The Urban Design Forum’s 2018 Forefront Fellowship, Shelter for All, addressed the homelessness crisis in New York City by examining how to dignify the shelter system through better design and exploring the root causes of homelessness and housing precarity. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on how to address the prison-to-shelter pipeline, public bathrooms, public realm management, supportive housing, and racist housing policies, which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

The following interview with Chris Burbank, Vice President of Law Enforcement Strategy for Center for Policing Equity, accompanies Homelessness in the Public Realm. Read the full set of Shelter for All proposals and interviews here.

Madison Loew: Can you tell us about your experiences addressing homelessness during your time as police chief in Salt Lake City?

Chris Burbank: Salt Lake City has always had a fairly significant population of individuals suffering from homelessness. As in most cities, when the area started to gentrify, we started to see more conflict. Early in my career, the homeless shelter was built in no man’s land. It was near the railroad tracks and some very seedy bars. Nobody paid any attention. But then as the city started to grow and the need for urban housing amplified, we started to see tremendous conflict.

What we tried to do at the police department was to address the underlying cause. Right away, we identified our 20 most frequent flyers. These were people that actually spent the most time with officers in the police department. And they were all homeless. Most of them had drug, alcohol, or mental health issues, or a combination thereof, and had extensive arrest histories. Some of them, over 500 arrests—and that’s not an exaggeration—in their lifetime. 500 arrests. If we arrest somebody 510 times, are we going to change the outcome?

So, we started to look at, what is the underlying cause of what’s going on? Those individuals were costing the city and police service alone about $1 million a year. We developed a very forward-thinking initiative for housing first. We gave all these individuals transitional homes. Some of their housing was contingent upon them attending counseling or taking medication, but it was never, “Alright, you have to stop drinking, or you can’t have this house.”

We adopted a model in which police officers would not just arrest people for quality of life issues: trespassing, urinating in public, intoxication in public, and some of those other things that just are vicious cycles that never solve anyone’s underlying issues. We started to say, “Well, okay, here’s how you go about getting a job.” In fact, at one point, there were several of my officers, on their own time, who were driving eight individuals to a job that the captain of the division had arranged for them in a garden shop.

Not only did we stop making some arrests, but I also told my officers, “You can’t write jaywalking tickets anymore.” Because what we found was that we were only writing them to homeless people. We were only writing them around the shelter. And as far as race, they were very biased in who they were being written to. I just said, “No, we’re not going to write those anymore. Anywhere in the city.” And the fact was that we weren’t writing them anywhere else in the city.

That developed an avenue to have dialogue with people, as opposed to just, “I’m going to get you off the street, and out of sight, out of mind.” We, in society, feel threatened, endangered, uncomfortable in the presence of some individuals, and the police have been the tool to move them along. We started to see that we could actually change the circumstance, as opposed to just shuffling people through the criminal justice system, which obviously was not having a good outcome.

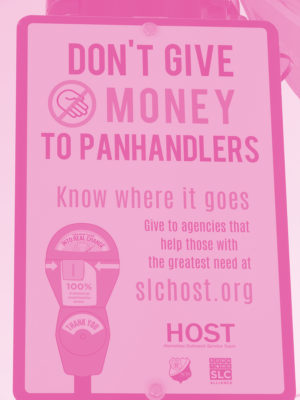

Sign in Salt Lake City.

ML: Could you tie some of those experiences to the work that you’re doing now at the Center for Policing Equity?

CB: At the Center for Policing Equity, we focus on the intersection between the public and the police, and more specifically, between race and policing. We try to determine what are the underlying causes of the disparate outcomes of the criminal justice system.

We ask, “What is the underlying cause of this? And what is the contribution of policing to that outcome?” Because when you talk to law enforcement, they always say, “Well, we just go where the crime is.” By that notion, you would then say, because of the outcomes of the system, that Black people in America commit more crime than people of other races, which is not true. There have been countless studies that have demonstrated that race is not an indicator of criminal activity or criminal behavior.

When you start to talk about homelessness and these other things, they’re very similar. The homeless man on this street corner asking for money is not a lot different than the Black man walking down an alley in any given city. And now you make that homeless person a Black male, 25 years old, who’s large in stature, boy—the perceived threat he poses to society is significantly higher. There are fascinating studies that talk about our perception of Black men, or men of color, being older, stronger, bigger, larger, more intimidating, and that plays into policing. We need to recognize, this, to say, “Yeah, that’s driving not only who’s calling us but how we deal with people when we show up.”

What are we going to do to change it? And then, most importantly, how are we going to measure that to make sure that whatever we are doing is actually working and changing the outcome? We do a very poor job of measuring when it comes to law enforcement. We train officers, we make rules, laws, but we don’t actually look and say, does it change behavior?

ML: And when it comes to changing behavior, I know that was a big part of the training materials that you work on at the Center for Policing Equity. Could you talk about those training materials and the scale at which you have brought them to so many different places?

CB: The idea is to have people recognize that within themselves and also within the systems in which they work—and hence, quite frankly, the society in which we live—bias is interjected constantly. And it exists in a lot of different forms. It is gender bias, it is race bias, it is bias against individuals suffering from poverty. We all have these preconceived notions that we have in life.

It’s very hard to recognize and understand the biases that we have towards most issues of race, and homelessness, and poverty, which are deeply ingrained in us. If you have had a life experience that has made you believe a certain thing about race, about gender, about someone poor, it is very hard for me to change that core belief that you have within. But what I can change is how that’s projected in your behavior.

Let’s start to look at what we can measure very easily: it is behavior. Measuring your feelings are more difficult. Talk about your feelings, measure behavior. Combine the two, and then you can change the outcome.

That’s what the training is there for, to recognize what we have within ourselves, to recognize what’s being imposed because of someone else, or society, or the system in which I work. And then, to recognize the things that I can do to change the outcome.

Some of those can be very difficult situations, especially when you talk about a homeless individual, whether it’s private security or police. Private security usually represents a property owner of some type. And someone is on their property or on the fringe of their property, and they are often asking for money. They are viewed as a disturbance or a hindrance to someone coming in, to what they would view as their customers. The call is either to private security or to the police. We often fall into that mode of, ”How can I deal with you right now?” And that is often, “Do you have a warrant? Are you doing something inappropriate? Or can I send you on your way? Do I have enough authority to say you can’t be here, be down the street?”

One, that just creates someone else’s problem. And two, when we do just take somebody to jail, it doesn’t break this cycle of them coming back or going somewhere else in society. Now it may not be my problem anymore, but it’s someone else’s problem.

We start to learn and understand and educate people: What is the end? Why is this person homeless? What are their needs? Is it a job? And then, what are the factors that go into getting a job? It becomes really easy to say, “Oh, yeah, go get a job.” But when you show up with only the clothes on your back to get a job, sometimes it’s very difficult. What do you do with your backpack, your shopping cart, your box, or whatever it is, that you are carrying your possessions around in every single day, that most cities in their homeless shelters don’t provide long-term storage for? Now I have to bring that with me and go. Well, if I’m bringing all that to somebody and saying, “Hey, here I am, give me a job,” that’s very difficult. If you have small mental health issues that are controlled with medication or a little bit of therapy, and you don’t have access to that, how are you going to get the job if that manifests itself in the middle of your job or job interview?

What is that underlying cause? You can change people long term. It is not the mass change, it is not the fast change, but it becomes the more permanent change.

ML: That gets us to our next question, which is, what does a more compassionate public realm management specifically look like? I would love to hear about metrics, because you brought up metrics a couple of times. If you’re held to certain metrics, then you’re going to be held to certain outcomes.

CB: I believe public spaces should be available to the public. I may be radical in that, in particular circumstances. And when I say the public, that’s everybody, to share and to participate in.

Sometimes that is hard because of how we design public spaces. Over time, there’s been lots of, “Well, you don’t put seating down because if you put seating down, then the homeless people are going to sit.” Well, if you don’t put seating down, then I’m not going to sit there. I don’t want to be facetious by any means, but they want me to sit there. They want the responsible middle-aged white guy to sit there and participate, because that is the notion that we have in society of safe, good communities. I mean, it’s not right, but that’s exactly what it is. The idea should be that is it accessible to everyone to participate.

The way you do away with disorder that is inappropriate, you’ve seen it done most successfully with programming. When spaces are alive and vibrant and participating, then you don’t have those negative things. And this is where you really have to draw the line. Looking, acting, behaving differently than someone else is not disorder. I am talking about theft, I am talking about assault; not looking, not asking for money.

If there are avenues to have a discussion if somebody is not meeting the expectation of the space—avenues to have discussions about why not or how can they, are much more important. I’m not talking about just allowing anything to take place. But when those individuals are causing that disturbance, the question is not, “Get out of here, go to jail tonight.” The question is, “How can I help you tonight? How can I change your circumstance so that you can be here and not be the problem?” And we can do that.

The majority of people, when you ask the question, “What can I do for you tonight? What is it that you need?”—you start to differentiate, and then you actually start to solve the problem. We have tremendous resources available to us in this country that are not available to everybody.

ML: Can you say more about the resources?

CB: When I think about health systems, job placement, clothing, and meals that are available in Salt Lake—because I’m obviously more familiar with that—there’s quite a bit of opportunity. Nowhere near enough; I’m not saying we’re oversaturated. But very rarely are those people that are encountered by law enforcement or private security given the means to obtain those services, because the criminal justice system prevents that.

People don’t understand. I mean, I know nothing about your circumstances in life, but I’m willing to bet that if you get a speeding ticket tomorrow, it’s going to be expensive and it’s going to hurt and you’re going to be upset that you got it. But you pay that speeding ticket and go on with life.

If you are deciding whether or not to pay the ticket, or get food, or drive the car, there is tremendous disparity. It does not equal justice, based on your socio-economic status. And then that becomes overwhelming. That speeding ticket, when it becomes a bench warrant, becomes an arrest warrant, becomes an arrest on your record that when you go for housing now you tell people you’ve been arrested before. That’s a significant challenge in this day and age of computers, because people check on that.

ML: This brings us back to the metrics. What are the behaviors that you feel are incentives given the current metrics set up for law enforcement today, like writing tickets or arrests?

CB: We as the public are responsible for that. It is our expectation of policing that we arrest, that we write tickets, that we are proactive in the work that we do. We don’t like it and we hold the police accountable when crime goes up. We oftentimes say, inappropriately, that when crime goes down it’s because we did such great police work and we did extra enforcement. But when you really look historically at some of the things that we use to measure success, the arrests don’t correlate to decreased crime, the number of police officers doesn’t correlate to safety.

For example, a few years ago when the economy turned downward, in one year over the next 40,000 fewer police officers were working than the year before. Crime, and especially violent crime, declined dramatically during that time. In the mid-90s, we arrested more people and incarcerated more people than we ever have in the history of the world, and violent crime was at an all-time high. Now we think that if we arrest more people and crime goes down, we take credit for it. We’re measuring the wrong metrics.

“…when you really look historically at some of the things that we use to measure success, the arrests don’t correlate to decreased crime, the number of police officers doesn’t correlate to safety.”

The other thing that I find is a very faulty metric—when a police agency puts up arrests, how many of those are repeat offenders? How many of those are multiple arrests of the same individual in the same year that you’re counting? Did you solve the problem by having to arrest them twice? And were you twice as good because you arrested the guy twice?

Let’s say the metric is much better if you show how many people you don’t have to arrest. How many people didn’t go to jail? How many people received diversion out of the system and didn’t have to participate in it? And then consequently, how many of those people didn’t come back?

ML: Throughout this conversation, you have made several great comments addressing the last question I had, which is, what will it take for public spaces to be truly for all?

CB: We often point fingers inappropriately at law enforcement and at security. “It’s their fault, they’re less sympathetic.” What we need to change is our expectation as a society and our expectation of safety and wellbeing. Until we change what public expectation is, we are still going to have a machine that shows up and takes people away in order to make other people feel safe.

Again, there are people who need to be out of society. But it’s a small, small percentage. When we look at the majority of people that we incarcerate in this country, they are there for misdemeanor things. That’s not right. When you start to look in any city, at the number of people who are incarcerated daily for quality of life things that we can change, what we all in society need to say is, “Let’s change what the expectation is of policing.” Then our spaces will truly be public and accessible to all people. Because we don’t have that need to divide society.

Chief Burbank serves as Vice President of Law Enforcement Strategy for Center for Policing Equity. He has been involved with CPE since its inception, utilizing their research capability at the height of the immigration debate, and supporting their efforts throughout the Nation. He is an unwavering advocate of the National Initiative and Justice Database as solutions to waning public trust and confidence in policing. Chief Burbank was with the Salt Lake City Police Department from 1991 until his retirement in June of 2015. He was appointed to the position of Chief of Police in March 2006, becoming the 45th Chief of the Department. During his nine-year tenure as Chief he distinguished himself as progressive and innovative, influencing not only the City of Salt Lake but also the profession.

Header image credit: m01229 via Flickr