The Urban Design Forum’s 2018 Forefront Fellowship, Shelter for All, addressed the homelessness crisis in New York City by examining how to dignify the shelter system through better design and exploring the root causes of homelessness and housing precarity. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on how to address the prison-to-shelter pipeline, public bathrooms, public realm management, supportive housing, and racist housing policies, which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

Read interviews with Marcus Moore and Rob Robinson and Graham Ciraulo to accompany this proposal, and view the full compilation of Shelter for All proposals and interviews here.

By Alp Bozkurt, Johane Clermont, April De Simone, Nova Lucero and Emma Silverblatt

Theory of Change

In order to create policies, practices, investments and development that respond to human needs in just and inclusive ways, the subconscious interplay between dehumanization, stigmatization, and our negative perceptions of the oppressed in our society must be exposed and eliminated.

Abstract (Five Points)

- The origin of dehumanization is historically entrenched: From racism to classism to sexism, the American economy was built on the oppression of the poor, working class and people of color. False perceptions of black and low-income populations as subhuman were ingrained into our national consciousness to justify oppression.

- The codification of dehumanization has resulted in a weighted system: Beyond de facto practices, policy is still written mainly by those who believe in false perceptions, cannot empathize with the dehumanized, and who therefore systematize unjust blame and accusations of immorality onto oppressed populations. Resultant policy upholds a prejudiced agenda.

- The system profits the powerful and wealthy: Racist, sexist and classist policies today are less overtly justified, but continue to cause further dehumanization of oppressed populations while creating unnecessary industries that profit those in power.

- “Solutions” contribute to internalized oppression: The resultant systemic inequity reinforces false narratives of those who are oppressed and has a profoundly negative impact on the dignity of people currently experiencing homelessness. So-called “assistance” or “help” is actually objectification, infantilization, and dehumanization.

- We must personally work to create our ideal system that values people over profit: To break the cycle of devaluation, we must recognize our role in the perpetuation of the current system, focus on interpersonal action to work to change our perceptions, and join with others in collective action that challenges the policy of the current order. By exercising our agency together we can work to de-commodify housing and truly erase homelessness.

—

⅕

—

The Origin of Dehumanization

The dehumanization of people currently experiencing homelessness originates from profit motives created by exercising power over others. The powerful and wealthy have always privileged economic success at the expense of the other, exploiting the poorer classes as cheap labor or consumers from whom they generate wealth. By denying many equal pay, access to housing or education, these resources were reserved for higher classes.

For colonizing Europeans to even lay claim to the first property in this country necessitated the slow, calculated theft enabled by Native American genocide. Throughout this centuries-long extinction and displacement, Africans were simultaneously stolen from their homes to work that same soil. The product of this soil was cotton, shipped back overseas to fuel industrialization; and the subsequent rise of the most squalid, dangerous working conditions to which humans had ever been subjected. The exorbitant wealth created was not returned to the laborers, but instead consolidated by those in power, reinvested into factories, larger plantations, more product, more profit, further industrialization, eventually transforming this fledgling country into the most powerful nation in the world.

Further, the invention of race was used as justification for terrible actions. It made dispossession, murder and slavery of others not only reasonable, but accepted destiny for the white man. The belief in white ethnic superiority was elevated to a primary source of dignity following the humiliating loss of The Civil War, which cast many whites into the same abject poverty as their newly freed neighbors. Rather than allow “equality” to diminish whites, racist narratives became even more entrenched, written into every aspect of society from curriculum to legal segregation. Lower class Caucasians in particular bought into the falsehood that white supremacy provided–that whites were better and smarter than blacks–and for many–that blacks were subhuman. Economically, the invention of race has effectively been detrimental to the lower classes of all ethnicities, as those controlling the forces of production rely on it to divide the power of the working masses and prevent organized labor from coalescing.

Image credit: Forefront Fellows.

—

⅖

—

The Codification of Dehumanization

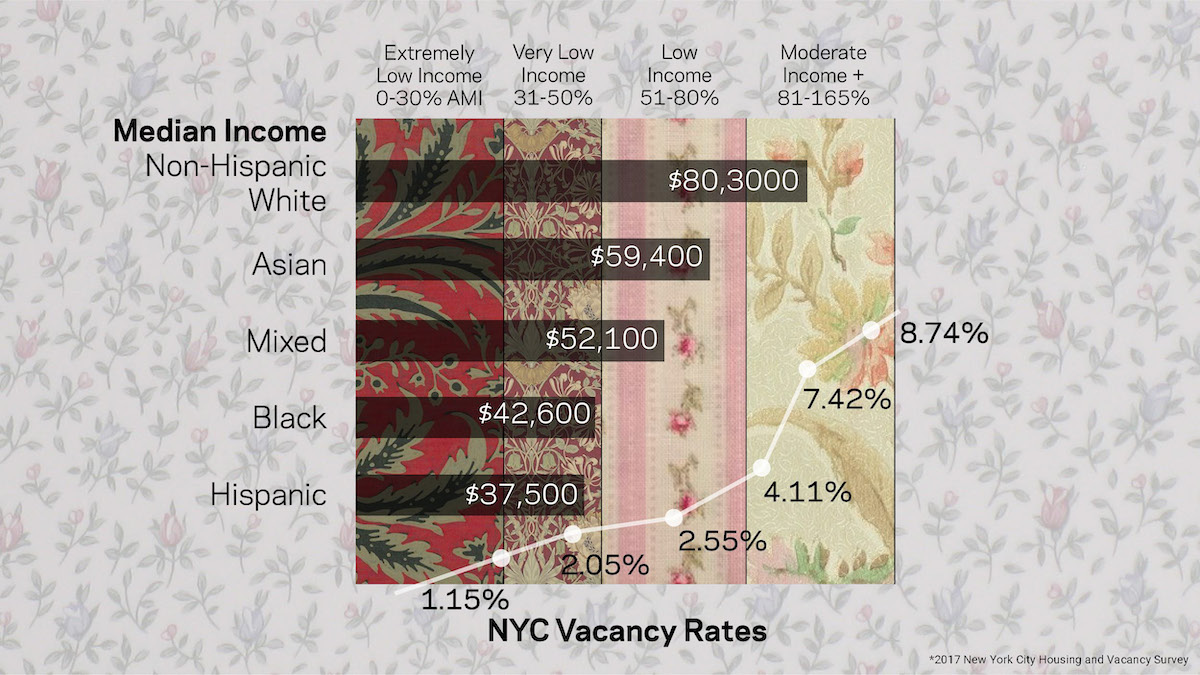

As those in power were always whites, these perceptions have infiltrated all spaces where decisions about the poor, people of color and their communities were made, from access to housing, banking opportunities, funding for local schools and parks, to the financial support of local businesses and entrepreneurs. Refusal to grant opportunity to these groups prevented any real increase of their net worth over time. By combining racism and classism, those in power were able to demonize people of color as guilty of spreading crime, immorality, poverty, and not being American. Selectively-deployed tools like redlining and ‘slum-clearance’ projects reinforced these points politically. But to whose gain? White flight and the formation of the suburbs were not just the direct result of fear-mongering against the spread of “undesirables.” The demonization of black people has also been extremely lucrative for the developers of segregated housing, the manufacturers of automobiles, and in short, the engineers of the consumerist American Dream. And how was this outright discrimination achieved? By diverting funding and resources away from the inner city and accelerating the rise of poverty among those who were never given access to the same home loans as whites.

Legal racist imperatives may have become less overt, but in practice today are even more insidious. Racist perceptions are now so deeply buried in our subconscious and conflated with classism or imposed morality that it becomes difficult to recognize and remove them. We navigate our current realities often unaware why entire communities of poor and people of color have remained poverty-plagued for decades. We do not recognize how housing developments upon which the middle class built their wealth simultaneously sealed the fate of those left behind, those perceived as undesirable. In his book, “How Racism Takes Place”, George Lipsitz informs us that, “For nearly four decades, HUD pursued policies that restricted low-income Blacks to central-city segregated neighborhoods despite clear legal obligations to create housing opportunities throughout the metropolitan area…[which] privileged the exclusionary desires and preferences of suburban whites over the agency’s legal obligations to take affirmative steps to decrease segregation.” With private incentive and clear public mandate to serve the right neighborhoods, politicians and urban planners preferenced the needs of suburban growth. This can be directly observed in the built environment: commuter highways bisect poor communities of color in every major American city, a practice which displaced thousands of people through racially-targeted eminent domain. The direction of public funding exclusively towards the suburbs also inherently implies the total disinvestment in infrastructure and services for inner city communities, leading to a host of insurmountable hurdles facing Americans of color such as: poorly-maintained, dangerous, or uninhabitable housing stock; inadequate education systems; physical disconnection from economic centers or transport; and in short, complete inability to realize any of the intergenerational wealth that white Americans were busy stockpiling in suburbia.

—

⅗

—

The System Profits the Powerful and Wealthy

Today’s elites still benefit from keeping the poor in inhumane conditions, underpaid, doubled up, in shelters and on the streets. Developers are encouraged to continue ignoring the low-income populations in New York City. There is no profit motive to produce truly affordable housing and no government incentive demanding it. There is, however, an abundant profit to be made by catering to global elites who collect starchitect-designed penthouses. There is profit to be made by exploiting historic communities of color, once ghettoized by redlining, where aging homeowners are desperate to cash in on the last residential lots left to be gentrified. Thanks to a lack of regulation and unfettered speculation, land values can keep rising in lock-step with the capitalist tendency towards greed. When the bubble bursts, the people who lose are still those at the bottom. The government coughs up a bailout of public tax dollars. The 1% sweeps the table clean.

There is no profit motive to produce truly affordable housing and no government incentive demanding it.

So, it is more profitable for developers to build “luxury” residential buildings by pushing low income populations out. But where do they go? This is convenient displacement for the heads of private companies who benefit from keeping prisons and shelters full. Our penal system’s overzealous incarceration of low-income populations decimates communities, removes wage earners and handicaps families. Racist policing and laws that harshly criminalize the plight of low-income populations are undeniable: 56% of all incarcerated people in 2015 were African Americans or Hispanics, though they make up only 32% of our population. Those incarcerated are never the same. They become convicts. Convicts bear the moral weight of this stigma for the rest of their lives, in addition to the legal loss of access to housing, employment, education, and loans. It is estimated that 6 million potential voters were disenfranchised by felony convictions in the 2016 elections – voters who would have predominantly represented the viewpoints of low income or minority Americans.

It is surprising to some to learn that different homeless shelters, despite supposedly fulfilling the role of refuge from the pressure of capitalist inequity, are permitted to charge wildly variable rates for stays in their facilities. Little explanation is provided for these differences and costs are wholly uncorrelated to reported inconsistency in services. On average, these monthly rates (footed by funding from all levels of government), far exceed what sponsoring a market rate apartment rental would have cost in the first place. Even so, all the shelter services in the city can neither erase an eviction or bad credit from one’s record, nor the practice of rejecting one’s future housing applications for these reasons. It would seem that shelter funding is not money well spent towards a ‘solution’ for the housing crisis. Whether low income populations are held captive in physical prisons, shelters, or in marginalized neighborhoods lacking access to opportunities that provide living wages, the system allows those in power to suck federal funding streams dry under the guise of ‘assistance’ to support overwrought solutions aimed only at the symptoms of systemic inequity, while perpetuating the disease.

—

⅘

—

“Solutions” Reinforce Internalized Oppression

Our current system of government was clearly set up for the poor, working class, communities of color, otherly-abled and those living with a mental health illness to fail. And by fail we mean to not survive at all. Restriction from accessing the same resources as others, such as education, ensures that these populations will not be able to secure the majority of positions of power in which decisions about them and their communities are made. George Lipsitz argues that “racism, heterosexism and class oppression leave members of aggrieved groups with few opportunities to advance their interests inside the political system.” (Lipsitz, p.127) However, being permanently disadvantaged politically and economically and often physically marginalized is not seen as an excuse for what our society deems as an unacceptable failure to ‘make it.’ In particular, the demonization of black inner-city residents has gone virtually unchallenged for decades in popular culture and public policy. The silence on this oppression from inside and outside of the system sends a loud and clear message to those currently experiencing homelessness of their low value and place in society.

The experience of being homeless in a shelter or on the street is aggrandized by society’s so-called “solutions” which in practice function to psychologically and physically dehumanize and stigmatize our neighbors. In shelters, independence is quelled and morale is kept low on the basis of infantilization and hyper-regulation. The compliance-based bureaucracy necessary to convert people into federal checks is swift to deem them incompetent as they fail to follow draconian procedures. Even after they are made to prove their problems, even after they are judged eligible for help, they better make it back to the shelter before 10:00 pm or risk being turned away, because our willingness to help a fellow human is conditional on arbitrary rules. In conversations with shelter “clients” (as they are termed by shelter operators) unreasonable conditions of service and staff interactions were cited above all as the cause of their overall negative experience. It is control, unequal power relationships, disrespect, and an abuse of authority by shelter staff that cement the feelings of feeling less than, even less than human for some.

Indeed, the shelter system perpetuates the false narrative that only the well-behaved and therefore deserving will be given a bed or room. In one study in Portland, people currently experiencing homelessness shared that “they did not feel they were treated as fully recognized adults or respected as equal citizens, but rather as numbers and children.” In the same article the study authors express that a possible reason for this impact is that “an emphasis on the numbers and statistics diverts attention from experience in the social service system.” Anyone who has stepped foot inside a shelter can attest to how the institutional, untended surroundings combined with the patronizing or sometimes even cruel attitude and behavior of tightly-stretched shelter and social service providers inevitably creates this feeling for individuals and families. Lipsitz argues that place has a profound impact on the individual, “crowded together in cramped quarters, competing with each other for scarce resources, and seeing the mark of their own humiliating subordination in the people whose identities they share, their hatred of oppression can easily become channeled into self-hatred. [As a result] people forced to live close together by oppression are often at each other’s throats.” Not to mention, the physical environment necessitated by a building that treats human lives as interchangeable, is by nature one in which “minimal provisions… and minimal privacy… express a vision of the homeless as bare life, as beings stripped of human personhood and individual identity.” People currently experiencing homelessness often choose to opt out of this system not only for personal safety reasons, but also to maintain self-respect and a feeling of control over their surroundings. “Even in the face of economic and political marginalization, people make claims on their dignity and rights as respected adults.”

—

⁵⁄₅

—

Call to Action

It is the lived experience of those who went through this process of dehumanization that demonstrated to us the strong need to draw attention to the systematic and paradigmatic problems with social service provisioning and structural inequalities rather than focus our research on the “perceived failures” of individuals, as many current solutions wrongly do. None of New York City’s attempts to eradicate homelessness will be successful under our racist and patriarchal systems. To address this issue meaningfully requires that every one of us does work to eradicate it internally and collectively. We must first acknowledge the role that race plays in the oppression of the poor and minorities. We must recognize how race has and is still being utilized by the powerful to divide and conquer us, to perpetuate the inequity that benefits their status and wealth. We must challenge our life’s work and understand who profits from our actions. We must identify the role we continue to play in depriving others of resources, and how we personally contribute to ongoing systemic oppression for our own gain.

We need to meet each other as individuals to be able to empathize with struggles that we have not experienced and to learn to think beyond the historic narratives that color our perception.

After we understand where this perspective came from and where it leads (our complicity), we must work to rectify our relationship to those we have been dehumanized. We need to meet each other as individuals to be able to empathize with struggles that we have not experienced and to learn to think beyond the historic narratives that color our perception. We must erase the divisions that have been built into our society. After we take the time to care, empathize and understand will we finally be able to recognize all people as equal to ourselves.

Only with this self-awareness can we thoughtfully conceive of solutions that maintain dignity and humanity. We can then effectively use our agency to join in collective action with those being oppressed to challenge current systems and build a new system. We can help to build solidarity between poor and working-class communities of color, and poor and working-class white people. And we can fight for policy that respects and represents everyone as humans deserving of the same rights.

Everyone should have the right to safe and adequate housing. Housing has a door with a key and promotes the feeling of security and dignity that comes from having control over yourself and your environment. The ‘pull yourselves up by your bootstraps’ myth of success in America created the perception that those without housing are simply undeserving of these things. But how can a person be undeserving of the space they need to live, to breathe, to think, to be? To ‘deserve’ is a moral imposition conflated with the ability to ‘afford.’ Who commodified the space we take up? Do we agree with it? Housing is not entered through a metal detector. Housing is not a lights-out-at-ten shelter. Housing is not a room shared with twelve strangers and a bathroom with no lock. We call on everyone to work with us to dismantle their outdated belief systems, to de-commodify housing and to humanize our neighbors currently experiencing homelessness.

Authors ↓

Alp Bozkurt is an award-winning designer who takes a generalist approach to Architecture with a firm belief in its power to create equitable communities and the larger impact design can have on society. He has experience as a project manager and designer throughout the United States and Europe where he has worked on projects varying in scale and typology from multi-family residential to art galleries, schools, and supportive housing. Alp is currently a Senior Designer with Marvel Architects in New York City.

Johane Clermont is a Senior Urban Designer and Planner at WXY Studio. Prior to joining Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU), Johane was a City Planner at the NYC Department of City Planning where she was the Zoning Division’s lead planner on industrial manufacturing policy and development. There, she worked to create new models of innovative mixed-use districts and zoning envelopes to modernize, respond to and set policy for the evolving needs of the City’s industrial manufacturing economy.

April De Simone is Co-Founder and Managing Partner at designing the WE. She has over 15 years of experience in strategically designing, developing and launching for-profit, non-profit and government projects. Continuing to advocate for social innovation, Ms. De Simone is co-creator of various for-purpose ventures and initiatives that promote market based solutions to address complex social challenges. A Dean Merit Scholar, she recently completed her Master of Science in Design and Urban Ecologies from Parsons the New School for Design. Ms. De Simone continues to be recognized for her leadership and dedication in supporting frameworks that promote a just and equitable society.

Nova Lucero is a Tenant Organizer at The Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition working with tenants in the Bronx to create tenants associations and fight for better housing conditions for tenants across New York State. She previously worked with Northern Manhattan tenants and residents creating tenants associations and fighting the city proposed rezoning for Inwood, as well as an Eviction Prevention Case Manager and Housing Specialist in the South Bronx, with families facing eviction and currently living in the shelter system. Nova graduated from Fordham University with a B.A. in Political Science.

Emma Silverblatt is an Associate at SO–IL. She previously worked on the World Trade Center Performing Arts Center as a designer at REX. She believes an equitable society begins with Housing as a Human Right and that architecture is inherently political. Emma completed her Master’s thesis on low-income housing at the Harvard Graduate School of Design by creating a participatory development strategy with Picture the Homeless, a grassroots organization of homeless individuals, to promote their vision for permanently affordable housing in land-use discussions with local government.

Header image credit: Forefront Fellows