Editor’s Note: In 2010, the National Park Service announced a plan to refresh and refurbish perhaps the most visible civic space of our democracy, the National Mall, visited by over 25 million people every year. In 2011, the Trust for the National Mall announced a design competition to rethink three of the sites on the Mall: Union Square, with an oversized reflecting pool barring the flow from the Mall to the Capitol Building; the Sylvan Theater on the Washington Monument Grounds, which had been bifurcated by a recent security upgrade; and Constitution Gardens, which had never been fully realized since its inception in the 1970s. The winning proposals will shape the designs of Constitution Gardens and the Sylvan Theater, though issues of jurisdiction will alter the final renovation of Union Square.

Christopher Beardsley, Executive Director of the Forum, sat down with three of the finalists to discuss visions for renewing these sites on the Mall: Kathryn Gustafson, representing the Gustafson Guthrie Nichol and Davis Brody Bond’s team for Union Square; Rob Rogers, representing the Rogers Marvel Architects and Peter Walker Partners team for Constitution Gardens; and Marion Weiss, representing the WEISS/MANFREDI and OLIN team for the Washington Monument Grounds at the Sylvan Theater. We’ve also included some comments from Skip Graffam of OLIN, who was unable to join the conversation but who sheds new light on the proposed landscape surrounding the Washington Monument. –DM

Washington DC National Mall

Chris Beardsley — Redesigning a landscape as present in the public eye as the National Mall is ambitious. What were the most meaningful challenges you set out to resolve as you reworked your individual sites?

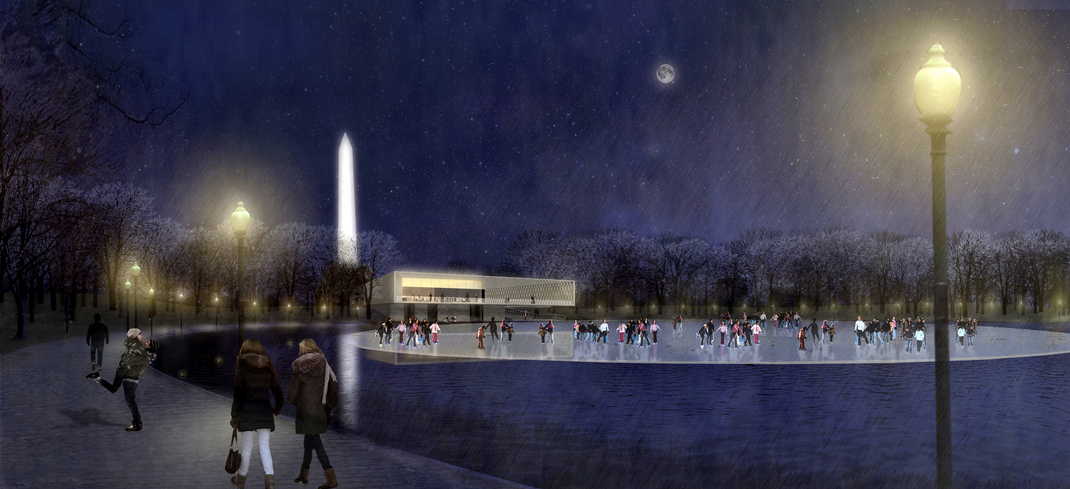

Winning design for Sylvan Theatre

Courtesy of OLIN and WEISS/MANFREDI

Rob Rogers — The present physical condition of Constitution Gardens is pretty rough. The work by SOM and Dan Kiley in the 1970s was really an idea structure for a generation of modernity addressing the mall. Unfortunately, it wasn’t executed very well. The soil is disastrous and the topography is actually very mild. We thought that a modern landscape and modern building actually do belong on the Mall. We felt like the conceptual underpinnings of the Kiley-SOM effort were solid, but needed to be re-invented, certainly reconstructed, and the building very much reimagined.

Peter Walker and Partners have proposed a soil and garden reconstruction that will develop a landscape that emphasizes the unusual nature of this place with higher topography and a healthy wooded landscape. It also has a lifespan that’s appropriate to the mall. There are 40-year old trees there that are half the size a 40-year old tree should be and that has to do with the at-grade conditions.

In that context, we proposed a building in Constitution Gardens. Not a building to compete with other buildings on the Mall, not a monument, not a museum, not a memorial. It’s a parks building. It had to be just enough building to contain the program elements that parks need. The most ambitious and most formal aspect of the building’s program is an overlook into the park itself.

You’ll know that you’re entering a secluded and special area that is distinct from the French axial-garden formality of the rest of the Mall. Constitution Gardens is very specifically a respite; it is not full of historical material because it’s only from the 1970s. It’s neither a memorial nor a monument; this is a playful moment on the Mall. Of course, you’re in the context of memorials and monuments. So the building is a shell; it’s not a mass. It’s very light in spirit. It’s horizontal, not vertical. The intent was to let this be a restful, delightful park in the Mall, which is a highly formal place otherwise.

Marion Weiss — Alice Pike Barney, the founding donor behind the Sylvan Theater, said that performance and culture belong on the Mall, not just symbolism. She chose the word “sylvan” because it was evocative of the theaters that Shakespeare had described with the magic of the forest. There was no sylvan in the particular proscenium that was created. We felt we could address a couple of things and go beyond.

The Sylvan Theater is located dead center between the Tidal Basin with the cherry trees–which are so famous and fabulous–and the formality of the monumental Mall. As such, our project had an opportunity not only to offer a new outdoor theater and a pavilion for food and visitor orientation services, but also connect these two disconnected landscapes.

By re-orienting the theater, we are able to create a naturally beautiful sylvan amphitheater through the artifice of elevation. We propose raising the elevation of the amphitheater so that the audience can simultaneously watch the stage but also have a one-of-a-kind view, at the same time, of the Mall and the Washington Monument. The addition of elevation to the amphitheater accomplishes something else: it conceals the tourist bus drop-off area while enhancing the view to the Tidal Basin. Right now, if you’re standing at the Washington Monument and you’re looking in that direction, all you see are buses. Now what you’ll see is a green slope with the Tidal Basin beyond.

Furthermore, by introducing trees, we were able to capture the spirit of a sylvan landscape by having a grove of trees rise and descend and offer dappled light into this amphitheater. Moreover, we have added elevation that allows us to cross existing roadways and connect to the Tidal Basin. As a result, we’ll finally link the waterfront and the Mall.

The pavilion, together with this amphitheater, maintain a sinuous line that keeps a low horizon and a green roof that make it as much a part of this landscape as it is a piece of architecture. Together they welcome people coming out of tour buses or from the Mall to grab a drink or a bite to eat.

Flexibility for a whole range of performances is also at stake. Small performances can take place at one end of the stage, medium performances for up to 1,000 are set within the main amphitheater, and large performances for 10,000 and beyond can leverage the landscape of the site and the Washington Monument’s slope. Within this pavilion, also dappled with light to simulate a tree canopy, there is an interior amphitheater where small performances can operate in all seasons.

National Mall competition photo

Skip Graffam — One of the central challenges was to insert a variety of new visitor programs in a way that respected and enhanced the iconic landscape of the Washington Monument and cross axis of the National Mall. We knew that this needed to be a solution that read primarily as a landform and not a collection of buildings. The form of the Sylvan Theater flows from the base of the monument, staying below the monument’s entrance plaza level to reinforce the existing composition of the site, key viewsheds, et cetera.

The key is that the landscape is flexible and multifunctional. The Sylvan Theater will be a state-of-the-art performance venue in the spirit of Alice Pike Barney’s original vision as well as a destination and attraction when there is not a performance.

Kathryn Gustafson — Union Square has two major roles: first, it is the face of the nation and the view of the Capitol. Second, it becomes part of the city for the inhabitants and visitors to enjoy. How do all of these things work together? What happens during large public events like the inauguration? It is really as a place that’s very secure for the Capitol and the inauguration, and yet still open for other uses. It was a complicated piece to design.

One goal was to keep the monumental reflecting pool honoring the Capitol and giving monumental termination to the mall. That pool would be very flexible, but at some point, it has to be this monumental gesture that bookends the Lincoln Memorial and the Capitol. We thought it was very important to represent the federal government while recreating this space. The reflecting pool has five flexible segments. Some segments of the new reflecting pool can be in water while others can be in paving. The new design uses a whole lot less water than the current reflecting pool. The proposed system does not throw that water away but holds it and recycles it. The new site will be essentially water-neutral.

Rob Rogers — Everyone who saw that scheme was taken aback by its graceful capacity to handle both individuals and massive crowds.

Christopher Beardsley — It seems that all of these projects try to straddle the line between activating the existing landscape by adding programs but also leaving it open to embrace spontaneous activities. How did you find the right balance between programming and flexibility?

Marion Weiss — That is the opportunity and challenge of doing something in such a public area. The needs will change when there’s a crush of tourists at one moment or at a quieter moment, say, in the winter season. Anticipating adaptability and change in the landscape means considering the emphasis of use and also what it will be like when it’s not being used.

We wanted to have a wonderful amphitheater pavilion during performances and otherwise. Flexibility allows our stage to grow and shrink, so a small event and a large event will both feel at home. Its proximity to the Mall means it could be a dining terrace for special events. Landscape is wonderful that way – in its ability to be elastic.

Rob Rogers — The Constitution Gardens building is a pavilion by its very nature. It’s a building you go through, not just in. It’s meant to be functional for a small party or for hundreds of users. If you’re asking specifically about flexibility of the landscape, Peter Walker was very intent that the Constitution Gardens be a garden. That distinguishes it from landscapes on the mall. He focused both on how it performs through the seasons and the way it accepts a casual picnicker, a large group of strolling walkers, or ice-skating in the winter. It has vibrancy as well as flexibility.

Kathryn Gustafson — Union Square is very different than Sylvan Theater and Constitution Gardens because it’s at the end of the mall. It’s part of the monumental, formal, and civic definition of this space. It has a ceremonial role. The role of each of these places is extremely different from the others: the Sylvan Theater is performance-based, whereas Constitution Gardens is leisure-based. Union Square has a double role. First, being a ceremonial representation of the federal government because it is the reflecting pool of the Congress. At the same time, there’s an important need to make our cities more livable for the everyday residents. So Union Square has to provide spaces of gathering and leisure.

Rob Rogers — Union Square is under the most stress: to go from a few people strolling and having an idyllic view of the Mall to withstanding the inauguration. Constitution Gardens is a specific site. Although it may swell with seasons and crowds, it doesn’t have the same radical variation and intensity.

Kathryn Gustafson — Constitution Gardens is almost a destination. You have to joyously discover it! It’s this jewel tucked in there.

Union Square is at the end of the axis. There’s a lot of pressure on it. It goes from Constitution Avenue to Independence Avenue on either side. It encompasses some very interesting ecological projects: the Botanical Gardens and what we call Site 575, where we’ve proposed a new outdoor museum that explores the natural world and native ecologies. We, as a culture, are looking at the sustainability of our lifestyle, so fittingly this very intense monumental space will be bracketed by these two concerns.

National Mall competition photo

Christopher Beardsley – That’s a good point. Obviously the National Mall symbolizes the values of our government and ourselves as Americans. What values were you trying to inscribe in the Mall through the projects? Obviously sustainability is a piece of all of them.

Skip Graffam — One of the most wonderful things about the National Mall is that it’s our country’s collective stage for celebration, protest, exhibition, recreation, and engagement with our government and collective culture. There is no better place than a theater to continue that sharing and exhibition of culture, through a flexible venue that welcomes all groups to participate.

The close connection between our country and the native landscape was celebrated with the reconnection and re-stitching of the fragmented woodland into a sylvan grove that forms the theater and connection of the monument grounds and tidal basin.

Marion Weiss — Issues of sustainability are in the foreground of everyone’s thinking today. On one level, we’ve all proposed physical changes that ensure that these buildings and landscapes are sustainable. We have reduced lawns, so that meadow and lawn better complement each other to reduce maintenance. We have rain gardens to collect rainwater runoff so we can reuse it for irrigation. We have the benefits of a green roof, daylight harvesting elements, and so on.

The larger question of sustainability is, with 25 million visitors now and in anticipation of that number doubling in the future, how can this be a compelling destination? How will it thrive? To some extent, it means connecting parts of these landscapes that were disconnected. It means making sure that a cafe can support itself so that it is not a burden. We are connecting performance-goers with their community, so that people come to the Mall not just as tourists but as “homeowners” of this “backyard.”

Kathryn Gustafson — You’re right: we can create spaces that improve inter-urban living within Washington DC. You’ll take your kids and your grandparents there. You’ll walk there. It’ll be part of your daily life, not just for an occasional fair and then empty again. The Mall will become a more integrated part of the city so that people don’t feel the need to leave the city to find that breath of fresh air, exercise, or whatever it is they’re looking for.

Rob Rogers — The wonderful thing about having all three sites part of this competition is that they are distinct types of public space. For us, it was this idea that the Mall is available to anyone who lives and works in the area. For the tourists, it’s actually quite a long haul to make your way from memorial to monument. The memorials are incredibly moving and emotionally exhausting. To have places where you just take a break under a shade tree, by the water, or in a restaurant while in the middle of the Capitol is a way to think about how this can work for many generations.

Kathryn Gustafson — These projects also serve as precedent for designing functional and beautiful integrated landscapes in our cities. As the Capitol, there’s an obligation that our projects use state-of-the-art technology, materials and planting ecology.

Christopher Beardsley — Being the National Mall, there are obvious security concerns. How did you balance security concerns with maintaining open, connected landscapes?

Rob Rogers — At Constitution Gardens, we ended up referring to long-learned rules of personal safety about when people feel comfortable. Our site doesn’t have larger security obligations. We’ve not yet been through the process with the agencies to discuss whether the pavilion will require any special requirements, but we’re going to try not to at this point.

Kathryn Gustafson — Union Square is driven by security in many ways. Having worked in DC for quite a few years, there are a couple of key points we had to keep in mind: first, the tried-and-true rules of what make people feel comfortable, and the need for an additional layer of security features. The design adds a second security wall at Third Street, the western perimeter of Union Square, and security measures are integrated into the landscape to make them less visible. Security was one of our main drivers from the very beginning to ensure we could meet the requirements that might be asked of us in the future.

Marion Weiss — Security is very important around the Washington Monument. In advance of our design for the Sylvan Theater, OLIN developed a low wall that works around the Monument as an oval, which responds to the core security concerns at the site.

Skip Graffam — The balance is achieved when the security elements are rendered invisible or become an amenity, as is the case in the Washington Monument security wall, which serves as a new plinth for the Monument, seating area, and vehicle barrier.

National Mall competition photo

Christopher Beardsley — This is really the first time that the Mall has been rethought in several decades…

Rob Rogers — Really since the 1970s project by Dan Kiley and SOM that was the genesis of both Union Square and Constitution Gardens. It’s interesting that those two sites are both now up for reconsideration. Peter Walker noted that that the landscapes of Constitution Gardens only lasted for thirty or forty years, which is unfortunate. His firm, PWPLA, has really developed the science, technology and craft that can rebuild Constitution Gardens to last for 100+ years.

Chris Beardsley — What is the anticipated lifespan of your projects? And how often should the Mall, as a symbol of our nation, be redesigned and reborn?

Kathryn Gustafson — We have to be careful, the Mall has suffered constant shrinking. It’s interesting that the Trust for the National Mall has decided to rework existing sites instead of creating new ones.

We’re reducing our public domain footprint and we’re reducing our permeable surface footprint.

I’m all for rethinking the Mall but not for adding more. There are a couple of places you could add a building, but we are going to just eat this up. It’s happening to parks all over the world, where buildings are starting to encroach. We’re reducing our public domain footprint and we’re reducing our permeable surface footprint.

Rob Rogers — In the early 1800s, the population of the entire United States was half of the current visitorship of the Mall. How could you ever have designed for, or even imagined, that kind of usership? Kathryn’s right about the preservation of what is there. We can create places that actually invite and enable congregation. But we don’t know what it’s going to be like 20 or 50 years from now.

Marion Weiss — The evolution of this landscape goes way back. The Tidal Basin originally engulfed much of the Mall today, effectively crossing almost to the Washington Monument. The site of the Lincoln Memorial used to be water. Constitution Avenue was a canal. This has been a very vibrant set of transformations from a site of exchange and trade to a site of symbolism. There have been many views of it, from the grove of trees filling the Mall by Andrew Jackson Downing in the 1850s, to the open clarity that emerged with the 1902 McMillan Commission vision.

Whether the Mall’s form takes on a symbolic identity or a bucolic identity has evolved through fashion, you might even say. What we’re looking at right now is a landscape that embraces visitors and yet still preserves the legacy of a generous open landscape. Kathryn may be right; to some extent, the Mall can no longer support new structures. The magic of the “between” spaces has become so compressed and roadways have divided the Mall from other landscapes.

Collectively, we’ve been looking at how we can construct sites that are leftover bits into elements that can be enjoyed by the public and connect visitors to other landscapes. And that’s where our bridging landscape is hoping to afford continuity between the Mall and its larger context. It’s all part of this new evolution of thinking toward landscape.

For more information from the design competition, visit the Trust for the National Mall.

Christopher Beardsley is Executive Director of the Forum for Urban Design and Editor-in-Chief of the Urban Design Review. Kathryn Gustafson is Principal of Gustafson Guthrie Nichol, a Seattle-based landscape architecture firm. Rob Rogers is Principal of Rogers Marvel Architects, a New York-based architecture and urban design firm. He has been a Fellow of the Forum since 2009. Marion Weiss is Principal of Weiss/Manfredi, a New York-based architecture and urban design firm, and the Graham Chair Professor of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania School of Design. She has been a Fellow of the Forum since 2006. Skip Graffam is Partner of OLIN, a Philadelphia and Los Angeles-based landscape architecture firm.

Image Credits: (1) Union Square proposal, Gustafson Guthrie Nichol and Davis Brody Bond. The Trust for the National Mall. (2) Constitution Gardens proposal, Rogers Marvel Architects and Peter Walker Partners. The Trust for the National Mall. (3) The Washington Monument Grounds at the Sylvan Theater proposal, Weiss / Manfredi. (4) Union Square proposal, Gustafson Guthrie Nichol and Davis Brody Bond. The Trust for the National Mall. (5) Constitution Gardens proposal, Rogers Marvel Architects and Peter Walker Partners. The Trust for the National Mall. (6) The Washington Monument Grounds at the Sylvan Theater proposal, Weiss / Manfredi.