As people moved to remote working during the pandemic, central business districts turned quiet. questions around how to safely and effectively reintegrate back into offices and bustling business districts have surfaced. Additionally, questions about who current work systems benefit were raised. These proposals investigate work from home gender inequality, internal design responses to make offices safer, and retrofitting existing buildings to accommodate social distancing.

Making New York in Long Island City

The Post-Pandemic City is a City for Women: Two Ways to Move Towards a More Equitable City for Caregivers

Using Behavioral Science as Design During COVID

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Urban Design Forum launched City Life After Coronavirus, a digital program convening Fellows and international experts to document global responses to the current crisis and to strategize a road to recovery for New York City. In April, we released a Call for Ideas to our network soliciting a broad range of submissions that envision how urban planning and design should change in the wake of Covid-19 as we strive to build a more just city for all New Yorkers. We are featuring some of the most compelling ideas in a series of reflections and proposals about diverse topics like education, community engagement, and mobility. Explore the full Gallery of Urban Ideas here.

CORRECTION: This gallery originally featured a response entitled “Remote Working and the Evolution of the City.” We have removed the piece pending review of its image rights.

Making New York in Long Island City

Long Island City (LIC) is a diverse, mixed-use neighborhood in western Queens and home to the longest continuously-operating industrial area in the country. Since the early 19th century, LIC has played a key role in the region’s economic development, producing everything from car parts to fortune cookies to award-winning movies. In the last decade, the neighborhood saw major growth in residential and commercial developments after zoning changes, while industrial uses remain and evolve. However, having industrial spaces close to the city center is not a given, and many US cities have lost industry in their core. Industrial businesses support the basic functions of the city and the region, employ workers at every level, and pay sustainable wages. More needs to be done to support urban industrial areas to retain and grow this vital sector so important for a modern city, especially in the post-COVID-19 world.

LIC’s Industrial Business Zone (IBZ) is home to a wide range of industrial users. IBZs are not zoning designations, but rather programmatic areas throughout New York City that receive direct business assistance and other resources meant to foster industrial growth and preserve manufacturing uses. In part due to these IBZ designations as well as its wealth of buildings suitable for large-scale production, LIC maintained industrial uses during its growth, setting up the neighborhood to respond quickly during a crisis and recover collectively after. COVID-19 makes apparent the importance of preserving industrial uses, but it is far from the only reason to do so.

In mid-March, as offices and retailers turned off their lights under the Governor’s stay-at-home order, New York’s essential businesses remained in operation to keep the city running and slow the outbreak. At 7 pm, New Yorkers cheered daily for essential workers and homemade signs in apartment windows thanked doctors, nurses, and grocery store workers. Another group of essential workers, though with less attention, also continued working: those in the manufacturing and industrial sectors.

Across the East River from Midtown Manhattan in LIC two manufacturers eagerly offered their help and joined many others to make and distribute essential supplies for the pandemic. By mid-April, Boyce Technologies, the advanced manufacturer of the MTA Help Point kiosks among other products, had pivoted quickly to produce a new, lower cost bridge-ventilator to free up more expensive ventilators for the most critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Founded in 2007, Boyce Technologies came to the LIC IBZ in the eastern part of the neighborhood in the last decade. Plaxall, a plastics manufacturer of custom packaging for toys, food, and cosmetics, began producing essential PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) face shields for healthcare workers. Plaxall has been in LIC for over 70 years, is a major property owner in the neighborhood, and is located close to the waterfront. These companies have different stories but a shared interest in innovation—and a shared neighborhood.

Manufacturing innovative equipment for fighting COVID-19 is just one small piece of the role Plaxall and Boyce play in LIC. Boyce works closely with students and faculty at nearby LaGuardia Community College to provide internships each semester as well as offering tours and hands-on learning opportunities for area high school students. Plaxall is involved with LIC’s arts community and provides the space for Culture Lab LIC, a non-profit arts group that runs the Plaxall Gallery and hosts community programs, performances, and gallery shows. LIC’s diverse mix of large and small businesses are engaged in the community not just in response to today’s crisis, but for the long run.

Centrally located urban industrial areas like LIC show that industry is an important and ever-evolving aspect of a city’s mix. Plaxall and Boyce are not unique in their response to the pandemic, but part of an ecosystem of businesses helping through their expertise and facilities: from caterers and food companies like Neuman’s Kitchen and Juice Press who provided food to healthcare workers and those in need, to 3DBio which also produced ventilators and PPE, to clothing companies that made masks and gowns, a neighborhood equipped to make things is a responsive neighborhood.

The success of LIC in preserving active manufacturing uses serves as a case study for how industrial areas embedded within mixed-use urban neighborhoods allow for collaboration, quick adaptation of supply chains, and creative solutions, which help the region better withstand and recover from future crisis. They can serve as centers of innovation that give birth to new ideas and solutions to urban problems.

Concentrated industry represents not just the creation of everyday essentials but also family-supporting jobs. The average wage of a worker in manufacturing is nearly twice that of a retail worker. Plaxall and Boyce Technologies highlighted above are just two examples of LIC’s industrial and manufacturing sectors that provide jobs at every level, which employ 40% of the workforce in LIC.

In imagining city life after COVID-19, other cities should take from New York and LIC’s example to create and support urban industrial areas that have convenient access to transportation, corporate offices, hotels, residential buildings, educational institutions, workforce training programs, and small businesses. LIC’s thriving industrial sector should remind city leaders that industrial uses are the heart of a modern city. Without support, industrial sectors cannot provide the city what it needs.

Long Island City Partnership (LICP) is the neighborhood development organization for Long Island City. Our mission is to advocate for economic development that benefits the area’s industrial, commercial, tech, cultural, tourism, and residential sectors. The goal is to attract new businesses to Long Island City (LIC), retain those already here, welcome new residents and visitors, and promote a vibrant and authentic mixed-use community. As the designated Industrial Business Service Provider (IBSP) for Queens West under contract with the NYC Small Business Services, we also help foster true industrial uses in the Industrial Business Zone (IBZ) and create new economic opportunities in LIC.

The Post-Pandemic City is a City for Women: Two Ways to Move Towards a More Equitable City for Caregivers

Women on the front lines of the pandemic, at work and at home

While it’s becoming clear that men make up a greater share of Covid-19 fatalities, women and people of color continue to lose their jobs in greater numbers due to the economic slowdown. And both health and economic experts are already pointing out long-term negative effects of the pandemic will be felt most acutely by women and girls.

These inequities rest on a foundation of longstanding economic and health disparities: women, and especially women of color, lag far behind white men in earnings and accumulated wealth, and on average earn just 81 cents for every dollar earned by men. Women in general and Black women in particular disproportionately hold service and sales sector jobs, which have been slow to return. And they make up almost 70% of workers in low-wage jobs that pay less than $10/hourly, with Black and Latinx women overrepresented in those jobs.

Women are more likely to be on the coronavirus front lines in cities. They make up 76% of essential healthcare workers and 73% of government and community-based service workers, and two-thirds of grocery store and fast-food employees. This largely-female workforce risking infection daily to do essential jobs are also more likely to be Black women and women of color, who are already more likely to have a variety of pre-existing or chronic conditions that may put them in a higher coronavirus risk group.

For women with childcare or other caretaking responsibilities, the impact has been bleaker still. With schools and many childcare centers closed, the Covid crisis has exacerbated the existing burden of unpaid labor: caretaking and household responsibilities that women have long shouldered disproportionately in the US and worldwide.

“Up until the lockdown hit, I was consulting 4 days a week. Now, my goal is to have 4 days per month.”

It’s clear that across the socioeconomic spectrum, Covid-19 has forced women’s age-old choice of work or family into the foreground. During a pandemic, this isn’t a theoretical question of “having it all.” Millions of caretakers are facing mental health challenges and long-term financial loss. For many others, it’s a matter of life and death.

As a society, we cannot choose to fail women at this critical moment. This crisis can be a turning point, but only if cities step up and take action on meaningful gender equity policies. Of course, urban policy and planning alone can’t undo centuries of systemic inequity. But by creating policies and spaces that meet the needs of women and caretakers who have long carried a greater burden, it can begin to level the playing field.*

*We also must begin with a caveat about the enormity of the problem: Covid-19 has permanently changed a generation’s relationship to the workplace. There are many consequences of this mass shift in behavior around work caused by Covid-19 that we won’t focus on here, although they remain central to work and mobility for all, not just caregivers. Issues like broadband access, grid capacity, interior air quality, the financing of the MTA, and public education, not to mention affordable housing. These are major systemic issues that deserve a critical overhaul. However, by looking at the daily movement and work patterns of caregivers, we can target relatively simple, actionable solutions that can make New York City, and all cities, more equitable.

Cities for Women

Gender-inclusive design is a nascent but growing practice that begins with including more voices and experiences in the planning process. As the urban policy and design professions confront the historical lack of equitable representation in their fields, and worse, how some well-intentioned practices have exacerbated racist harm, a crisis moment like ours provides an opportunity to right these wrongs. In the face of entrenched inequities like the ones many caregivers face, an inflection point is an urgently needed break in the status quo.

Gender-inclusive design is a nascent but growing practice that begins with including more voices and experiences in the planning process. As the urban policy and design professions confront the historical lack of equitable representation in their fields, and worse, how some well-intentioned practices have exacerbated racist harm, a crisis moment like ours provides an opportunity to right these wrongs. In the face of entrenched inequities like the ones many caregivers face, an inflection point is an urgently needed break in the status quo.

The female experience of urban space has long been colored by the same inequities that touch every other aspect of life, from the gender pay gap to the threat of sexual violence. But as Curbed recently suggested, the Covid-19 crisis could serve as a tipping point to move us toward a “feminist city.” However, our current crisis is just shining a light on the underlying inequities that make the feminist city such an aspirational paradigm. Caregivers have long navigated urban spaces differently, and have done their best to survive and thrive in spaces not designed for them.

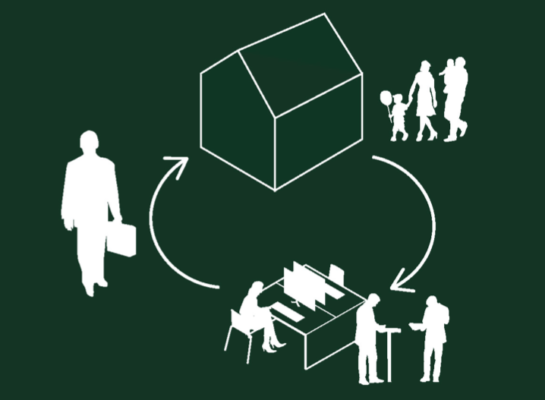

The two aspects of urban life we focus on are work and mobility: specifically, the spatial implications of changed patterns of work, and opportunities to reimagine mobility to better serve caregivers and families. Both are fundamental, every-day aspects of urban life that have been completely upended, both spatially and experientially, by the Covid crisis. And both have a long legacy of failing women, particularly caregivers, and particularly women of color and those with lower incomes. By reimagining how our workplaces function spatially, and how our cities facilitate movement, we can restructure some of the power systems inherent in a built environment that has long ignored the needs and erased the experiences of caregivers.

In addition to the research cited throughout this article and our own experiences, we draw on the experiences of 62 respondents to an original survey about patterns of work and mobility while being a caregiver in NYC during Covid-19. We disseminated this survey through New York City parent email and social media lists in July of 2020.

The “Home Workplace” but Make it Cooperative!

With children suddenly at home, the deeply unequal burden of childcare has grown more unequal. Recent research suggests that unpaid childcare work, not sex-based discrimination, may be the key to the gender pay gap. A 2018 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research puts it succinctly: “Even with perfectly equal pay for equal work, there would still be large gender inequality in earnings as equal work is not an option for the majority of women who are faced with the lion’s share of child care responsibilities.”

“There is joy in the closeness, but I am so tired.”

As many of our survey respondents have experienced, the Covid-19 pandemic has exploded the line between work space, childcare space, and home. As the Washington Post recently put it, “Under various shelter at home orders, every day is Take Your Child to Work Day.” But these lines were already blurring. Enabled by digital tools and platforms, the rise of gig, part-time, and freelance jobs, and more companies offering telework, home-based work has been on the rise for a decade. Covid, of course, accelerated this trend dramatically. A recent MIT study found that of those employed pre-Covid, about half are now working from home, including 35.2% who report they were previously commuting and switched to working from home.

“We relocated to a different state to have access to part-time childcare provided by a family member. We still have major gaps we have to cover.”

For low and many middle-income families and for women who have otherwise chosen to stay at home with children, the lack of affordable childcare has long been a major barrier to work. Lower-income women have long relied more on their “village,” including intergenerational households, but over time planning has made this more difficult by separating not only land uses, but also intergenerational families or co-housing communities, through zoning. The isolation of many mothers across demographics is an important mental health concern that continues to be physically and socially reinforced.

When asked to identify their ideal work situation post-Covid, women who responded to our survey overwhelmingly wanted more flexibility, the ability to continue working from home, extreme reductions in hours in exchange for focused work time, and better local workspace options than before the pandemic. But survey respondents were clear what support they need to make it all work.

“I’m constantly distracted, stressed, juggling too much, and worried about long term economic stability.”

The caregivers in our survey suggest that they will continue to benefit from working from home to manage family and caregiving obligations; however, they won’t be effective, productive, or satisfied in a scenario where they do not have the support of school and childcare. In addition, many women indicated that flexibility alone wasn’t enough, that they needed control to determine their own schedules, and wanted to be assured that the culture of their workplaces recognized the challenges parents face balancing work and home. For many, though, the social part of work is what makes the work itself bearable.

Just as many workplaces shifted to meet the needs of a fully-remote workforce overnight, we should now demand that cities and policymakers support the most vulnerable members of the labor force by helping women in all kinds of jobs to gain more power and control over their hours, schedules, and work locations–as a small step in re-integrating a culture of care into daily life.

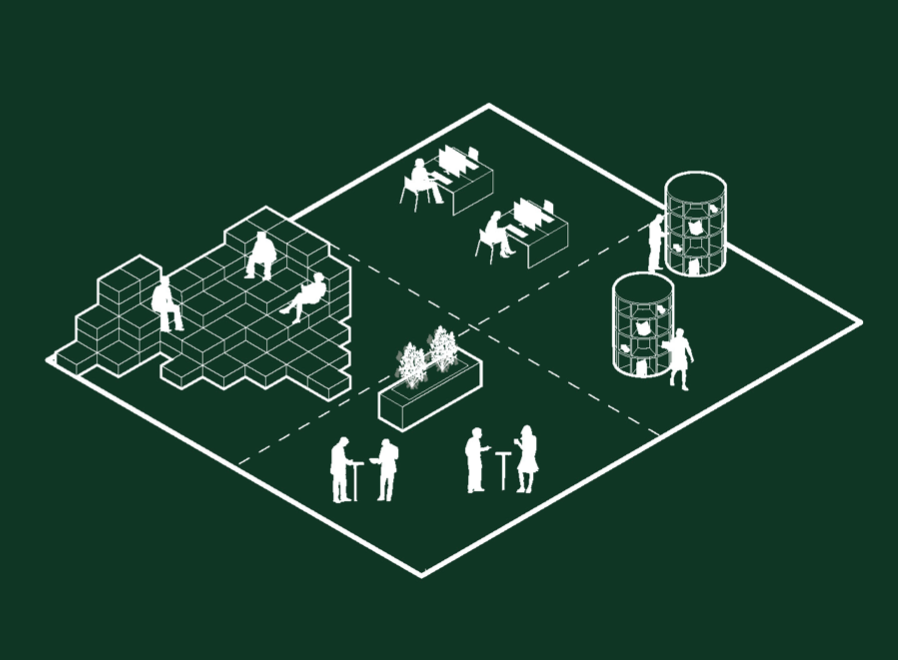

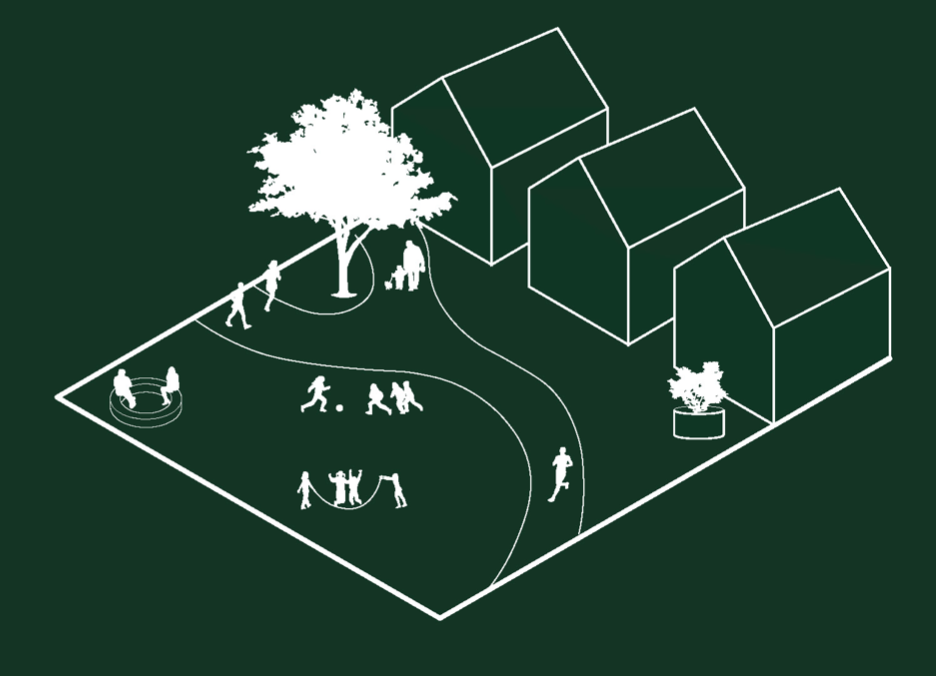

Cities built to center the experiences and needs of female caregivers must have:

- A cooperative, affordable model of childcare that is neighborhood-based

- Safe spaces for children to play, learn, and socialize while their parents work nearby

- Spatial solutions for a non-traditional work schedule and locations

- Support for more inclusive neighborhood-based coworking and community space options that explicitly meet the needs of parents and caregivers, including subsidy and access to public facilities

- Relaxed restrictions and proactive models for multi-family cooperative housing, accessory dwelling units, and retrofitting

Collocated and cooperative models for living, working, and taking care of families aren’t new–nor are such spaces that specifically meet the needs of women. However, affordable, inclusive, and community-led spaces are exceedingly rare in the U.S. A city for caregivers would offer subsidy and technical assistance to create more locally-managed, women-led community work spaces that can sustainably meet work, social, family, and wellbeing needs of caregivers in their own neighborhoods.

Collocated and cooperative models for living, working, and taking care of families aren’t new–nor are such spaces that specifically meet the needs of women. However, affordable, inclusive, and community-led spaces are exceedingly rare in the U.S. A city for caregivers would offer subsidy and technical assistance to create more locally-managed, women-led community work spaces that can sustainably meet work, social, family, and wellbeing needs of caregivers in their own neighborhoods.

As our small survey corroborates, the demand for flexible space isn’t going to slow down. Coworking is a $9 billion global market that is expected to recover from the coronavirus shutdown and show growth by 2023. This moment is an opportunity to rethink what we value from the spaces that accommodate an increasingly flexible workforce. An existing trend that deserves attention is a small but growing number of coworking spaces owned by and/or center people of color. To name a few: The Coven in Minneapolis is an intersectional space that caters to women, non-binary, and trans women. Ethel’s Club in Brooklyn, New York is an intentional community serving people of color, that has creatively pivoted during coronavirus to serve members as a social and wellness platform. New Women Space is a new Brooklyn-based, inclusive, and women-led community organizing space.

People in community organizing and development have long known how to do this work. Worker Centers are examples of social cooperatives or “gateway organizations” that provide training in workers’ rights, employment, labor and immigration law, legal services, the English language, and more. They may offer an inspiring model for dispersed collaboration and advocacy, without the necessity of a physical location. The international Mother Center movement has created hundreds of self-managed, protected public spaces for women and their children to meet informally in community on a daily basis. Building on best practices across a network, mother centers can be based on a tested approach, but customized in real time to the needs of the members and community.

Importantly, any of these models might successfully include cooperative childcare in its services. In-depth work has been done by the Democracy at Work Institute and the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies to map out proposals for how cooperative childcare can work in New York City. While we work toward subsidizing childcare and distance learning, it’s essential that American cities step up with space, funding, assistance, and support. This moment presents opportunity to follow the lead of women, particularly women of color, who have long been “making it work” during and before the pandemic and are the experts in getting things done in their own communities.

I recognize that my family has been fairly fortunate throughout the lockdown, but it has still been illuminating to feel just how little our society supports working parents and caregivers. We found ourselves paying daycare tuition during the height of lockdown just to help keep our daycare center afloat –we had the ability to pay, but it also seems to highlight just how poor the infrastructure is for childcare providers that support working parents and caregivers of young children. Additionally, we feel like we have no good choices facing us when I return to work. We don’t feel entirely comfortable sending our son back to daycare from a health/risk standpoint, but also feel like we have no choice given the demands of our jobs, having a newborn, and for his social/educational benefit. We also know that his teachers are relying on families like ours keeping their kids enrolled in order to remain employed, which feels like an unfair bind for childcare professionals to be in.

Towards Mobility For All

Caregivers move around cities in a unique way. Their travel patterns tend to be more multi-modal as they maximize efficiency. Women, particularly women of color, are less likely to own cars. Their trips are shorter and less routinized, and their stops more frequent, as they care for children while running errands. They are more likely to walk for transportation and less likely to walk for exercise or recreation. The Transportation Research Board found that single parents were disproportionately reliant on public transit, and that it was their childcare duties, rather than income or other economic factors, that caused this reliance.

Meanwhile, our cities are historically built for a very different way of getting around. The consequences of auto-centric urban development are well-documented, from a range of negative health outcomes to racial segregation to loneliness. And while optimizing cities for commuting is a longstanding urban tradition, there’s been a historically narrow definition of what a “commute” looks like: the same, linear trip across a region at the same time, twice each day. This definition, in effect, erases the more varied experiences and unique travel patterns of caretakers. Freeways may be built to get from point A to point B, but transit systems are built, and priced, to do much the same. And this has very real consequences in gender equity: the UK’s Office for National Statistics found that women are more likely to quit a job over a long commute.

“I really hope that workplaces realize that telecommuting is essential for parents with children. While working at home with kids IS stressful, rushing to get them around the city every day is not something I miss. When I am to get things done, I have the time and space to do it. Generally, I think my quality of life is better because I am not rushing through my day.”

“We felt we needed to have a car in case we needed to leave the city quickly. We didn’t want to be dependent on public transportation.”

Transit by any mode is only effective if it feels safe, and there remains a significant divide in the way men and women perceive the safety of the built environment. The UN’s Habitat 3 Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development found that perception of danger in the built environment is a critical hindrance in global gender equality. Safety is the key driving force in the practice of gender-conscious public space design, because unsafe spaces essentially bar women and female-identifying people from participating in the public sphere. Women who are caretakers may be even further attuned to danger, and rightfully so: a safe environment for recreation and socialization as a child appears to be a significant factor in lifelong health outcomes.

Cities built to center the experiences and needs of female caregivers must be:

- Truly pedestrian focused, where lack of car ownership is no longer a marker of second-class citizenship, and walking is as dignified, convenient, and safe as driving. (Beyond immediate physical safety, a recent study in American Psychologist found growing up in a walkable place was correlated to higher earning power later in life.)

- Not just transit-oriented, but built to facilitate varied, short trips with many stops in a way that is both convenient and affordable, such as offering distance-based pricing rather than a flat trip rate.

- Built for multi-modal trips while carrying children, strollers, groceries, and other trappings of the caregiver’s daily routine.

Fortunately, the coronavirus crisis and the related rethinking of built-environment priorities brings with it some key opportunities to make strides towards a mobility that is truly caregiver-friendly. We must at long last rework our streets to calm traffic and offer more and safer pedestrian routes in all communities, as Paris and other cities are doing. We must prioritize buses and dedicated busways city-wide. Buses are not just disproportionately used by women, people of color, parents, and lower-income New Yorkers, they also offer a safer public transit alternative than subways as the city reopens (in New York, bus ridership has rebounded much faster than subway ridership after the peak of the crisis in April 2020).

Fortunately, the coronavirus crisis and the related rethinking of built-environment priorities brings with it some key opportunities to make strides towards a mobility that is truly caregiver-friendly. We must at long last rework our streets to calm traffic and offer more and safer pedestrian routes in all communities, as Paris and other cities are doing. We must prioritize buses and dedicated busways city-wide. Buses are not just disproportionately used by women, people of color, parents, and lower-income New Yorkers, they also offer a safer public transit alternative than subways as the city reopens (in New York, bus ridership has rebounded much faster than subway ridership after the peak of the crisis in April 2020).

Beyond expansions of existing safe streets programs and growing the bus network, now is the time to think on an even bolder scale. There is a growing chorus of urban thinkers advocating for universal free transit as a basic right. Such a policy would disproportionately improve access to economic opportunity for women and people of color. And cycling advocates have long called for cities to prioritize safe cycling infrastructure so that cycling becomes a legitimate transportation option for women and families, reducing reliance on both cars and public transit. There is proof of concept: Both of these ideas have been successfully implemented in many other cities, where political will didn’t need a crisis to reach a groundswell.

Of course, bold or incremental, these improvements need to be prioritized where they will make the greatest impact: on neighborhoods with a disproportionately greater share of single, working class caregivers, especially women of color. Access to a safe, reliable form of mobility is key not just to economic recovery, but to economic survival in a post-Covid world. It’s time to stop overlooking the experiences and needs of caregivers.

Conclusion

The Covid crisis has both laid bare and exacerbated longstanding inequities in the way we experience and move around the places we live. For many, it has shifted the workplace into the domestic space, blurred lines between paid and unpaid labor, and restricted mobility. It has made being a caregiver, an already burdensome job, more difficult, particularly for those who already face systemic oppression. It is difficult to overstate the misery it has caused.

But the pandemic has also forced an inflection point; the sheer magnitude of its economic and social destruction is clear to nearly everyone (the willful ignorance of certain leaders aside). And with this almost-universally-acknowledged inflection point comes a rare opportunity to reimagine some of the fundamental systems that have led to our entrenched inequities: how we work, how we move, how we care for each other. What we are experiencing is a once-in-a-lifetime will to change. It may even be the beginnings of a true political realignment.

Will we squander the opportunity to build more equitable cities that truly meet the needs of all residents, in particular those who have been left out for so long? The answer rests in the ability of planners, designers, and decision-makers to approach solution-building with open hearts and open ears. Caregivers are well-versed in making do with the inconvenient bare minimum, and adapting systems not designed for them to basic functionality. They’re resourceful, perceptive, and the very definition of hard-working. It’s time to let them lead.

Note:

We use women not to reinforce a gender binary, but rather to understand its effects on a diverse group of people. In this article the term women refers inclusively to anyone who identifies as a woman or with the female gender. This might include people who are cisgender, transgender, non-binary, or anyone who has a female gender expression.

Survey Insights ↓

To ground our qualitative research, we captured some additional data from our respondents. Here are a few highlights:

62 people responded to the survey. Of these:

- 60 respondents were caregivers of children, with an average of 1.6 children per household, with household sizes ranging from 2-6

- 83% of parents were married and living with a spouse, and another 6.7% lived with a partner

- Nearly half (46.8%) had children under 3 years old, and another quarter (27.3%) had children between 4-6 years old. 9.1% had older teens age 14-18

- All identified their gender as female or non-binary/third gender, and a majority of the partnerships described in the research were hetero relationships

- All respondents were over age 30. Most were between 35-40 years old (39%) and 40-50 (37.3%)

- 73.3% of respondents identified their race or ethnicity as White, 10% Black or African American, 5% Asian, 3.3% as Latinx or Hispanic, and 8.3% as Other*

Employed women across the economic spectrum are carrying a dual burden of managing stressful situations at home while also navigating exacerbated workplace stress caused by coronavirus. Only about 10% of respondents to our survey said they were “not at all concerned” about their employment status. 55% said they were very, highly, or extremely concerned about their employment status.

On the whole, the women we surveyed earned good, middle and upper middle-class incomes (when working) and represented a somewhat diverse economic range. 16.9% earned over $200,000, 35.6% earned between $100-200,000, 28.8% earned between $70-100,000, 13.6% earned between $50-70,000, and 5.1% earned between $20-50,000. No respondents selected the option provided for incomes under $20,000.

Only about 14% of survey respondents expressed an explicit desire to return to a full-time office schedule. Several of these respondents shared that returning to an in-person workplace is important for the work they do–teaching, non-essential healthcare professions, roles with physical job sites.

Respondents voluntarily opted into participating in this survey, which was distributed digitally through social media channels, with a focus on reaching local NYC parent Facebook groups and email lists. The survey was conducted in July 2020.

*Due to a form error, respondents could only choose one race/ethnicity category.

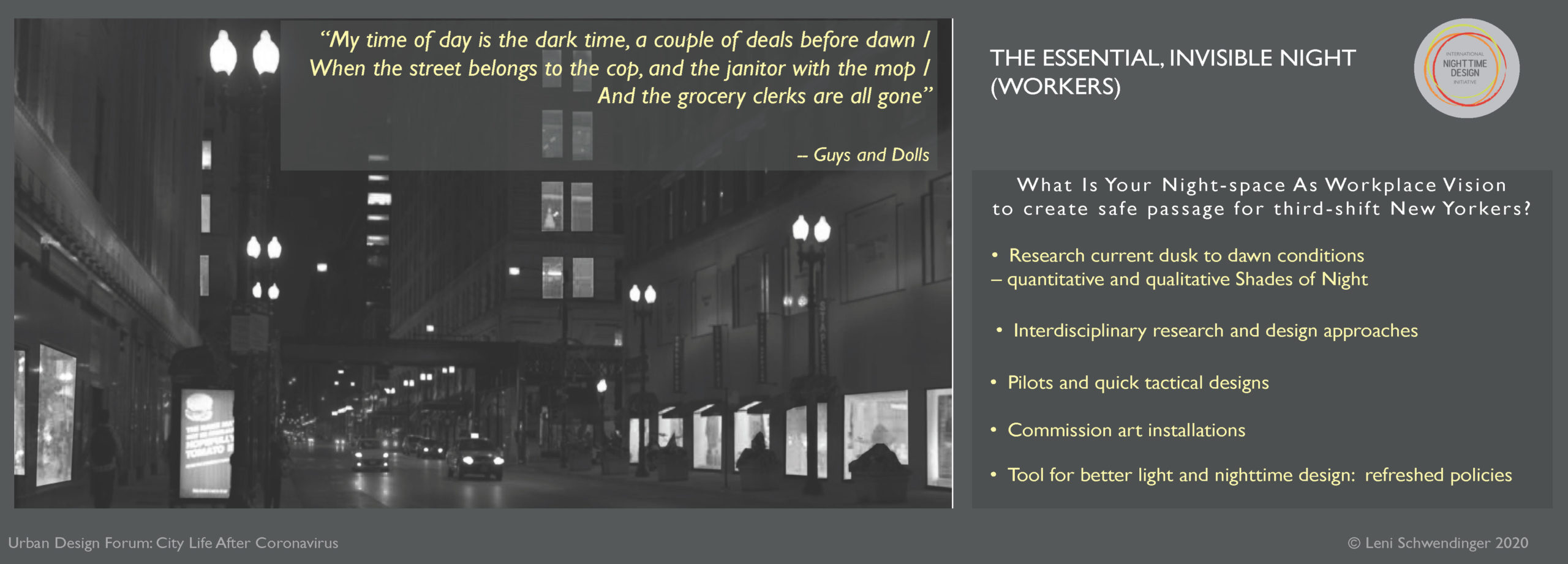

The Essential, Invisible Night: Illuminating Cities for Essential Workers

The architectural and urban design professions are day-biased, even as night is a full 50% of the world’s time. My years of work as an urban lighting designer have expanded to propose an interdisciplinary awareness of night as place.

Nighttime design is a long overdue area of study and implementation. Holistically applied it could directly affect physical -and mental –health, and safety, for “essential” nightshift workers by focusing on legibility and late-night services. In this paper, the various categories of night work are used: shift-work is an overall term to differentiate from the normative day-shift. Other terms are, for example, night-shift, second-shift, third-shift and graveyard shift. Second (or evening) shift starts around 2 to 6 p.m. and ends between 10 p.m. and 2 a.m. Night-shift (or third or graveyard) starts around 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. and ends around 5 to 8 a.m.

This think piece targets issues that have existed before and during the pandemic. However, because of the pandemic, I posit that a relevant synergy between “essential” “worker” and “night” remain cynically unaddressed. While the city and state of New York has lauded (and applauded) those of us who work tirelessly to keep the wheels of society and commerce turning. At the same time, it is disingenuous to avoid consideration of public-space working conditions that are critical to our key workers, that is, the hours between dusk and dawn.

Why is this important?

From the outset, night-shift workers’ conditions are inequitable. Per U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 18% of the 11-million service workers in the protective, food, and cleaning sectors work the evening and night shifts. And, significantly, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health states that “Both shift work and long work hours have been associated with health and safety risks.” Additionally, shift work is associated with diet-related chronic conditions such as obesity and cardiovascular disease, per “Influences on Dietary Choices during Day versus Night Shift in Shift Workers” (from Nutrients 2017). These are but two salient studies.

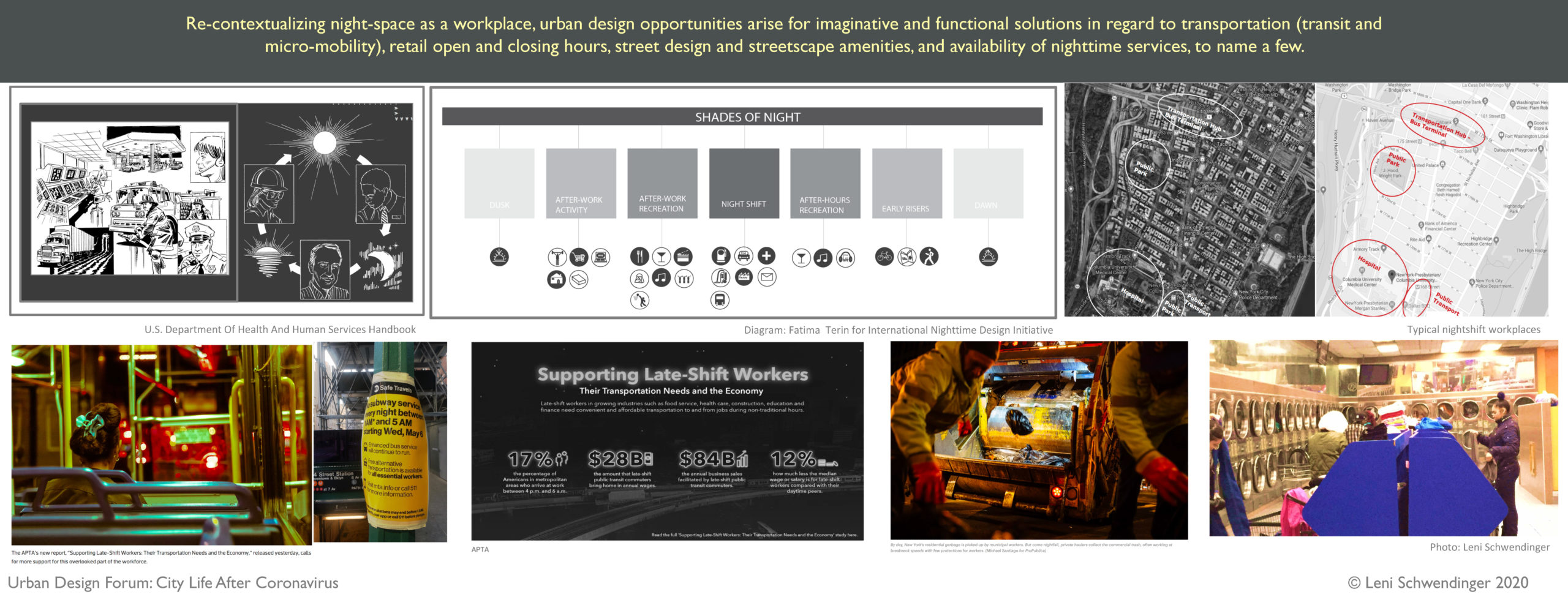

Thus, re-contextualizing night-space as a workplace, urban design opportunities arise for imaginative and functional solutions in regard to transportation (transit and micro-mobility), retail open and closing hours, street design and streetscape amenities, and availability of nighttime services, to name a few.

Further to understanding the plight of the graveyard shift population, the seminal 2009 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 30-page document, “Psychological and Social Support for Essential Service Workers During an Influenza Pandemic” addresses both the psychological and social needs of essential service workers during a pandemic. The authors define these workers to include “healthcare workers, public health workers, first-responder organizations, and employees of public utilities, sanitation, transportation, and food and medicine supply- chain companies.” All of these key workers are likely to be employed on second and third -shift work.

Equity issues are involved, as the New York State essential-worker definition expands upon the CDC’s, and includes not only the professional classes but also those who take care of our mail and shipping, laundromats, building cleaning and maintenance, childcare services and warehouse jobs. All of these roles have nighttime shifts, and are so-called “low-skilled” or blue collar. UCLA’s Neuropsychiatric Institute’s Dr. Carole Lieberman, indicates that “Night shift workers begin to feel like second-class citizens. They begin to feel invisible.” There is a diagnosis for those who cannot adjust to changes in the sleep/wake cycle, or circadian rhythm: Shift Work Disorder. Symptoms include sleepiness, often coupled with insomnia and depression.

In addition to the individual Disorder symptoms, described above, extrinsic, gender-based, night-space brutality is a facet of daily life for women. Design, from a harm reduction point of view, can begin to address the darkened work and mobility environment, as briefly enumerated below.

International Labour Organization co-authored with UN Women’s “Handbook: Addressing violence and harassment against women in the world of work”, repeatedly enumerates that traversing the city to and from home and transit, is dangerous for women, especially in regard to sexual harassment and assault, “particularly affecting women working shifts and having to travel by foot or public transport in the dark or late at night. Preventative actions by local authorities – such as improving street lighting or the positioning of bus stops – can have a beneficial impact on making women’s, as well as men’s, lives safer when they commute to work.”

Design Solutions:

We suggest that districts with a preponderance of shift workers and neighborhoods with night work sites, such as hospitals, transportation and transit hubs and warehouses be designated night zones in order to benefit from night-focused interdisciplinary design solutions.

For example, consider the northeast section of New York City’s Bronx, a future recipient of a Metro-north transit line. This district contains a preponderance of 24-hour work sites, including more than nine hospitals, one of the largest food distribution centers in the world, and nearby, the George Washington Bridge Bus Station with connections for transit riders during the dark morning and evening hours, as well as 24-hour drivers starting and returning to the Bus Station itself.

Fearful nighttime conditions can be ameliorated and turned positive with creative design collaboration inclusive of architectural disciplines, landscape, illumination, wayfinding and security. New approaches to nighttime design would focus on lighting and legibility for first and last mile transit corridors, enhanced bus stops for late night ridership needs, and public space amenities for shift workers adjacent to workspaces.

Typical design tactics, starting with existing conditions studies are relevant. For example, a Shades of Night analysis, which is a framework to measure human activity in relation to environmental changes such as open-shut hours and lighting should be undertaken to characterize after-dark populations, their movement and needs. Consultant teams for nighttime design must be assembled to address shortcomings of the district. Which consultants can address safe meeting places? How about availability of food purveyors, including food trucks? Are night transit options that relate to local worksites in place? What about after-dark cultural offerings and protected public spaces, such as all-night libraries? These are experts in addition to the ones already mentioned, such as those well versed in permitting, sustainability, community engagement and real estate, among others.

For rapidity, tactical urban and lighting solutions could be devised in the form of measurable pilots that would be planned as participatory exercises that concurrently build community capacity in the self-same districts. Longer term, smart technologies are available to enhance amenities and wayfinding.

Let’s value essential, heretofore invisible, shift-workers as they work and traverse the dark city by establishing welcoming, safe public spaces.

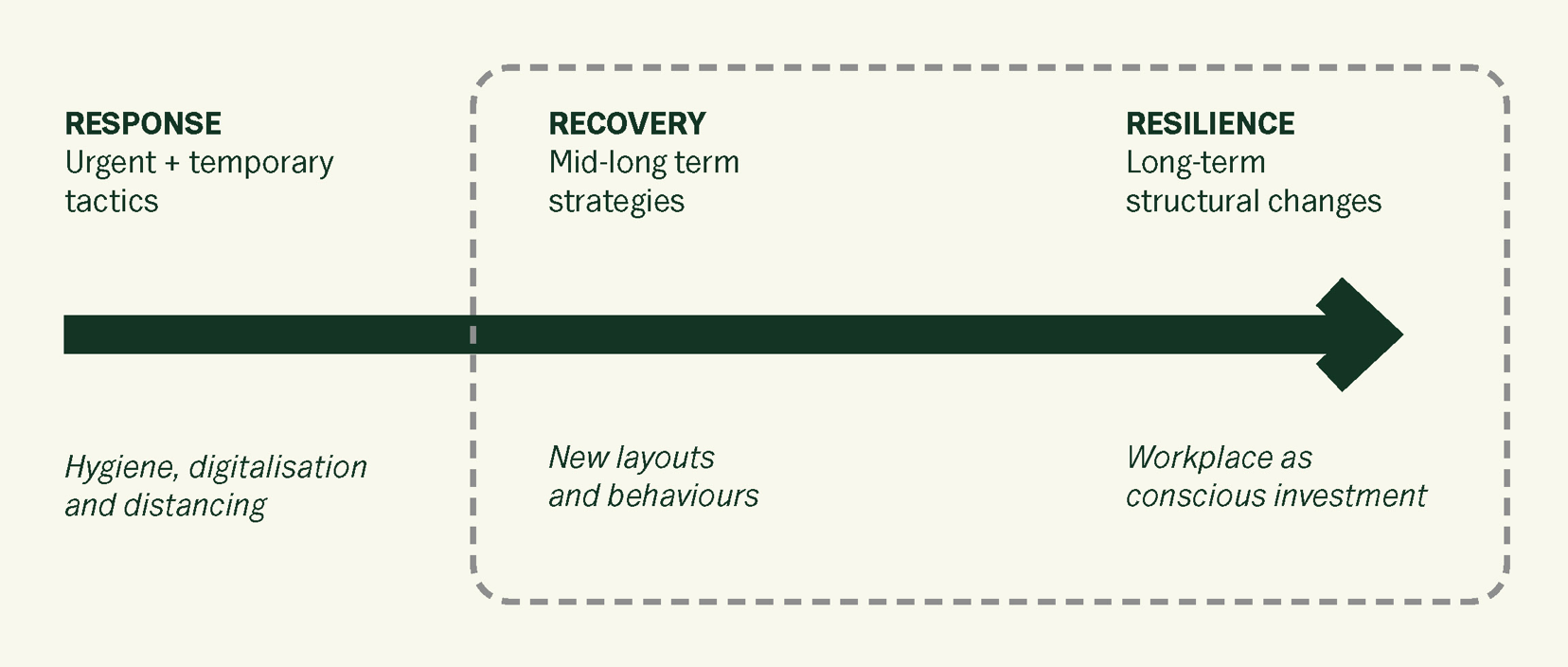

Using Behavioral Science as Design During COVID

Envisioning a Post-COVID 19 Workplace

Design Drivers

- Flexible Working:

- Embrace of remote working

- Staggering shifts

- Blurring of work-life

- New metrics for locations

- Missing Each Other

- Lack of social interaction

- Loneliness

- Face to face need for training and learning

- Barriers to innovation

- Need for a sense of belonging and spontaneous interactions

- Hygiene and Safety

- Reversal of densification trend and hot-desking trend

- Mixed perception of textiles

- Lifts and VT as chokepoints

- Uncertainty over shared spaces

- Anxiety over cleanliness and personal space

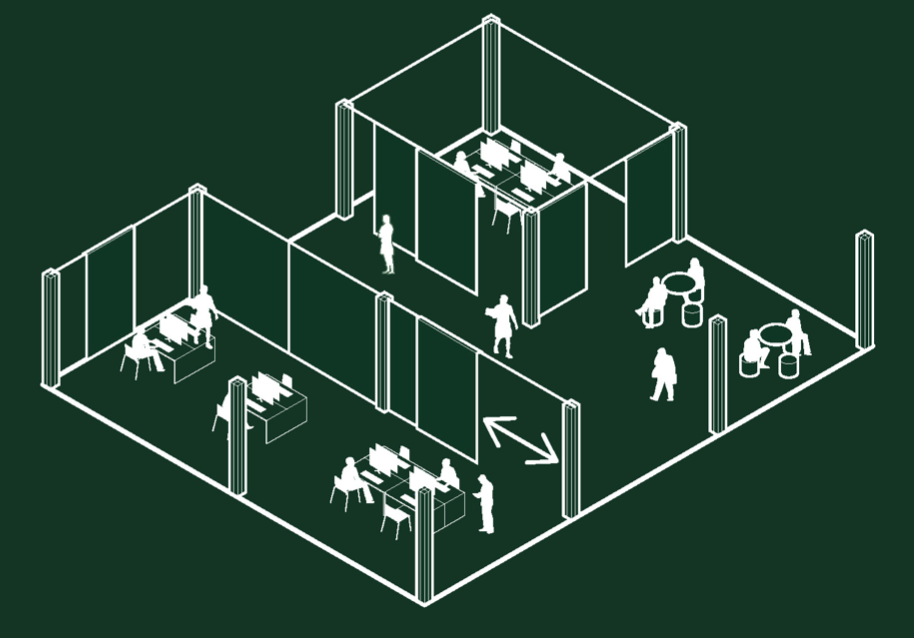

Nine Design Responses

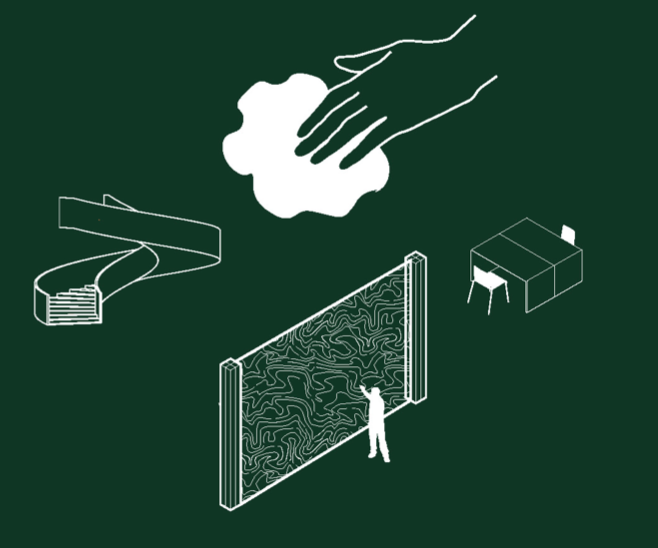

Agility

- ‘Dancing’ walls an furnishings

- Design for disassembly

- Design for flexibility

- Multiple modes of inhabiting and overspill areas

Office as Resource

- Social event space and high-end amenities

- Learning and training spaces

- Collaboration and workshop spaces

- ‘Genius bar’

Neighbourhoods

- Clusters of around 20-25 people

- Sense of trust and familiarity

- Agreed social rules and sense of belonging

- Ability to compartmentalize

New Routes to Innovation

- Analogue-digital hybrid spaces

- Emotive design to stimulate

- Cross views

- Fostering communication

Expression of Values

- Reciprocal flexibility

- Club membership

- Communicate brand and ethics

- Placemaking

Cleanability

- Contactless, hands-free tech

- Easy to clean and maintain surfaces

- Self-disinfecting, antibacterial materials

- ‘Mudroom’/’bootrooms’

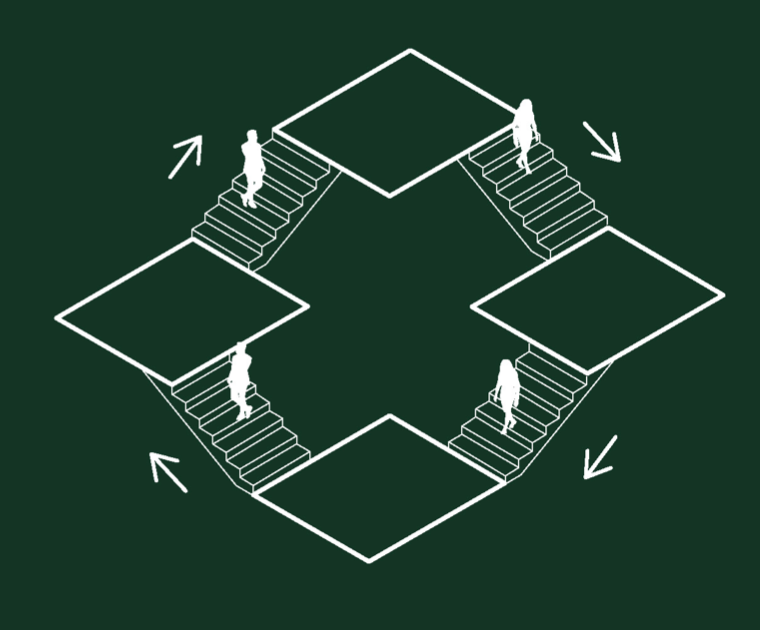

Choreographing Movement

- Redesigned, oversized entrances and lobbies

- Sensoring and machine learning

- Clarity of wayfinding and more stairs

- Compartmentalization

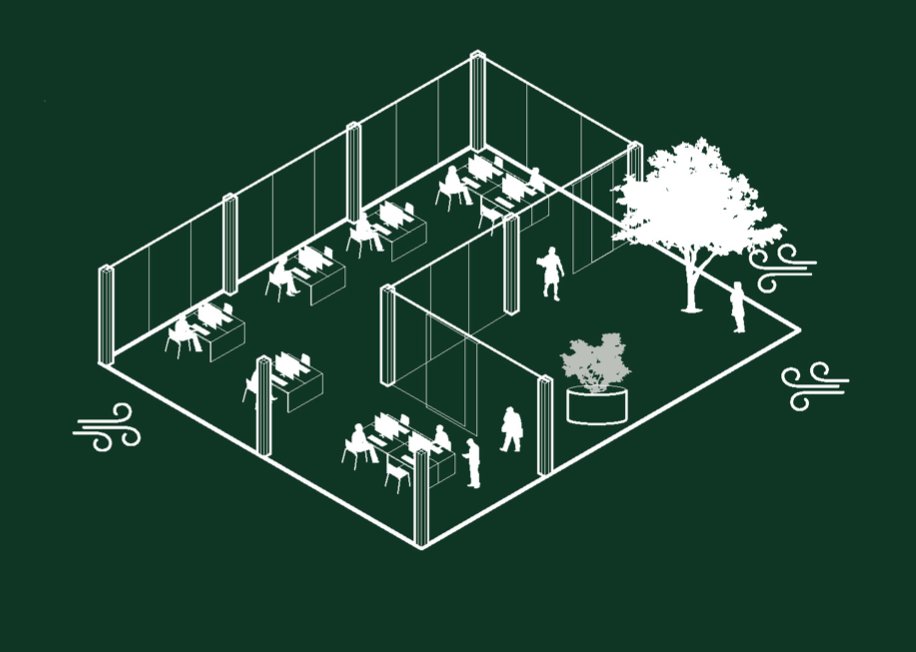

Access to Air

- Natural ventilation and outdoor spaces

- “The jumper concept”

- Upgraded HVAC for daily flush

- Green Lungs

Sensorial Comfort

- Biophilia, textures, and natural materials

- Daylight and smart light

- Ability to withdraw

- Savannah theory

We are 3XN Architects. We believe that architecture shapes behavior. This informs all our work as we continue to explore ways for enriching the lives of people.