The Urban Design Forum’s 2018 Forefront Fellowship, Shelter for All, addressed the homelessness crisis in New York City by examining how to dignify the shelter system through better design and exploring the root causes of homelessness and housing precarity. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on how to address the prison-to-shelter pipeline, public bathrooms, public realm management, supportive housing, and racist housing policies, which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

Read the full compilation of Shelter for All proposals and interviews here.

By Julie Chou, Kevin A. Gurley and Boyeong Hong

In a city as large, dense and diverse as New York, there is a need for accessible, clean and safe public bathrooms. Like housing, public bathrooms are a basic need, public health concern, human rights concern, and quality of life concern. We propose a series of creative legislative, funding and management strategies for the City of New York to create more public bathrooms.

Public bathrooms are an integral part of the public realm. The public realm is publicly accessible space such as streets, squares, parks and open spaces. As these areas support and facilitate urban dynamics, social interaction, and public life, the public realm plays a significant role in the health and livability of the city. Amenities in the public realm, like playgrounds and drinking fountains, are resources offered to the general public for their use and enjoyment. Considerations of public amenities have focused predominantly on recreational amenities or aesthetic amenities, like street furniture and information kiosks. Bathrooms, which are vital to engaging in the public realm, are often forgotten and contentious.

Historical Background

Historically, “public” bathrooms referred to restrooms created in noncommercial public spaces for people who did not yet have a toilet in their home.1 One of the earliest public bathrooms in the United States was one built in Astor Place in New York City in 1869.2 It would be one of the first in a fast-growing, immigrant city where access to a toilet in residences was considered a luxury.

By the 1930s, with Robert Moses as the Parks Commissioner, the city increased the number of public bathrooms, and also built up an impressive network of public pools and showers for public usage. In 1934 alone, the administration renovated 145 city comfort stations.3 Many of these facilities, such as the public pools and showers at city beaches, are still open and enjoyed by many New Yorkers and visitors. However, in the decades following World War II, particularly in the 1970s through the 1990s, many of the public bathrooms were closed.

The 1970-1980s were a particularly challenging time for the City of New York as it faced significant budget shortfalls. After narrowly avoiding bankruptcy in the 1970s, the city was required to make harsh budget cuts. Public bathrooms were shuttered. While many public bathrooms suffered from these budget cuts, an increase in crime, vandalism, sexual activity, and drug use exacerbated their closing.4 As maintenance costs increased and public perception waned, public bathrooms were no longer desired amenities for investment by the City.

The responsibility of maintaining public bathrooms fell increasingly on local businesses and property owners. In the 1980s, the city’s Department of City Planning began the Privately Owned Public (POPS) program that offered real estate developers bonus floor area or waivers in exchange for providing and maintaining public bathrooms in their public spaces. Around 14 public bathrooms were created during this time.

Despite growth in the city’s population, economy, and tourism, public bathroom conditions have changed very little.

In 1990, a group of homeless people sued the City of New York and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority for lack of access to public bathrooms. The lawsuit brought to light the persecution, shame, and physical pain that homeless people experienced for not being able to find a bathroom to urinate or defecate.5 As a result, the city formed the Public Toilets Working Group a year later, and in 1992, six sidewalk toilets from Europe were installed in Manhattan with approval by Mayor Dinkins for a four month test period. Monitored by attendants, they were used over 40,000 times and were considered a success. The City was planning to order 100 toilets and install them aross the five boroughs by 1994.6 However, complications from the City’s extensive land use review, pushback from accessibility advocates, and sorting out the contract with one bidder stalled the deal for years. It was not until 2006, under Mayor Bloomberg that a deal was made that included 20 automated public toilets (APTs) in a massive $1.4 billion dollar street furniture contract.7 To date, only five of these toilets have been installed.

The availability of public bathrooms has not increased significantly since the 1970s crisis. We believe the city has not truly recovered from this era, both in stigma around public bathrooms, but also in rebuilding the large network of public bathrooms it once had. Despite growth in the city’s population, economy, and tourism, public bathroom conditions have changed very little.

The Need for Public Bathrooms

Public Bathrooms Are Essential to a Dignified Public Realm for All, Especially Those Living on the Street

Picture the Homeless (PTH), a local nonprofit in New York City, started their civil rights campaign “Free to Pee” in 2018 to advocate for safe clean public bathrooms on the streets. They noted the following: “This is not just a homeless issue…this is a New Yorker issue. This is a tourist issue. This is a women’s issue. This is an everybody that’s gotta pee issue.” They also noted, “For homeless people, a little thing like needing to go to the bathroom can cause big problems. Buying a four dollar coffee to use a bathroom in a cafe is not always an option. Many homeless people have had medical emergencies or police interactions as a result. Homeless people experience urinary tract issues and related health problems at a rate 300% higher than the general population, and many suffer from extreme dehydration because they never drink water to minimize trips to the bathroom.”8 Even though we need a bathroom as a basic need and have a right to use one, refusing people bathroom access remains a remarkably effective form of social exclusion.9

The State of Public Bathrooms in New York City

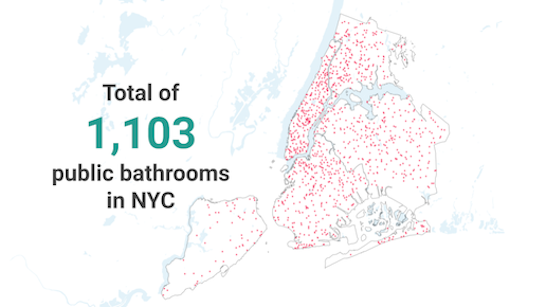

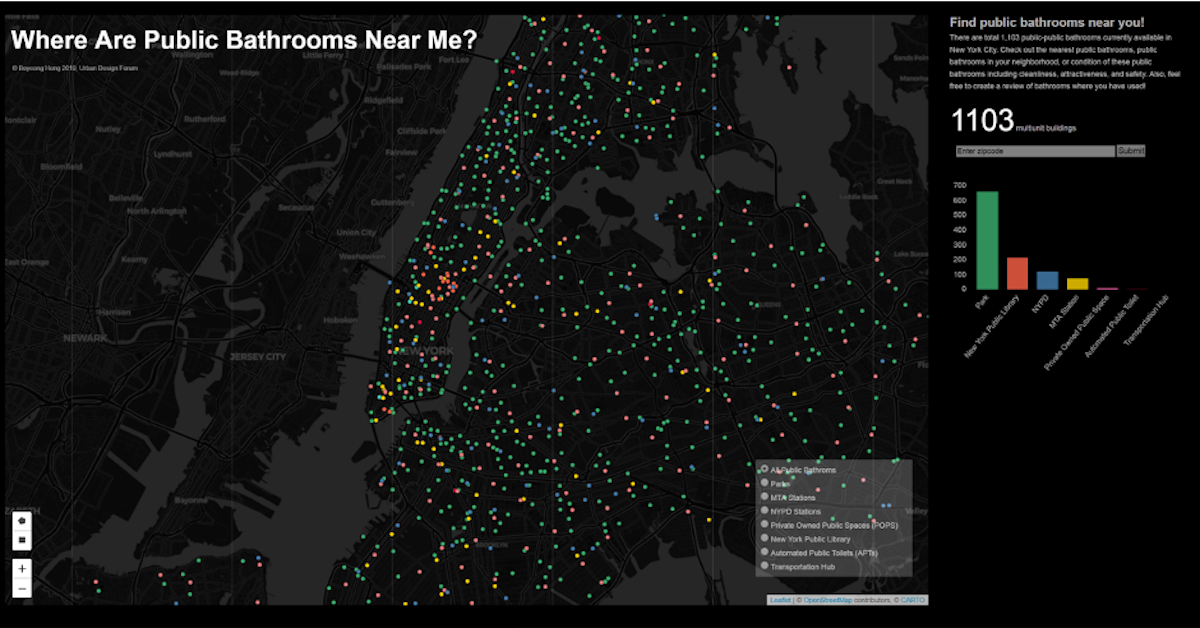

We looked at the number of existing public bathrooms in NYC and found that there are around 1,100 public bathrooms spread out among the five boroughs in various public spaces. There are 662 bathrooms in our 1,700 public parks, 78 bathrooms in our 468 subway stations, 4 transportation hubs with public bathrooms in Manhattan, 216 bathrooms in the public library system, 125 bathrooms in police stations, 5 automated public toilets in our plazas and on our sidewalks and 14 public bathrooms in the 550 Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS).

We then investigated what is an adequate number of bathrooms for different public spaces. The Uniform Plumbing Code requires 1 toilet for every 500 persons in large assemblies. The United Nations standard for refugee camps is to provide 1 toilet for every 20 people, a standard that has been used by city officials in Los Angeles and Seattle in regard to the lack of bathrooms for people living on the streets.10 Yet, for a city of about 8.4 million people, 1,100 bathrooms is only 1 bathroom for every 7,700 New Yorkers, well short of the standards we demand elsewhere.

New York City ranks a dismal 80 out of the top 100 cities in the United States in the number of bathrooms that we have in our parks to our total population.11 We provide 0.8 comfort stations per 10,000 residents whereas Chicago, San Francisco and Washington DC all provide three times more than New York City.

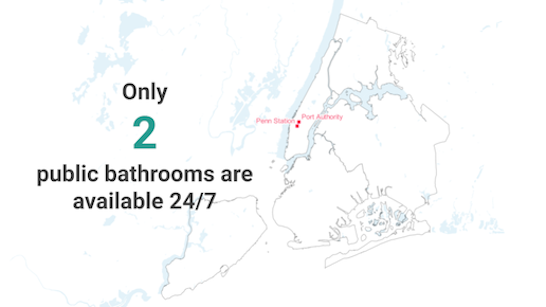

For people experiencing homelessness, other sites do exist for bathroom access. Currently, the city has a total of five drop-in centers with access to bathrooms and showers for the homeless. Yet, only two of them are open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Besides these centers, the only public bathrooms open 24/7 are in Penn Station and the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan. With more than 3,675 people living on the street, we are well short of providing the 183 toilets required to meet the standards for other cities and spaces. However, this number would be higher if we consider the number of homeless people in that “in-between” stage outside during the day waiting for shelters to open.

Why is it so difficult for the city to provide more public bathrooms? Costs, siting, the extensive approval process and community pushback are some of the challenges. The comfort stations built by the Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) cost on average $2,000 to $5,000 per square foot. With recent reports that comfort stations are running up to $6 million each, DPR is currently considering more cost-effective ways to provide bathrooms including automated public toilets, stand-alone toilets that are not conditioned, and bathrooms in trailers. The comfort stations also require the approval of five different external agencies. DPR is currently working to streamline this process.12

Not only are there challenges to providing an adequate number of bathrooms but keeping them clean and well-maintained has been a challenge for the City. The Legal Action Center reported in their 1990 lawsuit, “that of the Transit Authority’s 105 busiest restrooms, fewer than a third were open to the public, and half of those were in bad condition. A survey of 526 [comfort] stations in the city’s 1,540 parks found that nearly three-quarters were ‘either closed, filthy, foul-smelling or without toilet paper and soap’.” In 2019, Comptroller Scott Stringer published a study on existing comfort stations and reported that “among the 1,428 NYC Parks bathrooms, nearly 400 sinks, toilets, walls, ceilings, changing tables, and other features were damaged or missing during their latest inspection. Over 50 “hazards” were identified that presented the chance of moderate to debilitating injury.” The MTA’s significant budget deficit and DPR’s limited budget suggest that we need radical new ideas to overhaul the existing conditions and provide proper maintenance for these public bathrooms.

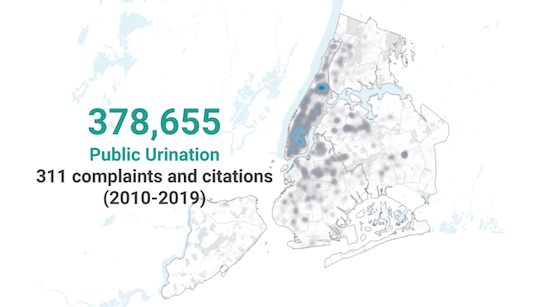

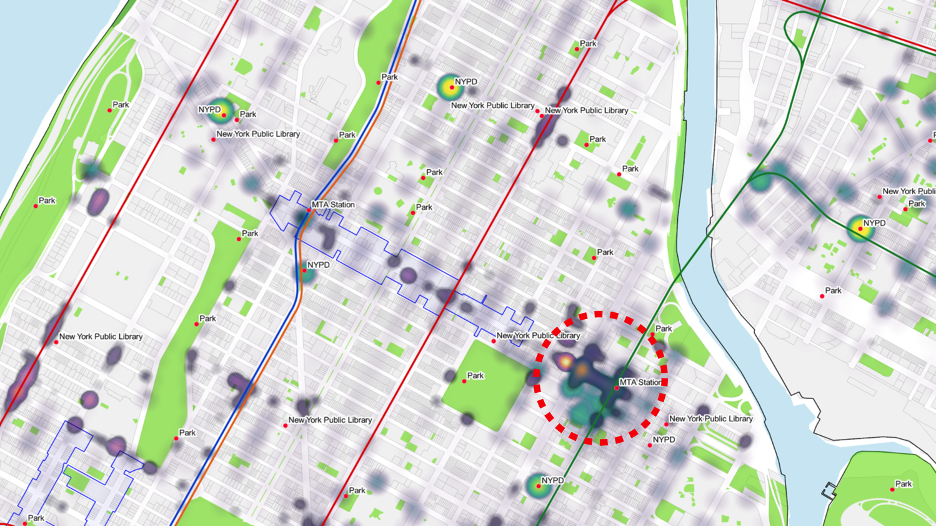

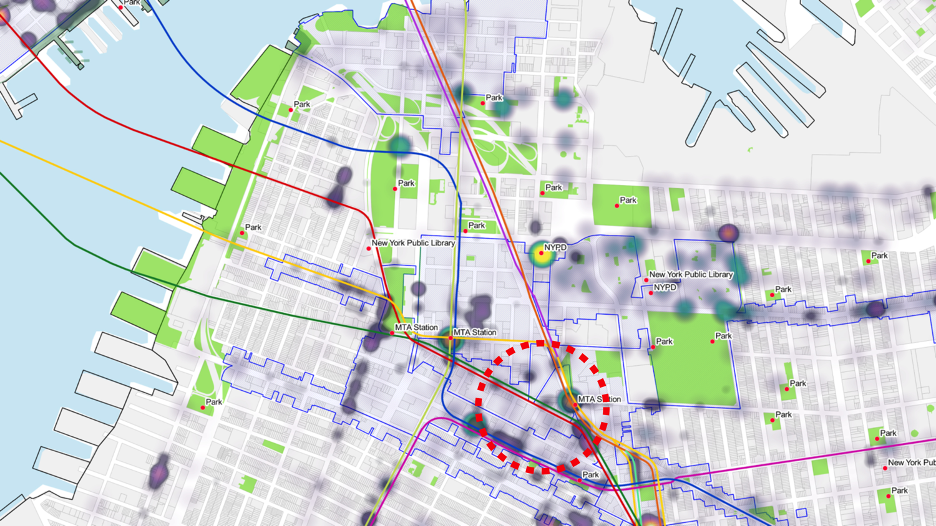

The lack of proper public bathrooms goes hand in hand with the amount of public urination in the city. Before the Criminal Justice Reform Act in 2017, the City issued an average of 20,000 public urination citations per year. We have mapped out areas of the 311 complaints on public urination and suggest that the City look into installing more public bathrooms in these “high priority” areas.

Precedents

The need for public bathrooms has been addressed in many American and international cities. The following are a few examples that New York can learn from.

United Kingdom: In London, the city has a program called the Community Toilet Scheme that supplements their public bathrooms by paying retailers an annual stipend to open up their bathrooms to the public. The images are example of the sign that retailers would provide in their storefronts and the sign that the city would provide directing people to the nearest public bathroom. London, which is most similar to New York City in the UK, has 75 businesses participating in their city and each receives 600 pounds a month. The businesses are required to be near high pedestrian foot traffic and are monitored once a month by the government.14 There are similar programs in Germany, Switzerland and Australia.

Portland, Oregon: The City of Portland, Oregon developed their Portland Loo with the concerns about safety and maintenance in mind. These 24/7 public bathrooms can be purchased for $90,000 to $150,000. The cost of utility connection in the sidewalk varies with different cities. They have open slats that allow the units to be cleaned easily and are composed of materials that resist vandalism. Because these units are not automated, they have less chance of breaking down and requiring repairs. There have been 50 Portland Loos installed in over 12 cities in the US and Canada so far.15

Washington, D.C.: In 2018, Washington DC passed a bill called the Public Bathroom Facilities Installation and Promotion Act. The two-prong act will install stand-alone toilets on city sidewalks as well as compensate retailers for opening up their bathrooms similar to the London scheme. The bill proposes the installation of two 24/7 sidewalk toilets similar to the Portland Loo. There would be a task force to identity possible sites. The city will also identify two Business Improvement District (BIDs) to pilot a public access incentive, which will likely amount to between $1,500 and $2,000 per year for retail, restaurants and bars that participate.16

Singapore: In Singapore, the former Minister of the Environment created the Happy Toilet Program (HTP) where retailers have the option of getting their bathrooms rated and put on an online map. The public bathrooms are rated on Design, Cleanliness, Effectiveness, Maintenance and User Satisfaction. Singapore has one of the cleanest public bathroom systems in the world. The program provides jobs for the elderly and housewives, who are the predominant group of raters. Having a rating program promotes both accountability and bathroom standards for both bathroom users and providers.17

Bryant Park, New York: In New York, the Bryant Park bathrooms are a successful precedent for public bathrooms privately funded by the Bryant Park Corporation. The bathrooms were renovated for significantly less than the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation comfort station bathrooms at less than $900/sf. The Bryant Park bathroom features Toto fixtures, a coffered ceiling, crown moldings, and new imported tiling. The BID spends $271,000 annually on maintenance to create a luxury bathroom for all to use. The bathroom has full-time attendants who keep the bathroom clean. It is clad in luxurious stone material and displays fresh cut flowers daily along with classical music. It attracts over 3,200 people a day and over a million people a year and shows that beautiful, well maintained public bathrooms are not only a need but an attraction.18

Herald Square, New York: One of the major BIDs in the city preferred manual toilets with attendants over automated toilets. The 34th Street Partnership installed automated public toilets in 2001 in Herald and Greeley Squares and subsequently closed them in 2008. They had 28,000 visits the first year to fewer than half that in 2007. They replaced the APTs with bathrooms with full-time attendants and stated, “bathrooms with attendants cost no more to maintain than the automated ones,” and “when people see them, they know the bathrooms are clean.”19

Automated Public Toilets (APTs): There are five Automatic Public Toilets (APTs) installed in Department of Transportation (DOT) plazas or adjacent to parks in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens. These bathrooms are self-cleaning and fully accessible. In 2006, DOT signed a deal with Spanish advertising company Cemusa in which the company pays the city $1.4 billion and fabricates, installs and maintains 3,500 bus-stop shelters, 330 newsstands and 20 APTs in exchange for advertising rights for a period of 20 years.20 Though all the promised bus stops and newsstand have been installed, 15 APTs remain in storage. The challenges of installing these bathrooms include difficulty accessing utility connections, pushback from local community groups, and the Public Design Commission’s approval process. Meanwhile, the costly installation and maintenance of APTs, compared to bus stops and newsstands, provides less incentive for Cemusa to move forward with setting them up.

APTs cost 25 cents for 15 minutes of privacy, after which the doors pop open (a warning light and alarm go off when there are only three minutes left). An automatic arm sprays water and disinfectant over the public awareness and regular maintenance impairs the full success of APTs, a robust network of these facilities installed across the city could present an immense opportunity for increasing access to public bathrooms. To date, the Madison Square Park APT averages 50 users a day and the Grand Army Plaza APT serves an average of 18 people a day.21

Times Square Subway Station, New York: The Times Square subway station also provides popular public bathrooms in New York. It was built in 2004 by Boston Properties, the developer of the Times Square Tower, who also renovated the entrance to the subway station in a deal with the MTA. As part of the agreement, Boston Properties pays Times Square Alliance, a local BID, $100,000/year to provide full time attendants who monitor and maintain the bathrooms. Attendants were requested by local businesses and the transit authority during the approval process for this deal.22

Establish a Public Bathroom Design Standard

We believe the public sector needs an excellent standard for public restroom design. In our recommendations, we focus on Cost Effectiveness, Safety, Design and Ease of Maintenance.

For Cost Effectiveness, limits to the City budget require creative financing solutions to open more public bathrooms. Several countries have developed programs to incentive retailers to open up bathrooms and make it free to pee for the public. We suggest New York City organize a similar program that would encourage private retailers to be part of this solution and provide a public good for this city. We believe developers could create and staff public restrooms in return for development bonuses, similar to how the city rewards transit improvements or landmarks investments. We can also continue to generate revenue from advertisement. Finally, we can create a volunteer-run public bathroom association.

Safety is a huge concern, as drug use is one of the reasons why bathrooms have been shut down over the years. Our recommendations include installing bathrooms at areas with high pedestrian traffic, installing advanced security cameras outside of public bathrooms with two-way communication devices that check in with the occupant every 5 minutes, installing an anti-motion detector that alerts the attendant if the person in the bathroom is motionless for a certain period of time, installing a buzzer to be let in, providing full time attendants trained in administering naxolone, and installing blue lights so people cannot locate their veins for drug use.

When it comes to Design, public bathrooms should be welcoming. They can display art created by the local community, offer attractive signage, and be built with beautiful, long lasting and durable materials. A public bathroom design competition can help to elevate the design of our public bathrooms in the city, make public bathrooms an attraction similar to the Bryant Park bathrooms, innovate best practices for public bathrooms and educate people on the importance of public bathrooms.

For Ease of Maintenance, stainless steel finishes are more resilient and easier to clean. There are dispensers that are embedded with sensors to track and predict refills for paper towels and soap. In Asia, there are dispensers with cleaning agents to allow users to wipe the toilet before and after use. Providing two-way communication devices can also allow people to call in and report a clogged toilet or a broken fixture. There are also hygiene monitors that measure cleaning frequency as well as allow customers to push a button to rate the cleanliness of the bathroom. This can help better maintain the cleanliness of the bathroom and ensure they remain attractive and clean for users.

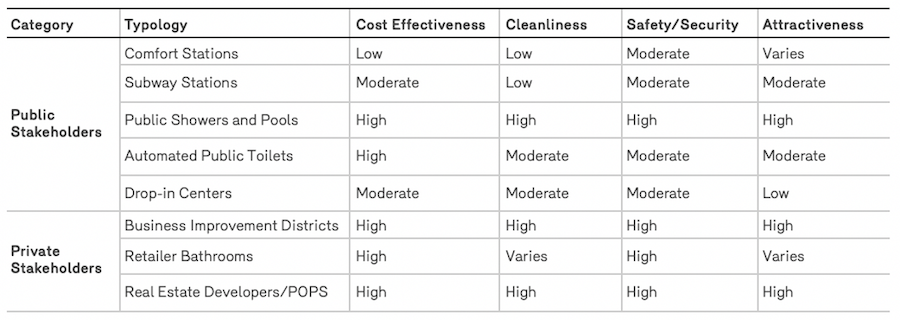

We studied eight different public bathroom typologies in New York City. The chart below rates each typology on their current conditions in terms of the four categories that we described above. Comfort stations are currently very expensive, in poor shape in terms and maintenance and often vandalized. Some of the new comfort stations, albeit very expensive, are designed by architects selected by the NYC Department of Design and Construction and have won design awards and are attractive to users. This typology will require creative thinking and a lot more funding to make it a well-functioning system.

In addition, real estate developers are providing attractive bathrooms in their privately-owned public spaces. The developers are awarded extra development rights to provide this amenity so it is cost-effective for all parties. These spaces are designed by reputable architects and spaces are kept clean and safe as the developers have more resources and greater interest in keeping their building well-maintained.

Crowdsource the User Experience and Needs

Every citizen can be the eyes of the city as they monitor, evaluate, and patrol the city’s public bathrooms. In order to promote citizen stewardship, we are currently building an interactive web visualization platform of public bathrooms. Similar to Yelp, our platform is designed and built for the general public. Any user can search for nearby public bathrooms; provide information such as the number of stalls, operation hours, and specific address; and offer ratings and reviews.

Participation promotes cleaner and safer public bathrooms through public reviews and feedback. Additionally, this platform would be used as an indirect assessment tool for public bathroom management by city agencies and organizations.

In addition, the general public can evaluate and vote on potential “high-priority” sites through the public web interactive platform. They can raise their voice by labeling “request” stickers on locations where they want to have additional bathrooms in the interactive map to support a public bathroom system in their neighborhood. The “request” sticker function can also be connected to NYC 311 system, the centralized platform for non-emergency city service requests.

Demand a Legislative Response

We need public citizens, along with advocacy groups, city agencies and the private sector to work together so that access to public bathrooms is a right and not a scarcity.

We propose the following resolution, which could be adopted by City Council demanding action to create access to quality, clean and safe public restrooms:

- Create an interagency effort between the New York City Department of City Planning, the New York City Department of Mental Health and Hygiene, and the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services to determine an adequate number of public bathrooms that meets NYC public health needs.

- Mandate the NYC Department of Transportation to work with community groups to install the remaining 15 APTs within two years. We also ask that DOT make these toilets available 24/7.

- Encourage the NYC Department of Transportation to include sidewalk bathrooms in new plazas under the Plaza Program. To date DOT has created 69 new plazas through their Plaza Program and three of them have included APTs.

- Provide at least six full time employees at Parks where there is a comfort station so that bathrooms are safe and well maintained.

- Study how the NYC Department of Small Business Service can work with BIDs to create an incentive program for retailers to provide public bathrooms similar to UK’s Community Toilet Scheme.

- Amend the NYC Department of City Planning zoning text so developers providing indoor POPS over 10,000 SF or receiving the transit bonus are required to provide public bathrooms as an amenity. The current zoning text requires food kiosks for POPS larger than 10,000 SF. It would therefore make sense to add a public bathroom requirement for POPS this size as these amenities go hand in hand.

- Study how NYC Department of City Planning can amend the zoning text to provide an incentive for developers to get extra bonus FAR if they choose to provide and maintain a bathroom.

Test Cases

We took a look at three areas in the city where there is a high concentration of 311 calls regarding public urination and homelessness and lack of surrounding bathrooms to see if they would be viable locations for the 15 automatic public toilets left to be installed.

Midtown

There are many public urination reports in Midtown and the Times Square area, in part because of a large homeless population. It is also an area with the highest density of pedestrian traffic in the city and several sections of Broadway have been turned into DOT plazas to provide more open space for pedestrians and tourists.

In looking closer at how the plazas are being used and the street furniture in these crowded streets, we found three newsstands within view at the corner of 7th Avenue and 44th Street. We also observed a lot of street art, food stands, various types of seating in these public plazas.

Because public bathrooms are such an important amenity for open spaces to be accessible to people, it should be prioritized in the street furniture that occupies Times Square. We suggest the following options:

- Option #1: Replace one of the existing newsstands with an APT. Unlike the APTs, all 330 newstands have been installed by Cemusa. They generate significant revenue for Cemusa from their ads even though they have been selling less and less newspapers over the years.

- Option #2: Install an APT next to DOT plaza at 44th Street and Broadway away from entrances and projecting marquees.

Harlem

In Harlem, we noticed a particular concentration of public urination and homeless 311 reports at 125th Street between Lexington Avenue and Madison Avenue. The M35 bus drops people staying in shelters on Wards Island along 125th Street on a daily basis. In 2015, a local BID called Uptown Grand Central adopted the space under the 125th Street Metro North station as a NYC Department of Transportation pedestrian plaza.

The BID programs the space with activities for the community. Picture the Homeless is interested in saving and renovating the existing comfort station that was built in the late 1800s next to this DOT plaza. There are structural issues with the existing building that would be costly to repair. The BID is considering installing an APT there and demolishing the existing comfort station.

We believe there are two options for this area that is in desperate need of a public bathroom displayed.

- Option #1: Install an APT in this DOT plaza along the sidewalk between the two stairs to the platform above.

- Option #2: Declare the existing historic comfort station a landmark and repair it for service.

Downtown Brooklyn

In Downtown Brooklyn, there are several areas with high concentrations of public urination and homelessness 311 reports. The local community board in this district, suggested Columbus Park and Albee Square as locations for APT back in 2009. Columbus Park was rejected by the Public Design Commission as they thought the APT would clash with the Landmark buildings. Albee Square was being redesigned at the time and the Fulton Mall Improvement Association resisted, claiming there was not enough space for an APT.23 The DOT plaza was constructed in 2011. The square is surrounded by retail shops and at its peak time on weekends, up to 1,900 pedestrians pass this area per hour. The nearest public bathrooms are at the MTA station and park one to three blocks away.

We believe there is room to install an APT at Albee Square.

- Option #1: We propose locating an APT at the corner of DeKalb Avenue and Bond Street. This would site the APT along the path through the plaza to DeKalb Avenue. This location is set back from Fulton Street but still along the street so that there will be eyes on it for safety and security purposes. It may also be easier to connect to utility lines in the street at the periphery of the plaza.

- Option #2: We propose locating the APT along the east side of Century 21 between the existing benches and fire hydrant. This is a more remote location for the APT so that it is not in the way of pedestrian traffic.

Conclusion

New York City has a public bathroom crisis. There is a clear need for public bathrooms but our existing infrastructure is not meeting this need.

We call on the City to create a Public Bathroom Plan that would create quality public bathrooms to meet the need of all New Yorkers. We recommend that the mayor form an interagency effort to study and address the need of public bathrooms in a multi-prong effort using various public bathroom types.

We also call on our local representatives to fight for and protect our rights to public bathrooms so that all New Yorkers have access to clean and safe public bathrooms. Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) requires employers to provide their employees with bathroom facilities so that they will not suffer the adverse health effects that can result if bathrooms are not available. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, however, provides no such protection for the general public. We want to change this and want our legislative bodies to know that public bathrooms are a need, and not an option.

Authors

Julie Chou is a registered architect and Senior Associate at Magnusson Architecture and Planning where she is managing a variety of mixed-use affordable and supportive housing projects that help to address the needs of local communities and improve the wellbeing of their residents. She is a member of Manhattan’s Community Board 5 and sits on the Executive Committee, Land Use, Zoning and Housing Committee, and Budget, Education and City Services Committee. She holds a BA in Economics from the University of Chicago and a BArch from Cooper Union.

Kevin Gurley is a Principal Planner and project manager at MTA New York City Transit, Communications Co-Chair in the APA Latinos and Planning Division, and volunteer English instructor at Mixteca. He has experience in both the public and private sectors working on projects in cities in the US, Mexico, and China. He holds a Master in Urban Planning from Harvard University and a Master of Architecture from Florida International University in Miami.

Boyeong Hong is a Postdoctoral Associate and Research Scientist at NYU Marron Institute of Urban Management. Her research interests focus on how to apply urban informatics to real world problems in urban planning and operations by using big data analytics and urban computing. Boyeong holds a doctoral degree in Urban Informatics from NYU, a Master of City Planning degree from Seoul National University, and a BArch from Yonsei University.

Footnotes

1. Colker, Ruth. “Public Restrooms: Flipping the Default Rules.” Ohio St. LJ 78 (2017): 145.

2. Braverman, Irus. “Loo law: The public washroom as a hyper-regulated place.” Hastings Women’s LJ 20 (2009): 45.

3. Celia W. Dugger, “In New York, Few Public Toilets and Many Rules,” The New York Times, May 21, 1991, https://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/21/nyregion/in-new-york-few-public-toilets-and-many-rules.html.

4. Braverman 2009.

5. Felicia R. Lee, “The Homeless Sue for Toilets in New York,” The New York Times, November 1, 1990, https://www.nytimes.com/1990/11/01/nyregion/the-homeless-sue-for-toilets-in-new-york.html.

6. Steven Lee Myers, “Pay Toilets a Success, but They’re Still Closing,” The New York Times, October 30, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/10/30/nyregion/pay-toilets-a-success-but-they-re-still-closing.html.

7. Sewell Chan, “$1.4 Billion Deal for Bus-Stop Toilets Nears Approval,” The New York Times, May 12, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/12/nyregion/14-billion-deal-for-busstop-toilets-nears-approval.html.

8. Picture the Homeless Free to Pee Civil Rights Campaign, https://picturethehomeless.org/freetopee/.

9. Braverman 2009.

10. The Times Editorial Board, “L.A.’s streets have become a de facto toilet. We need more public restrooms,” The Los Angeles Times, July 13, 2017, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/editorials/la-ed-public-toilets-20170713-story.html.

11. “2019 City Park Facts,” The Trust for Public Land, https://www.tpl.org/2019-city-park-facts.

12. Yoav Gonen, “Parks Department May Shrink Costly Bathrooms to Save Cash,” The City, November 13, 2019, https://www.thecity.nyc/government/2019/11/13/21210700/parks-department-may-shrink-costly-bathrooms-to-save-cash.

13. Lee 1990.

14. “Community Toilet Scheme,” City of London, https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/services/transport-and-streets/clean-streets/Pages/Community-Toilet-Scheme-(CTS).aspx.

15. The Portland Loo, https://portlandloo.com/.

16. “Public Restroom Facilities Installation and Promotion Act of 2017,” The Council of the District of Columbia, https://pffcdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Bill-22-0223.pdf.

17. “Happy Toilet Programme,” Restroom Association (Singapore), https://www.toilet.org.sg/docs/HTPBrochure.pdf.

18. Rachel Sugar, “Bryant Park’s surprisingly refined public bathroom gets a $280k upgrade,” May 31, 2017, Curbed, https://www.toilet.org.sg/docs/HTPBrochure.pdf.

19. Andy Newman, “Flush-Forward Is Out. Hand-Scrubbed Is In,” December 10, 2009, The New York Times, https://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/12/10/flush-forward-is-out-hand-scrubbed-is-in/.

20. Jennifer Lee, “New Yorkers, You May Be Excused: A Pay Toilet Opens,” January 10, 2008, The New York Times, https://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/01/10/a-pay-toilet-opens-no-need-to-hold-everything/.

21. Sarina Trangle, “Finding a public toilet in NYC still difficult 10 year into program launch,” February 5, 2018, amny, https://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/01/10/a-pay-toilet-opens-no-need-to-hold-everything/.

22. Eddy Rámirez, “A Toilet Stop in Times Sq.? Just Ask to Be Buzzed In,” July 22, 2004, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/07/22/nyregion/a-toilet-stop-in-times-sq-just-ask-to-be-buzzed-in.html.

23. Simon Akam, “A Sidewalk Oasis, if You Can Find One,” August 30, 2009, The New York Times,, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/31/nyregion/31toilets.html.