Time-based zoning encourages more efficient land use and balanced growth for dynamic 24-hour neighborhoods.

By Luc Wilson

NOTE: Please explore the Google Places data web app developed by KPF Urban Interface to accompany this piece.

What if zoning considered time in regulating use and density? Would we allow greater built densities if activity was spread throughout the day instead of concentrated from 9 – 5? Temporal zoning promises the more efficient use of our city and better accommodation of future growth. Spreading activity throughout the day gets more capacity out of our transit system, our public spaces, and our sidewalks. 24-hour neighborhoods can produce safer streets, shortened commutes, and a more equitable distribution of jobs. The creation of time-based zoning regulations requires re-thinking traditional land-use classifications through the analysis of geospatial and temporal urban data sets.

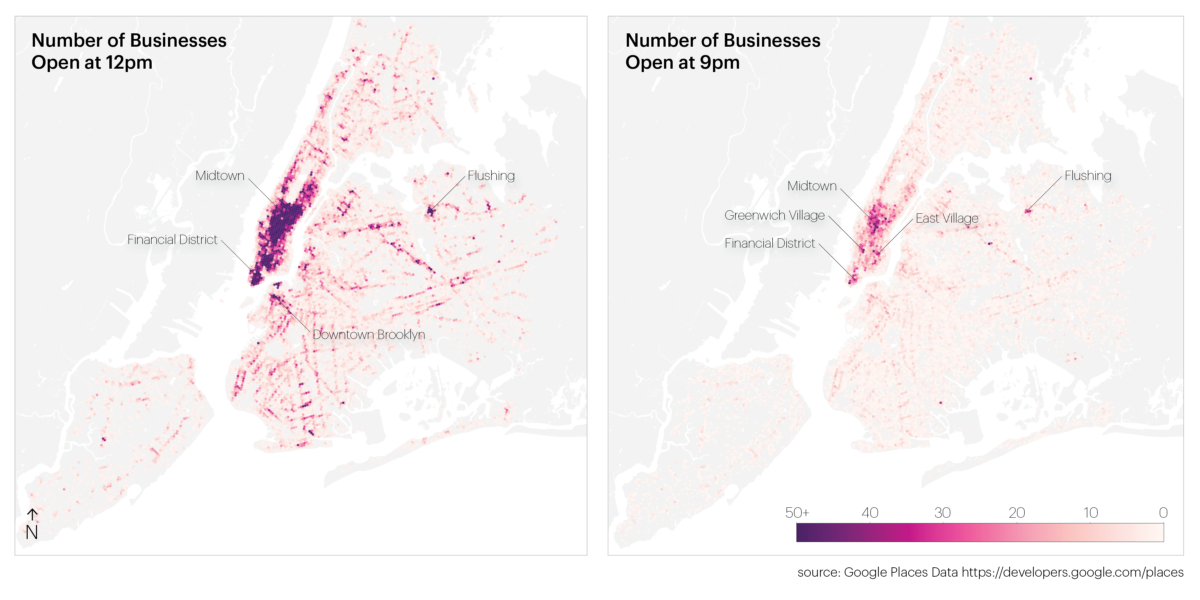

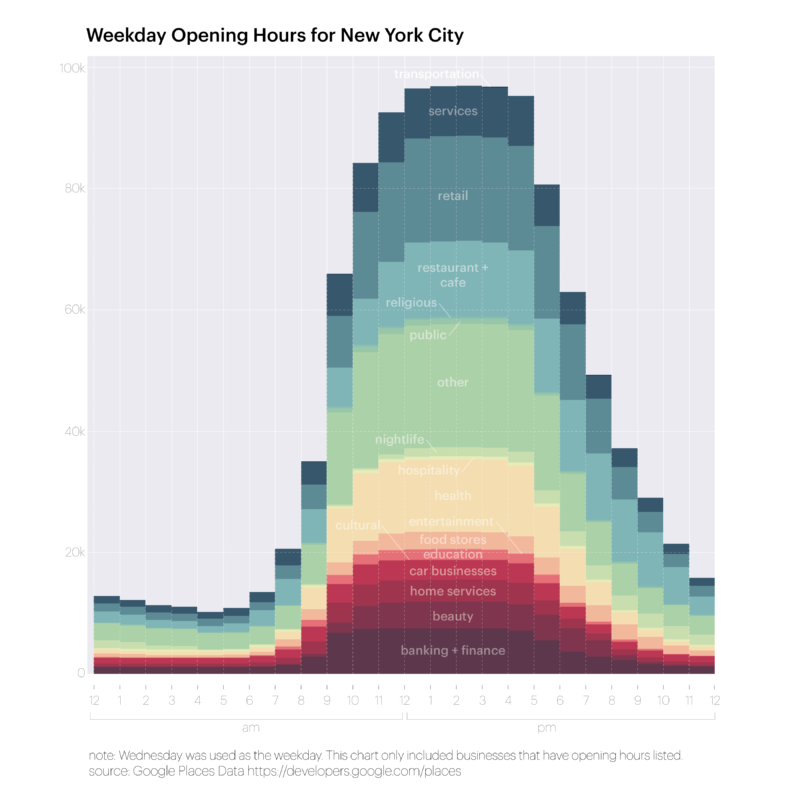

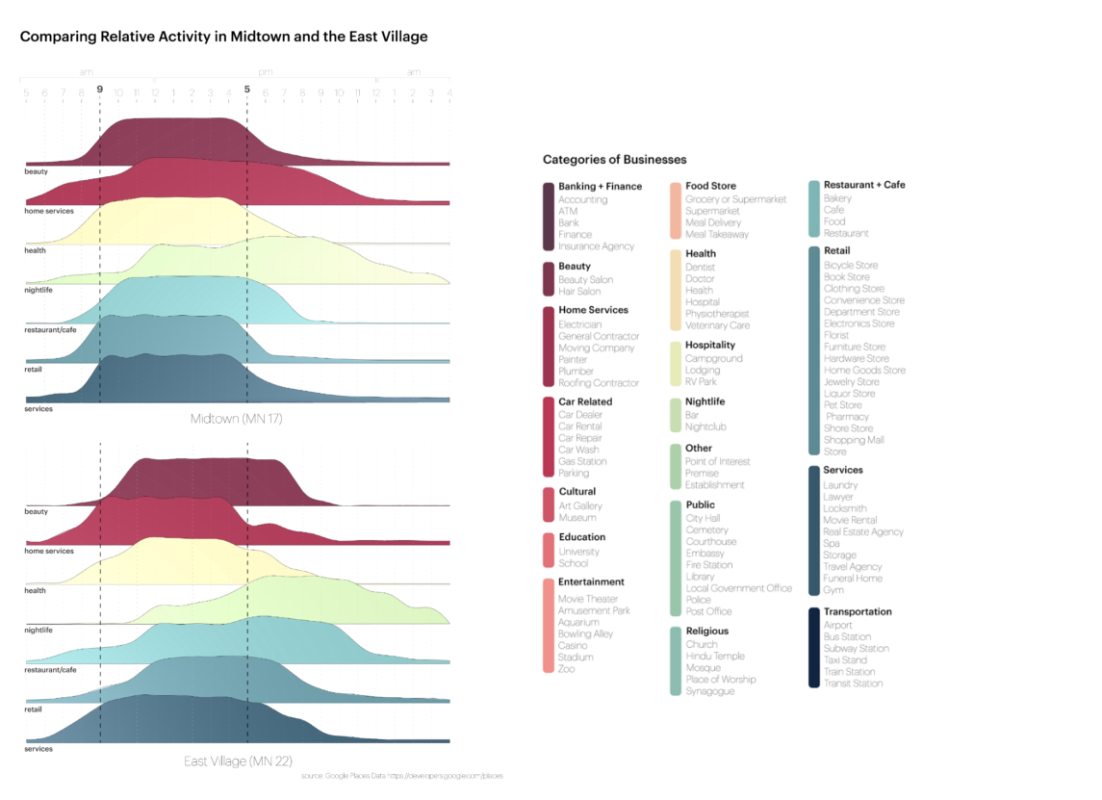

Traditional land use categories are static, ignoring the potential for temporal shifts in use, while uses and level of activity change depending on the time of the day and the day of the week. We can harness data that shows which uses are active at a given time across, like the Google Places data for New York (Fig. 1 & 2), to capture a snapshot of use intensity and how it changes from day to night. KPF Urban Interface has graphed activity levels for various use categories in Midtown and the East Village (Fig. 3), highlighting differences in patterns and distribution of activity throughout the day. Both neighborhoods ‘wake up’ around 7am, and while most Midtown businesses close between 5 and 7pm, beauty, retail, restaurants, and nightlife businesses tend to stay open later in the East Village. This suggests a more efficient use of the capacity of the neighborhood, through more consistent activity throughout the day.

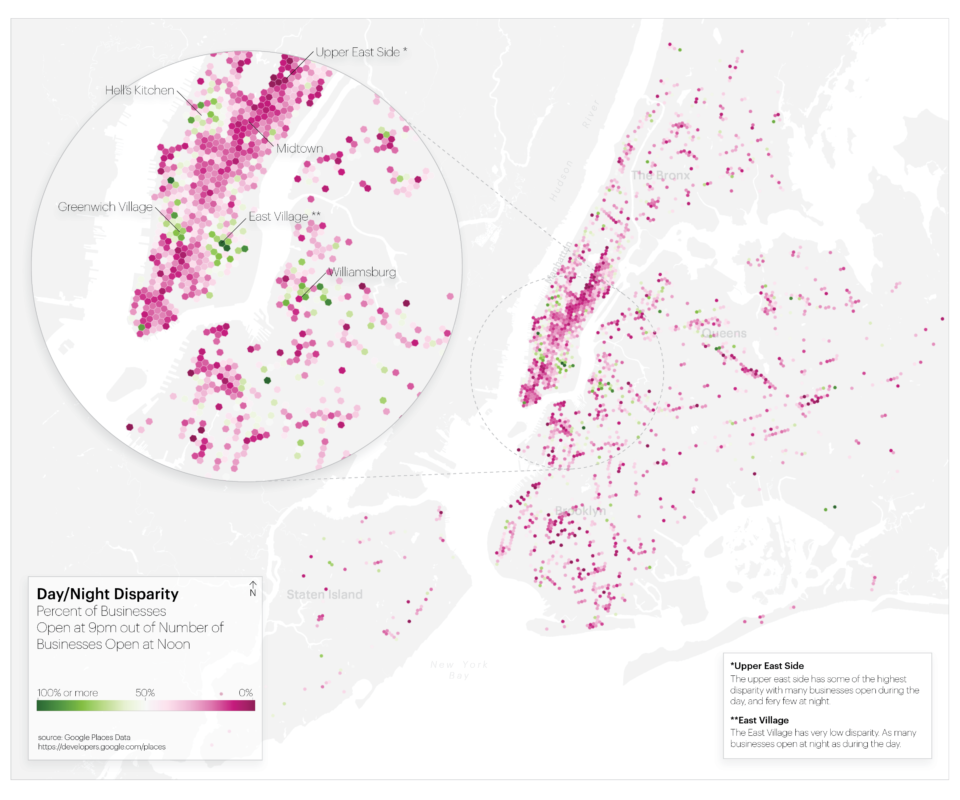

To illustrate how we might use an understanding of current efficiencies (or inefficiencies) of activity throughout the city to develop a time-based zoning framework, we created a map (Fig. 4) showing the disparity between businesses open during the day and at night. For instance, Midtown has a very high disparity because it has a significant number of businesses open during the day but far fewer at night. This high disparity could be considered inefficient since transit, amenities, and other services are designed to support daytime peak capacity. These neighborhoods could, therefore, conceivably accommodate more nighttime activity.

Finally, how could a zoning mechanism encourage time-based planning? A FAR (floor area ration) bonus tied to uses that spread activity across the day could provide developers with enough of an incentive to actively consider temporality. Such a spreading of use across time could address major concerns about increases in density: transit capacity, overcrowding of sidewalks and parks, and utility infrastructure capacity. However, to start crafting a time-based zoning regulation we first need a time-based land use data set: one that is comprehensive, unlike Google Places data, which offers an interesting snapshot of activity in the city but misses activity and use like residential buildings, which are not captured by Google.

As urbanists we preach the merits of the 24-hour city, but now we can and need to craft time-based zoning regulations that achieve it.

–