The Urban Design Forum’s 2019 Forefront Fellowship, Turning the Heat, addressed ways how urban practitioners can advance climate justice principles across New York City. In partnership with the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, Fellows surveyed neighborhoods, studied buildings, interviewed local and international stakeholders, and produced creative research on mitigating heat. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on creating circular economic and sustainable models in NYC, developing community resiliency within NYCHA housing, factoring design into preventative care, and establishing a climate first approach to housing which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

Read interviews with Nadina Galle, Jennifer McDonnell, and Will Sibia to accompany this proposal, and view the full compilation of Turning the Heat proposals and interviews here.

By Lida Aljabar, Brandon Cappellari, Michael Izzo, Amy Macdonald, Rebecca Macklis, and Autumn Visconti

Introduction

Spurred by a culture of production, consumption and disposal, resources flow in and out of New York City in an exploitative and unsustainable linear model. A victim of its own success, the city now grapples with the effects of climate change it produces. The headlines are frightening: rising temperatures, vulnerable coasts, plastic oceans, and fragile food networks threaten our quality of life, with historically marginalized communities experiencing the greatest burdens. But the future does not have to be bleak. The path to a net-zero city is circularity, and New York City needs a system redesign. Circular urban models, which reuse and repurpose materials, food, energy, and water resources, have already been successfully adopted in cities and corporations around the globe. These profitable models demonstrate how a life-cycle and systems-view can reduce resource extraction, minimize harmful pollution, and create green jobs, while restoring environmental assets.

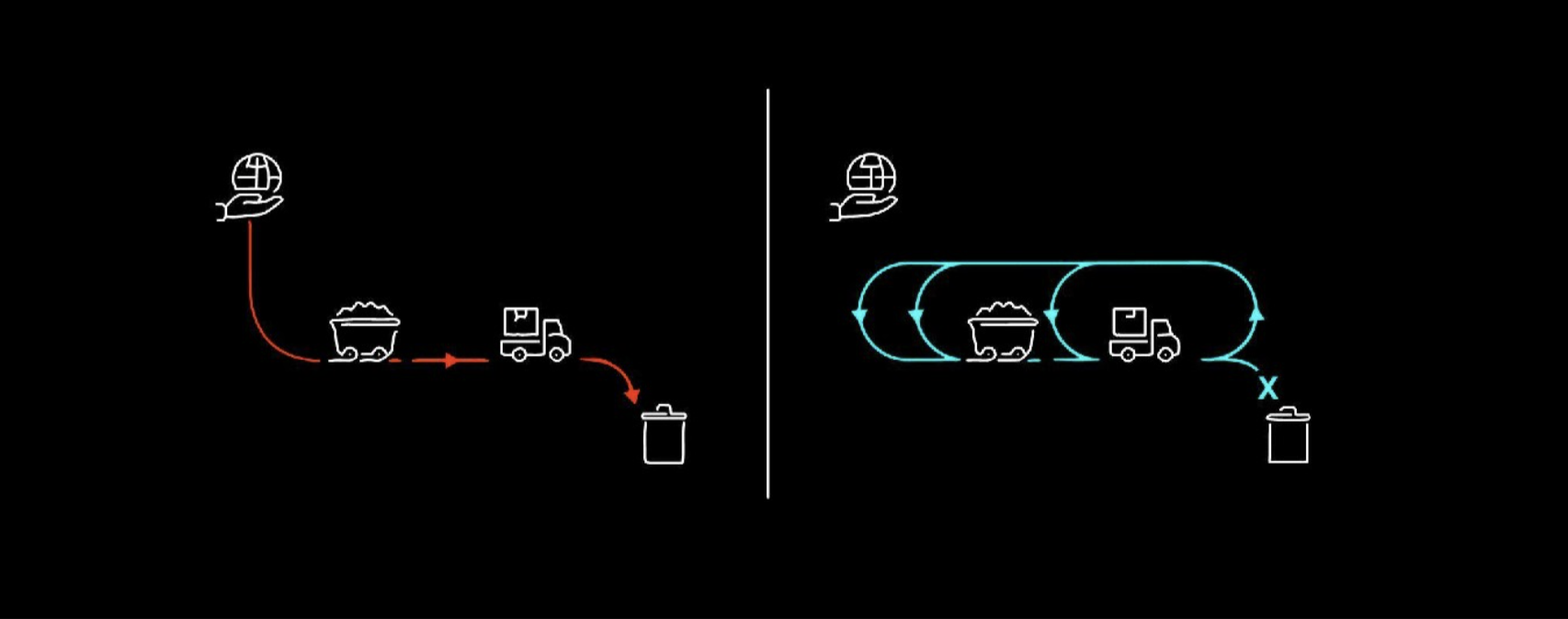

Our linear, leaky system

Today, our city operates in a very linear, very leaky system. Raw materials are extracted from finite resources, processed into a product, and then disposed of into our waste stream, often after a single use. This model reinforces an inequitable distribution of profits and burdens, with tremendous global impact. The constant extraction, processing, and waste produces a host of environmental and human injustices, resulting in the dramatic reshaping of our planet due to global climate change.

This linear economy pervades New York City’s most salient urban systems, including food, energy, and water. Our city systematically produces massive amounts of waste from these streams each day:

- 4,300 tons of food waste1

- 1.3 billion gallons water discharged into our oceans2

- 24,000 tons of trash (only 17% recycled)3

As a society, we have normalized the concepts of waste and constant resource extraction and production. At the same time, waste has disparate geographic impacts: for example, NYC has no landfills or incinerators, so that which is not recycled is discarded outside of city borders.4

Waste is the product of a design flaw and a culture in crisis. We are not experiencing a crisis of resources, but of how we think of and use them. We already have what we need.

An alternative: the circular economy

The circular economic model offers an alternative to this “take, make, waste” system. The circular economic model is regenerative and restorative by design, keeping resources in use at their highest value for as long as possible. This model builds upon three core principles: (i) design out waste and pollution (ii) keep products and materials in use for as long as possible and (iii) regenerate our natural systems to improve the environment.5

To tackle inequality, we cannot wait for growth to somehow bring equity and equilibrium; it has not done so in the past. To tackle pollution and our impact on the earth’s delicate balance, we cannot continue operating in our current linear economy. We must be disruptive by design. The circular economy requires a major mindset shift and could provide a pathway to prosperity for all, within the earth’s social and planetary boundaries.

Right here in New York City, 10% of electricity needs could be generated from food scraps, 78% of domestic water supply could be reduced through reuse, and we could implement a 60% increase in efficiency of electrical generation plants.

Moreover, the economic value of making a transition to circular economies is huge. Closing the loop would unlock an estimated $2 trillion in annual value in the U.S. alone6. In California, it is estimated that collecting, processing and manufacturing new materials from recycled waste streams generates thirteen times as many jobs as collecting and landfilling waste7.

Closing the loop on New York City’s urban systems

Creating lasting, systemic change toward a circular economy in New York City requires viewing the city both holistically as a set of interacting parts, as well as disentangling and analyzing the individual infrastructures, resources and processes within the city system. It requires constantly looking across scales, zooming in to a single element such as an apartment in a building, and zooming back out to larger scales, like that of a block and neighborhood.

Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture, Tarrytown, NY

Stone Barns is closing the loop on the food industry by practicing regenerative farming methods, conducting cutting-edge horticultural research, and providing training opportunities for farmers and culinary professionals alike.

GRID Alternatives

A non-profit based in California makes the most of a burgeoning green economy by connecting underserved communities to jobs and clean energy.

Hammarby Sjöstad, Stockholm, Sweden

Formerly an industrial site, Hammarby Sjostad is now a global model for zero-waste, energy net-positive and sustainable mixed-use development. Its defining feature is the interdisciplinary flows of energy, water and waste, resulting in a district which recovers 50% of its energy from waste, recycles 100% of its water usage and uses 80% of the energy recovered from waste within the district limits.

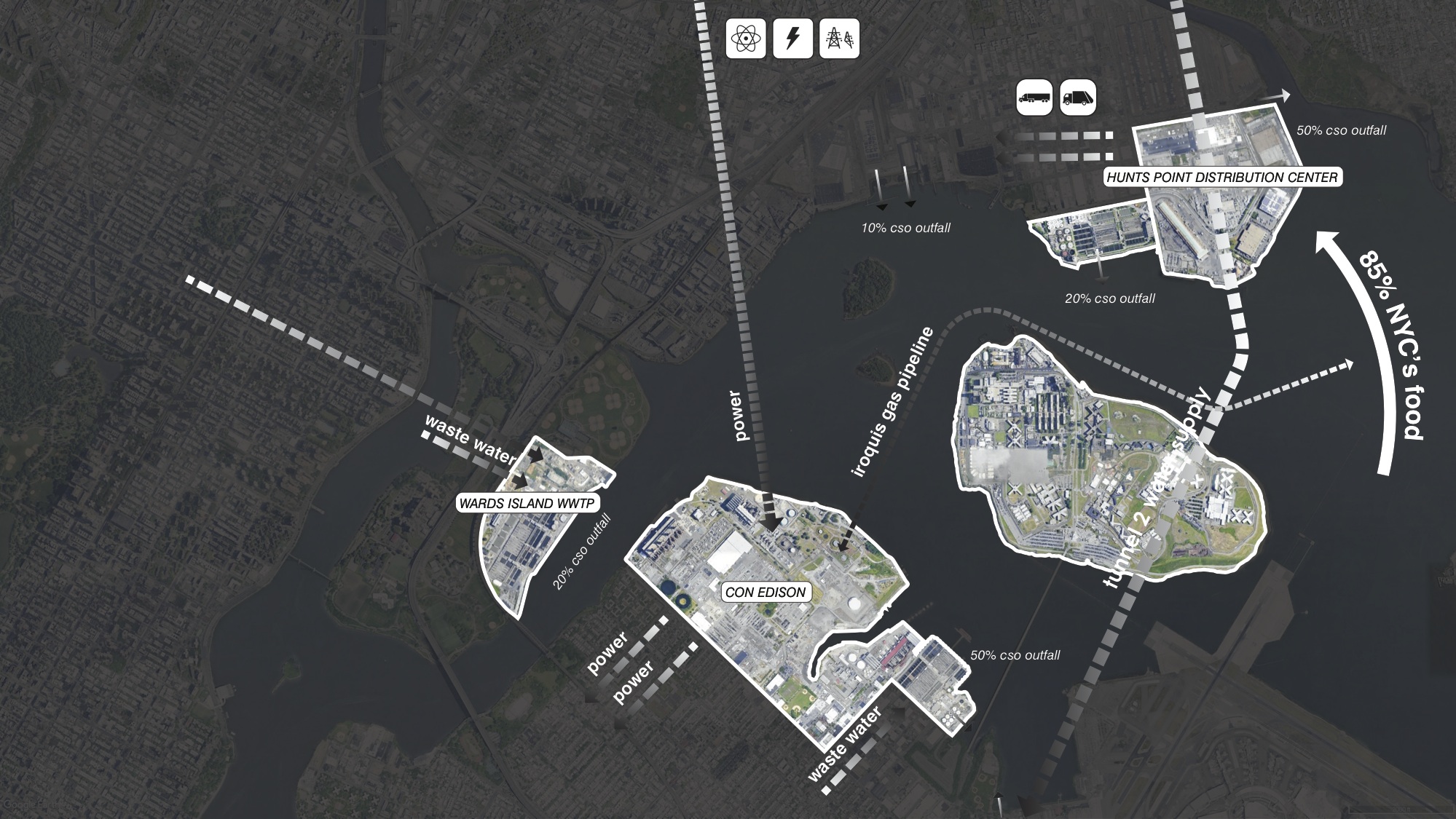

Inner Long Island Sound

For New York City, the Inner Long Island Sound is where we start. No place in New York City demonstrates the ill effects and missed opportunities of our wasteful linear model better than the Inner Long Island Sound. Spanning three boroughs, five islands and the waterways where the East River and its tributaries meet the Long Island Sound, the Inner Long Island Sound has for decades been the dumping ground for unwanted ‘leaks’ of the region’s urban systems. Multiple wastewater-treatment facilities, power plants, jails, noxious industries, combined sewer overflow, and waste-transfer stations are located within the area, highlighting the back- of-house mentality that has been taken towards this region for far too long.

Furthermore, the surrounding communities, which are among the lowest income in the city, suffer from the physical pollution and other industry externalities created by the systems at play. In the South Bronx alone, rates of asthma, poverty and unemployment are the worst in the city8. With the closing of Rikers Island Correctional Center, the City has an historic opportunity to close the loop on these siloed and polluting industries across the islands, water and banks of three New York City boroughs to restore ecologies and affected communities.

Through a history of disinvestment dating back to the 1600’s, the Inner Long Island Sound has been the collection point for a majority of the City’s waste and industrial streams. As a result, the region, including its predominantly low-income communities, bear the brunt of concentrated environmental consequences and risk.

Upon the arrival of Dutch and British settlers, the city’s marshy coastlines and ecologically rich waterways began to transform into more developed uses. At first, the islands and coastal areas of the Inner Long Island Sound remained either estates for wealthy landowners or uninhabited entirely until the industrialization era, when the city’s growth created a squeeze on space. A form of banishment, these islands became the systematic receiving grounds for people deemed unfit for the growing New York society. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the islands housed thousands of New Yorkers in quarantine, drug addiction treatment facilities, mental health institutions and eventually the thousands of daily inmates at the Rikers Island Correctional Facility. Even the bodies of poor and working-class people were relocated from Manhattan potters’ fields to the islands to make room for parks and squares.

The Inner Sound soon became both the collection and discharge point for large shares of New York City’s streams of resource and waste. In the early 1900s, the salt marshes of Hunts Point Peninsula were drained and filled, paving the way for the Hunts Point Food Distribution Center, followed by the construction of three wastewater treatment facilities, a power generation facility and La Guardia International Airport.

Superstorm Sandy exposed the risk of critical facilities in this low-lying coastal area to the effects of climate change, including sea level rise and coastal storms, as well as extreme heat and peak energy loads.

2. Inner Long Island Sound today

- Food

The Hunts Point food distribution center is a hub of the food supply for 22 million people in the Northeast U.S., housing produce, fish and meat markets. Its $5 billion annual economy provides over 20,000 jobs to the region9. 90% of the freight (at 3.3 billion pounds) is moved by truck, sending hundreds of trucks and their exhaust fumes through Bronx neighborhoods each day10. 46% of all food distributed through NYC is refrigerated or frozen, requiring 4,000 tons of refrigeration and 16 MW of power11. The center’s location in the floodplain, with a lack of reliable source of backup power, means that over 20% of New York City’s food supply would be jeopardized in a flood or coastal storm event. - Water

Nearly 50% of the entire city’s wastewater (625 million gallons per day) is systematically conveyed to, treated at and released from the four Wastewater Resource Recovery Facilities in the area12. There are four MS4 (municipal separate storm sewer system) outfalls within the Inner Long Island Sound where untreated rainfall is released from the storm sewer into the waterway after running off of roofs, sidewalks and streets. On its way, it picks up contaminants from silt, fertilizers, herbicides and heavy metals in motor oil, which are released untreated into the East River and its struggling ecology. - Energy

This area hosts major energy production for the city via power production facilities as well as for localized heavy industry and food distribution channels. The resulting release of various waste energy and externality pollutants means the Inner Long Island Sound is responsible for a massive carbon footprint.The Astoria Power Generation Facility produces about 20% of the total generating power for New York City13. Fueled by dirty oil and nonrenewable natural gas, the plant produces electricity through a process of steam, gas and combined cycle turbine generation before delivering it into the electric grid and powering New Yorkers’ homes, businesses and streets. Thermal energy, which is a byproduct of this process, is currently released into the adjacent atmosphere and waterways. The plant is part of a 300-acre complex on the Queens banks which also stores electric power, oil and liquefied natural gas. The majority (62%) of the plant was installed prior to 197114, making it ripe for renovation.The concentrated industrial facilities in the area generate huge demand for power generation. For example, the wastewater treatment facilities produce an estimated 570k tCO2e per year, the equivalent of 118k vehicles or the amount of energy provided to 63k homes in that same time frame (EPA Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator).

3. A Pivotal Moment

Looking at current infrastructure within the area, the model of leaky linear infrastructure is apparent — but so is the opportunity to leverage the confluence of systems into new models of operating. The historic decision to drastically reduce the city’s jail population and permanently close the Rikers Island jail complex opens 413 acres and 10 emptied buildings of opportunity. With the future of Rikers Island on the table and countless visions crafted across the district, there is opportunity now to build out a model for urban scale circular innovation within NYC.

From sites of consequence to good neighbors

By taking a systems view, designing with a focus on restoration and regeneration, and prioritizing inclusive and equitable economic development at every step, investment in the Inner Long Island Sound can promote innovation and growth citywide. With both operational and design tactics grounded in circular strategies and principles, we can begin to turn the externalities from the Inner Long Island Sound into valuable inputs for a circular and regenerative urban economy. Altogether, these circular innovations could yield thousands of jobs and training opportunities for neighboring communities.

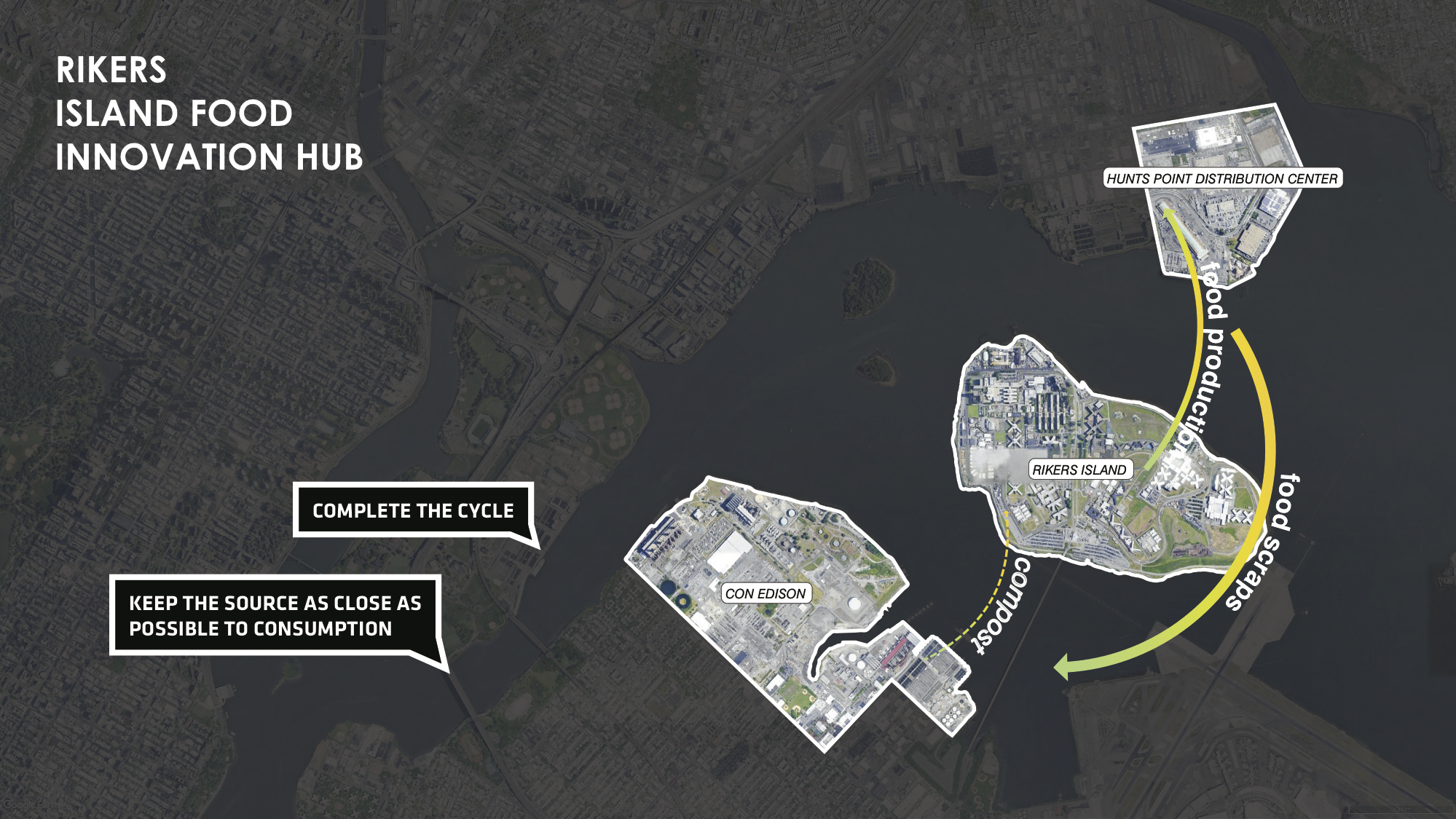

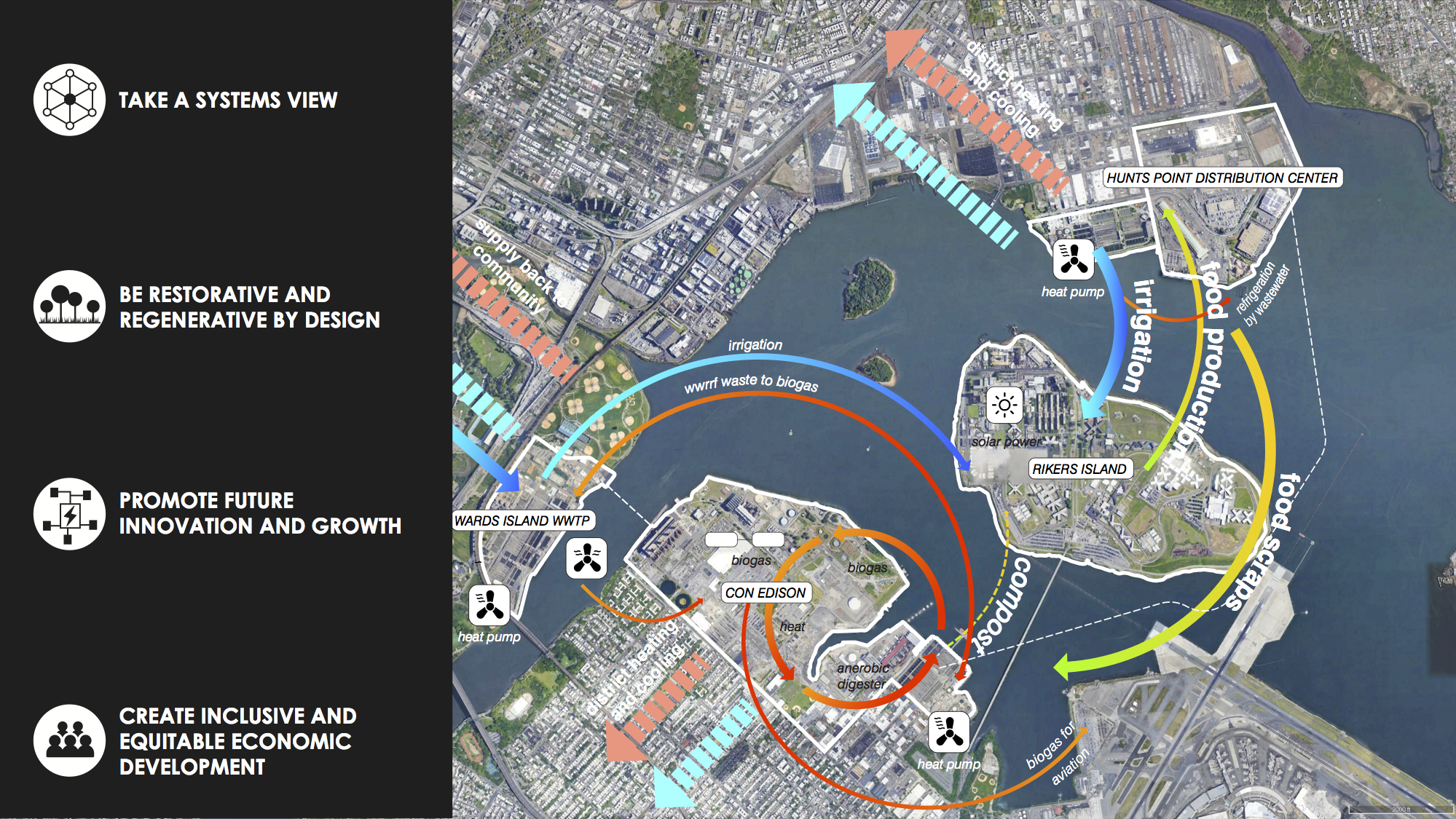

Rikers Island Innovation Hub – Produce and Complete the Cycle

Rikers Island could be the catalyst for food production and innovation to supply Hunts Point Food Distribution Center, which in turn could provide food scraps to drive efficiency at wastewater resource recovery facilities, which then could provide biogas and compost back into the production cycle.

By completing the food cycle and keeping the production, consumption, and waste recovery as proximate to the source as possible, we increase the economic and environmental value to the neighboring communities.

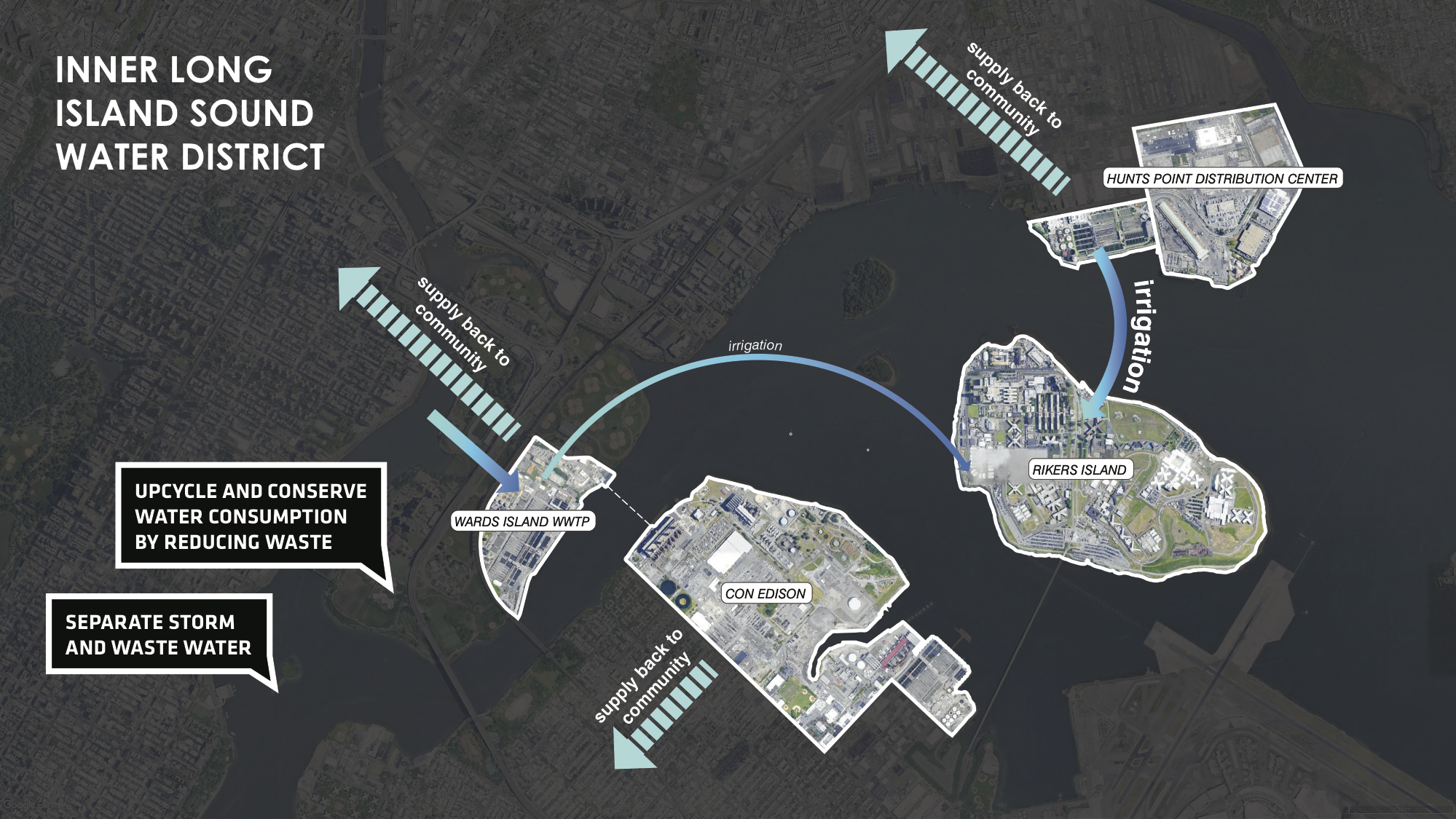

Inner Long Island Sound Water District – Upcycle and Conserve

Currently an energy and resource sink, the Inner Long Island Sound Water District will be an energy-independent, resilient working waterfront. With 1 billion gallons of water consumed by NYC each day and 1.3 billion gallons discarded into our oceans each day, we have what we need to reduce consumption from our freshwater reservoirs. Water Resource Recovery Facilities currently discard wastewater into our nearby oceans, though it is safe for use for secondary functions such as toilet flushing, irrigation, laundry and washdown. Providing infrastructure to upcycle this current waste would allow up to a 78% reduction of upstream consumption. Separating storm and wastewater will also help us preserve our precious water supply and reduce pollution of our nearby waterways.

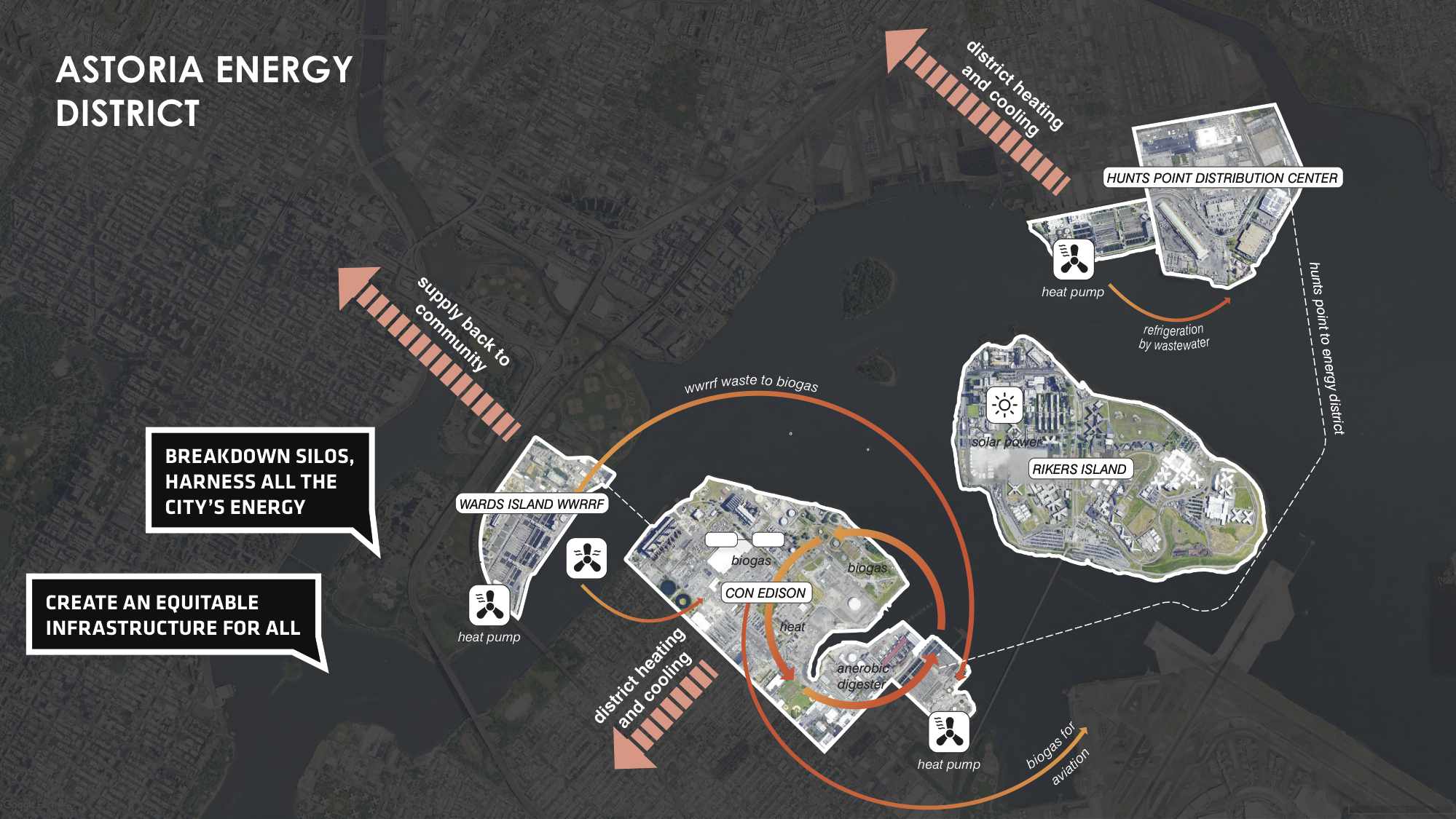

Astoria Waste to Energy District

Breaking down silos and harnessing energy from sites across the Inner Long Island Sound creates a more equitable infrastructure. Harnessing thermal energy from both the wastewater treatment plants and year-round refrigeration at Hunts Point could provide district heating and cooling systems for neighboring communities. Using anaerobic digesters with high solid contents to produce biogas could feed nearby

electrical plants and transportation. Thermal energy waste from these plants could then be fed back to digesters and nearby communities through the use of electrical heat pumps. Even nearby waterways, which have the strongest currents in and around NY, could be used to supply renewable energy.

The Big Picture

The infrastructure in our city was built on ancient principles. It is time for a redesign. We must look to the future and redefine the timeframe for change. To achieve these goals, we must focus our energy not on fighting the old but on building the new.

Redesigning systems within the Inner Long Island Sound shows how pairing capital investments with a reach across jurisdictional siloes can unlock exponential opportunities to repurpose, reduce demand for, and restore precious resource streams. Further, it demonstrates how progressive social policies, like reducing incarcerated populations, can have a positive physical and economic effect on such environmental concerns; providing employment opportunities and opening 413 acres of land for program in New York City’s green economy.

The potential demonstrated at the Inner Long Island Sound is just the start for the novel, yet replicable and scalable, models of urban circularity that New York City can embed in urban investments across the five boroughs. Each of us in our everyday work shaping this city must strive to work across disciplines to adopt a systems view, design with an ecologically and socially restorative mindset, and approach each project as a way to innovate the model. Doing so will bring us closer to a net-zero – nay! net-positive – New York City.

Authors ↓

Lida Aljabar believes in an urban future that is both resilient and just. She leads HPD’s neighborhood planning and climate adaptation in Rockaway, Queens. Previously, Lida led nation-wide urban resilience initiatives at The Trust for Public Land and managed public-private partnerships for community development in Arlington, VA. She has presented internationally on cities, climate change and social equity.

Brandon Cappellari is a Senior Landscape Architect at Bjarke Ingels Group. Previously, he was an Associate Principal and Landscape Architect at SWA/Balsley. His strong technical and intellectual leadership skills are exhibited daily in the studio and he has proven to be an effective communicator and liaison between design team members, sub-consultants, contractors, and clients. He is a passionate and motivated professional who thrives in a collaborative team environment.

Michael Izzo is Vice President of Construction at Hines and is responsible for capital projects within the Hudson Square Properties portfolio. Michael focuses on strategic planning of discretionary capital and new development projects. More recently, he has been leading the Hines team to evaluate climate change impact and risk on an existing building portfolio of twelve buildings equalling six million square feet. Michael is a strong advocate for circular system design and developing partnerships across the global markets to continue Hines’ commitment to sustainability. Currently Michael is organizing collaborations across all sectors of the quadruple helix model to achieve the most innovative results. Prior to joining Hines, Michael worked as a mechanical engineer in various capacities within the hospital and laboratory community.

Amy Macdonald specializes in providing clients with strategies to offset physical, operational and financial risk. Her experience spans four continents and includes reconnaissance following catastrophic hurricanes, earthquakes and floods, along with development of integrated, multidisciplinary resilience strategies. Amy leads the design of high profile risk reduction and climate change adaptation strategies for healthcare, commercial and real estate clients throughout the US northeast.

Rebecca is an urban designer and the Senior Urban Design Manager at the NYC Public Design Commission. Her work is concentrated on design policy and regulatory design review of architecture and urban design projects, with a focus on affordable housing, mixed-use developments, and urban systems. She leads the Designing New York: Quality Affordable Housing and Prefabrication in the Public Realm initiatives and also manages on the Commission’s special projects such as Women-Designed NYC and the Annual Awards for Excellence in Design. Her prior experience spans architecture, urban design, and ethnographic research, where she has explored the intersection of planning, policy, and design of the built environment to promote quality and equity in the public realm.

Autumn Visconti is a Senior Landscape Architect at BIG leading the East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) and the Brooklyn-Queens Park (BQP) projects. Her approach has been devoted to better preparing cities, communities, and regions for climate adaptation. This direction evolved into designing and developing climate resilient strategies for the national Rebuild By Design and The Mississippi River Delta Changing Course competitions.

Works Cited

1. NRDC: Estimating Quantities and Types of Food Waste at the City Level, 2017

2. NYC DEP: Wastewater Treatment System

3. Wall Street Journal: NYC Spends More on Recycling Collecting Than Regular Trash, 2017

4. Grow NYC Recycling Facts

5. Completing the Picture: How Circular Economy Tackles Climate Change, Ellen Macarthur Foundation, 2019

6. Closed Loop Partners, Capital Landscape Study, 2017

7. Waste to Jobs: Growing California’s Economy through Recycling, 2014

8. The Economic Impact of the Hunts Point Food Distribution Center, Hunter College New York City Food Policy Center, 2019

9. NYC: Hunts Point Lifelines, Rebuild By Design

10. NYC: Hunts Point Lifelines, Rebuild By Design

11. NYSERDA: Hunts Point Microgrid Final Report, 2016

12. NYC DEP: Wastewater Treatment Plants

13. PlanNYC: A Stronger more Resilient New York, 2013

14. NYISO: Load and Capacity Data, 2019

References:

A Stronger More Resilient New York. The City of New York, 11 June 2013, s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/sirr/SIRR_singles_Lo_res.pdf.

Completing the Picture: How the Circular Economy Tackles Climate Change. Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 23 Sept. 2019, www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications/completing-the-picture-climate-

change.

Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator. EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator.

Hoover, Darby, and Laura Moreno. Estimating Quantities and Types of Food Waste at the City Level. NRDC, Oct. 2017, www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/food-waste-city-level-report.pdf.

Hunts Point Microgrid NY Prize Stage 1 Feasibility Study. NYS Energy Research & Development Authority, 24 May 2016, www.nyserda.ny.gov/-/media/NYPrize/files/studies/15-Hunts-Point.pdf.

NYC: Hunts Point Lifelines, Rebuild By Design, https://www.rebuildbydesign.org/our-work/all-proposals/winning-projects/hunts-point-lifelines

The Economic Impact of the Hunts Point Food Distribution Center, Hunter College New York City Food Policy Center, 2019 https://www.nycfoodpolicy.org/the-economic-impact-of-the-hunts-point-food-distribution-center/

Recycling Facts. GrowNYC www.grownyc.org/recycling/facts.

Wastewater Treatment System, NYC Department of Environmental Protection, www1.nyc.gov/site/dep/water/wastewater-treatment-system.page.

West, Melanie Grayce. NYC Spends More on Recycling Collecting Than Regular Trash. The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 24 Aug. 2017, www.wsj.com/articles/nyc-spends-more-on-recycling-collecting-than-regular-trash-1503585000.

2019 Load & Capacity Data Report. New York Independent System Operator, Apr. 2019, www.nyiso.com/documents/20142/2226333/2019-Gold-Book-Final-Public.pdf/