The Urban Design Forum’s 2019 Forefront Fellowship, Turning the Heat, addressed ways urban practitioners can advance climate justice principles across New York City. In partnership with the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, Fellows surveyed neighborhoods, studied buildings, interviewed local and international stakeholders, and produced creative research on mitigating heat. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on creating circular economic and sustainable models in NYC, developing community resiliency within NYCHA housing, factoring design into preventative care, and establishing a climate first approach to housing which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

The following interview with Jennifer McDonnell, Resource Recovery Program Manager for the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, accompanies Circular Systems. Read the full set of Turning the Heat proposals and interviews here.

Rebecca Macklis: Could give a quick introduction to yourself and speak to how you entered the sustainability and circular systems world?

Jennifer McDonnell: I have been in the field of what I call resource recovery for about 15 years. I had a bit of a circuitous route to my current role, which is as the resource recovery program manager for the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). My job here is to develop programs to recover the resources within the scope of our operations, which are water and wastewater treatment for NYC. I primarily focus on biosolids here at DEP.

As the backstory of how I got to DEP, I recently came from a company that was in the biosolids management industry serving 85 customers on the East Coast making all different kinds of biosolids and residuals that we worked to recover. Prior to that, I was the, so-called, Green Mission Specialist, for Whole Foods Market in the Northeast region – loose translation is that I was the environmental coordinator. There, I worked on recycling and composting programs at the retail stores. I started in retail, got interested in food resource recovery, ended up in a food waste recovery company that actually was a biosolids management company first and foremost, and then became really interested in biosolids, and then came to DEP.

RM: For those who aren’t familiar with biosolids resource recovery, would you be able to give your elevator pitch of what that is?

JM: Sure. Biosolids are the solid byproduct of wastewater treatment, in the sense that they result from the processes within a treatment facility.

Advanced wastewater treatment, which is what’s in place in New York City, is a multi-step process that involves physics, chemistry, and biology, with the ultimate goal of cleaning water and returning it to the waterways. As part of that process solids are separated. Those solids can be recovered as a resource – for energy, nutrients, and more.

RM: Great. Thinking of how the world of biosolids is plugged into circular systems thinking, can you provide background on how you interpret circular systems thinking, and how your experience, both at DEP and your previous experience at Whole Foods, has helped you inform how you approach the topic of biosolids as part of this larger puzzle? In short, do you view biosolids as one sphere of circular systems thinking, or part of a larger whole?

JM: At the heart of my personal passion on this resource recovery or circular systems thinking is efficiency, and in the acknowledgement that the resources around us have value, that everything has value in some context. The challenge is finding that value, realizing that value, and trying to use it in the most efficient way. Efficiency for me means both financial and logistical. I’m a fan of the McDonough Braungart Design Chemistry thinking which focuses on biological and technical nutrients, and trying to keep things in their cycles.

The concept of “resource optimization” is the fundamental way I approach the topic of circularity, both in the work that I did before and here at DEP. It’s astonishing how much energy and effort we put into moving things around rather than thinking of ways to use what we have. Perhaps a simplified way of putting that circular thinking into context; when you think about everything in the modern conveniences of life, how much stuff that you consume is actually produced near you? How much is recovered near you? Very little. Biosolids are an example of this. In NYC, they are produced locally and shipped “away.”

RM: Expanding upon that and looking to opportunities for further efficiency, could you provide an example of an approach or principle that you utilize in your current role? And perhaps speak on an approach that you are utilizing in your current role that you wish you had in your past private sector roles, and vice versa?

JM: One thing that is very important to the planning that we’re doing now is using the same concepts familiar in our world but applying them in different ways. For sustainable biosolids management we realize that we’re going to need diversity. We’re going to need a lot of different uses and different products. So diversity but not in the way maybe most commonly thought of, as in of people.

The city makes a lot of biosolids, every day, and we need to be creatively thinking about all the different ways that we can use it rather than an all eggs in one basket approach. That’s something that I’m using now and that I wasn’t as aware of in past roles.

In my private sector work I was involved in a number of successful partnerships. This is much more difficult in the government sector. There’s movement, I’d say in governments – not just New York City – to tap into “public private partnerships”, particularly as we go into this more circular economy and try to engage with functions that are outside the core functions of government. I think government in general is kind of siloed, and that does not lend to a circle.

I think it’s fair to say that the private sector is a little more nimble in partnering and figuring out business relationships, and that’s not the same structure that government utilities work in.

RM: Would you say that that ability to be nimble and partner cross-sector and cost discipline is one of the biggest roadblocks standing in the way of expanding this type of practice? Or is that just one piece of the puzzle?

JM: I think it’s really just one puzzle piece. A larger one is the way that the economic drivers exist in our society, and that’s translated into demand for products.

Aside from biosolids, yet a similar story, is other commodity recycling. For example, glass. There’s not a high demand for recovered glass, it’s cheaper, often, to make new glass. And cumbersome and challenging to recover used glass for reuse and recycling. For biosolids, an example would be trying to tap into its value as fertilizer. It may not necessarily be cheaper to get “virgin” or fossil based fertilizers, but the whole distribution system is set up around them. The governing rules are set up around their use, and the farmers are comfortable using them so it becomes a herculean effort of shifting entire circles within the economy.

RM: You speak about these larger networks and relationships of supply and demand. Taking a broader look at these topics perhaps outside of the lens of biosolids and resource recovery, can you speak to an approach that you would suggest for regular folks across the city that would like to engage in these topics and help move the needle? Or perhaps to others working in the city but not directly engaging in these systems?

JM: It definitely requires cross sector collaboration and leaders within those sectors that are willing and able to collaborate.

A design thinking exercise would be to look at our assets in place and how we can transform them. How can we use what we already have? That’s a very circular thinking approach to solving problems and that’s what DEP can do with the wastewater facilities – how can we optimize them? Can we put food waste into the digesters and get more gas? Yes we can, let’s do that.

RM: You mentioned political movement and incentive. Could you speak more about the political movements required for this in addition to the social movements. Can you speak to how communications ties into this thinking, both how the government and City agencies are communicating our thinking about these topics, and how the general public is being communicated to about these topics?

JM: Different types of communication are going to resonate with different groups. In order to be effective, you’re going to have to have a multitude of communication styles and mediums that can reach different audiences to resonate with them, whatever that means for that group. That’s really challenging, especially in a very diverse urban environment, and New York City is exactly that.

In the work I did with food waste recovery, prior to coming to DEP, it was such a challenge to communicate to people what was compostable; it kind of blew my mind. It was one of the most frustrating things for me – I didn’t understand why people didn’t understand.

I was trying to retrain folks who had been indoctrinated to throw stuff “away”. “Why can’t you put the bag of food in the trash?” Which is ironic because there is now technology that will separate the food from the packaging so that line has been blurred, but back when I was doing this education role for Whole Foods, that was bad and we couldn’t get it right. We tried communicating all different ways; different languages, images, in-person training, buddy systems. If we’re talking about communicating to get people to change behavior, you somehow have to find something that makes them want to do it, a motivating factor.

RM: Yeah, we have heard that line of “motivating factor” when speaking to others as well. To your point, some of the lines are blurred and it is complicated. I myself did a tour of the Sims Recycling Facility I think last spring, and it wasn’t until I did that tour that realized that compostable things aren’t actually recyclable.

JM: Yeah, it is complex and it’s very hard to communicate all these things. I think one of my personal challenges is that I want to be the best, I want to do the most, but my career has taught me that sometimes good enough is really good and better than not at all. Accepting less than perfect because perfect is not possible. I had a taxation professor who drove home the point that simplicity is at the expense of equity. It’s kind of the same thing with resource recovery, simplicity is at the expense of granularity – but in that space it’s better to get great participation on milk jugs and aluminum cans than try to have everyone know what to do with everything. That’s one approach.

RM: To your point, as a group our preliminary exploration of this topic seemed to show that a general social roadblock to this movement is that people get really jazzed about these ideas and want to do them, and then it seems so hard in the current environment to get to the perfect solution that the solution ends up being not necessarily mobilizing at all. Would you say that’s correct?

JM: Yeah, or they start arguing about what’s the best way, and get stuck on that and fail to move forward.

RM: On the flip side, for the skeptic conversation, which we talked a little bit about offline as well, what do you think is the most successful way, or what have you found successful approaches to try to sway skeptics that these systems are worth the investment and behavior change? Does this convincing require a communications game again, a political movement, financial movement, social movement, all of the above?

JM: I think it’s probably all the above. I was reading an article earlier today about the federal government telling states that if you don’t move people out of the floodplain we’re not going to give you money for resiliency. You think about whose responsibility it becomes to communicate with those people who must relocate. They are the ones who are going to lose, who are not happy with the result and you can’t blame them really.

When I think this through, conceptually I’m on board with the idea that we should not continue to invest in areas where it’s not worth it; we’ve lost the battle. Why would we do that?

But then I try to put on those people’s shoes and say well how would I feel if the Army Corps was coming to me and telling me that I had to leave? I don’t know how I would feel. I’m not sure that really answers your question but for me it is an example that reminds me that transitions, especially big ones, are not easy.

As far as communicating with skeptics, opposition to biosolids reuse has been an ongoing challenge ever since the Clean Water Act required biosolids to not be dumped in waterways. The answer is science and sharing facts. What has proven valuable in charged debates (and court cases) is having information validated by a trusted third party. Trust takes time and if you don’t have time, then it’s difficult. I didn’t start out a biosolids believer. Colleagues and mentors in the industry and years of following science and research made me one.

I imagine this would apply for private sector corporations who have things to “lose” as well – such as the fossil fuel industry. It’s probably easier for someone with a seat at their table to say, ‘hey, let’s get behind this’ rather than feeling like it’s coming from the outside. Maybe it’s too emotional for some people, emotional decision making is another aspect. That said, I think compassion goes a long way, and back to communicating, to understanding the different values that each party is trying to maintain.

That said, I think compassion goes a long way, and back to communicating, to understanding the different values that each party is trying to maintain.

Maybe the surface appearance of what’s important really isn’t the underlying thing. It’s taking the time to analyze that and get to the bottom of it.

RM: Definitely. And can you expand on some of the ways that DEP is doing that now, or how you’re doing that in your current role, as far as analyzing bottom line values, priorities, and co-benefits?

JM: Well for biosolids we are exploring the concept of partnering – within the limitations that exist. We’re engaging with the industry. We’ve hired someone to help us with that process as we go about it in an open and fair manner to have conversations with service providers to develop solutions.

For example, we need market capacity for biosolids recovery and it needs to be built. The industry needs to feel comfortable investing, or building something, with some security around a relationship with the City and other generators of biosolids.

Biosolids is a global space– everybody poops. Some of the macro trends are positive and exciting as the industry continues to mature. Emerging technologies such as pyrolysis or gasification, or extracting elements from the solids – like phosphorus. That’s one that the industry talks about a lot. Another thing we are doing is connecting with colleagues globally and sharing information and ideas for innovation in resource recovery.

The more traditional uses, e.g. compost or direct land application, are certainly things that are proven and beneficial and worth pursuing, but back to that diversity comment, the idea is to try to look at a number of different things as part of a robust program.

RM: Where is the type of innovation coming from?

JM: These technologies aren’t necessarily new, but based on what’s been happening with biosolids in the past decade or so as far as constrained landfill capacity and changing federal and state rules about some of the management techniques that used to be, “easier”, incineration being one of them, driving up management fees -there is a business opportunity. Technology that maybe 25-30 years ago was cost prohibitive. People wouldn’t invest R&D money in it, but that’s not really the case anymore. Rising prices are certainly a driver. Couple that with advancements in equipment and digitization of processes and monitoring – now some of these latent concepts are really taking off.

RM: That speaks to what we were saying earlier, the mix -of political, financial, and social incentives; that mixed basket rumble.

JM: When combined it’s quite effective to move the wheels forward. I would say the Regional Greenhouse Gas initiative is an interesting case study where the Northeast states banded together to try to limit emissions within their geography. I think there’ll be more models like this as people are trying to solve the climate problem. There really are a lot of people who are working on that.

RM: What do you think is the most exciting example, or best example of these applied circular principles that people are working on now?

JM: Our colleagues in the Netherlands at Waternet forged a public private partnership to make a face scrub out of calcite that was recovered from their water treatment residuals. Basically, a beauty product, and that’s a trending industry- that was super cool, and really my favorite right now.

Although my work is focused in the organics resource recovery space, the glass people have been working hard too because there is a lot of glass in the system that is not being reused. There are some creative uses being worked on there – such as a medium for growing microorganisms. Another one is the use of plastics to make roads. A few examples of folks in the non-biological commodity space. I try to follow many industries for inspiration on what’s possible.

RM: For these people that are innovating abroad or outside of New York City, what is preventing the direct application of this innovation within NYC? Can you speak to the overlaps and differences between where these things are happening and here in the city?

JM: What keeps coming up, not surprisingly, is the personalities and leadership that advanced some of these concepts. You have to have these champions and cheerleaders, you’re not going to get there without it. People have to be committed and have the energy to put into it and the motivation. Public policies are certainly another effective driver.

I don’t think there’s a shortage of those people, it’s just that they’re needed. I think that many of these shifts to circularity are not without headwinds, and you have to persevere and have the commitment to your goal. A lot of people that I run into, and internationally or otherwise in this line of work, they’re truly committed and passionate, that’s definitely a shared thing. The differences are sometimes cultural, sometimes political, and sometimes purely economical.

RM: So what do you think the next steps are for DEP as an agency, you personally, and the city as a whole? Where do we, we go from here?

JM: We’re going to have to enter into some new agreements, fundamentally different than those we’ve had before, to leverage the value of resources.

Personally, I want to crack the code on the economics, policy, and communication combo that works to shift the role of public utilities in NYC into circularity.

Personally, I want to crack the code on the economics, policy, and communication combo that works to shift the role of public utilities in NYC into circularity. I obviously can’t do this alone. I’m lucky to be part of a talented team – at DEP and in the City overall.

We also must continue to talk. The more people who start to understand these concepts and want to advance them, even if you can’t advance them in your own personal work. I think a lot of real change happens at the grassroots level.

RM: What advice would you give to those at a grassroots level currently struggling with a very linear economy that they’re trying to do something about either, in a different industry, different discipline, or in their own lives?

JM: I guess I would say, you’re not alone. Don’t feel alone.

I have to remind myself of is that incremental progress is progress. One of the hardest things for me and my career has been figuring out what that next step is, but the more you try to figure that out, the easier it gets. And you develop skill sets that help you figure out all kinds of different next steps. Is it meeting new people? Is it changing your point of view, is it going to a conference, is it focused thinking or finding someone else who’s done something that you can learn from? Is it talking it out with someone to help you figure out what that next step is? I think the next step is a tool that people may not realize. Figure out what that next step that is needed is and then you can move forward. Sometimes it takes a group to figure that out.

RM: There are these systems in plain sight that people who aren’t in the industry, but who are looking for something to take and learn from, often don’t realize that some of these systems are already in play in their everyday life. Could you speak to one or a couple of these systems that are hiding in plain sight that people perhaps don’t realize that they’re engaging with?

JM: Yeah, I think there’s an opportunity for us all to share more. We are all engaging with sharing opportunities. I carpool. I share my vegetables with my neighbors when we can’t use them. I share childcare with my fellow parents. I don’t know if it’s necessarily circular, but it starts to open your eyes to the interdependency of yourself on the world around you and being more open to those types of things. I think that can lead to more ideas and inspiration on what next steps might be. Interdependency is a foundation of circularity.

I’m also a big fan of really thinking about every resource that becomes yours to manage and owning the responsibility of finding it its highest and best use. I say that and my apartment is not full of crap! I really try not to consume very much. If I need something, I want to really need it, and go out of my way to get it (I do not Amazon) so that I appreciate it and am responsible for it until I’m done with it, and then try to figure out the best thing to do with it. And you can apply that thinking to your work also. And then that opens up possibilities around connecting things in a circular way.

RM: Something you had touched on in December was that historically our approach to these systems, across scales, has been to share and have accountability, which is really to have circularity. We have moved away from these patterns and now we’re kind of stepping back to them. Are we reinventing the wheel?

JM: Having the fortune to have visited parts of the world that aspire to be more, American if you will, and trying to understand really what that means, it became clear that this culture of consumption and convenience for whatever reason is seen as desirable. For example, meeting people who come to America and they’re so excited about being able to buy tons of disposable plates and cups and cutlery because they just don’t want to wash dishes anymore, and how easy that is and how there’s no “reason” really not to, especially if you can afford it.

One of the things I did when I was at Whole Foods was ask how we move away from disposables, because that’s not circular. The discussions about bringing real cutlery into the cafes were protracted and unsuccessful in the end.

It’s really this culture of entitlement. You want a salad. I’m going to give you a fork, too. For free.

There was an effort to try to either get rid of [the forks] all together or have reusable ones. It was too difficult to have reusable ones because of the cost and the loss and the washing and the labor and it just didn’t work out, and it wasn’t even seen as an option to not give someone the utensil.

I think there’s a simplicity in places that haven’t migrated to a disposable consumer culture, simplicity in the sense of less things. Life’s maybe not less complex, and that’s maybe a challenge in the way we define it as “more” work to wash your silverware, but I only have to buy it once and I don’t have to lug it home and take the trash out all the time. People are somehow comfortable with certain behaviors and not others. Maybe if we did some sort of mass balance or work study, is it really less effort in the end? Is it really easier to use disposable?

RM: I would say not. But it seems like there is work to be done to have the majority come around. Perhaps as a call to action, what do you think the future definition of these systems will be? What is the big takeaway next chapter for both the work of DEP and our city at large as we continue to think and work in this space?

JM: I guess this is supposed to be the high note end of our conversation, but I feel we have a long way to go. I think we’re going to be able to do more things with circularity here in NYC because we’re lucky enough to be in a place where setting up those types of systems would make sense. For example, back to the biosolids; we have so many nutrients centralized here already, because of our population. If it would make economic sense for anyone to become an urban nitrogen or phosphorus mine, it would be us.

If we start to think about those things, and pick a few to act on, I think we could be on to something. There was a professor at Rutgers, Kevin Lyons, he did this great study of mapping industry in Newark, and found out that there was a T-shirt manufacturer and a fabric supplier, but they weren’t connected so the T-shirt company was buying fabric direct from China. We don’t even know what’s going on around us.

There are simpler steps just connecting to advance some of these concepts. Unfortunately I think we’re really far way away from where we need to be and sometimes I get disillusioned because people talk so positively and grandly but it’s not real, and I prefer to talk maybe a little more softly about conceptual things and a little more loudly about things that are actually working and happening.

I’d be really interested if the reduced fare Metrocards got people out of their cars. I’d be really interested in hearing some stats on the plastic bag ban.

I’d be really interested to see if the City’s commitment to electric vehicles pans out and how many gallons of fuel we’ve saved by making that switch ..starting to really highlight things that are working, rather than talking at very high levels about somewhat abstract concepts like circularity.

I don’t know if that’s really inspirational, but I’m impressed with the number of people who are working in this space, and that’s why I always agree to participate in conversations because I don’t think there can be too much connection, and some of the things are going to turn into new things, and projects will happen and successes will be had and ideas will grow and flourish.

I also am a big believer in diversity in the sense of cross-pollinating what we’re doing. I was so glad you invited me to join your group because I guess I’m a non “traditional” type participant. That’s what needs to happen, conversations across types of participants.

Another Whole Foods example, we were focused on change around the end of the supply chain with resources that came into the store. I’ll pick on the fish people, we would say “Hey fish people, stop sending us fish in Styrofoam boxes”. Fish people said “well what do you want us to send it in?” We would say “something that is not Styrofoam and is recyclable”, and they said “okay but we don’t know anything else that will keep your fish cold and fresh without falling apart and costing lots of money.” So then we kind of looked at each other and realized, oh to really solve this problem we have to talk to the Styrofoam box maker, and we have to talk to the health code people about proper temperature holding time, etc,etc. So it becomes an exercise of bringing all the people together who have to solve a problem. On a positive note, the company did have a reusable tote program for a portion of the seafood supply chain that they had vertically integrated.

Another great story is how New York City joined with Chicago to shift from plastic to compostable cutlery in schools. With the two significant quantities of purchasing power they were able to get a manufacturer to commit to production. Sometimes you really have to do these things at scale. That is the way we tend to operate as a society. I think small scale stuff is totally awesome and it needs to happen. If you can, compost in your backyard – by far preferable to trucking it somewhere. But not everybody can do that. And we’re in a dense urban system so we’re a place where bigger things can happen.

RM: So it sounds like we have a long way to go but there are some tangible next steps that we could all take; sharing being paramount.

JM: And thinking about resources, taking ownership of your resources, and responsibility for them. Also having more transparency or general knowledge about what those resources truly are, and/or what their path to life has been; where they come from and what will actually happen to them after they leave you.

RM: Great. Well, thank you. Is there anything that you hoped I’d asked you we didn’t cover?

JM: I don’t think so, but I do want to give a shout out to design, because it solves many challenges when done well, and its potential shouldn’t be overlooked.

That’s what I’m excited about in the future; tapping into the creativity that’s out there, and using design to help people who have ideas about circular projects make them happen.

This interview was originally conducted in the first weeks of March, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Before publication, we caught up with Jennifer to see if she had anything to add in light of shifted context and amidst the pandemic. Here is what she had to say:

JM: The impacts of the 2020 pandemic on resource recovery efforts will be lasting. The most immediate impact is a constriction of municipal funding for projects as cost savings measures direct limited resources to core services. In my opinion, the need for innovative financing mechanisms and the ability for public resources to have their value realized is more important. This poses new challenges for bureaucracy, traditional utility service models, and the skill sets required in a more complex and interconnected working environment. Perfect conditions for innovation and industry disruption. It is going to be an exciting few years as we look to recover – and, as some have said, build it back better!

Jennifer McDonnell is a resource recovery professional with fifteen years in the fields of solid waste, recycling and biosolids management. Jennifer’s commitment to organics recovery was nurtured as the Green Mission Specialist for Whole Foods Market Northeast, where she led the adoption of commercial composting for over 40 stores. While at Casella Organics, Jennifer was part of the leadership team managing 800K tons/year of R&B throughout the Northeast. Currently the Resource Recovery Program Manager for the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, she is part of the Office of Energy, a group leading a renewed effort to increase the beneficial use of biosolids, realize GHG reductions, harness renewable energy sources and transform wastewater treatment to resource recovery. Jennifer has a dual BA from Brown University in Human Biology and Organizational Behavior, is a Certified Recycling Professional (Rutgers University), a Sustainable Resource Management Professional (SRMP) and a 2014 graduate of the Water Environment Federation’s Water Leadership Institute.

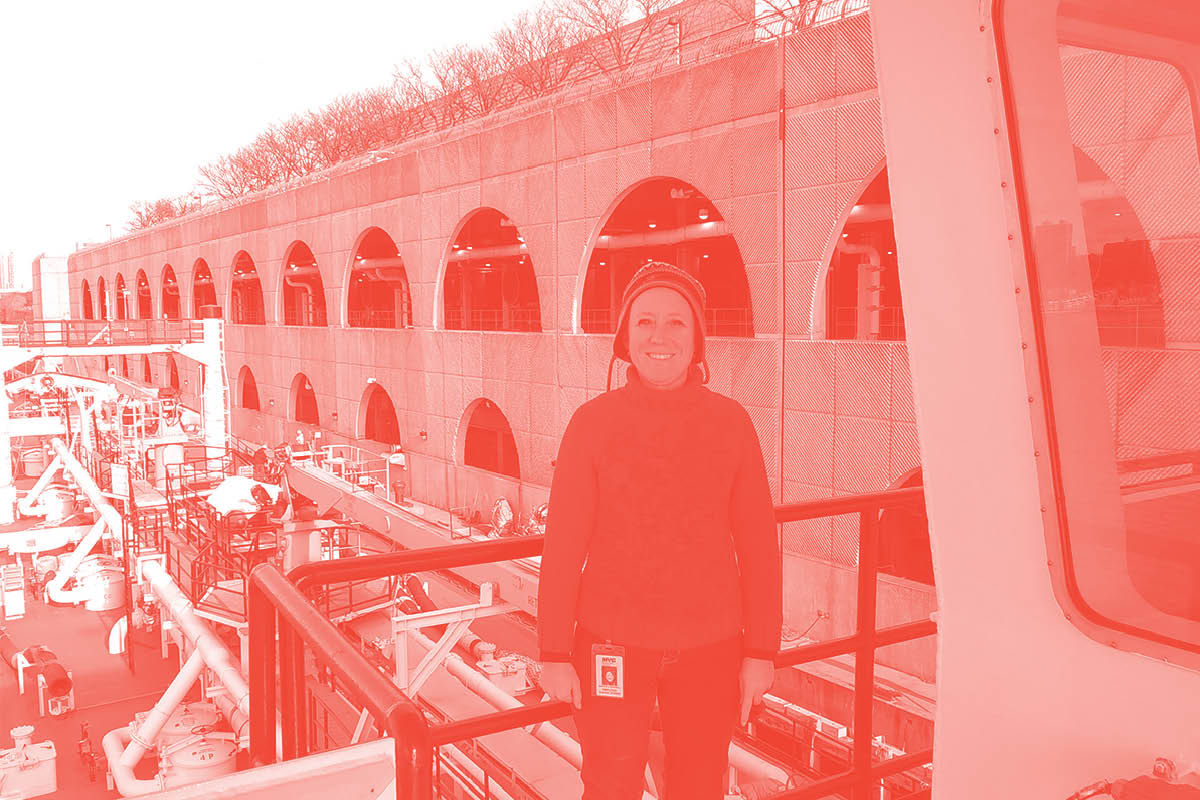

Header image: Jennifer McDonnell at NYC DEP’s biosolids trans-shipment vessel, docked at the North River Wastewater Resource Recovery Facility, West Harlem, NYC. Courtesy of Jennifer McDonnell

.