Will technology enable equitable economic development? How should technology change the way we plan for economic development?

Link to Innovation or Gentrification Express?

The New Manufacturing Sector: Made for All New Yorkers?

Link to Innovation or Gentrification Express?

A walk through Sunset Park will lead you across vestiges of old New York. Still a working industrial port and manufacturing hub, the neighborhood hearkens back to the days when New York City’s might was intertwined with the success of its shipping industry. A walk to the waterfront from the subway winds through busy commercial corridors, neat row houses, busy bus stops, and the remnants of old trolley tracks that once wound through the neighborhood, containers and cranes ever-present in the background. A home to immigrant workers, the neighborhood has shifted from Norwegian to Italian to the present day Mexican and Chinese communities that call it home.

However, as the rest of New York City changes, time is catching up with Sunset Park. New developments such as Industry City, Liberty View Industrial Plaza, the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal, Bush Terminal, the Whale Building, and the Brooklyn Army Terminal are rapidly changing the neighborhood landscape. The Brooklyn Nets own practice space in the area and West Elm and Design Within Reach each have showrooms nestled between blighted warehouses.

Sunset Park certainly isn’t an anomaly. Immigrant and working class neighborhoods across New York City are bracing themselves for speculation and gentrification. However, the neighborhood Park has received something other communities haven’t: the attention of the City. The New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC), the Department of City Planning, and the de Blasio administration have set their sights on Sunset Park as New York’s next “innovation hub”, based largely on the success of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. In a breakfast with Crain’s Business in 2016, Maria Torres Springer, the president of EDC at the time, made a promise that her agency would transform Sunset Park into a “vibrant community,” in large part by connecting the neighborhood to the city’s burgeoning tech sector. The EDC spearheaded Brooklyn Queens Connector (BQX) trolley, one of Mayor Bill DeBlasio’s most ambitious projects, promises to provide links between Astoria, Long Island City, Williamsburg, Downtown Brooklyn, and Sunset Park- and a more interconnected New York City tech sector.

New York’s tech ecosystem

New York City’s tech industry has taken off in the past few years as a result of a shift from the traditional Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate (FIRE) sector approach that has been a cornerstone of the city’s economy. In an effort to expand the tax base, the City has looked to tech as an engine of economic growth. According to an EDC official, the City has not considered a neighborhood or place based approach to tech, but rather has focused on creating a “tech ecosystem.” The BQX plays a crucial role in developing such an ecosystem by connecting neighborhoods with blossoming tech economies. Downtown Brooklyn, Long Island City, Williamsburg, and Astoria, have all seen a rise in startups and tech investment. In a nod to North Carolina’s research triangle, Downtown Brooklyn, DUMBO, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard are newly designated as the Brooklyn Tech Triangle. Williamsburg, with its booming office market, is home to an increasing number of startups and light manufacturing firms. City officials hope that Sunset Park’s industrial past will evolve into manufacturing that supports 3-D printing and biotech research.

Rendering of the Brooklyn Queens Connector (Friends of the Brooklyn Queens Connector)

EDC has expressed hope that investment in the tech sector will both expand the tax base and simultaneously create new job growth in underserved neighborhoods, spurred by the connection provided by the BQX. The trolley line has approximately 30 stops along its route, each spaced about half a mile from each other, many within the City’s new tech hubs. EDC projects that the BQX will create $25 billion in economic impact and 28,000 temporary jobs over the course of thirty years and that it will increase access to jobs for a “workforce equipped with the skills needed to participate in the 21st century economy.”

Tech: Who is it good for?

However, the question that community groups, policy advocates, and administration insiders alike are asking is: new jobs for whom? Though the BQX has received support from some local community organizations, called the Friends of the BQX, and some New York City Housing Authority residents, many Sunset Park residents along the BQX route worry that the trolley will increase speculation in an already high pressure real estate market, with little return to the community.

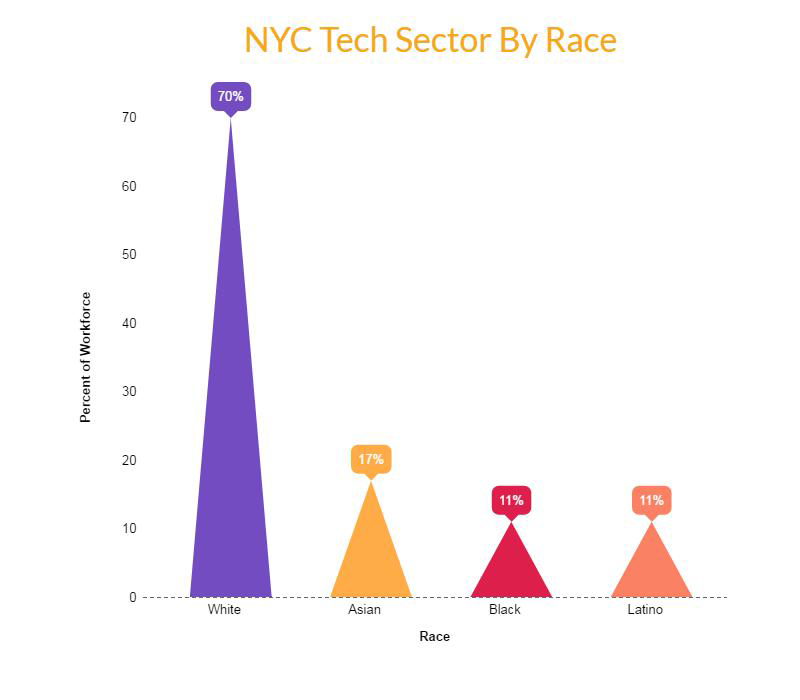

As of 2014, New York City’s tech sector was 70% White. Asians comprised 17% of the sector, while Blacks and Latinos represented only 17% and 11% respectively. Conversely, 80% of Sunset Park’s residents are nonwhite. 40% of residents are Latino while 30% are Asian. Though the average annual income of tech workers in New York City is $107,661, wages vary by race and subsector, with people of color earning substantially less than their white counterparts. Advocates worry that not only will new tech jobs be inaccessible to current residents, but once they are, that they will be the lowest paid jobs available. However, others find hope in the possibility for economic advancement through tech jobs. Christine Curella of the Mayor’s Office of Workforce Development stated that through job training, residents would be prepared not for a single opportunity, but a multitude of 21st century opportunities.

Rising property taxes, rising displacement?

Residents and advocates alike are wary that current residents will pay for the construction of the BQX and will not be able to remain in the neighborhood long enough to benefit from its purported value- whether through access to transit or to jobs. Ryan Chavez of local community group UPROSE states that though tax increment financing can be useful in certain scenarios, the model is detrimental to Sunset Park’s neighborhood economy. “When we are talking about running transit based on this mechanism through heavy industrial zones that depend on low property values to survive, the two cannot be reconciled. Industrial retention is a core concern locally and imperative to serving the economic needs of our community.” The biggest issue, however, remains the inflation of property values. Chavez continues, “Moreover, inflating property values throughout a working-class community like Sunset Park, which is already facing dramatic displacement pressures, demonstrates a callous disregard for vulnerable residents and small businesses.”

(US Census Bureau, 2014: Quarterly Workforce Indicators Data)

Estimated to cost $2.5 billion, the BQX is designed to be “self-financed”. A departure from traditional municipal bonds, the BQX financing depends on rising property taxes. Increase in property taxes as a result of a rise in property value along the streetcar routes will be captured to pay for the cost of the project. The BQX’s success is dependent on the creation and preservation of new, high cost real estate.

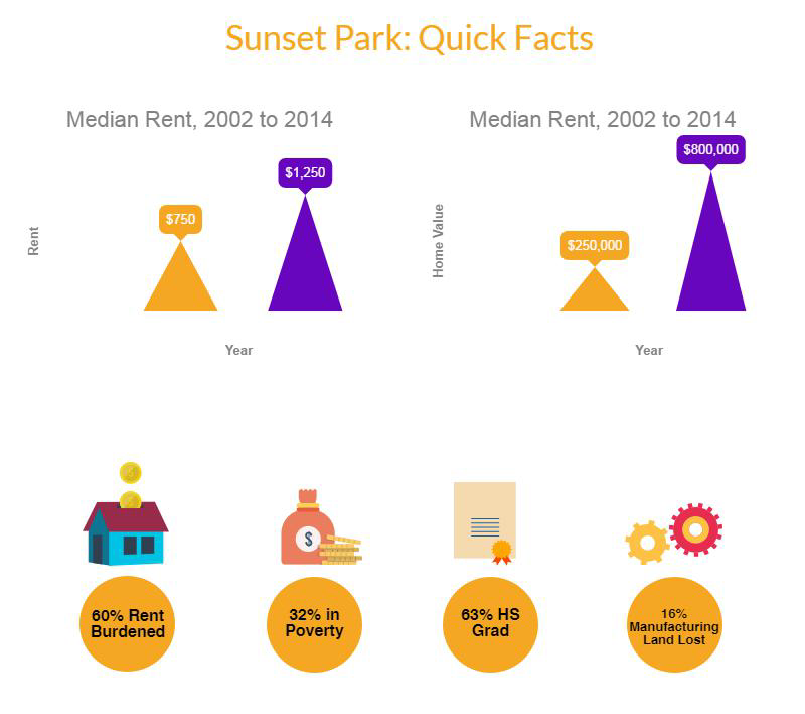

This exacerbates community concern that the creation of BQX will not be of use to current residents. In a community where a quarter of residents are homeowners, a steep rise in property taxes can be untenable and ultimately lead to displacement. While the full borough of Brooklyn has seen skyrocketing property values, speculation in Sunset Park has been slower- until the past few years. Between 2002 and 2014, median home values rose by 31%, from $250,000 to $800,000 and median monthly rent rose from $750 to $1,255 in the same time period. And the neighborhood’s demographics have slowly changed as well.

In a neighborhood with limited rent regulated housing stock and 60% of residents already rent burdened, the prospect of an influx of luxury condominiums and increased housing costs is disconcerting.

According to the Furman Center, average median income rose 4.7% between 2010 and 2014; however, the poverty rate also rose risen slightly, with 32% of the population living in poverty. Residents and advocates alike are wary that current residents will pay for the construction of the BQX and will not be able to remain in the neighborhood long enough to benefit from its purported value- whether through access to transit or to jobs.

BQX and business

Residents aren’t the only ones concerned about the BQX route. Industrial and manufacturing businesses, which employ 12% of Sunset Park residents worry about tech-focused light manufacturing displacing traditional manufacturing. Changing land use, shifting commercial corridors and streetscapes, and an increase in price per square foot of already expensive M-zone land is a cause for concern for many industrial businesses who already struggle to pay operating costs. And, in a rapidly shifting sector where work happens less on the factory floor, and more on a computer in an office building, advocates of traditional industrial and manufacturing jobs worry about the change from M-zoned land to include office space, creating more competition for already scarce land.

Some transit officials are also skeptical of the utility of the streetcar in a neighborhood like Sunset Park, especially during the construction phase which is anticipated to inhibit trucking and transport- vital components of the manufacturing adjacent industries. A New York City Department of Transportation official who asked to remain anonymous stated: “This is a real estate tool. There is no real transportation value to it. I don’t see how manufacturing businesses will benefit from this project.”

(Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development)

Industrial and manufacturing businesses are also concerned about the displacement of their employees. As the largest walk-to-work community in the country, Sunset Park’s economy is dependent on its residents. Andrea Devening of Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Development Corporation (SBDIC), an industrial business service provider, noted that displacement of residents is an ongoing concern, as is matching businesses with workers with the skill set and experience needed for industrial jobs. SBIDC works with the City’s Workforce1 Career Centers to connect residents with manufacturing jobs.

Manufacturing jobs have traditionally provided avenues for economic opportunity for those with limited access to educational advancement, particularly newly arrived immigrants and communities of color. The industrial and manufacturing sector pays double the average wages of a sector with comparable educational requirements, such as retail. However, the number of available manufacturing jobs is limited, and the changing face of the manufacturing sector has shifted the sector toward more high skilled jobs. Businesses and community members worry that the impact of the BQX and a focus on tech will indeed create employment opportunity- but opportunity that is unattainable to current residents and displaces existing manufacturing jobs.

Creating equitable transit

In order for the BQX to be successful, it must take particular neighborhood needs into account. Sunset Park’s needs are very different from those of DUMBO. And, in order for the City’s vision for an equitable economy fueled by the tech sector to be possible, significant resources must be invested not only into the neighborhood’s physical landscape, but also its people. A tech ecosystem will do little to benefit current Sunset Park residents if they can no longer live or work in their neighborhood. Significant funding for job training, placement, and workforce development is crucial to ensuring that the BQX doesn’t live up to its sobriquet as “the Gentrification Express.”

The New Manufacturing Sector: Made for All New Yorkers?

Industrial job creation and retention has become a focal point in public policy both locally and nationally. The manufacturing sector has provided steady, well-paying opportunities and a clear path for socioeconomic mobility for over a century in the United States. However, as our society modernizes and continues to embrace globalization and technological development, traditional manufacturing jobs are decreasing. Nowhere is this trend more apparent than in New York City, where there is intense competition for physical space to develop industry, commerce, and housing. The boom in land values has driven a surge in luxury housing and commercial development with disparate impacts on residents and employees. In order to promote equitable development, the City must harness its toolbox to capitalize on growth in the technology and advanced manufacturing sectors to provide quality manufacturing jobs to a wide array of New Yorkers.

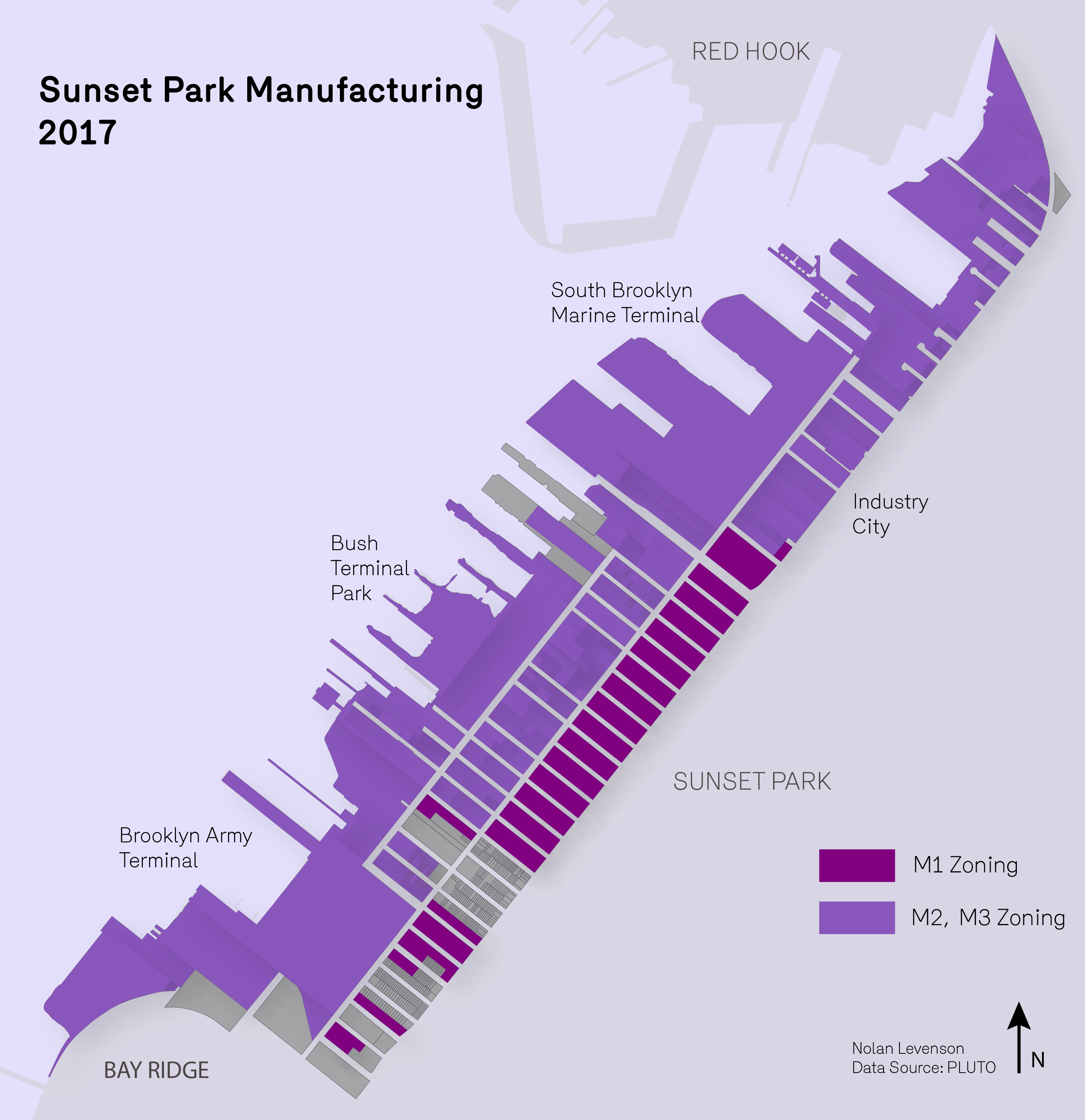

In recent years, housing and commercial development has been encouraged through zoning. Under Mayor Bloomberg, the Department of City Planning rezoned a number of industrial areas that became real estate hot spots, such as the Williamsburg waterfront. Between 2002 and 2007, the Department of City Planning rezoned close to 1,800 acres of manufacturing-zoned land—approximately 15% of the entire citywide stock (1). In addition, the existing zoning code does not protect manufacturing uses even in industrial areas. Only 3.5% of the city’s total lot area is used for job-intensive manufacturing despite the fact that manufacturing zones account for 14.1% of the city’s total lot area (2). Non-industrial uses are still permitted in manufacturing zones, driving up the value of land for more lucrative uses such as hotels, storage, and night clubs (3). Figure 1 shows the types of uses permitted in these zones.

92% of the Sunset Park waterfront lot area is zoned for manufacturing.

Sunset Park, Brooklyn is at the forefront of this pressure on manufacturing land. Its waterfront is one of the few remaining manufacturing areas in New York City, abutted by a primarily minority-majority neighborhood with large immigrant populations that is rapidly gentrifying. 47% of the population is foreign born, and 72% of the population is Hispanic or Asian (4). Increasing rents and development pressure is putting a significant burden on the neighborhood’s population. In addition, unlike many other neighborhoods, Sunset Park residents rely heavily on job opportunities within their community. 20% of residents walk to work, including the waterfront area that has numerous industrial jobs (5).

The Sunset Park waterfront is part the Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Business Zone (IBZ), which was created to protect and promote industrial growth. Despite the IBZ designation, industrial jobs have declined over time on the Sunset Park waterfront (defined as the waterfront area bound by the Gowanus Canal, Gowanus Expressway, and Belt Parkway). In 2002, there were 8,452 jobs in industrial sectors (manufacturing, wholesale trade, and transportation and warehousing) representing 36.5% of all jobs in the area. In 2014 there were only 6,771 (representing 30.1% of all jobs in the area), a decrease of 19.9% compared to a 5% total job loss in the area between 2002 and 2014 (6). Existing zoning does not prevent developers from creating non-industrial uses in Sunset Park. According to PLUTO data, 92.4% of the lot area is zoned for manufacturing, however 80% of the existing land is used for Industrial, Manufacturing, Transportation, and Utility uses, highlighting the flaws in the zoning code. Of the manufacturing zoned land, 12% of the lot area has an M1 zoning designation, which as previously noted allows for the widest array of uses that drive up land values, making industrial uses financially untenable. This puts industrial development and jobs at risk.

2 Av & 41 St: A typical block in Sunset Park, Brooklyn (Nolan Levenson)

While there has been overall job loss on the Sunset Park waterfront, numerous industries have seen increases in recent years. Between 2005 and 2014, commercial uses in the Southwest Brooklyn IBZ more than doubled with an increase of over 2.3 million square feet, an increase of 155% (7). These numbers are indicative of the new wave of non-industrial development that has surged both in Sunset Park and citywide, in particular the significant increase in retail and the tech-related sectors of “Information” and “Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services.” (see Figure 4). Some critical questions should be asked about who benefits from this growth and at what cost to others. Is this economic development equitable, particularly for longtime residents of New York City and specifically Sunset Park?

Many Sunset Park residents, 29% of which live below the poverty line are effectively excluded from both the consumer and economic development benefits of this growth (8). One of the most successful new employers in the area has been Industry City, which is a thriving commercial area focused on the technology, advanced manufacturing, and luxury commercial sectors. Its featured tenants include Design Within Reach, the Brooklyn Nets, Bauble Bar, and West Elm. A recent New York Times article featured the Extraction Lab, where the manufacturer of a high-end coffee machine called “Steampunk” charges up to $14.75 for a cup of coffee (9, 10). These new businesses are generally looking for college-educated and highly skilled labor—a trend seen around the country (11). In Sunset Park, however, 42% of residents have not completed high school and only 29% have graduated college, making it very difficult to obtain quality jobs in Industry City (12).

1st Avenue- Sunset Park (Nolan Levenson)

Many local stakeholders fear that the new wave growth will exacerbate gentrification in Sunset Park. As industrial jobs are replaced by opportunities in tech-oriented, advanced manufacturing, and retail sectors, the amount of quality, well-paying opportunities for low skill minority workers decreases. On average, in Brooklyn and Queens, industrial jobs pay an average of $50,934, about twice the average salary of $25,416 in the retail, hotel, and restaurant sectors (13). In addition, over 80% of industrial workers are from populations of color (14).” This change in opportunities directly impacts many residents of Sunset Park, of which 55% are already rent burdened (15).

A number of organizations are working to mitigate some of these issues by preserving manufacturing jobs in Sunset Park, including the Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Development Corporation (SBIDC), which promotes economic development by serving small businesses and residents. SBIDC’s services include workforce development, where they work with local businesses to understand their operations and training needs. Through this program, typically 100 job-seekers are placed each year into quality manufacturing and transportation jobs. In April 2016, through grant funding from the City, they expanded to operate the Brooklyn Workforce 1 Industrial and Transportation Career Center located in the Brooklyn Army Terminal (BAT). They now can serve 250 job seekers annually. Industry City has also launched a program to provide training and education for local residents called the Innovation Lab. The program is relatively new, however, and the impact has yet to be seen (16).

The City must have a major role in ensuring that the new tech-oriented and advanced manufacturing development in Sunset Park is equitable. The City is the primary landowner on the Sunset Park waterfront (47.2% according to PLUTO data), including the 97-acre BAT, which gives the City’s Economic Development Corporation broad control of the kinds of development that will occur in Sunset Park. Recently, Mayor de Blasio announced a $136 million investment in Bush Terminal to create the “Made in New York Campus” designed to help “synergize creative manufacturing uses.” The campus will primarily house space for garment manufacturing and film and media production (17).

However, if there is truly a commitment to industrial development and jobs, the City must work to change zoning regulations in Sunset Park to ensure that manufacturing uses are central in development. It should learn from previous experiences in waterfront manufacturing areas such as Williamsburg and Greenpoint, where lax manufacturing zoning has encouraged a spur in hotel, retail, residential, and office development. Non-industrial uses such as hotels and storage should require special permits rather than allowing these uses as-of-right. In conjunction with existing workforce development programs, the City should leverage its powerful position to incentivize industry that provides a wide array of employment and training opportunities. It must require that manufacturing uses can thrive in Sunset Park and throughout the city.

References

1,2. New York City Council. “Engines of Opportunity: Reinvigorating New York City’s Manufacturing Zones for the 21st Century.” November 2014.

3. Chapelliquen, Armando. “Enhanced Business Areas & 25 Kent: NYC’s Commercial / Industrial Zoning Proposal.” Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development. March 2016.

4. NYC Health Department. “Brooklyn Community District 7: Sunset Park.” Community Health Profiles: 2015. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2015chp-bk7.pdf

5. NYCEDC. “Sunset Park Waterfront Vision Plan.” 2009. https://bit.ly/2oCtIwu

6. US Census Bureau. Center for Economic Studies.

7. New York City Council. “Engines of Opportunity: Reinvigorating New York City’s Manufacturing Zones for the 21st Century.” November 2014.

8. NYC Health Department. “Brooklyn Community District 7: Sunset Park.” Community Health Profiles: 2015. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2015chp-bk7.pdf

9. Fabriacnt, Florence. “A Coffee Shop That Doubles as a High-End Coffeemaker Showroom.” New York Times. January 30, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/30/dining/coffeemaker-extraction-lab-alpha-dominche-brooklyn.html

10. Santore, John V. “Sunset Park’s ‘Extraction Lab’ Is Serving A $14 Cup of Coffee—And Normal Cups, Too.” Sunset Park Patch. February 6, 2017.https://patch.com/new-york/sunset-park/sunset-parks-extraction-lab-serving-14-cup-coffee-normal-cups-too

11. Selingo, Jeffrey. “Wanted: Factory Workers, Degrees Required.” New York Times. January 30, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/13/nyregion/mayor-de-blasio-new-york-state-of-city-address.html

12. NYC Health Department. “Brooklyn Community District 7: Sunset Park.” Community Health Profiles: 2015. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2015chp-bk7.pdf

13. New York City Council. “Engines of Opportunity: Reinvigorating New York City’s Manufacturing Zones for the 21st Century.” November 2014.

14. Chapelliquen, Armando. “Enhanced Business Areas & 25 Kent: NYC’s Commercial / Industrial Zoning Proposal.” Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development. March 2016.

15. NYC Health Department. “Brooklyn Community District 7: Sunset Park.” Community Health Profiles: 2015. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/data/2015chp-bk7.pdf

16. Industry City Innovation Lab. https://industrycity.com/innovation-lab/

17. New York City Economic Development Corporation. “The Made in NY Campus at Bush Terminal.” https://www.nycedc.com/project/made-ny-campus-bush-terminal

Will the Era of Automation Establish a New Living Wage?

Since at least the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and the Trump election in the US, it has become clear that the increasing economic and social inequality experienced in these countries also has political consequences. If we want to save the state of our democracies, we need to find ways of stabilizing our economies and provide everyone with a decent economic basis for living.

Technology is often seen as a solution to the economic and social issues of today. The tech sector has added 45,000 jobs between 2003 and 2013 in New York City alone and is celebrated for the potential to provide new middle income jobs (HR&A, n.d.). It has however also created the displacement of jobs. Machines, or the automation of production processes, have replaced over 80% of jobs in manufacturing across the U.S. (Hicks and Devaraj, 2015). While some economists (Lewis, 2016) argue that technological advancements always shifted jobs to other, more work-intensive jobs, other economists (Armellini and Pike, 2017) warn that the development of robotics and artificial intelligence might lead to the displacement (without replacement) of millions of jobs. Thus, a question that we need to ask is, will technology enable equitable economic development or endanger the social and economic paradigm of our society?

In this essay, I look at how technology changed the social and economic fabric of a New York neighborhood, Sunset Park, and argue that for technology to enable an equitable economic and social outcome for all, we need to fundamentally rethink how we recuperate the collective production of wealth as a society. The universal basic income is one way we can start to think about achieving this goal. Are cities the place to test these policies first?

Technology and job creation

Questions around how many jobs and which ones will be replaced by technological advancement in robotics and artificial intelligence has become a major focus for research. A report by McKinsey analyzes work activities by their potential for automation and shows that “currently demonstrated technologies could automate 45 percent of the activities people are paid to perform.” For work activities in predictable physical environments, such as activities in manufacturing, food service and accommodation, and retailing, this number is even higher at 78% (Chui et al., 2016). Least susceptible to automation, at least with currently available technologies, are activities like managing others, applying expertise, and stakeholder interactions – all mostly high-skilled activities. With advancement in the field of artificial intelligence, more activities will be replaceable by robots. Well-known examples include the redundancy of taxi drivers in an era of autonomous vehicles or the replacement of translators by computers.

While technology and automation will make the economy as such richer, it will reinforce the economic and social inequalities we already see today.

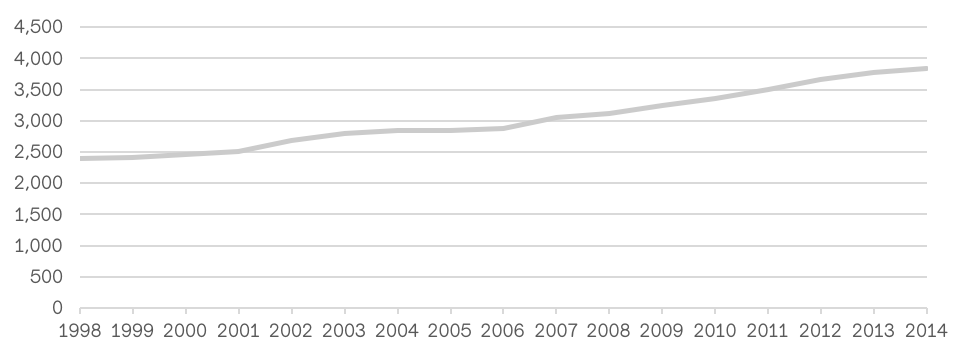

Technological advancement however also led to new job creation. The technology sector, defined here as companies that manufacture hardware, develop software, and provide services related to information technology has created thousands of jobs that were non-existent even just a decade ago. Moreover, technology has enabled new forms of advanced manufacturing. There is an increase in companies making specialty products using new technologies such as 3D printing. These companies cater to a consumer base that is willing to pay premium prices for custom made artisanal products. The Center for an Urban Future states in a recent report that New York City’s manufacturing sector has grown by 3,900 jobs in the last five years (Center for an Urban Future, 2016). Technology has also increased spending power – at least among some of us. As technology substitutes labor, consumer prices decrease. As a consequence, people have more expendable income, boosting leisure spending at salons, coffee shops, or cosmetic surgery (Deloitte, 2015).

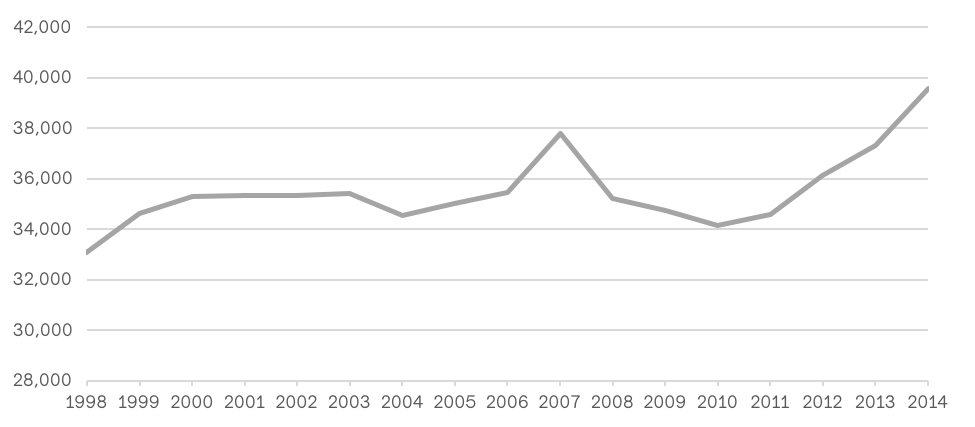

Number of business establishments across all sectors in Sunset Park (zip codes 11220 and 11232) Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Researchers do not agree on the question if jobs are created or lost. However, they generally agree that automation replaces or decreases the wages of low-skilled labor and creates new jobs for high skilled labor, widening the income gap further (see, for example, Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2016). In this scheme, as unemployment drives down wages, labor becomes more competitive again compared to the capital costs for introducing robots. What does this mean for an urban neighborhood whose employment basis was traditionally in manufacturing?

Sunset Park’s economy: From manufacturing to retail

Sunset Park in Brooklyn began to grow at the end of the 19th century when New York’s harbor became increasingly important for the import and export of goods. The industrial waterfront was dominated by the Industry City built in the 1890s as an intermodal shipping, warehousing, and manufacturing site and the Brooklyn Army Terminal built in 1919 as a warehousing and shipping terminal (and the largest military supply base during World War II). The construction of the elevated Gowanus Parkway and white flight contributed to a population decline in the 1940s and 1950s. In the 1980s and 1990s, the neighborhood was growing once again with new immigrants populating the area. It continues to grow today, not only in population, but also in employment. The graph below show the growth of business establishments as well as jobs (except for the post financial crisis dip) over the past fifteen years. How equitable is this growth for residents of Sunset Park? Does technology play a major role?

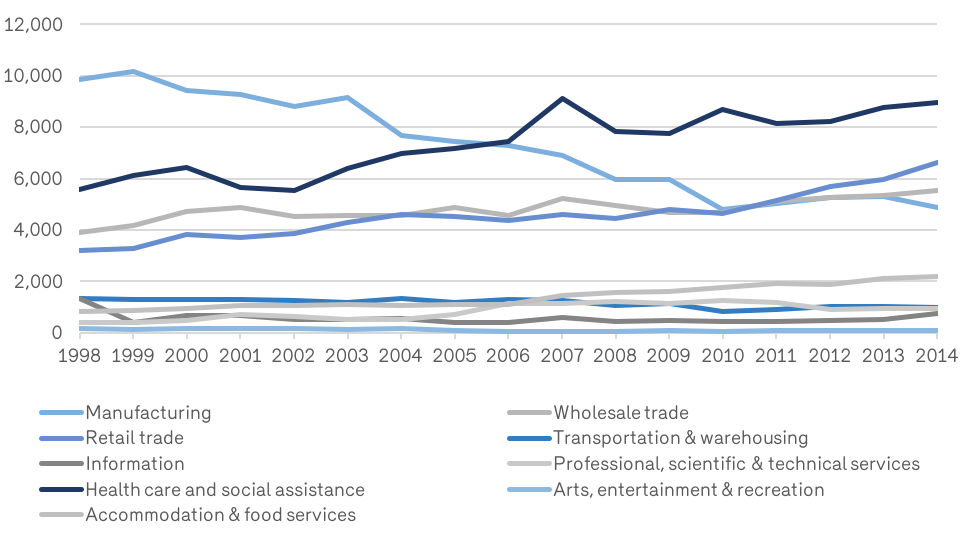

Number of paid employees across all sectors in Sunset Park (zip codes 11220 and 11232) Source: U.S. Census Bureau

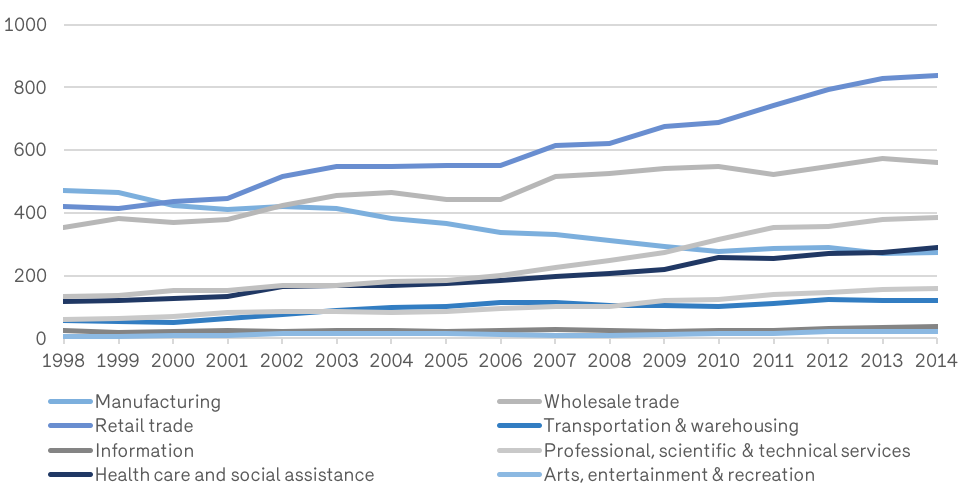

Looking at those sectors that are most directly affected by technological advancement, we see that the number of manufacturing businesses (see Figure 3) declined while the number of business establishments in other sectors increased, most drastically in the retail and wholesale sectors. Employment data (see Figure 4) provides a similar picture. The number of paid employees in manufacturing has significantly decreased over the past 15 years whereas employment in almost every other sector has grown. Looking at the type of establishments in the manufacturing sector back in 1998, the sector was dominated by food and apparel establishments. Interestingly, this has not significantly changed. There seems to be a lot more diversity in the manufacturing sector, but food and apparel still constitute the majority of manufacturing businesses in Sunset Park.

The retail and accommodation and food services sectors have seen significant growth in the number of establishments, but not as much in employment growth. This could be an indication that while new businesses open, there are less jobs needed due to automation, confirming the argument that automation with currently established technologies is most able to replace manufacturing, retail, and accommodation and food services jobs. At the same time, the health care and social assistance sector has seen significant growth, in both the number of established businesses as well as paid employees.

Number of Sunset Park business establishments according to sector. Source: U.S. Census Bureau. Note: The U.S. Census Bureau’s NAIC codes do not include a specific tech sector, but have technology-based jobs in all sectors. Nevertheless, it was regarded sufficiently illustrative to use these aggregate sectors.

Industrial Business Zone: Saving manufacturing

The New York City government is committed to preserving manufacturing in Sunset Park. The neighborhood is in the Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Business Zone (IBZ), is one of sixteen IBZs created by the New York City Economic Development Corporation to “foster industrial sector growth by creating real estate certainty” (NYCEDC, n.d.), meaning that these areas will not be rezoned for other uses and are supported by tax credits. However, the IBZ designation is already under much pressure as there is a rezoning plan for the Industry City area that would allow for integration of retail and two hotels. In addition to the IBZ designation, the City has made significant investments in Sunset Park, ranging from rail upgrades and open space improvements to capital improvements on city-owned industrial assets such as the Brooklyn Army Terminal.

Industry City as well as the Brooklyn Army Terminal are celebrated as new hubs for (advanced) manufacturing. In order to provide jobs to the community (and potentially those who lost their traditional manufacturing jobs), both have educational and training programs. The Innovation Lab at Industry City offers training such as computer classes and is adamant about filling its job with local residents (Interview with SBIDC). The Workforce1 Industrial and Transportation Career (ITC) Center at the Brooklyn Army Terminal offers “candidate and recruitment services responsive to the needs of local residents, including career planning, job search, training and employment support” (NYC Office of the Mayor, 2016).

Number of paid employees in Sunset Park according to sectors Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Note: The U.S. Census Bureau does not publish employment data for zip codes, the above numbers are thus an estimate based on the number of businesses for each employment range.

These initiatives certainly have a positive effect on the local economy. As the data however shows, these jobs have – at least so far – not been able to replace the number of jobs lost in the traditional manufacturing sector and with increasing automation, it is unclear if those lost jobs will ever be replaced. This raises the question if we need to find other ways of supporting those who will lose their jobs due to automation and will not have the capabilities to be re-trained for the types of jobs required in an era of automation.

Rethinking our economic and social policy: A radical suggestion

Today’s economic development policies include lower real estate rents or tax credits to private enterprises in order to lure businesses to priority neighborhoods. This approach helps to revitalize neighborhoods and even provide new jobs. These policies however often have uneven outcomes: While some firms and individuals profit, others do not and – in some cases – even suffer higher costs due to gentrification. With automation and the consequential loss of jobs, the inequality of wealth will likely be even more pronounced.

It might therefore be time to rethink our economic and social policies and shift from a system where the collective production of wealth is privately appropriated towards a system where the collective production of wealth is also collectively appropriated as a dividend that goes to each individual (Varoufakis, 2016). Several communities across the world are starting to experiment with a universal basic income where every citizen receives an income to live on. This would not only reduce the stigma to those becoming unemployed due to automation, but would also stabilize aggregate demand for our economy.

Sunset Park, a neighborhood that is seen as being at the forefront of the technological changes in manufacturing might also be a good testbed for new social and economic policies such as the basic income.