For this month’s Fellow Spotlight, we spoke with Siqi Zhu an NYC-based urban planner and technologist working across technology incubation, human-centered design, and the built environment.

Below, we talk with Siqi about the possibilities and challenges of urban technology and the role it plays in our cities.

You work in this interesting intersection between urban tech and design. How did your interest in these two worlds first develop?

SZ: I went to grad school to study urban planning over 10 years ago. The whole notion of urban technology was nascent, but I became very interested in various data-driven ways of seeing our cities. Even though there weren’t words for it, spatial analytics and data visualization was what sparked my interest. As I was growing my career as an urban planner and designer in the more traditional vein, I was also cultivating these interests. Then, I took a job leading product design at a computational design software company called Envelope.city and it felt like these two worlds started to come together. At Sidewalk Labs, I was able to define a lot of my work at this intersection. I would say the work of Delve is very contiguous with that interest because it combines the analysis of data and urban development in one software.

Can you tell me a little bit about your day-to-day at Delve?

SZ: I started fairly recently at Delve. Delve is a computational tool that can rapidly generate many design options based on the specific constraints and inputs of a real estate development project. I manage Delve external engagements and work with real estate developers, design firms and sometimes cities to apply Delve as a tool and methodology to solve the key core problems of their projects.

You’ve also been teaching throughout your career. Tell me a bit about the program at Harvard that you currently teach at.

SZ: I’m an adjunct professor at the Master of Design Engineering program, which sits between the Graduate School of Design and the engineering school at Harvard. The program challenges students to think about how to design future systems and technologies. So, not just buildings and landscapes, but all sorts of digital, physical and social technologies that shape our future society. We provide students with a thematic “umbrella”–like decarbonization, for example–and they have to come up with an intervention that positively impacts society in a way that’s consistent with this theme. Whether that is to design a form of public institution or civic infrastructure or a particular technology, is really up to them.

How do you see urban planning and design changing as technology evolves?

SZ: I have some mild dissatisfaction about the roles that architects and urban planners are relegated to. We are dealing with some really big societal issues and I think our architects and planners are often asked to think about them within fairly prescribed boundaries. We can design buildings that are more energy-efficient and districts that are more flood resilient, and that’s extremely important. But, I also think the most interesting work can happen when we see people break out of their discipline and are able to work at the scale of institutions and systems, whether digital or social–that’s the level that I hope we are training people on.

It’d be great if every profession encouraged us like this!

SZ: Yeah, but it’s a bit of a double-edged sword, right? You want students to have the right kind of strategic design chops and intellectual versatility, but you also want them to be really good at a discipline. Architecture and planning have a disciplinary core and as a teacher you need to make sure students have that.

What urban technologies might we expect to see in our future cities?

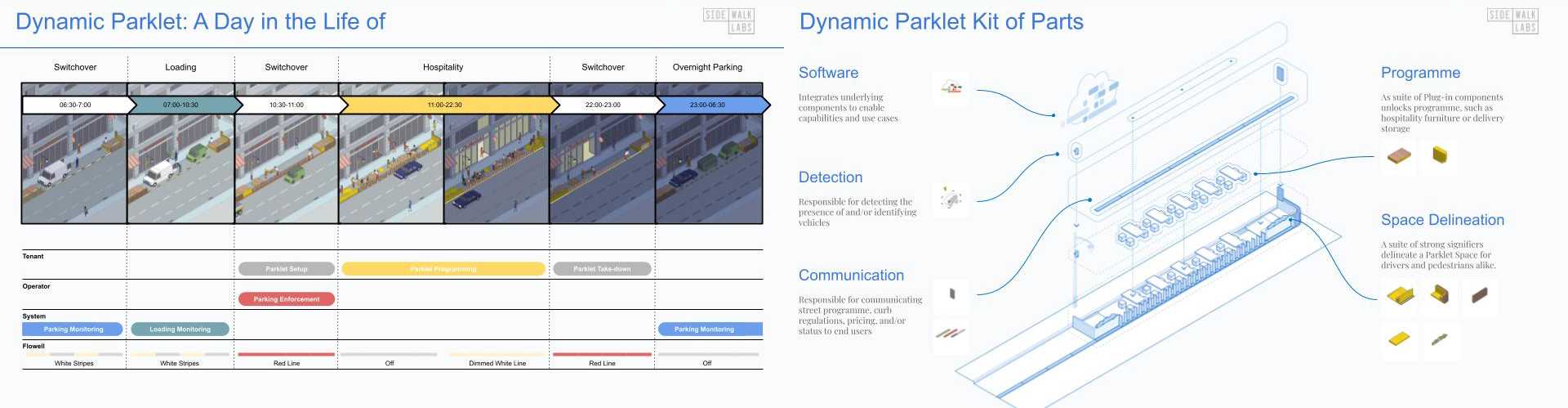

SZ: Notwithstanding its many political difficulties, the reality of an urban environment as a “smart environment” is only going to evolve and grow. Last year, I was working on the idea of streetlights as a platform for collective urban intelligence. We know that police departments and DOTs already put a lot of sensors on street lights, but what if this intelligence can be opened up to a wider array of stakeholders? What kind of collective capacity does that create for ordinary citizens?

We are also probably going to co-inhabit the city with different forms of robotic intelligence in cities. Maybe not fully autonomous self-driving cars, but probably some kind of autonomous delivery. For example, the architect Greg Lynn has been developing carrier robotics the size of vacuum cleaners. Fairly soon, I imagine we’ll need to negotiate rules on co-inhabiting public spaces with these robotic forms. What are the rules and regulations for that? There’s a future that could be very good and another that can be disastrous.

I also think technologies for energy and climate resilience are going to increasingly manifest in the public realm, especially electrification infrastructure. We’re going to have to build a whole lot of new EV charging infrastructure and that’s going to change some of our habits in the public realm. So, how do we not give up these public realm spaces to charging infrastructure? Maybe it’s about using that infrastructure as an opportunity to create other forms of social life on our streets. Again, these technologies as they’re rolling out can bring both a good and bad future. We don’t really know, but it’s incumbent on us urbanists to shape that future.

What challenges might cities face concerning new urban technology?

SZ: The typical approach that city agencies take is to create a time-bound and space-bound “zone of exception” around pilot implementations of new technologies. This has worked in some cases, but less so in others and it doesn’t always lead to wider adoption.

I do think knowledge- and experience- sharing within the urban technology community is important. If it’s working in one city, it probably has a higher chance of working in other places. Continuing to share experience and knowledge across places is important, and a lot of folks are already doing that. Also, like the Master of Design Engineering program, it might also entail training people to converse on multiple sets of issues so as they join the workforce, they can play more of an advocacy role.

Also, cities are talking about the need for innovation a lot. But, you can often find hesitancy from the parts of city government that are potentially responsible for the day-to-day operations and maintenance of new technologies. That’s one reason why certain innovations can’t gain traction as quickly as they would in a consumer market. It’s easy to get everybody to buy the next generation of electric toothbrushes, but far more difficult to convince a city to accept all the responsibilities that come with maintaining a new type of pavement. The private sector has a role, but the challenge is that you need public sector and community buy-in.

Anything you want to share with the Urban Design Forum community?

SZ: Oftentimes when we talk about urban technology, we automatically think about cutting-edge technologies like AI-driven robots, but the more interesting story that’s actually relevant to urbanists is how technologies gain permission through our political and institutional processes and how they are implemented, upgraded, and maintained. These are the capacities we need today, even more than capital R R&D.

What I’m interested to know is, how does the urbanist community play a role in building that capacity? It’s part of what motivates my longer term thinking about this work and it’s something I’m curious to hear about from the Urban Design Forum community.

Siqi Zhu is currently Program Manager at Delve @ Google, a computational tool for sustainable urban development. Previously, he was a Director of Planning at Sidewalk Labs, where he provided urban innovation consulting to the development industry, led a technology development program focused on “streets of the future”, and oversaw key aspects of the Quayside project. Prior to Sidewalk Labs, he led the product function at Envelope.city and managed urban development projects at Boston-based Sasaki and Utile. He is also an active educator and design researcher, and his interests focus on the legibility and governance of contemporary cyber-physical technologies; technology controversies and technology counterfactuals; and new roles and competencies for the design professions.

This conversation is the third of our Reconnect Conversations focused on building community at the Forum through interviews, events, and gatherings for our Fellows. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarification purposes.