The Urban Design Forum’s 2018 Forefront Fellowship, Shelter for All, addressed the homelessness crisis in New York City by examining how to dignify the shelter system through better design and exploring the root causes of homelessness and housing precarity. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on how to address the prison-to-shelter pipeline, public bathrooms, public realm management, supportive housing, and racist housing policies, which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

Read interviews with Tommy Newman and Jessica Katz to accompany this proposal, and view the full compilation of Shelter for All proposals and interviews here.

By Anand Amin, Jenneh Kaikai, Andrew McIntyre, Catherine Nguyen, and Rebecca Sauer

Supportive housing is at the center of New York’s response to the homelessness crisis, but its development is constrained by land scarcity and unfavorable land use policies.

Collectively, New York City and State have committed to 35,000 new supportive homes. However, if the status quo holds, they are in danger of falling short of their goals. We believe we can hit that target by accelerating supportive housing development in New York City, forging new public partnerships, and amending zoning regulations.

Supportive housing is permanent affordable housing with embedded social services for vulnerable individuals and families, people experiencing homelessness and living with disabilities or other barriers to maintaining stable housing. It was created in New York City in the 1980s as a response to modern homelessness caused by rising rents and displacement in previously disinvested neighborhoods, regulations discouraging single room occupancy (SRO) units, and deinstitutionalization of people living with mental illness. Nonprofits and faith-based organizations created supportive housing with a patchwork of small government and private grants. According to the Supportive Housing Network of New York, “Between 1955 and 1992, the State’s in-patient psychiatric hospital population fell from more than 90,000 to less than 13,000.1 Thousands of mentally ill individuals were discharged without the financial subsidies or social supports necessary to secure or maintain stable housing.” Simultaneously, New York City experienced a dramatic reduction of SRO units. This meant that vulnerable and low-income adults lost a primary foothold in the housing market.

The supportive housing community grew in the 1990s as it became a proven model to end chronic homelessness.2 At this time, a series of three funding agreements were drafted between the city and state, known as the “NY/NY Agreements.” Together, the NY/NY Agreements created 14,000 units of supportive housing for individuals and families.3

“I think [H+H] can be the best health care provider for people for whom social determinants are the dominant cause of their illness. I want to be the best provider to the homeless, incarcerated, mentally-ill, very low-income, and those with Medicaid.” – Dr. Mitchell Katz, President & CEO, NYC Health + Hospitals

Today, according to the Supportive Housing Network of New York, there are 32,000 units of supportive housing in New York City, comprising multiple program types and serving a variety of populations, including young adults, families, and veterans. However, according to the most recent count by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), there are over 78,000 people experiencing homelessness.4 A key strategy to address this crisis is adding new supportive housing stock. The City and State have embraced this goal by committing to creating 35,000 units of supportive housing in 15 years, via their respective NYC 15/15 and Empire State Supportive Housing Initiative programs.5, 6

As we spoke to government officials and other experts in the development, advocacy and policy communities, a common theme emerged: Regardless of unprecedented capital, social service, and operating resources for supportive housing at the city and state level, finding affordable and buildable sites is a major impediment to reaching development goals. Siting supportive housing can be a challenge due to community opposition stemming from stigma, misinformation, bias, and fear. Furthermore, supportive housing is often directly competing for land with traditional affordable housing, senior housing, and market-rate development.

With these constraints in mind, we set out to identify tools to unlock opportunities to develop supportive housing, on public as well as private sites.

Image credit: Vanni Archive Architectural Photography.

CAMBA Gardens: CAMBA Gardens was completed in 2018 as a partnership with NYC Health + Hospitals and non-profit developer CAMBA. The development was built on the grounds of the Kings County Hospital, on the site of a disused psychiatric facility. The two residential buildings include 502 apartments, with 328 set aside for formerly homeless families and individuals. Co-locating housing and social services with the physical and mental health resources of a public hospital streamlines tenants’ wellness plans and provides a platform for rebuilding their lives.

Image credit: Johnston Davidson Architecture / City of Vancouver.

Pacific Spirit Terrace: Fire Hall No. 5 in Vancouver, originally built in 1952, was out of date. It did not meet current seismic codes, the driveway was too short, and additional space was needed for fire trucks, dorms, and training. The redevelopment of this site into Pacific Spirit Terrace includes a two-floor fire hall, and four floors with 31 two- and three-bedroom units of supportive housing for families, as well as amenity spaces, operated by the YWCA. Many residents will be survivors of domestic violence and, while firefighters will not double for security services, their presence could function as a safety mechanism.

Public Partnerships and Public Sites Analysis

Public land has always been an important ingredient in supportive housing development. The cost is often far below market value ensuring development budgets are more feasible. Moreover, the government has more control over its use. Unfortunately, public sites under the jurisdiction of agencies tasked with housing, traditionally used for supportive housing development, are dwindling.

A city policy of identifying public land for supportive housing is not without precedent. On July 13, 2013, New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), Department of Housing, Preservation and Development (HPD), and H+H put out a Request For Qualifications (RFQ) to non-profit sponsors for the design and construction of supportive housing development projects. 44 sponsors were qualified through this process, 11 sites were designated, and six are currently completed or under construction.

Inspired by case studies here and in other cities, we identified five key agencies with untapped development potential: NYC Health and Hospitals (H+H), NYC Fire Department (FDNY), United States Postal Services (USPS), New York City Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), and New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS).

H+H: H+H is New York City’s public hospital and healthcare system, charged with caring for many of the city’s lowest income residents and those experiencing homelessness. Given H+H’s mission alignment, past experience and future intention to develop supportive housing, they were a natural choice for inclusion in our analysis.

“People need health care, but the major thing they need to have good health is housing. That’s why I want to figure out how to donate more land to similar projects.” – Dr. Mitchell Katz, President & CEO, NYC Health + Hospitals

Building on the success of the RFQ and projects like CAMBA Gardens, H+H announced in April 2019 a commitment to continue using their land to develop supportive housing. At the opening of the Woodhull Residence, a building with 89 units of supportive and affordable housing built on the parking lot of a public hospital in Brooklyn, the agency’s CEO and president Dr. Mitchell Katz said, “We have a cure for homelessness. It’s called a home. It’s 100 percent effective it has no side-effects.” He added, “The important question is, now that we’ve proven that we can do it, how can we do a lot more of it?”7

FDNY: Inspired by Pacific Spirit Terrace in Vancouver, we analyzed FDNY-occupied sites. Some FDNY properties are outdated facilities in need of improvements and upgrades. Other FDNY sites are underbuilt, used for parking or storage. While noise is clearly a concern when co-locating an active fire station with housing, it is possible to address through engineering and soundproofing, as was done at Pacific Spirit Terrace. Whether the FDNY facilities are decommissioned or rebuilt, supportive housing could be located on these sites.

USPS: We studied US Postal Service sites because their business model is transitioning to a smaller real-estate footprint. The 2018 Sustainable Path Forward report recommends capturing additional value from existing retail offices by converting them or co-locating other uses.8

ACS: The Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) provides services for New York City’s children and families in the areas of child welfare, juvenile justice, and early care and education services. The mission of the agency–to provide stability for vulnerable New Yorkers–aligns with supportive housing goals. Increasingly, supportive housing is serving families as well as individuals. Co-location of supportive housing with an ACS use such as an early childhood education center could provide a strong community benefit.

DCAS: Finally, we reviewed sites under the jurisdiction of the Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS), which manages, acquires, sells, and leases city property. Compared to other city agencies, DCAS has one of the largest inventories of vacant or underbuilt lots. While there is substantial competition for this property from other city agencies, these sites should be prioritized for supportive housing given the scale and reach of the homelessness crisis.

Methodology and Findings

Through a desktop GIS soft-site analysis, we identified publicly-owned sites under these five jurisdictions with the following criteria:

- Site area more than 5,000 square feet

- 50% of the site is underbuilt or soft

- Available residential, commercial, and/or community facility floor area

- Accessible by transit

- Near services and neighborhood amenities

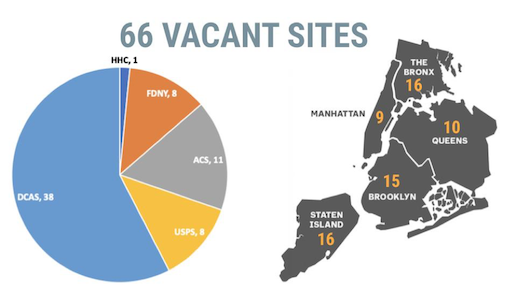

Out of 466 soft sites, we identified 66 vacant sites primed for development, the majority of which are in DCAS jurisdiction.9 The vacant sites are spread across the boroughs. Most are parking lots, overgrown with vegetation, or playgrounds needing improvements. These sites are immediate opportunities for the city to activate underutilized vacant land and develop supportive housing.

Distribution of 66 vacant sites by agency and borough.

As an immediate step, we recommend that the city start engaging with these agencies and begin the redevelopment process for the identified 66 vacant sites. Next, we recommend that the city expand upon this analysis to include other potential agency partners to create a citywide inventory of public sites ripe for supportive housing. Lastly, we strongly recommend the Mayor and the City Council agree to new policies that commit, enable, and encourage city agencies to redevelop city-owned vacant and soft sites with supportive housing.

Unlocking Private Sites

Because the opportunities to develop publicly-owned sites are limited, privately-owned sites are integral to meeting supportive housing production goals. Our analysis of private sites revealed the ways in which supportive housing development is constrained by zoning regulations, leading to recommendations about how to revise zoning to maximize desperately needed new housing.

We focused on zoning districts most common and viable for supportive housing. These districts include the non-contextual R5-R8 residential districts, which produce a variety of low- to mid-density housing, and are dispersed across the city.10 However, in R5-R8 districts, zoning regulations are severely restrictive to supportive housing when compared to other types of housing. Our analysis solves for the extremities, ensuring our recommendations could be applied more broadly across all residential districts.

“I don’t really like cars, so I’d rather build housing for people.” – Dr. Mitchell Katz, President & CEO, NYC Health + Hospitals

In general, supportive housing uses are classified as a subcategory of community facility use known as philanthropic or non-profit institutions with sleeping accommodations (NPISA), which are allowed less density–i.e. lower floor area ratio (FAR)–than other community facility uses. The only way for supportive housing NPISA developments to achieve floor area that is afforded as-of-right to other community facility uses is through a special permit , triggering a Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP).11 ULURP can add 12-24 months to the development process, and can be costly and difficult for non-profit developers to navigate.

Methodology & Findings

In order to determine the citywide opportunity available in R5-R8 districts, we conducted a desktop GIS analysis of existing privately-owned sites and then further individually examined sites to ascertain viable sites. After our site analysis, we conducted a comparative analysis between the various types of housing that could be built on these sites today, highlighting the discrepancies between the regulations.

Soft Site Analysis

To identify a set of viable sites, we used NYC PLUTO data and culled sites based on a soft site analysis, including the following criteria:

- Site area more than 10,000 square feet

- Less than 50% available Residential, Commercial, and/or Community Facility floor area

- Within transit zones

- Near other housing

- Near services and neighborhood amenities

- Not within Landmark or Historic Districts

- No existing residential units

- Not within zones of major flood risk

- Not irregular (for example, triangular, gerrymandered, or overly narrow lots)

- No existing institutions

- No existing House of Worship on the site

Using this criteria, we identified 952 viable sites for supportive housing across R5-R8 districts.

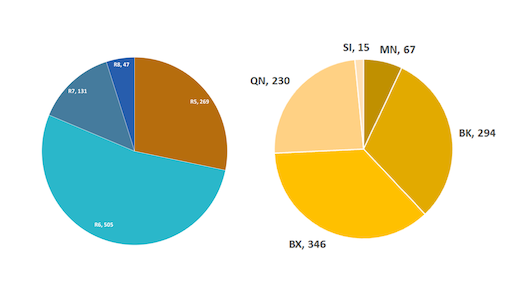

Distribution of soft sites by zoning district and borough.

Districts and Boroughs: The majority of our sites are in R6 districts primarily in Brooklyn, Bronx, and Queens.

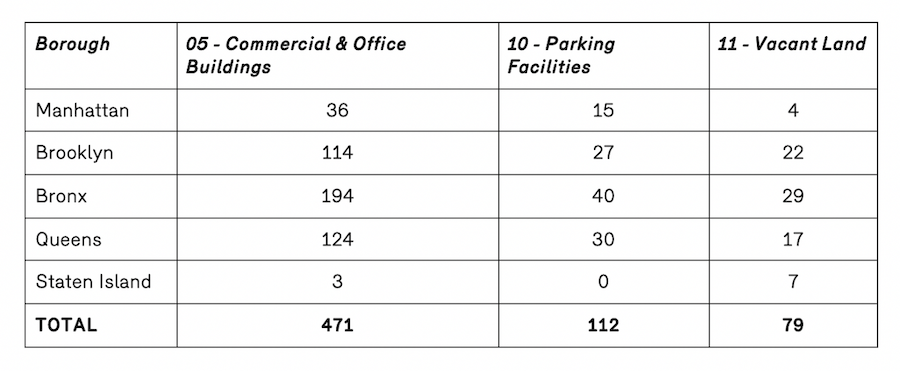

Land Use: 50% of sites (471) are commercial or office buildings, of which the majority are 1-to 2-story commercial businesses. 12% of sites (112) are parking facilities; 8% of sites (79) are vacant land.

Table 1: Distribution of Soft Sites by Land Use.

Sites with long term viability: We found 204 sites that are Houses of Worship (HoW) and decided to exclude them from our set of sites due to inherent complexities to joint ventures with HoW developments; however, with deeper investigations, these sites may offer viable opportunities. We recommend utilizing resources from community development intermediaries LISC and Enterprise to connect HoWs to supportive housing developers.

Furthermore, 9% of our sites are public facilities or institutions such as day care centers, health clinics, or community centers. These sites also offer partnership opportunities for development, but can be difficult due to ensuring the original use is not displaced, and therefore would need further analysis to determine immediate viability.

Comparative Analysis

For each district type we conducted massing studies to illustrate the differences in densities and envelope amongst the districts. We tested various mixes utilizing current regulations, including:

- As-of-right supportive housing (no permit needed)

- Senior housing utilizing the AIRS Bonus

- Affordable Housing with Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH)/Voluntary Inclusionary Housing (VIH) density bonus

- Supportive housing with the density allowed via special permit 74-903

We found that:

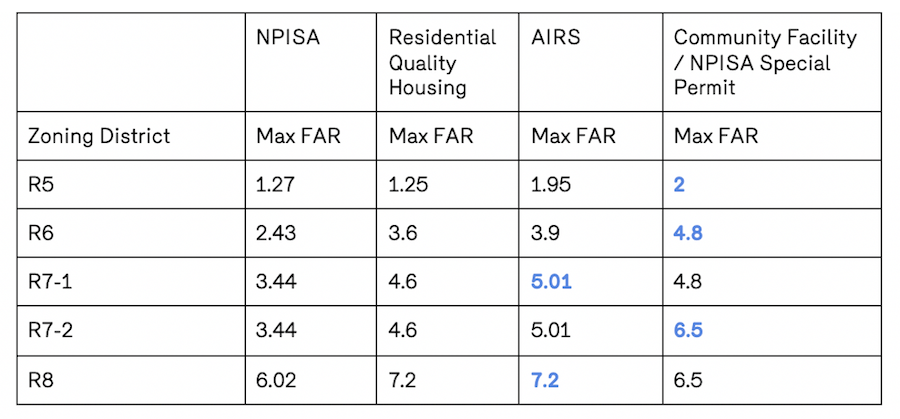

- Bulk regulations were limiting across the districts.

- While the NPISA Special Permit density was the highest in R5, R6 and R7-2 districts, the AIRS Bonus was more advantageous in R7-1 or R8 districts.

Table 2: Results of Comparative Massing Studies. NPISA pursuant to ZR 24-111(b). Residential Quality Housing FARs pursuant to the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program.

Recommendations

We believe there are several unique and parallel paths to encourage supportive housing development.

First, city agencies should foster new partnerships to better utilize public land. Innovative partnership precedents, such as the NYC H+H or the Vancouver Fire Department partnerships, have proven successful. Our soft-site analysis highlighted publicly-owned, vacant, underutilized sites where city agencies could benefit from mutual redevelopment.

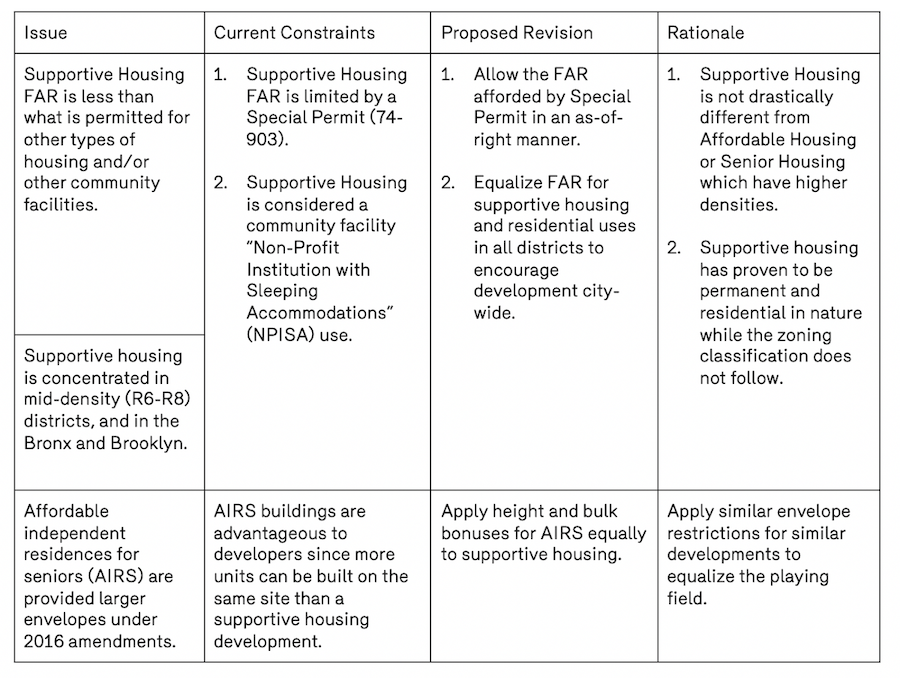

Second, the New York City Department of City Planning should amend zoning to rationalize densities across affordable building types, and right-size regulations controlling height and bulk. The changes in the table below (Table 3) will enable supportive housing development to compete on a more equal footing with other types of affordable and senior developments on privately-owned sites.

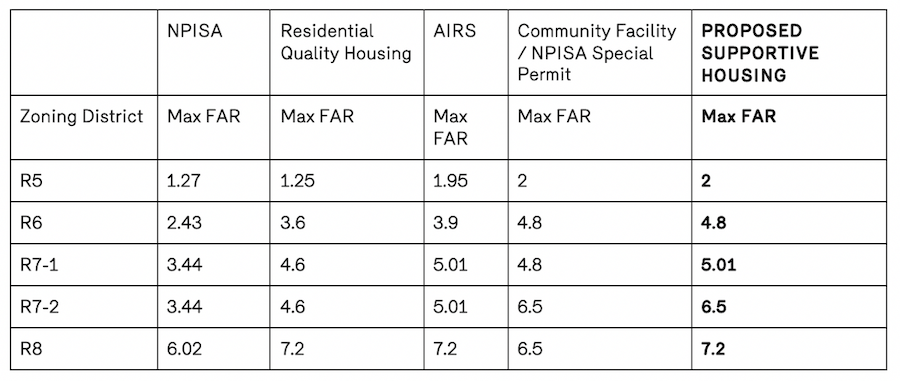

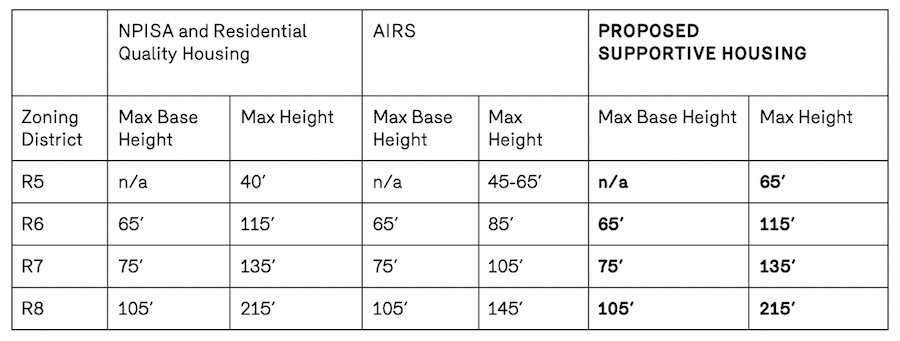

Most importantly, we recommend that the Department of City Planning revise the zoning text to apply the FAR allowable via special permit as-of-right. In practice, the permit is frequently granted to supportive housing proposals, but requires a lengthy ULURP process. Since market-rate and other affordable residential projects do not require the special permit or ULURP process, they are advantageous options for developers. Allowing a more equivalent FAR to be applied without a special permit would help supportive housing developments to be more viable options and enable more expeditious development. Table 4 below summarizes the existing and proposed FAR for supportive housing. Similarly, Table 5 summarizes the existing and proposed changes to the zoning text regarding height and bulk for supportive housing.

Table 3: Zoning Recommendations Summary.

Table 4: Existing and Proposed Max FAR for Supportive Housing. Residential Quality Housing FARs pursuant to the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program.

Table 5: Existing and Proposed Bulk Requirements. Pursuant to ZR 24-013(b)(2) NPISA may utilize Quality Housing bulk regulations, where applicable. The Base Heights and Max Heights listed are for buildings on MIH zoning lots pursuant to ZR 23-664(c)(1). Pursuant to ZR 24-664(b) for zoning lots containing 20% floor are for AIRS and building with qualifying ground floors.

These recommendations would increase the quantity of supportive housing units and speed of development, providing more housing more quickly for our vulnerable neighbors. When our zoning recommendations are applied to the 952 viable private sites, we find, on average, an increase of 78% more potential supportive housing units.

Expanding these regulations across all districts would certainly accelerate supportive housing production on private sites. Furthermore, by better utilizing publicly-owned properties and providing benefits for agencies willing to partner in development, the city can swiftly increase its own supportive housing pipeline.

Collectively, our reforms would speed up the development process for supportive housing developers, and help them to compete more equitably with other types of development. Given the imperative to address our homelessness crisis and end chronic homelessness, comprehensive policy changes such as these are necessary.

Authors ↓

Anand Amin is a Project Manager at NYCHA Real Estate, where he plans development projects that will generate +$3B for capital repairs to public housing and will create +10,000 new affordable housing units. Bringing an interdisciplinary perspective to his work, he is committed to integrating design and public policy to drive more equitable development. Prior to NYCHA, he worked in planning at the NYC Department of City Planning, in policy and advocacy at the Municipal Art Society, and in architecture at INC Architecture & Design and HDR. Anand received his Bachelor of Science degree in Architecture from Georgia Tech and went on to complete a Master of Architecture degree from the University of Michigan.

Jenneh Kaikai is Policy Advisory, Economic Development at the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Housing and Economic Development. Previously, as a Project Manager at NYCHA, Jenneh engages with NYCHA residents, community stakeholders, and private developers to facilitate affordable housing projects across NYC. With a background in Public Health, she has applied a “Health in All Policies” approach to support her interest in the need for holistic and inclusive neighborhood planning.

Andrew McIntyre is a registered architect, project manager, and Senior Associate at Robert A.M. Stern Architects. He has contributed to a range of projects including single-family homes, large-scale urban district developments, and institutional work; both domestically and abroad. Currently, he is managing the design of a multi-family supportive housing development in Brooklyn.

Catherine Nguyen is a Assistant Vice President at NYCEDC where she manages projects in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Staten Island. Catherine was previously a Green Infrastructure Planner at NYCDOT and Rebuild by Design Fellow at WXY. Catherine holds a Master of Science in City and Regional Planning from Pratt Institute.

Rebecca Sauer is the Director of Policy and Planning at the Supportive Housing Network of New York, overseeing the organization’s analysis of New York City supportive housing policies and its local advocacy efforts, as well as monitoring the implementation of the city’s commitment to create 15,000 units of supportive housing in 15 years. She has a bachelor’s in Urban Studies from Brown University and a master’s degree in Urbanization and Development from the London School of Economics.

Footnotes ↓

1. “History of Supportive Housing,” Supportive Housing Network of New York, accessed June 26, 2020, https://shnny.org/supportive-housing/what-is-supportive-housing/history-of-supportive-housing.

2. Defined by HUD as experiencing homelessness for a year or more, or four times in the last three years adding up to twelve months. (See: “Here’s What You Need to Know about HUD’s New Chronic Homelessness Definition,” National Alliance to End Homelessness,” accessed June 26, 2020, https://endhomelessness.org/heres-what-you-need-to-know-about-huds-new-chronic-homelessness-definition/.)

3. Supporting Housing Network of New York, Taking Stock of the New York/New York III Supportive Housing Agreement, https://shnny.org/uploads/ny-ny-iii-network-report.pdf.

4. HUD, 2018 AHAR: Part 1 – PIT Estimates of Homelessness in the U.S., https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/5783/2018-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us/.

5. “New York City 15/15 Supportive Housing Initiative,” NYC Human Resources Administration, accessed June 26, 2020, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/hra/help/15-15-initiative.page.

6. “Advocates Applaud Governor Cuomo’s Plan to Create 20,000 New State Funded Supportive Housing Units,” January 14, 2016, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/537e2643e4b0ef07d069369c/t/569828e9c21b86195457179f/1452812521398/SOSPressRelease.pdf.

7. Gwynne Hogan, “Brooklyn Hospital Turns Parking Lot Into Housing,” WNYC, April 3, 2019, https://www.wnyc.org/story/old-brooklyn-hospital-parking-transformed-new-homes-formerly-homeless-patients/.

8. Task Force on the United States Postal Service System, United States Postal Service: A Sustainable Path Forward, December 4, 2018, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/USPS_A_Sustainable_Path_Forward_report_12-04-2018.pdf.

9. There is additional development potential on the remaining 400 public sites that we identified; however, they would require more analysis to determine how to integrate the existing uses and a public policy commitment from agencies to build supportive housing.

10. Non-contextual districts were created by the 1961 Resolution, remain in many locations, and are designed to allow a wide range of building forms. NY Department of City Planning. Zoning Handbook. Department of City Planning, 2018.

11. Existing ZR 74-903 Special Permit allowing additional FAR for Community Facility Non-Profit Institution with Sleeping Accommodations (NPISA) use.

Header image credit: Dattner Architects