The Urban Design Forum’s 2018 Forefront Fellowship, Shelter for All, addressed the homelessness crisis in New York City by examining how to dignify the shelter system through better design and exploring the root causes of homelessness and housing precarity. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on how to address the prison-to-shelter pipeline, public bathrooms, public realm management, supportive housing, and racist housing policies, which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

The following interview with Graham Ciraulo, a tenant leader with the Metropolitan Council on Housing, accompanies Systemic Radical Change. Read the full set of Shelter for All proposals and interviews here.

Nova Lucero: Can you tell us how you got involved in organizing with the Met Council on Housing?

Graham Ciraulo: I moved to Inwood basically out of emergency. I was able to find something in Inwood that happened to be rent-stabilized, just by chance.

I was at a church, the Good Shepherd in Inwood, and the priest said at the end of the mass, “The neighborhood is being rezoned, and there is a meeting about it. You should all go.” This is in 2015. And when I hear rezoning, I know exactly what they’re going to do. I went, and that’s when I first really got a taste of the EDC and how they treat people in the community.

Inwood is still largely a Latino community, a lot of the longtime residents, and those are the people who show up to these meetings. The EDC people were just so disrespectful. They had never been up to Inwood before. They were just kind of wonky urban planners, and they were talking down to everybody. They were like, “Well, what do you want? What do you all want? What do you want?”

And people would say, “Well, we like the low-rise buildings.”

“Yeah, but don’t you like this? What about this esplanade?” And they showed these shiny projects, like, “Don’t you want this?”

People would try to talk about the real problems in the community. And the EDC representative would just be like, “Okay, okay.” I was distressed by it. At the end, someone said, “We like our neighborhood the way it is.” And the EDC representative said, “Well, I know it’s really nice, but you know, it can’t stay like this forever,” or something like that. I was just enraged.

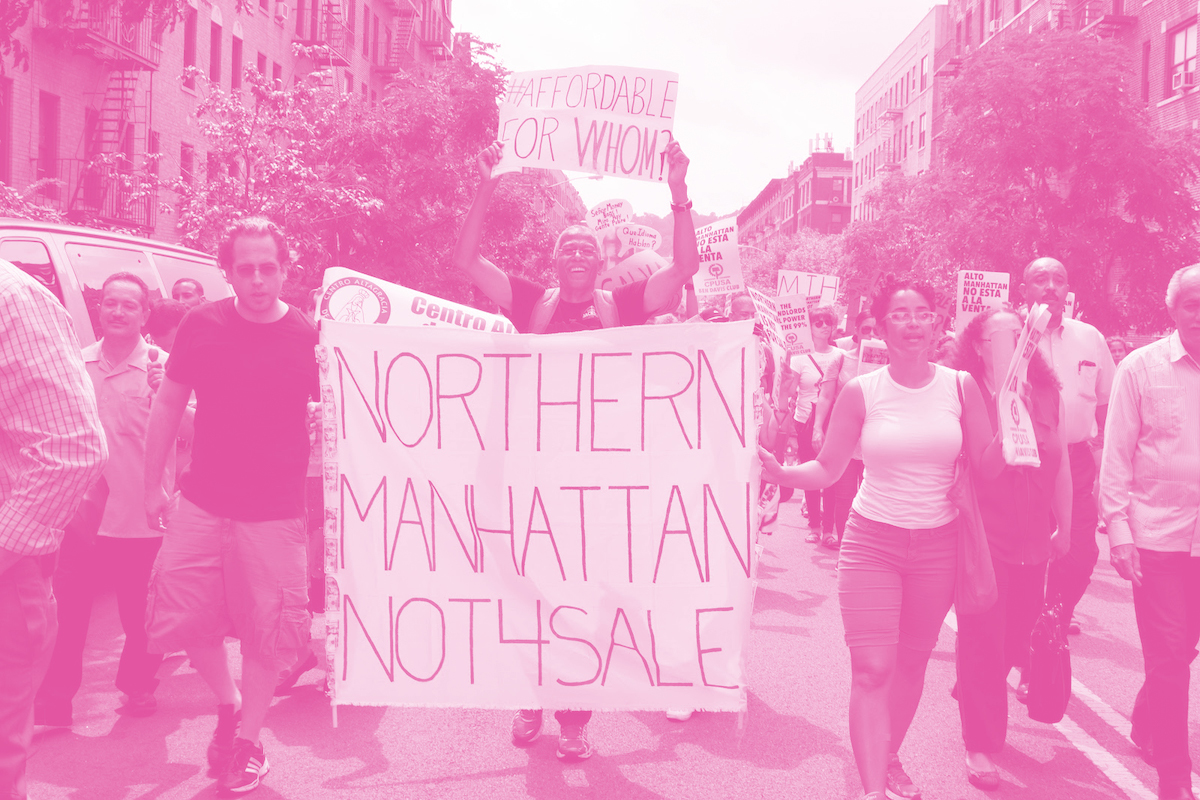

Residents fight for affordable housing in Inwood. Image credit: Nova Lucero.

Somebody handed me a flyer from the Met Council on Housing about an emergency meeting, that says, “Fight back.” And I said, “I’m going to this!” That’s when I went to my first Met Council meeting. Everybody there helped me get involved in organizing, and I just learned so much.

Emma Silverblatt: I wanted to ask you about something that the EDC person said to you, that it can’t stay that way forever. What is your response to that working in housing? Can it stay “a way” forever?

GC: No, but that’s what’s so condescending about it. Everybody knows it can’t stay “a way” forever. But the paternalism, in that case, was off the charts. Everybody knows things don’t stay the same, especially if you live in New York. But the idea that somebody would say to an elderly woman who loves her neighborhood, who’s been on the front lines, who goes to all these meetings, and talk down to them like that—what I learned about the EDC is that they are just horrible at community relations.

They learned a little. You could tell they were learning more over time. Over a few years, they tried to make a noticeable effort to change their methods. They stopped talking about esplanades, and stuff like that. There was a change. But it took a long time.

NL: Yeah, three years.

GC: And it took us beating a few projects. We kind of beat them into it. Now they’re gone; we’re rezoned. But they started to focus more on affordable housing, at least talking about it. They started to focus a little bit more on claiming to listen, which was more of a deflection tactic. Instead of trying to force us to agree with them, which was their original approach, it became more, “We’re hearing you; we’re going to make the changes.” Changes would never come. It became a much more defensive project, and that’s when you realize that they were never there for the community. Their function is to stop community resistance, that’s what they’re there for. And we all knew that. A reporter submitted a FOIL request for their emails and that’s exactly what they confirmed, basically—that they never even considered our perspectives.

We were able to put together an alternate Community Plan—at the City’s request, saying that this is something we should be doing! The idea was, we’re not going to just say no, no, no to the rezoning. I knew development was going to happen, and most people did, but we didn’t want our whole business district decimated.

What the reporter found in the emails was that EDC communicated one-to-one with developers. Developers emailed, “I want this change,” and EDC responded. The reporter, a young guy, goes to me, sincerely, “Did you have this kind of back-and-forth with the EDC?” And I was like, “No, of course not!” All they would say is, “Just hang on, later in the process is when we make the changes.” So, you see that this was for the owners, and a big waste of people’s time.

April De Simone: I think what stands out is what did change with EDC. I think what you were saying captures the humanization process that we’re talking about. Individuals are put in these positions of authority and come in and change community experiences, but if they are unable to humanize the community, then it becomes much easier to detach themselves from the results of their work. And this has been the case throughout history—this is not a different tactic, this is not something that just started now, it’s been like this since the inception of planning and land speculation.

Moving forward with the coalition—because it’s happening anyway, the cost of living is increasing dramatically—what do you think are going to be outputs or tactics that are going to manifest in the built environment that are going to build upon equitable and inclusive experiences?

GC: Well, first let me just address what you said about humanization and dehumanization. One of the weird things about the EDC is how detached they are personally. They’re also very thick-skinned. They come in and get yelled at by the community, and essentially have no reaction.

NL: We would yell in their faces, and they would just—nothing.

GC: With the real estate industry in general, there’s a distance that’s created. We never see the property owners and they don’t see us, and that makes it easier. That’s how I know that they know somehow, on some level, that they’re committing bad acts. Their distance from it is a tell.

But with the second part of your question, I think we altered the conversation a little bit, especially around affordability. We and other organizers around the city have driven home what affordability is and isn’t. The Mayor’s HUD-based concept of affordability, AMI, is just not realistic. That’s something that we hammered home. We made a case for deep affordability and for using public land as a place to do really deep affordability.

“We and other organizers around the city have driven home what affordability is and isn’t.”

We won contextual zoning, which is a weird thing because contextual zoning in many cases is an exclusionary tactic to keep out low-income people. But we said, “A tool is a tool; it depends on whose hands it’s in.” In this case, we saw it as a tool to limit developers’ incentive to snatch up properties and develop soft sites into luxury houses. Our goal was to try to do our best to mitigate the market pressures somewhat. I don’t know how successful we were in doing that, but time will tell. Where they are going to build in Inwood is going to be mostly on industrial sites. As EDC had determined, there would be little direct displacement. And I shouldn’t say little—I think it’s like 200, and that’s a lot.

AD: And they always underestimate the displacement.

GC: And what they don’t estimate, and there’s a lawsuit over it, is indirect displacement. They calculate anybody who’s in a rent-regulated apartment as secure, which is—I could laugh. It’s ridiculous. As tenant organizers, we spend all our time protecting rent-regulated apartments because of all the different mechanisms that exist to get them out of their apartment. My building just got hit with two Major Capital Investments (MCI’s), and they are illegally deregulating apartments. So, to say that people in rent-regulated apartments are secure is not true.

Our goal was always to limit the number of people that would be uprooted. Because nobody was caring about the people already here; everything was about who’s coming in. Our goal is to give people a foothold and to lessen the pressure on them. We were demanding more tenant organizing money; we didn’t get all that much. There were a lot of other demands that we wanted along with this, plus a lot of us are already engaged in the rent reform battle. But I would say, just put very simply, our goal is to keep people in their apartments and not create such an alien environment.

That’s one of the reasons, too, that we pushed for contextual zoning. They were looking at, like they’ve done in other parts of the city, building these giant glass buildings. And you look at a neighborhood like Inwood, and people are sitting outside, they’re connecting, people know each other. Then you drop this doorman building down with residents who will say, “Oh, these guys blasting merengue or playing dominos are scaring me.” Then the building’s doorman will call the cops, and now you have the cops coming over. It disrupts the street life, it disrupts the community, it disrupts the culture. That’s another thing we were extremely concerned about. And we still are.

Our goal is to keep people in their apartments and to limit the number of luxury units. I think there are tangible human and cultural issues when you have such massive amounts of wealth coming into this neighborhood.

NL: Do you see any similarities between the ways that your tenants’ association has been engaging with your landlord, for example, and the way that we engage with the City in general on the rezoning fight?

GC: Well, there’s no communication with the de Blasio administration! In three years, he never came to Inwood once. But when we communicate with our landlord, again, there’s no direct communication. The landlords don’t talk to us. I mean, we’re suing; we have a class action suit against them. We did have a pretty big win—we got a bunch of apartments reregulated. So, you do get your victories here and there.

There’s so little communication. But I think that this is where the mass pressure from organizing works. Even if they don’t directly speak to us, you can see their rhetoric change. I think Francisco Moya was a good example, where for the first time, the Chair of the City Council subcommittee on Zoning and Franchises put out a scathing letter about the problems with rezonings. That was in response to the Inwood rezoning. For the first time, you weren’t just hearing, “Oh, these are great ways to create affordable housing.” It was a demand that people start to see the problems in the zoning.

NL: But it took a lot to get there because we had individual meetings with as many council members from the Zoning Committee and from Land Use that will give us the time of day. We shared our platform; we shared the research. We had tenants go and share their stories of how much they’re at risk, even though EDC is claiming that they’re not at risk. We clocked in a lot of hours at City Hall and inviting them to the community to come around and talk to the people.

Co-op City. Image credit: formulanone via Flickr.

AD: I don’t know if you read recently that the National Housing Coalition is touting Co-op City as one of the exemplary model developments for the limited equity co-op, that you could buy for $20,000 and live there. Here’s the situation of what you were speaking about with the disconnectedness: for so long people have been saying, “We did Amalgamated, we did Co-op City, why haven’t we recreated those similar models?” All this development that has come in, not one has simulated what they did. And it’s this disconnect.

You’re telling white progressive liberals that there are models out there, why aren’t you advocating for these? And when you say it, the response is, “Oh, that’s impossible, it was a different time.” And then all of a sudden now, everybody’s starting to talk about the limited-equity co-op. Those very same people that said, “No, no, no, we can’t do that.”

You’re on the front lines with this activism. How do you call this out in these circles?

GC: I know a lot of people in real estate. Some of them are the nicest people to talk to, absolutely lovely people if you get to know them. But they are just so disconnected. They’re not evil; they just don’t know. Poverty is abstract, all of these problems are abstract. They know they exist, and then they think that there’s a fix. Many are very involved in these fixes where they think, “The system benefits me, it’s going to ultimately benefit everyone else.”

It’s a humanity problem. Because the thing is, if this real estate person, who I’m convinced is a decent person, was in the community and got to know people in the community, there would be a difference. I genuinely think that.

NL: Something that we’ve been also talking about is what we think people should do about this. There’s always a distance between folks who are in power, the people who are powerful and wealthy, and those of us who are not and who feel the impact of not only their amassed wealth but also the decisions that they get to make every day about the issues. They decide what the fixes are, and they go in between the system that has allowed them to prosper right at the expense of others.

Do you think that there is this understanding that they are only where they are at because a lot of people don’t get access to the same resources and opportunities? Do you think that’s something that can be changed through a conversation? Or do you think that there’s more that needs to be done to break down those elements for them?

GC: The irony that I noticed in dealing with people who have power is that they all consider themselves very good, especially if they’re liberals and progressive, and they consider themselves on the right side of things. I mean, it’s a lot of paternalism, an idea that people just don’t get it. Their attitude is that we don’t get how the world is, but they do.

You’d have to have quite a conversation. It also depends on the person. Some of them are self-made people. They have their attitude of, “Well, I made it, other people can make it too.” The old pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps idea. Although they have more of a grounding in the realities, they just think that everybody has to shape up. When it comes down to the ones who grow up with wealth, they still believe it could be all fixed through a gentler form of—

NL: —of change. They don’t think that they must give up anything to do it.

Alp Bozkurt: What does housing justice mean to you?

GC: It’s a simple thing. We want to remove the fear that people have in their lives; remove the suffering and what it does to children, what it does to neighborhoods, what it does to friends, what it does to families. We’ve got to stop displacement. And on the local level, how are we going to stop it? As far as the bigger picture, I don’t see how a system where owners are far, far removed… I think of it like The Matrix, where they have people in those pods and they’re sucking their energy out. That’s what I feel renters are like. We’re in our pods and they’re just sucking money out. And it’s like, how many more ways to get the money out are there? “Let’s turn it up, turn it up, get more money out of it!” It’s such a commodity—how do we squeeze every dollar out of this?

If you’re in a situation where housing is this kind of relationship, it’s so dysfunctional. It’s dehumanizing. It’s been going on for millennia. I don’t necessarily know how to fix it.

I’m a believer in finding ways for people to be owners. I mean you can see the difference in how they treat owners. In Inwood, one area that was not touched—in fact, it received a historic district—was where all the co-ops are. We have friends there, people who help us out. But it’s always been like that in history. You know, the landowners could vote. Having that kind of stake gives you more power over your own life. I’d like to see more people having ownership, as opposed to just being at the mercy of property owners.

Note from the Fellows: In December 2019, in a lower Supreme Court judge’s decision the 2018 Inwood rezoning plan was annulled, however the City is currently appealing the decision.

Graham Ciraulo (he/him/his) is a resident of Inwood, Manhattan and a volunteer community organizer for housing justice. He is an active member of Met Council on Housing, serving on the organization’s Board of Directors, and was one of the co-founders of Northern Manhattan is Not for Sale/Alto Manhattan No Se Vende, a neighborhood coalition that fights predatory rezonings. Graham is also active with Altagracia Faith and Justice Works, serving on its Board of Directors, and the Good Shepherd Church Justice, Peace, and Integrity of Creation Ministry (JPIC), where he facilitates the Tenant Rights Working Group. He is a leader in his tenant association, the Lower Seaman Tenant Association, and co-President of Uptown Community Democrats.

Header image credit: The Northern Manhattan Is Not For Sale Coalition