This fall, the Urban Design Forum is launching Cooperative Works, an initiative exploring how New York City can advance economic justice in its coronavirus recovery. In partnership with Deputy Mayor for Strategic Policy Initiatives J. Phillip Thompson and the Mayor’s Office of M/WBE, our Fellows will conduct research on how to create economic opportunity for MWBEs and employee-owned businesses through climate investment, leveraging the new market for building energy retrofits created by Local Law 97.

Leading up to the program, we are pleased to publish a series of interviews with leaders in sustainability in the built environment, inclusive economic development, and racial justice. In our interview with Daniel Aldana Cohen, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Director of the Socio-Spatial Climate Collaborative at the University of Pennsylvania, we discuss mapping neighborhood-level carbon footprints, building coalitions in the climate movement, and a Green New Deal for Public Housing.

Katherine Sacco: I wanted to start off by asking about one of your research projects, Whole Community Climate Mapping, which looks at household carbon footprint and climate vulnerability indexes at a neighborhood level. What have you found?

Daniel Aldana Cohen: The big idea of the Green New Deal is to create disproportionate investment in frontline communities to tackle climate problems and inequality at the same time. The Whole Community Climate Mapping project hopes to provide tools to make that easier by mapping how the built environment is associated with carbon emissions and localized vulnerability at the same time.

For example, it’s easy enough to identify the urban heat islands, and across the country, leafy (or cooler) neighborhoods are disproportionately whiter neighborhoods. But then we can also look at where people are having trouble paying electricity bills, such as for air conditioning. In Philly, there are neighborhoods with few trees but people can pay their electricity bills because those neighborhoods have gentrified. There are other places, very often communities of color that have suffered all kinds of discrimination, that have very high heat and a very high proportion of the income going to electricity. Those places are very vulnerable to climate change, as mediated through their economic situation. These areas where households cannot afford safe, cool, indoor temperatures should obviously take priority for doing retrofits, providing new and better air conditioning, and maybe modifying, increasing subsidies to, programs like LIHEAP, to help low-income households cover cooling costs.

We can think about tackling vulnerability to climate change and emissions at the same time by figuring out the neighborhoods where people are hurting the most. We can use data to respond to residents’ concerns, such as not able to keep the home at a safe temperature, then propose a solution that address both vulnerability and decarbonization all at once in the same place.

KS: We’re in New York, so I have to ask about the Carboniferous map that you put together a few years ago. What did you aim to achieve with this map? How can tools like maps contribute to the conversation around inequitable impacts of climate change?

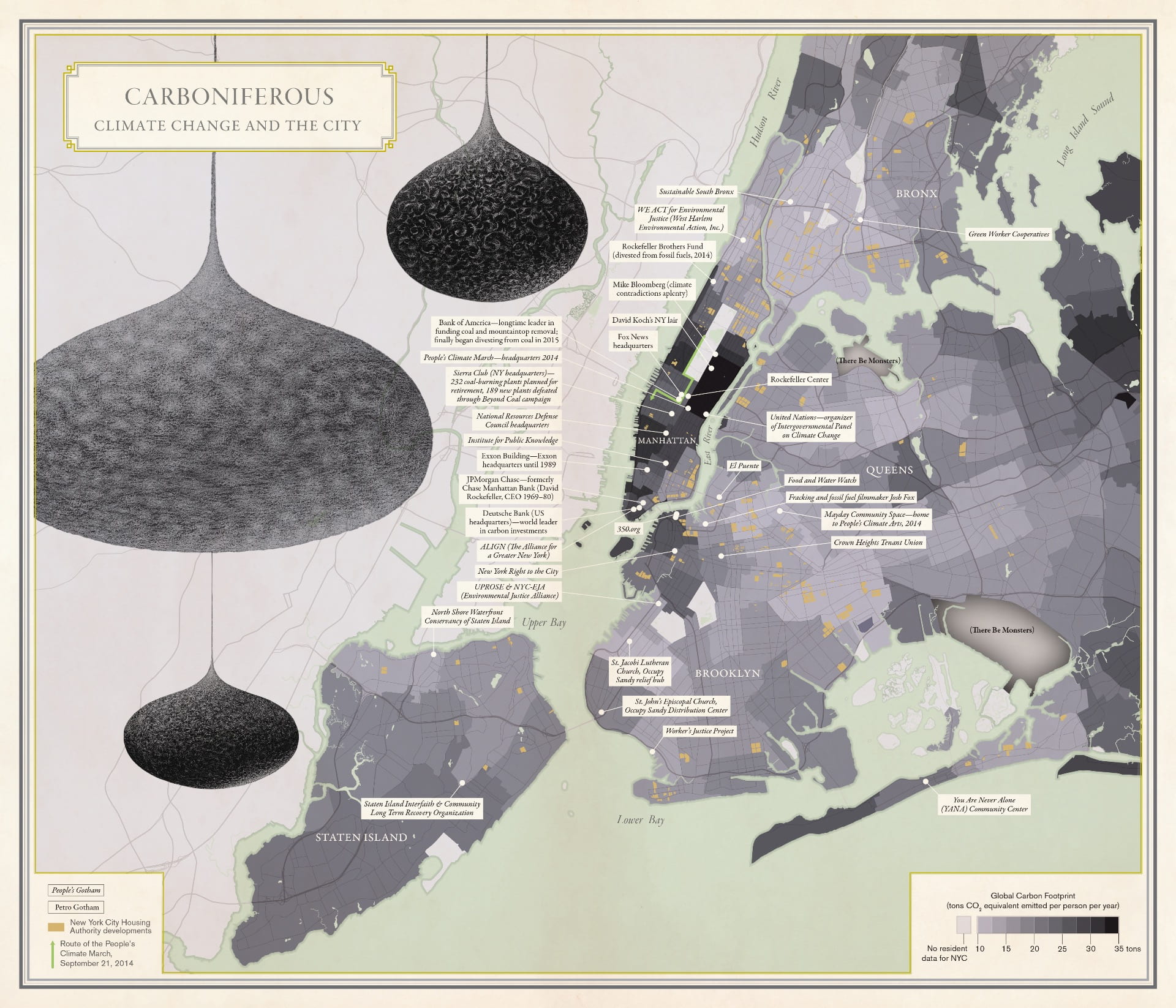

The Carboniferous map shows household carbon emission across New York City neighborhoods. Image credit: University of California Press.

DAC: The Carboniferous map shows the average household carbon emissions at the zip code level for New York City, as well as where the public housing is located. It’s based on data produced by my brilliant collaborator, Kevin Ummel, who is an environmental economist and data scientist. The map shows that there are two stories of climate and density in New York. The first story is of very affluent neighborhoods in Manhattan, and a bit in Brooklyn, with carbon footprints comparable to the richest suburbs, because the rich people there buy so much stuff, and fly so often. And the second story is of mostly multiracial, multi-class neighborhoods well-connected to transit, anchored with public housing with very low emissions. Some of that story is poverty, which is bad, but in middle-income communities, that’s where the density really shines as a low-carbon solution. This is actually what the future of sustainability looks like.

One key thing I wanted to express on this map is to debunk the idea that density is a carbon-free lunch—that you can have fabulous levels of affluence and consumption, and as long as you live densely then there’s no carbon problem. That’s simply not true.

KS: You helped to develop a Green New Deal for Public Housing. Why public housing? And why are you now expanding that lens to low-income housing in general?

DAC: Public housing is energy inefficient and poorly maintained, due to a massive repair backlog. The conditions are outrageous. A Green New Deal for Public Housing means that you tackle the buildings’ already existing problems and at the same time, you decarbonize them. It has a spectrum of benefits for residents, who probably don’t care about the carbon footprint of their electricity, but would certainly notice that they live in a much more comfortable apartment that has comfortable air conditioning in the summer, heating in the winter, no more mold, and cutting-edge appliances.

There’s another, subtler reason to start with public housing. Policymakers have more direct influence over a public amenity owned by the government. Instead of a subsidy or an incentive program for private firms, with the Green New Deal for Public Housing Act, we can say very specifically that three-quarters of the work done over ten years must be done by residents or low-income workers in that area, that the work must tackle all these other toxic issues in the apartments as well as decarbonisation, that there will be greater resident oversight than there had been in previous renovation projects.

Finally, through the scale of investment required for the Green New Deal for Public Housing, we’re going to create skills and capacities for small businesses and worker coops that can benefit the entire building sector.

We can apply those ideas to the low-income housing sector, except that instead of doing it through public housing agencies, we would do it through the Weatherization Assistance Program. A lot of us are talking about a massive scale up and expansion of the Weatherization Assistance Program to ensure that people of color and working class people can got new careers in the green building industry that will last their whole lives; to favor worker cooperatives and small-scale businesses; and to provide climate, health, and economic benefits to families.

KS: How do the tactics for climate policy change vary across the local and federal levels of government? What were some of the lessons you took away from the Climate Mobilization Act in New York?

DAC: One lesson from the Climate Mobilization Act is that you need strong mobilization from below, particularly in the housing movement. New York Communities for Change in particular played a key role. City Councilor Costa Constantinides, who introduced the bill, said on the floor of City Council: We have to pass this bill with provisions to protect un-rent-regulated apartments. We have to pass this bill so that when mothers and their children go to sleep at night, they’re not afraid of rising seas or rising rents. That is a really remarkable thing to hear, and something you never would have imagined hearing three or four years earlier, connecting climate change to housing insecurity in the context of decarbonization.

The biggest difference in terms of what you can do locally and federally is scale of funds. Cities and states can’t mobilize money like the federal government. The ingenuity of Local Law 97 is that the city doesn’t pay that much. What that law essentially does is compel businesses to finance their own decarbonization, which could save them money in the long run. Insofar as some Green New Deal provisions can be financed by companies and enforced through regulation, that is something the local sector can do.

What the city and the state cannot do is massive investments in NYCHA. But they have options. One is to use limited funds to give a bit to everyone. Another is to start at the level of transformation that you want to achieve ultimately with federal funding. New York State could certainly afford to do a Green New Deal for Public Housing-style deep energy retrofit for one or more NYCHA complexes, just not all of them. But if it did, and it’s kind of happening with NYSERDA, that would show the federal government what could be done. In a year or two, the federal government could expand on early experiments.

“One lesson from the Climate Mobilization Act is that you need strong mobilization from below.”

The same is true for low-income housing retrofits. We could try to do everything with on-bill financing so it doesn’t cost the state that much money, but then the problem is that no one is getting the kind of subsidy that might be necessary to move quickly and with deep retrofits. So instead of giving everybody a little bit, we’re going to deliver serious public investment to target strategic neighborhoods that are really hurting. Then we’re going to make the case for federal money to come and work on the rest of the city or state.

KS: In 2018, you wrote about the need to build climate coalitions that include grassroots as well as policymakers. How has the climate movement approached coalition-building in recent years? What are some of the biggest challenges that you’ve seen?

DAC: Housing groups, labor groups, racial justice groups, and policy elites come at the climate conversation in an asymmetrical way. The grassroots movements are underresourced, hammered every day, and fighting for survival. Often elite environmentalists are frustrated that grassroots groups that are basically dealing with climate change every single day don’t always foreground the environmental dimension and are somewhat suspicious of environmentalists. The resource asymmetry means that the policy elites will have to put in a lot of the front-end work in terms of figuring out what the intersections are between environmental issues and everyday economic issues faced by the grassroots groups, and then put together the spaces, both physical and metaphorical, for building trust. That’s going to take time.

I’ve worked with housing movements for years now, and it’s not like you have one meeting and then sign off. You have to provide support to those movements’ own struggles. The policy elites have to put in time to educate themselves and understand these links. Then they also have to put in time, and be patient, with coalition-building to build trust across that chasm.

Until you’ve done it, you don’t know what the forms of intersecting policy are going be. When we were working on the Green New Deal for Public Housing, it was really interesting to me to hear from NYCHA residents that they feel that they keep getting the worst appliances, because the procurement rules mean NYCHA has to buy the cheapest thing. I wouldn’t have paid as much attention to appliances if I hadn’t talked to residents about their everyday concerns, and that ended up being productive for creating a more sophisticated policy.

KS: How has the current pandemic impacted your work on climate policy? How do we approach the longer-term time horizon of climate change in the midst of a crisis that feels so urgent?

DAC: You have to see where we’re going, and then work your way back to the present and figure out the immediate next steps.

To me, the climate movement is not about, how do we just unplug from fossil fuel and plug into sun and wind? It’s actually about substantial reduction in overall energy use all across the built environment, from building materials, to energy use at home, etc. If you don’t do that holistically, you’re just transitioning from an oil-extraction economy to a renewable-energy mineral-extraction economy. That’s not acceptable and politically may not be feasible, because that would put so many new frontline communities into struggle.

With the built environment, we must identify the big systems we’re trying to rebuild, then translate that into short-term immediate political campaigns that have clear coalition partners with folks on the ground. Our wonk friends would do the carbon footprint analysis. Then we could go to groups and say, “We need to build a ton of new energy in New York State, and people are going to get mad. We need new consultation processes, and we need to find a way to expedite the construction of renewable energy in a way that communities upstate and downstate feel good about.” Then we go to housing groups and say, “If we’re blocking these natural gas pipelines, National Grid is going to hike the price of natural gas. We have to find a way to make sure that you’re first in line for swapping out those gas furnaces for electric heat pumps.” That way, we are building a broad, urban-rural coalition around a sophisticated set of demands, with long-term goals and short-term steps that build political power, and prevent unnecessary opposition.

The pandemic has to do with health, obviously, but when the health crisis becomes a little bit better, then it’s all about the economic crisis and the weather disasters. We need to find forms of decarbonization and resiliency-building that bring immediate economic benefit and safety to the communities that are hurting. That’s eminently doable.

Daniel Aldana Cohen is Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, where he directs the Socio-Spatial Climate Collaborative, or (SC)2. In 2018-19, he was a Member of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. He is the co-author of A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green Deal (Verso 2019). He works on the politics of climate change, investigating the intersections of climate change, housing, political economy, social movements, and inequalities of race and class in the United States and Brazil. He is also mobilizing collaborative research for Green New Deal policy development in partnership with progressive elected officials across the United States. He led the research for the Green New Deal for Public Housing Act introduced in Congress by Rep. Ocasio-Cortez. He collaborates regularly on Green New Deal research and public engagement with the McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology. And he serves on the policy team for People’s Action’s Homes Guarantee campaign.

Header image credit: Progressive Caucus of the New York City Council