The Urban Design Forum’s 2019 Forefront Fellowship, Turning the Heat, addressed ways urban practitioners can advance climate justice principles across New York City. In partnership with the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, Fellows surveyed neighborhoods, studied buildings, interviewed local and international stakeholders, and produced creative research on mitigating heat. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on creating circular economic and sustainable models in NYC, developing community resiliency within NYCHA housing, factoring design into preventative care, and establishing a climate first approach to housing which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

The following interview with Will Thomas, Member of Open New York, accompanies Just Climate, Just Housing. Read the full set of Turning the Heat proposals and interviews here.

Renée Crowley: Can you tell us a little bit about Open New York and what their mission is?

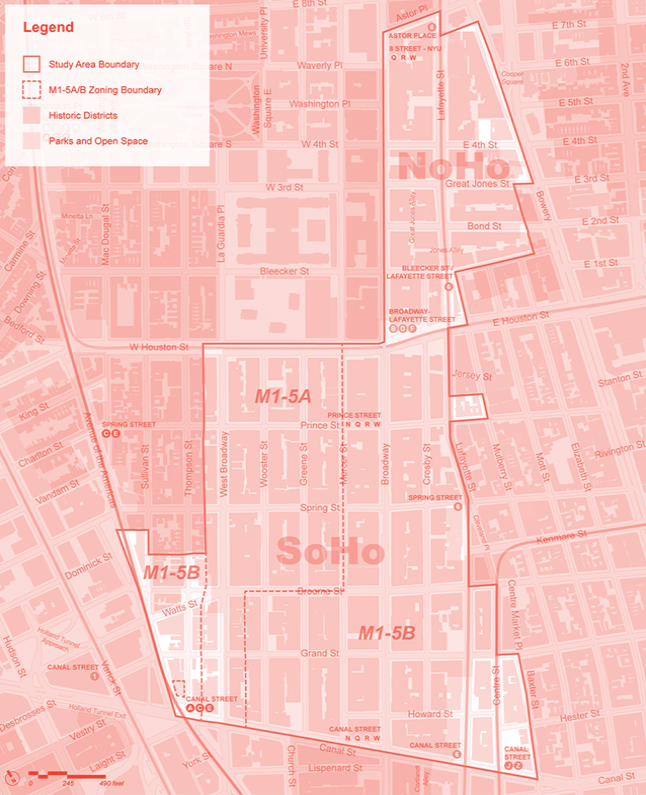

Will Thomas: Open New York focuses on allowing more housing in high opportunity neighborhoods. We see that being as important for equity reasons, for affordability reasons, for environmental reasons. Usually, we advocate for two swords. We’ll show up for individual ULURPs in Bronx or Brooklyn or Manhattan or western Queens. Generally, we try to focus our advocacy on higher opportunity neighborhoods, so wealthy neighborhoods, transit rich neighborhoods, neighborhoods with good schools. We also advocate for neighborhood rezonings as well. When we started, we were focusing mainly on those individual projects. We’ve also advocated for the Gowanus rezoning as well as the Soho/Noho rezoning. Unfortunately, those are the only two neighborhood rezonings that have been proposed for wealthy neighborhoods, but we’re hoping that will change obviously.

RC: Could you talk about Open New York’s position on the Soho/Noho upzoning?

WT: The city essentially started this process with the aim of just legalizing retail. We went to the original rezoning hearings and they weren’t pushing housing. I think it’s clear in other places like Southern Boulevard, or Bushwick, that the city representatives came strictly to advocate for housing. In Soho at the meetings, it was pretty evident that what they wanted to legalize retail, which is kind of odd that retail isn’t legal in Soho. We thought it was ridiculous that the city was planning on rezoning two of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the country without that housing focus, without any plans for increased density or affordable housing.

The mayor has been pushing those rezonings in Bushwick and in Southern Boulevard where the council members are obviously opposed. By contrast, Margaret Chin hasn’t taken a position on Soho at all, so it was this big opportunity that we were leaving on the table. We attended these meetings and it was clear we weren’t going to see the progress that we wanted to see within the process that they had set up. In July, we decided to go outside the process a little bit and release our own plan.

We essentially proposed two separate rezonings—one is outside the historic district and the other is inside. Outside the historic district, we planned to rezone more generously to allow sort of the same densities that are allowed in Yorkville on the Upper East Side. Within the historic district, we realized there was a lot we could still work with given that the existing buildings in Soho are actually quite dense. We proposed allowing new construction on non-conforming sites to the density of the densest building on the block. We found that those two proposals together, both the more generous rezoning outside the historic district and the more limited rezoning within the historic district, would deliver 3,400 units of housing and almost 700 units of deeply affordable housing.

RC: How do we prioritize housing for the population of workers in the Soho/Noho area? What kind of mechanism could be put in place to meet their needs?

WT: We started from the point of wanting to expand the community preference proposal because we’ve heard a lot of criticism about it. When it’s in these very wealthy neighborhoods, you’re preserving a lot of affordable housing strictly for people who were already in those neighborhoods. A lot of times, that means that NYU students, because their income levels are technically low, get preference in affordable housing compared to people who are working in retail shops in Soho. The proposal was to open it up to all of Margaret Chin’s district so that people in the Lower East Side and in Chinatown would definitively be able to get preference for it.

It is ridiculous that people who work in these neighborhoods don’t get preference for the affordable housing in it.

It is tricky in that people do change jobs. However, a big motivating factor was that building more affordable housing in high opportunity neighborhoods might mean that a job change might be a change for the better. When your commute is much shorter, and you’re much closer to Midtown and the financial district, maybe you can get a higher paying job somewhere else.

RC: Why is it important to upzone a neighborhood? What’s the big takeaway message from doing this?

WT: I think there are three major opportunities that we get from upzoning Soho. The key benefit is integration—Soho is 72% white and the median income is well over $100K. We have demographic analyses that show that upzoning would increase the low-income people living at Soho by 40%. In terms of education, in Soho and Noho have the best school district in the city, according to the Furman Center. When you’re opening up the neighborhood, you’re giving 700 families the chance to enroll in that excellent school. There are also environmental benefits—you have 3,400 households in an incredibly transit rich neighborhood. This is a region of Manhattan where the subways are under capacity. It’s a very natural place to allow growth. You won’t have as many people driving from Staten Island, so it’s a huge improvement on in terms of emissions.

Soho/Noho are also very important in terms of symbols. We see it is as very important to change the politics of development. The administration has only upsold low-income and gentrifying neighborhoods. They do this because they see wealthy neighborhoods as being politically impossible to upzone.

Asking for an industrial neighborhood to take all the city’s growth has understandably generated a lot of resentment, but it’s not getting us the housing.

Showing that this can happen in both rich and poorer neighborhoods would be very meaningful.

RC: What would you say is a high opportunity neighborhood? How do you clarify that and what your criteria?

WT: We have understood it to be a loose metric of whether the median income is above that of the average for New York City. We haven’t defined it super strictly. I think everyone would agree that Soho and Noho are high opportunity neighborhoods, in addition to the other neighborhoods that we’ve advocated for like Kips Bay and Boerum Hill. They all have very high income and amazing schools. As we turn our advocacy to more of the city, I think we’ll define what high opportunity means more strictly.

RC: Does your team have any neighborhoods that you’ve considered working with that could be the next?

WT: We have discussed the Village and Tribeca, which is right next to Soho. I think all of brownstone Brooklyn as well. There are other neighborhoods that aren’t as well served by transit, like Bayside. There are a lot of neighborhoods that can be doing a lot better, from Greenwich Village to Bay Ridge. Both of these neighborhoods aren’t building anywhere close to the amount of housing that Bushwick is even without a rezoning.

RC: What are the major opposition points that folks in the community bring up about the Soho/Noho plan, or in general on upzoning in wealthy neighborhoods?

WT: In Soho, the major two points of opposition are local homeowners and organized in groups like the Soho Alliance and the Bowery Alliance of Neighbors. There are also preservationists like the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Their major motivation is preserving the character of the neighborhood and local property values play into that.

We went to a community board hearing and recorded the co-chair of Community Board 2 saying, “With all the historic character of the neighborhood, I don’t think Soho should be as responsible in terms of building more affordable housing as other neighborhoods.” I think that captured a lot— the important thing is protecting the history rather than expanding opportunity. Even beyond that, people don’t want the subways to get more crowded and people don’t want the schools to be more crowded. It’s a classic opportunity hoarding playbook.

RC: If we’re going to be able to upzone the neighborhood, build new buildings, or renovate existing buildings to be compliant with the city’s goal to reduce energy and carbon production by 2050, what does that look like?

WT: There are a lot of us within Open New York that strongly support sustainable building. In order to get that sustainable building, we need to first allow building. Newer buildings are much more energy efficient and environmentally friendly than even retrofitting an older building would be. Enabling density is a first step—it’s important alongside strengthening those regulations and it might help also to expand some regulations of older buildings. We want to look at per capita emissions metrics. If we were to double New York’s population, we probably blow past our current emissions in total. But our national emissions would likely plummet because New Yorkers have 30% of the carbon emissions of the average American. Having the right measuring stick is very important here.

Right now, the current development that is happening nationally is that the Sunbelt is exploding in places like Phoenix and Tampa. They are rapidly sprawling and creating these terrible infrastructure messes that we’ll be living with for 30 years. Even without reform to New York’s building regulations, allowing for high rise development would decrease carbon emissions and could redirect the sprawl in this city. There are improvements that we could make in terms of our regulations, but it’s always important to have in mind what’s currently happening

RC: Has Open New York referred to any other cities or neighborhoods that have been adopting pretty progressive policies or practices?

WT: The big one is Minneapolis and how they got rid of single-family zoning—that’s a big example of how we might use comprehensive planning. LA has a robust transit-oriented development program. In California more broadly, in terms of statewide initiatives, they have EDU laws that have pried open exclusionary suburbs. Also, Massachusetts has a really interesting anti-snob zoning law, which I think is how most development happens in a lot of cities, unfortunately—that is a more of an equitable solution. The Mount Laurel court system in New Jersey opened up a lot of exclusionary subgroups as well. I think these examples show that these issues need to be addressed on a statewide plan, as opposed to on the individual council district level.

Will Thomas is one of seven board members at Open New York, an all-volunteer, independent, pro-housing nonprofit. A marketing professional by day, Will has worked as a volunteer housing advocate for over two years, fighting for rezonings in high-opportunity neighborhoods across the city, such as Kips Bay, Boerum Hill and Nolita.

Header image credit: Medium article by Open New York