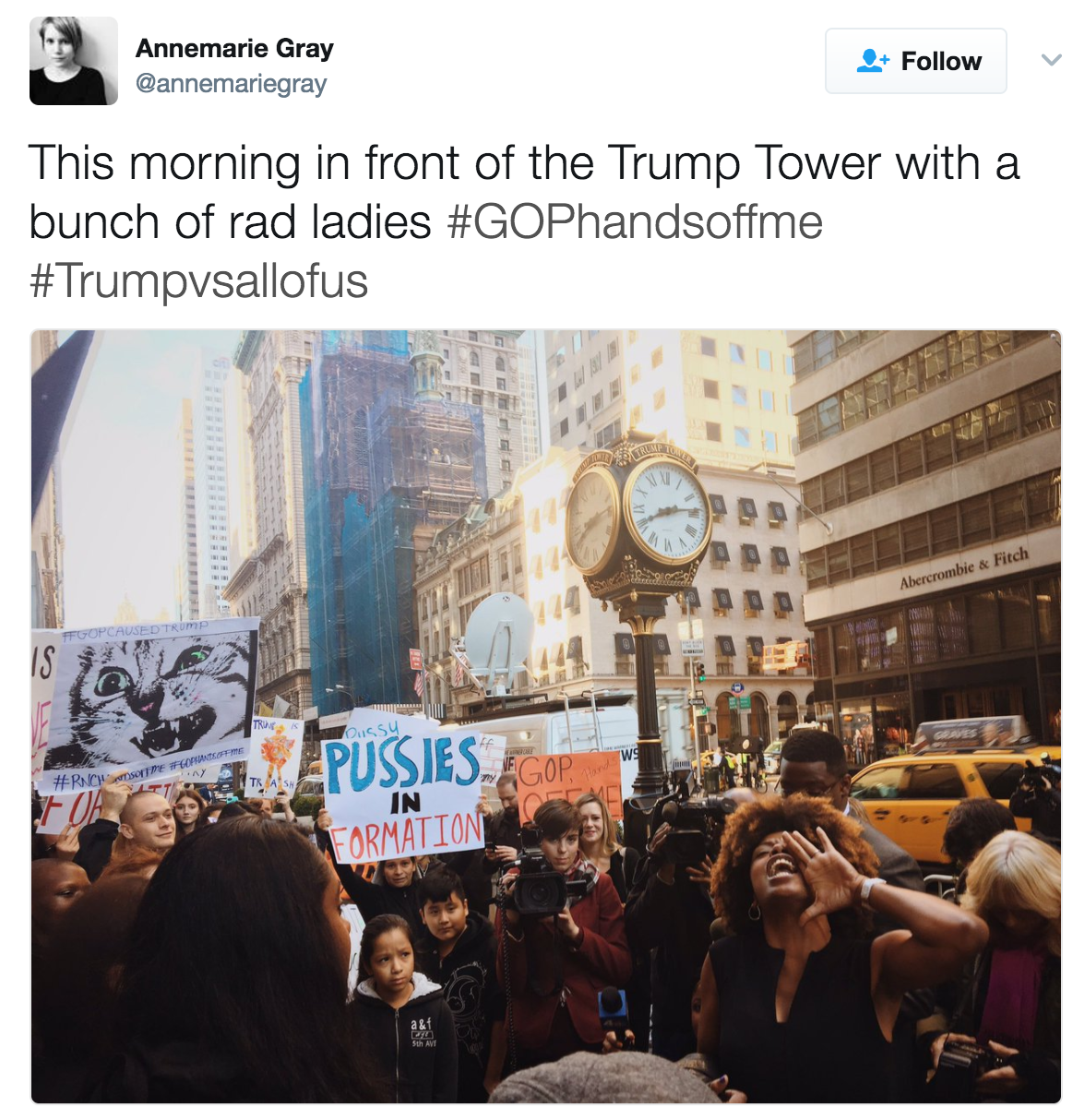

November 9, 2016: the day after the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States, the corner of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-Sixth street became ground zero for a roiling protest that seemed to spring straight from the collective id of a city knocked flat. New Yorkers poured from subways and office buildings, fueled by anger, grief, disbelief, and the drive to show what could only be shown collectively: the city’s wholesale rejection of the President-Elect. Their destination was Trump Tower, whose looming, opaque black glass stood in contrast to the small-d democratic human expression unfurling below. That day, Fifth Avenue became a new public space – packed with bodies, hashtagged, and forever changed in its city’s collective memory.

Protests outside of Trump Tower on November 9, the day after the 2016 Presidential election. (Wikimedia Commons)

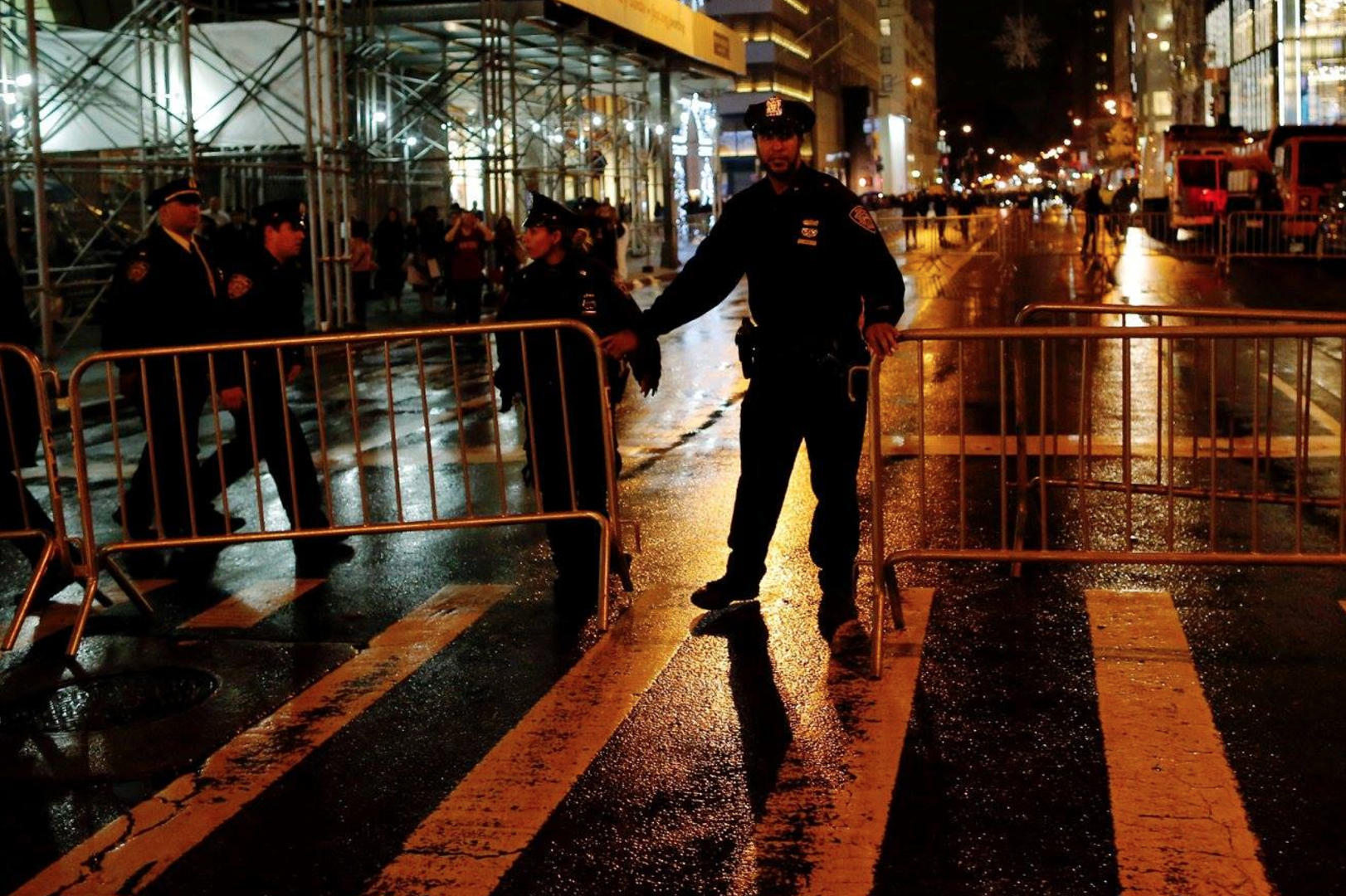

By the inauguration, the streets and sidewalks surrounding the tower were reconfigured as a makeshift security zone, whose impenetrability was indicated by Jersey barriers, the architecture of accidental permanence. Secret Service agents, heavily armed NYPD officers, and private security guards staffed checkpoints at the perimeter. Fifty-Sixth Street was indefinitely closed to traffic. Gawkers and selfie-takers, bearing middle fingers or red baseball caps, became as permanent a fixture of the streetscape as its lightposts. The street had transformed once again: in both physicality and meaning, it had left its ordinary state through a chaos defined by public sentiment, before being reclaimed as a security space, public in name only.

“The right of people from all parts of society to meet their fellow-citizens in the public space is a basic pillar of democracy.”

— Jan Gehl“I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters.”

— Donald Trump

New York’s street design is pragmatic above all else. A Manhattan street is a public place designed for function, not expression, for efficient commerce and egress, not specifically for public gathering. Fifth Avenue, one of New York City’s most identifiable public spaces, is not known as a palette for public dissent. Although it’s “bustling” — the most Manhattan of qualities — it’s less an agora than a utilitarian thoroughfare and a shopping district. In the mental map of the city, it’s most synonymous with high-caliber consumption, material desire, and upward-mobility tourism. What does it mean when such a narrow definition of “public” is blown up by mass protest, and then further narrowed through security protocol?

Before November 9: An increasingly private public space

As a public space in Midtown Manhattan, Fifth Avenue before November 2016 was far from simply “public.” Its five lanes of downtown-bound traffic are flanked by wide, sidewalks on which pedestrian traffic is heavy but commerce, from flashy advertising to sidewalk vending, is dominant. As is common in Midtown, the line between public and private space has long been blurred here. Sidewalk-adjacent public plazas can seem insincere attempts to accommodate theoretical gathering, while somewhat hidden Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS) are tucked into the atriums of office towers. Both are nominally public concessions built by developers in exchange for a height variance, and they are typically treated as afterthoughts. The POPS within Trump Tower (whose context and meaning is expertly dissected by Karrie Jacobs in Architect Magazine) is a badly-marked labyrinth of atrium-level space with minimal seating, and often-closed balconies on higher floors. The poor signage and limited amenities of this space represent the rule, rather than the exception, for Midtown POPS.

Privately owned public space in Trump Tower (Wikimedia Commons)

This stretch of Fifth Avenue is one of the “great walks” of Manhattan; its intact streetwall, consistent activity and reliable spectacle make it a tourist attraction. It’s long been known as a destination for both window shopping and actual commerce. Both are transactional public activities, with private enterprise defining the parameters of expected and accepted behavior. Whether providing the entertainment or the actual goods, the department stores, chain stores, and boutiques of Fifth Avenue determine the primary use of the sidewalk. In summer months, some even open their doors and provide air-conditioning and music to the sidewalk, literally blurring the atmosphere between public and private. And this forefronting of the private sector is no accident: the Fifth Avenue BID has been working since the 1990s with more than 150 retailers to keep Fifth Avenue from 46th to 61st Street “clean, safe and welcoming,” provide “supplemental security and sanitation services,” and assist tourists along this commercial strip.

As is typical in high-value commercial districts, security and surveillance infrastructure are pervasive. Heavy concrete planter barriers and bollards delineate property lines and define street-level public plazas. A line of barrier planters has stood outside Trump Tower for more than a decade. The district has a visible police presence, including regularly-placed NYPD officers directing traffic. The Fifth Avenue BID employs “Community Safety Officers,” private security staff who double as tourist ambassadors and provide an additional visual symbol of public security. When the officers first hit the street in 1993, then-Mayor Giuliani called it “emblematic of the type of public/private cooperation that yields a win-win-win situation. Communities win, businesses win, all New Yorkers win.”

Trump Tower from the curb (Google Streetview)

The omnipresence of surveillance cameras, though a visible and expected aspect of public urban life, is more difficult to quantify. New York City does not publish the number or location of public or private cameras, although according to most experts, it has risen dramatically in the past two decades. A study by the New York Surveillance Camera Project estimated that visible surveillance cameras on Fifth Avenue in Midtown more than quadrupled in just the year and a half following the September 11 attacks. The New York Civil Liberties Union found that the percentage of surveillance cameras in public spaces in New York rose by 443 percent from 1998 to 2010, and has counted more than 2,400 known public cameras in Manhattan alone. London, which does make its numbers public, has more than 500,000. Speaking on the increasing pervasiveness of both mounted and drone-based surveillance cameras, Mayor Michael Bloomberg told the Daily News in 2013, “We’re going to have more visibility and less privacy. I don’t see how you stop that.” For many New Yorkers, assumed surveillance is increasingly a fact of public life, and a small price to pay for security.

November 9: Emergence of the unruly Fifth Avenue

Even before the 2016 election, the public street and sidewalks of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-Sixth Streets had grown in symbolic significance in the city’s consciousness. Small but fierce flash-protests, organized largely through Twitter and Facebook, had become increasingly frequent during the campaign. Anonymous organizers of actions such as the October 16 “blockade” by women protesting Trump over recently-leaked admissions of sexual assault, mobilized, publicized, and documented their actions through Twitter personas such as @PussyGrabsBack (joined October 2016).

Women’s March on January 21- the day after the Presidential Inauguration (Annemarie Gray via Twitter)

Taking a page from leaderless, social media-driven movements such as the Arab Spring and Occupy, these actions seemed to focus not on getting tens of thousands of participants, but on mobilizing as quickly as possible and disseminating information in real time to affect the news cycle. In effect, these 21st century tactics take an expanded view of the public realm, and public protest, considering online space an equally crucial front for resistance. A meaningful protest movement, it seemed, didn’t require a lot of bodies in the street, but did require a lot of eyeballs.

In the weeks leading up to the election, with more than 90% of Manhattan voters planning on pulling the lever for Hillary Clinton, a Trump victory seemed like a remote and unserious possibility. While NYPD and private security presence had been ramped up at the tower in the final weeks of the campaign, there had been little public or media discussion of the possible impact of four years of Secret Service-level security on either public space or the city’s budget. The inconvenience of security infrastructure on Fifth Avenue appeared temporary, and New Yorkers were used to temporary inconveniences.

It is difficult to overstate the shock felt in New York on the evening of November 8. That evening, much of the real-time initial reaction – the disbelief, the desperate calculations, the anger — took place on social media, our most immediate public realm. But November 9, a cold and rainy day, brought the online reaction into physical space, as waves of protestors headed to Fifth Avenue. The thousands of participants in the first post-election protests had not planned, scheduled, or permitted their participation. Facebook events had been hastily created early Wednesday morning, and many saw images of the growing crowd on Twitter before heading out. Others just knew they would not be alone if they went. The public space at Fifth and Fifty-Sixth had taken on a new urgency overnight; the map of Manhattan in the city’s collective consciousness had undergone a shocking update.

Police outside of Protests on November 9- Election day (Reuters)

Even outside the current reality that crowd-size estimates equate to political clout, it’s difficult to quantify the number of protestors outside of Trump Tower in the two days following the election. Estimates generally range in the several-thousands in Manhattan. Similar unplanned, unpermitted, fast-breaking mobilizations occurred in cities across the country, and around the world. Much like the Women’s Marches and airport protests that followed in January, these distributed protests’ simultaneousness and unified imagery, made possible by social media, were a source of strength for participants.

For twenty-four hours, Fifth Avenue was uncharacteristically unruly. The Trump Tower protests were self-organized, spontaneous, un-permitted, and emotionally charged. Although largely peaceful, sixty-five protestors were arrested on November 9, on charges including “disorderly conduct” and “blocking vehicular traffic.” However, at a certain point in the evening, the NYPD, a police force well-versed in crowd control, seemed to give in to the crush of protestors determined to occupy space outside the Tower, and as long as they remained peaceful, made few attempts to control their flow.

The snapshot of Fifth Avenue immediately following the election was as genuine a public expression of the right to public space as is possible in a highly-securitized, heavily surveilled and psuedo-privatized environment like Midtown Manhattan. The frequent speculation about whether we’re entering a “new era of perpetual protest” is often rendered in optimistic surprise; but what are our public spaces for if not for democratic expression? And does the fact that this expression, in public space, seems so anomalous indicate how far our public spaces have drifted from their purpose?

A few weeks later: Barriers up

By the end of November, the bulk of the initially-visible public outpouring of anguish had moved from Trump Tower to a more recognizable twenty-first century agora: the internet. The resistance took on other forms besides bodies in the street. Larger, more organized actions, such as the Women’s March, were planned. Estimates were assembled regarding the cost to the city of securing Trump Tower for the next four years. Mayor Bill de Blasio feuded with Trump in the tabloids about this cost. The President-elect did little to ingratiate himself to those who had shown up to protest his election, his fellow New Yorkers.

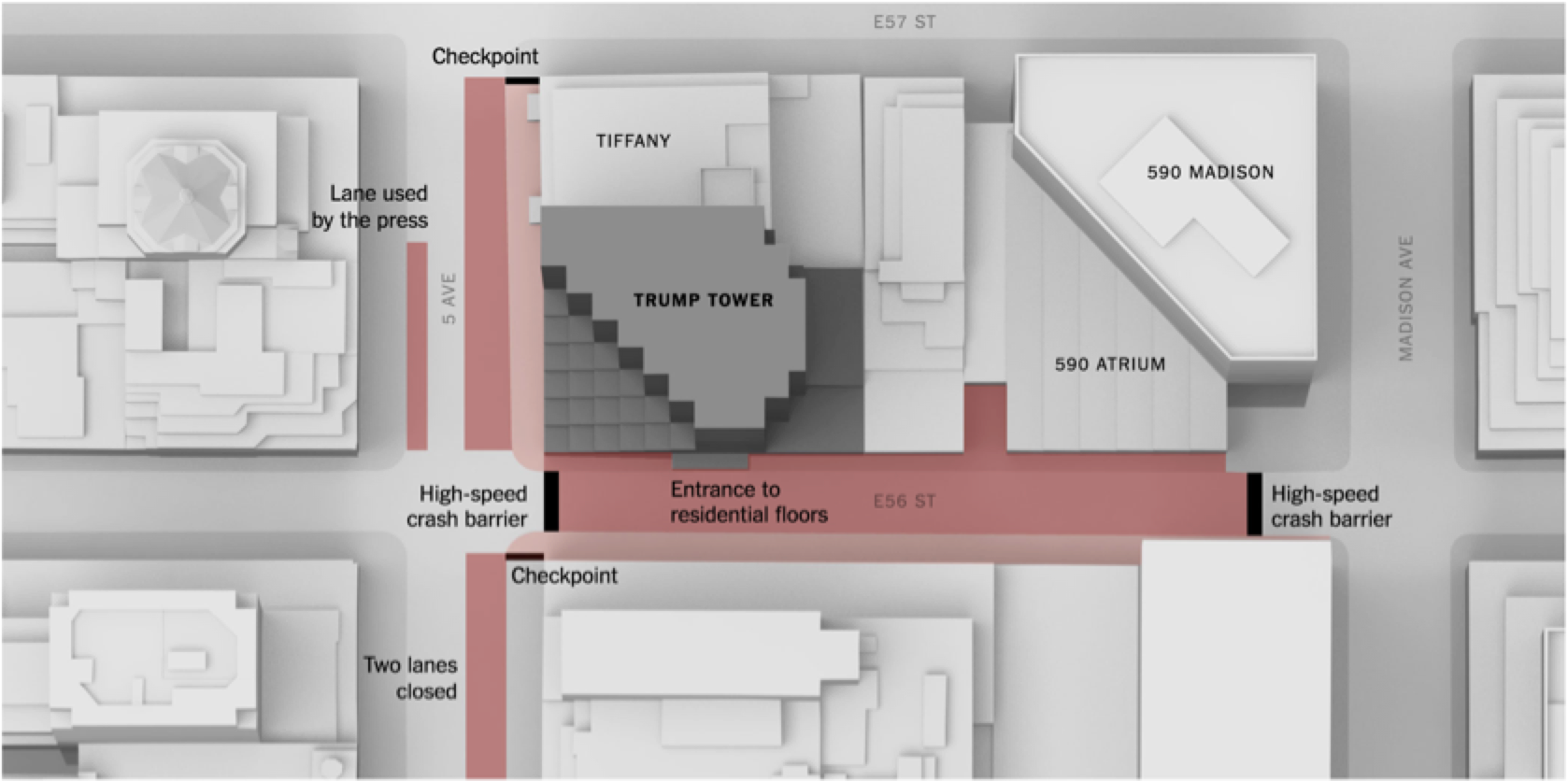

Meanwhile, several rows of metal pedestrian barriers went up around Trump Tower, essentially privatizing the sidewalk. 56th Street between Fifth and Madison Avenues was entirely closed to traffic, and security checkpoint booths appeared at the intersections behind high-speed crash barriers. Three traffic lanes were barricaded off, two for a security buffer and one across the street for a semi-permanent pen for journalists and photographers keeping tabs on visitors to the tower. The new “temporary” security infrastructure invoked permanence in the same fashion as much of Lower Manhattan following September 11. New Yorkers seemed to know what to expect, and the loss of a small sliver of public space in an already questionably-public district seemed to pale in comparison to fears of what the new administration would bring.

Security infrastructure around Trump Tower (New York Times)

Physical public space restrictions aside, the site continued to feature significantly in the city’s collective self image. As the Trump name was being removed from the residential towers on Riverside Drive across town, commercial tenants in Trump Tower and adjacent buildings complained of a drastic decline in foot traffic and a drop in sales. Mayor de Blasio was quoted in the press as saying “I will not tell you that Gucci and Tiffany are my central concerns in life.” However clumsy, this sentiment is telling in its opposition to the fundamental identity of Fifth Avenue, a place that has been more or less defined by high-value commerce.

Also, by the end of Trump Tower had developed its own online persona. Geotagged Instagram posts from the tower contained hundreds of individual expressions of on-location disdain, far outnumbering positive imagery of the location. The raising of a middle finger at a skyscraper might only last a moment in physical space, but its online life is long. In late November, an online “vandal” changed the building’s name in Google Maps to Dump Tower. But the barriers remained up, the visible opposition on-location continued to dwindle, and commuters learned to avoid the security snag as if it were any other obstacle to New York efficiency.

Whose streets?

Public space carries within it a fundamental tension. On one hand it requires predictability to function. Collective orderliness is the assumption that allows us all to surround ourselves with strangers, to commute on transit, to live and to work stacked floor upon floor, to consume at a steady rate without running out of things to consume. Yet on the other hand, by definition public space invites some degree of chaos. People are unpredictable, and public spaces can be visible showcases for the chaos and expression that makes us human.

We are constitutionally granted freedom of assembly, but street design, visible security and surveillance, public-private management agreements, collective memory, and social norms can all contribute to that freedom being exercised infrequently. In order to satisfy egress and commerce, Fifth Avenue, and other commerce-oriented public spaces require that human unpredictability be kept to a minimum. Fifth Avenue was never intended for mass demonstrations. It’s not a marketplace of ideas, it’s a marketplace, and it evidently takes a global-scale systemic shock like November 8 to shift that ingrained identity, even for a few days.

Protests outside of JFK after the Travel Ban Executive Order was signed (Wikimedia Commons)

If we are indeed headed into a new era of mass demonstration, what does that mean for public space? For one thing, the era is likely to be defined by an uneasy and quickly evolving hybrid of online and offline mobilization that will be impossible to accommodate with public space design alone. Rather than Fifth Avenue, the spontaneous immigration ban protests at airports nationwide are perhaps a truer manifestation of this new kind of public assembly. They did not take place in traditional, designated public gathering spaces. Diffuse, immediate, reactionary and viral, it was their speed, their number, and their imageability that made them powerful. It’s difficult to imagine this power coming from a demonstration in even the most thoughtfully-designed public plaza.

If there is a silver lining to the decades-long trend of encroachment on public space of security, surveillance and commercial infrastructure like that surrounding Trump Tower, it’s that our definition of public spaces is broadening beyond the physical to the virtual and the temporal. The tower may now lay claim to some additional real estate, but public expression can now organize in a flash, multiply with a click, and live in a collective memory supported by digital connection.

Designing Just Spaces

The public street is often the stage for all facets of public life. Right of ways house festivals and markets, childhood games, criminal activity, public surveillance, meaningful engagements between neighbors, and provide a space of safe passage for residents and visitors. In essence our streets are spaces for the projection of democratic ideals and discriminatory practices. The purpose of this essay is to explore how certain technological investments in public streets can either reveal layers of injustice, connect people to their civic duties in partnership with government or allow engagement between people and their local businesses.

“Streets and their sidewalks – the main public place of a city – are its most vital organs.”

— Jane Jacobs

In order to ground this research in reality, this essay explores the connection between the public street and urban justice along the stretch of Mother Gaston Boulevard between Livonia and East New York Avenue in Brownsville, Brooklyn.

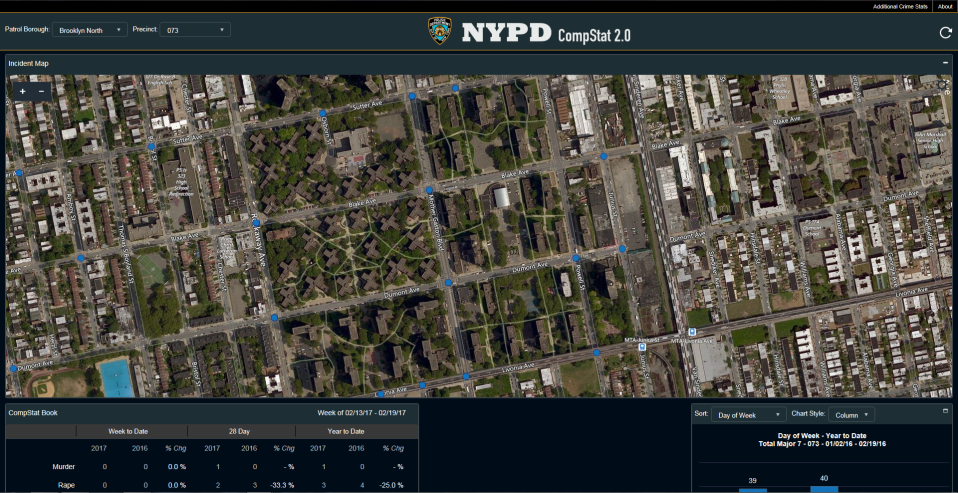

Mother Gaston Boulevard was selected for this analysis because of its unique composition. The majority of the public housing in Brownsville is situated along the Boulevard alongside other public assets, presenting an opportunity for impact through public action. New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) developments along Mother Gaston Boulevard account for nearly 20 percent of all violent crime in public housing. According to CompStat, an online crime management tool for New York City Police Department (NYPD), 2016 statistics various intersections along Mother Gaston Boulevard have been the sites of numerous assaults, shootings and robberies. This is an unfortunate fate for a street that is named after an important historic figure for the community.

Entry to NYCHA housing on Mother Gaston Boulevard (Ifeoma Ebo)

Rosetta “Mother” Gaston was a community activist who dedicated her life to community work and teaching Black children about their heritage. She founded the Heritage House – a community center on the second floor of the Stone Avenue Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, located on the corner of Mother Gaston Blvd and Dumont Avenue. A mural of Mother Gaston was painted on the corner of Pitkin Avenue to honor her legacy, which today serves as a gateway to the beloved Boulevard.

View on Mother Gaston Boulevard to Pitkin Avenue

Technology and the design process

In an interview with Justin Garrett Moore, Executive Director of the Public Design Commission and Adjunct Professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, he discussed the explicit connection between the design, programming, operation, management and policing of public streets, and the people that use, have access to and/or rights to use the streets. Moore connects the advent of tech tools to the socially impactful transformation of the design profession.

The purpose of a designer has been recalibrated and is evolving more out of a process of discovering how people connect to place than to the traditional process of site analysis, schematic design, design development.” With the advent of Building Information Management and other digital imaging tools the experience of designing a street has become more efficient, leaving designers with greater capacity to explore ways of engaging communities in collaborative problem solving through design.

Additionally, the evidence of an “unjust” design process can be tangibly demonstrated in a built environment that does not connect or relate to the needs of the people that use it.

Brooklyn Moving Forward Mural depicting Rosetta “Mother” Gaston (Ifeoma Ebo)

Technology and the participatory design process

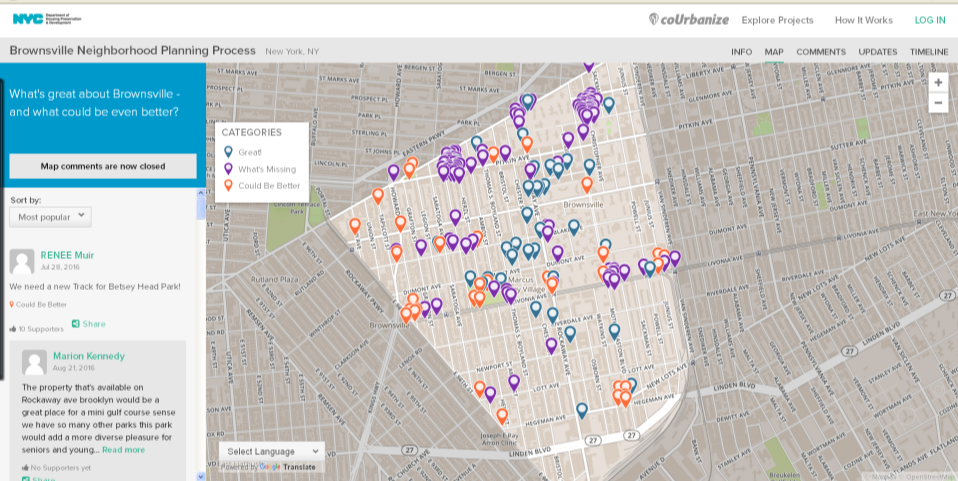

The Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) is using CoUrbanize, an online community engagement platform, to invite residents to participate in the agency’s Brownsville Neighborhood Planning Process. Founded in 2013 by graduates of MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning, CoUrbanize is geared towards people who want to participate in their community’s planning but may not have time or schedule flexibility to attend a meeting. From the comfort of their cell phones, residents in Brownsville can either visit the online platform and provide feedback or contribute to a text messaging service where they can voice ideas that aren’t on the city’s radar. The holistic approach that HPD is taking to decrease vacant space, activate corridors and improve mobility seems to encourage a just process that empowers residents.

The CoUrbanize Platform

Using a technology-based approach acknowledges that many Brownsville residents use these tools as their primary form of engagement within their social networks, relevant organizations and the outside world.

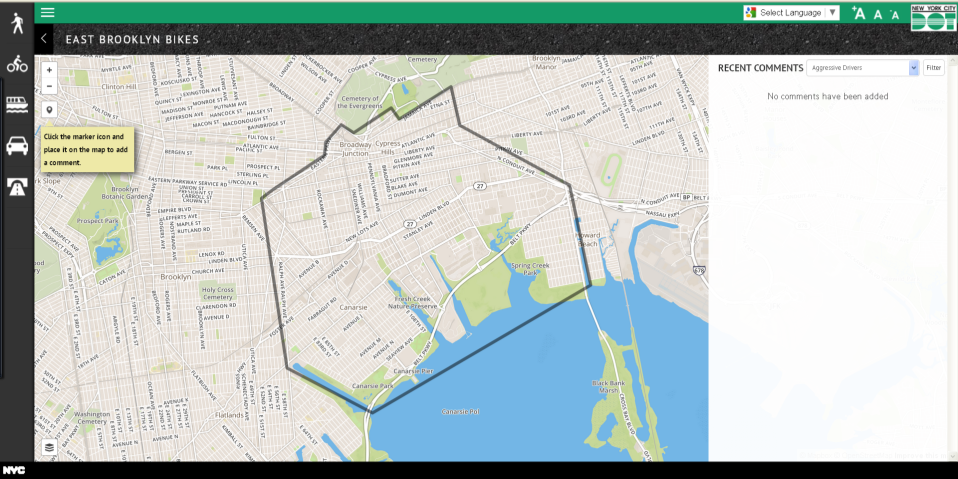

In an effort to promote resident participation in the physical design of streets, the New York City Department of Transportation (DOT) launched the Street Ambassador program in 2015. DOT brings outreach directly to New Yorkers by setting up mobile information stations where DOT projects are being considered or have been implemented to collect ideas and input. According to Patrick Smith, an Urban Designer at DOT, “Street ambassadors are effective because of the use of technology. They use a survey app that makes it more efficient to collect information from locals and store it on a database.” In addition, this database can quickly produce graphs and other visual tools based on the data collected to support the development of policy and planning strategies. Similar to the coUrbanize tool used by HPD, DOT has created their own interactive map where people can post location specific comments. Patrick believes this holistic approach to community engagement technology “provides a midpoint between a community meeting and canvassing the street – it decreases the barriers to obtaining public feedback.”

NYCDOT Feedback Portal

For DOT, public safety is composed of many interconnected parts. Focus on pedestrian safety from vehicular traffic is connected to the improvement of safety from criminal activity. As people feel safer to physically cross the street, they feel more comfortable to walk in the neighborhood and this in effect increases the natural surveillance of the street. However, in the context of Brownsville some residents do not feel safe walking on the streets not because of fear of vehicular traffic, but the fear of discrimination by law enforcement.

Technology and the pedestrian experience

In an interview with Natural Langdon, a Brownsville raised film director, he raises the point that Brownsville streets are a place where youth are conditioned to being physically violated by law enforcement. Grabbed, frisked, and perhaps even taken into custody, their identity transforms on the street: they are criminalized.

Natural Langdon on Mother Gaston Boulevard

This treatment can imprint on the mind of a young child that the public street is a place where they do not belong. This stigmatization of youth in Brownsville is further exacerbated by the presence of NYPD security cameras on Mother Gaston Boulevard which insights fear rather than safety.

According to Langdon, cameras on the street create feelings of being monitored and controlled, a loss of privacy, freedom and ownership – not only for criminals, but for the greater community as well. In Langdon’s childhood, Mother Gaston Boulevard was more often perceived as a space for the amplification of bad activity as opposed to the celebration of the good. However, to address these issues he feels that “what is needed is a safe space for youth to be productive.”

In response to this need for youth empowerment Quardean Lewis founded Made in Brownsville, a nonprofit that implements programs to empower youth through skills training and mentorship. For Lewis, an architect born and raised in Brownsville, the main challenges to justice along Mother Gaston Boulevard are between “access and power – the means to have an impact and define spaces and the authority to govern those spaces” do not belong to the people of Brownsville. These sentiments are evident in the fact that many of the businesses on Mother Gaston Boulevard, particularly in the stretch between Pitkin and Sutter Avenue, are not owned by residents.

Businesses along Mother Gaston Boulevard

This lack of prominent business ownership in Brownsville is unfortunate because the street is the place where community wealth is built as a space for business activity. Additionally, commercial wealth built in Brownsville is not connected to the people that live there. As a result, financial resources are not being recycled in the community. The public street can be a vehicle for the transformation of this paradigm. The connection to and ownership of a place is essential to how people, particularly street owners, treat the street.

In response to this need for wealth building in Brownsville, Lewis is interested in working with his organization of youth to design and launch a new distribution network of touch screen interfaces along public streets that allow for communication between residents, local businesses and nonprofit organizations. Since many local entrepreneurs do not have the capacity to advertise on the street, these touch screens will allow them to reach pedestrians through technology. He hopes that this new tech tool can begin to address the inequity in economic empowerment in the neighborhood; however there remains a challenge to local access to economic power that is connected to limited private ownership along the Boulevard.

NYPD security camera on Pitkin Avenue (Ifeoma Ebo)

The presence of vacant lots in the community and on the Boulevard limits the impact that residents can have in the transformation of their community. There is no distinction between the treatment of land around the NYCHA developments and the underutilized or vacant lots in the community. This is troubling seeing that most of Mother Gaston Boulevard is lined with public housing on either side, creating an experience of walking through vacant land with no active street life. Lewis feels that due to limited local ownership and significant public land along Mother Gaston Boulevard, resulting in “too much authority given to the police over public space.” Residents are robbed of the opportunity to participate in the act of public safety and making decisions on how technology is used to address the nature of crime in their community.

Technology and public safety on the street

In response to street violence, the NYPD created CompStat, an online data-driven police accountability and management tool that geographically maps crime based on its closest proximity to street intersections. CompStat, uses technology that relies on just three historical variables to make its predictions: type of crime, place of crime, and time of day. This information can also be valuable in the process of street design to encourage solutions that further assist in reducing the unique type of crime based on geographic location.

NYPD CompStat Platform

In partnership with the NYPD and NYCHA, the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice took CompStat to another level by creating NeighborhoodStat – a data-driven participatory problem solving structure bringing together city government and residents to problem-solve public safety issues specific to each development. This initiative includes reviewing data and tracking outcomes to ensure that the City and its residents are able to evaluate progress in real time and deliver results. Amy Sananman, Executive Director of the Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety stressed the importance of the participatory process, “It’s important for law enforcement to build a relationship and a rapport with people in the community in order to create change.” Through the collaborative use of community crime data, the sense of ownership over addressing crime on public streets becomes a shared responsibility between residents and their local law enforcement.

“You can have police presence without having police violence.”

— Amy Sananman

Aside from the advancement of the physical construction of streets, technology has also advanced the ability of the public to be involved in the design, development and control of activity on public streets. One of the major challenges to addressing perceptions of justice along Mother Gaston Boulevard is the fact that there are numerous public assets along the street that do not work collaboratively to provide a unified identity for this central corridor. This challenge also presents an opportunity for various city agencies to work together to create a street presence that is not dominated by underutilized land, but encourages the public to engage with the street in new ways. The use of technology can advance this agenda in the use of tools to encourage meaningful social interaction, information exchange and accessibility of government processes.