Editor’s Note: The Forum for Urban Design is embarking on a campaign to collect ideas for compelling projects, plans, and policies to better New York City under the next mayor’s tenure. To tie in with this theme, the Urban Design Review will be featuring lessons from pioneering global cities. To start things off, William H. Fain, Jr. has written about Los Angeles’s transition from car-centric sprawl to pioneering urban laboratory in Urbane Renewal.

Los Angeles has new lessons to offer urban living today. And despite its sprawling and suburban reputation, its brand of urbanism may be influencing cities around the world as much as its older, Eastern US counterparts.

Founded in 1781 as a tiny pueblo of 48 souls, the city’s first generation of significant urban growth occurred in the late 1800’s through the early 1900s as small towns emerged in the region centered around a booming LA downtown. Early development was modest compared to Eastern, well-established cities of the time, but the surrounding small towns and downtown were connected by an 1,100 mile streetcar system—much in the manner of Boston, with its “streetcar suburbs”. This first generation of development established an urban footprint for the region, structured with a public transit system and street grid, which provide the building blocks for the redevelopment and densification occurring today.

Boosterism began in the 1890s, beckoning easterners to head west to the healthy, sunny southland. This first generation city extended well into the 1920s coinciding with the formation of major industries in oil production, movies, finance and aeronautics. The city’s expansion was catalyzed by many new educational institutions, including UCLA, Occidental, the Claremont colleges and Caltech. LA is second in the world only to New York City in number of institutions of higher education, which bodes well for its future, competing in the world arena of information and knowledge.

Opening day of the Pacific Electric Line at the Long Beach Pier, ca. 1900-1902

Digitally reproduced by the USC Digital Library; From the California Historical Society Collection at the University of Southern California

The late 50s and early 60s was a robust time of regional transformation. Southern California epitomized an informal lifestyle and a spatial freedom unparalleled in New York and the East Coast. LA was a perfect setting for the automobile boom following WWII. Wide open spaces between the small towns and the downtown filled in with tract housing for vets home from the Pacific campaign. The car and the single-family home with backyard, pool, and barbecue prevailed. Artists were also seduced by the open urban landscape and informal lifestyle. At a UCLA presentation in 2000, David Hockney recalled the freedom he felt “returning to Los Angeles from London, arriving at my hillside residence and setting out at sunset in a convertible, driving along Mulholland Drive toward Malibu.”

The automobile was viewed as an extension of one’s living space and personal freedom. In the 60s and subsequently, developments like Century City were laid out around automobile access and parking dimensions. Developments like Irvine looked vastly different from the super grid areas of the region established earlier. Older places in the region like downtown Los Angeles were characterized as outmoded, congested, and consequently abandoned for these new car-oriented environments.

Old Pacific Electric cars are piled up like toys at junkyard on Terminal Island, awaiting dismantling to become scrap metal.

Originally published on March 19, 1956 in the Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles Times photographic archive, UCLA Library)

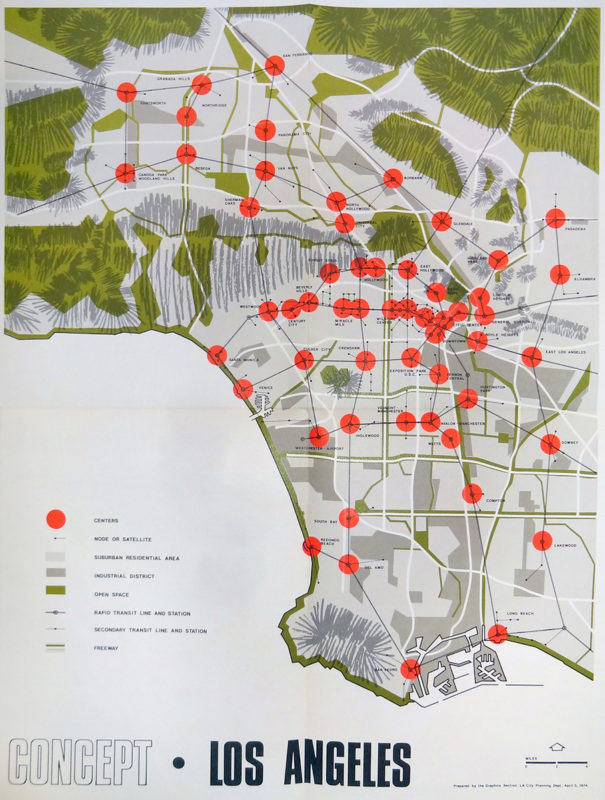

When the freeway system took hold in the 60s, it truly redefined the region. Calvin Hamilton, the Los Angeles planning director, introduced the “Centers Concept” in the 60s, which acknowledged the polycentric nature of the area. Los Angeles became one of the first metropolises developed around this new pattern.

Others have modeled their growth after LA–especially urban regions with high car dependency, like Houston and Phoenix. LA has also seduced the world with its informal life style and its attitude of integrating work and leisure. Although LA typifies what has happened and what might happen in many other US cities, one thing is certain: LA is building a new form. Los Angeles transformations continue, both planned and unplanned. Our tastes and preferences are becoming more urban: even the culture of the car is being challenged.

In 2008, Angelenos passed a sales tax to build new transit lines; we seemed to understand—finally—that we need an alternative to the car. Some undoubtedly supported the measure in the hope that transit use by others would free up the roads. And while opponents narrowly defeated the extension this year, a new culture around public transit is emerging. Little by little, the city is beginning to recognize that older residential, commercial, and industrial neighborhoods are assets for resettlement, and–recalling the old Red Car system–require a vastly improved transit system that is more efficient, faster, and with greater capacity. Already, HOV lanes are being expanded; one stretch of the 110 is now also a toll lane, with more slated to follow, including several miles of Interstate 10 east of downtown.

Along with transit, attitudes about density are changing, too. Wilshire Boulevard of the 30s was envisioned as the city’s “main street” even though it passed through multiple jurisdictions on its way from downtown to the ocean. Some imagined Wilshire could become Los Angeles’s Park Avenue or 5th Avenue. Today in the Wilshire corridor and downtown, residential and mixed-use projects are being built on commercial and industrial parcels that allow high-density housing and are increasingly transit-related. This intensification is also reasonably popular, as most of these developments do not directly impact existing residential neighborhoods.

The key to all of this is that there is pent-up demand for multi-family apartments and condos with street-level retail in walkable settings, fueled in part by the urban experience of new generations of immigrants. As perhaps envisioned by planner Hamilton, incremental development has actually happened consistently over time, forming a series of dense urban “nodes” with names known to all, like Santa Monica, Beverly Hills and of course, Hollywood.

These urban centers have recently been mapped by Samuel Krueger in a USC graduate student thesis in geography. He concludes that our “centers” are becoming similar to the mix of uses found in Manhattan or the Loop, but in Los Angeles they are much larger geographically and accessible by car, bus and in part, by subway—an example of LA’s unique urbanism. In this view, the city’s “core” now extends from east of downtown to the Pacific, and is now rich in business, religious and cultural amenities as well as a broadened mix of residential options.

The Centers Concept, 1974

Courtesy of recode.la, Download the PDF

Small, incremental development seems to be the hallmark of Los Angeles. One might almost say that we have a disdain for bigness, quite a contrast from New York City. And while LA lost much of its corporate infrastructure through the 80s and 90s, the city has continued to grow and thrive. Mayor Villaraigosa recently stated that 70 percent of Angelenos are employed by small businesses. Small business is the DNA of the city.

Outdoor living is naturally part of our make-up. However, the majority of open space in the city is private with few public parks or strategically placed public plazas for citizens to meet and socialize. When Paul Goldberger arrived here from NYC in the mid 1980s, he remarked to architect Tim Vreeland how private the city seemed. Statistically, we are among the most public open space-deprived cities of the US; we never experienced the “City Beautiful Movement” and other civic initiatives of eastern cities in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Consequently, the quantity and quality of public open space suffered. We need to develop many more and various parks and plazas, gathering places to celebrate our civic and ethnic diversity–for socializing, chance encounters and impromptu business meetings required by the new information economy.

As a “creative” place, Los Angeles is very different today than its 1960s self. At the same UCLA conference in 2000 where Hockney made his remarks, aggressive questioning from a youthful audience portended the future: what about the open space of the inner city and in older neighborhoods? Students questioned the so-called “freedom” and inventiveness these places offered the artist. Instead, they cited engagement with the city as creative stimulus, as opposed to his reminiscence of “getting away from it all” in his convertible in the Santa Monica mountains.

Still, Los Angeles is second only to New York in population and is the major city of California–the world’s seventh largest economy. There are over 200 languages spoken in Los Angeles and our schools teach in more than 40 languages. LA remains a “creative island,” building on its traditional assets while embracing the new complexities of ethnic diversity, knowledge infrastructure, multi-faceted public transit and urban densification, crafting a new Los Angeles urbanism.

William H Fain, Jr., FAIA is an architect and urban designer. He is the managing partner and directs master planning and urban design for Johnson Fain, a firm of 50 architects, planners and interior designers, headquartered in downtown Los Angeles. His projects have won several national AIA and Progressive Architecture awards including Mission Bay in San Francisco, Beijing’s new Central Business District, the Greenways Plan for Los Angeles and the American Indian Cultural Center in Oklahoma.

Image Credit: (1) Cover Image. Eastbound Wilshire Blvd (2008). Source:Flickr/Atwater Village Newbie. (2) A Mountain of Red Cars. Source: Los Angeles Times Archives/UCLA. (3) Los Angeles Centers Concept. Source: Planetizen/Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority.