City streets became sites of escape for residents under lockdown. People fled to parks and beaches, emphasizing the importance to accessible and well-maintained green space in the built environment. Additionally, businesses expanded into the streets for distanced outdoor dining. Outdoor space has new meaning, but how do we make it equal for all residents? These proposals explore ways to engage the public using open spaces and ways to integrate social distancing into street planning. Scroll to see all 10 proposals.

Street Dining Pavilion: Exploring the Design Capabilities of Social Distancing

Transforming City Streets Into Green Spaces

Distance Dining: A Reopening Toolkit

Integrating Social Distancing into Street Planning

Exploring the Role of Parks as Community Recovery & Resilience

Responses Continued ↓

A Blueprint for Shared Summer Streets in Hudson by Liz McEnaney, Anna Dietzsch, and Kaja Kühl

Distance Dining: A Reopening Toolkit by Tiya Gordon

Integrating Social Distancing into Street Planning by Catherine McVay, Patrick Kennell, Kate Ascher, and John Messengale

Exploring the Role of Parks as Community Recovery & Resilience by Victoria Cerullo

Shifting Perspectives on Street Life by April Schneider and Haikun Xu

Inside Out: A Case Study for Improving City Streets by Peter Martin and Kevin Alexander

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Urban Design Forum launched City Life After Coronavirus, a digital program convening Fellows and international experts to document global responses to the current crisis and to strategize a road to recovery for New York City. In April, we released a Call for Ideas to our network soliciting a broad range of submissions that envision how urban planning and design should change in the wake of Covid-19 as we strive to build a more just city for all New Yorkers. We are featuring some of the most compelling ideas in a series of reflections and proposals about diverse topics like education, community engagement, and mobility. Explore the full Gallery of Urban Ideas here.

People's Pocket Park: Main Streets as a Center of City Life

CUBE, Climate Urgency in the Built Environment, proposes the People’s Pocket Park (P3) – a multi-phase kit of parts informed by community input – reimagining our main streets as the center of city life.

The COVID-19 pandemic has transformed how we work, live, and interact with our environment. Proximity to outdoor space has never been more beneficial. Urban residents have become increasingly reliant on and engaged in their immediate neighborhoods, with public transit options reduced, socializing outdoors, and increased time in the home. In March, New Yorkers experienced a driverless NYC. With parks closed, we played on the sidewalk and walked in the street. Why, in the past, has unsafe, loud, and polluting vehicular traffic taken over our streets? In the wake of the pandemic, the City of New York must replace car and subway congestion with green infrastructure, such as cross-borough bike transit, bus-only lanes, and pedestrian streets.

NYC’s initial rollout of Open Streets and Open Restaurants is a step in the right direction, but the implementation of these programs and their distribution lack foresight, equity, and proper management. Despite the shortcomings of these government programs, they have displayed NYC’s ability to respond quickly to a social and economic crisis. We must channel this energy towards the longevity of an equitable and sustainable future. Our city is in urgent need of creative solutions and political support that invests in the dignity of our most vulnerable communities.

The People’s Pocket Park (P3) is designed for neighborhoods that have disproportionately borne the brunt of the pandemic as a result of longstanding economic neglect, poor air quality, and a dearth of outdoor space. P3 is a phased prototypical strategy that permanently implements green streets in a manner that is commercially viable, as well as pedestrian and environmentally friendly. Upon installment, each Pocket Park would introduce roughly 4,000 square feet of additional outdoor space available for commercial and public use. The scheme is adaptable to any urban corridor, with the exception of those along a bus route. P3 invites communities to shape their built environments. The People’s Pocket Park provides a space safe for pedestrians with improved air quality that nearby residents can personalize through public programming of their choice.

“The more successfully a city mingles everyday diversity of uses and users in its everyday streets, the more successfully, casually (and economically) its people thereby enliven and support well-located parks that can thus give back grace and delight to their neighborhoods instead of vacuity.” – Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

For the vitality of our neighborhoods, a reimagined streetscape becomes critical to ensure passersby feel safe and comfortable, social distancing guidelines are maintained, and local business can continue to operate and flourish. P3 fosters cross community interactions in outdoor spaces.

In order to achieve the longevity of Open Streets, our streets must be:

- Good for business

- Safe for pedestrians

- Environmentally friendly

- Conducive for commercial deliveries.

In addition, infrastructure like storm drainage, garbage collection, bus routes, and access to fire hydrants must not be disrupted.

The implementation of P3 is broken down into three phases to allow for sustained effectivity in the event of gradually available funding.

Phase 1 calls for the removal of parking, conversion to one-way streets, and the installation of temporary ramps to receive deliveries.

Phase 2 replaces the temporary ramps with curb cuts and invites the community to paint murals using the new public space as their canvas.

Phase 3 involves excavation, planting, and the installation of bioswales. Grass provides large permeable surfaces while trees grow to protect pedestrians from traffic and provide shade.

P3 is an adaptable kit of parts that is informed by community outreach. The process empowers neighborhoods to shape their built environments while reaping the social, environmental, and economic benefits of green infrastructure.

Project Leads: Antonino Boornazian, Madeleine Reid; Project Team: Natalie Bartfay, Braham Berg, Ira Gamerman, Diksha Jain, Tom Redstone, Matthew Sheridan, Abigail Thomas

CUBE | Climate Urgency in the Built Environment is a coalition of young climate activists passionate about climate urgency in the built environment. With roots in the Sunrise Movement, CUBE works with climate advocacy groups to promote a Green New Deal, which will create resilient cities and clean economy jobs.

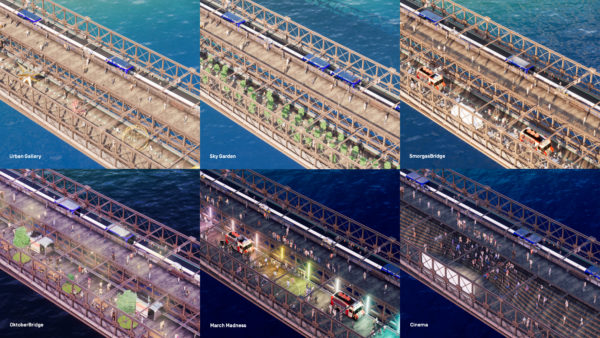

Back to the Future: Reimagining Brooklyn Bridge

Back to the Future seeks to return the bridge to its original iconic state, both architecturally and functionally, and pilot innovations in autonomous mobility and public space design. By removing cars and related ramps, and providing more space for pedestrians, bikes and transit, the bridge will move more people and create a stronger, more sustainable, and more equitable connection between Downtown Brooklyn, Lower Manhattan, and beyond.

Prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic and demonstrations against police brutality, the Reimagining Brooklyn Bridge competition brief required streets and shared spaces to address the present moment and past injustices, and to enable peaceful gatherings, safe transportation, a healthy environment and opportunities for small businesses to flourish.

By restoring the bridge to its original design accommodating public transit, walking and public realm, the Back to the Future proposal re-invents one of the most visible icons in the world. The proposal expresses the transformation of our city streets and infrastructure for people and places first, while we manage automobility to be less intrusive, and bring the bridge into the 21st century. The original Brooklyn Bridge anchorages and their surroundings were integral parts of the neighborhoods they connected, with significant public transit facilities, public spaces, and even commercial spaces within their structures. 1950s vehicular infrastructure supplanted these civic features, and forms a barrier for adjacent neighborhoods.

The Back to the Future approach would restore the anchorages to their original form, allowing for public activation, engagement with, and new appreciation of the incredible historic structures. 1950s-era rampways could still be preserved in segments by creating elevated greenways for additional pedestrian access to the bridge, while preserving a visual timeline of the bridge’s urban history.

Removing these ramps would release 32 acres of land for public and environmental benefit on both sides of the bridge, more than 5x the total area of the Highline, to combat climate change and urban heat increase, and offer recreational spaces for adjacent neighborhoods and a growing city.

Today the bridge doesn’t meet users’ needs and some—particularly cyclists and walkers—are especially affected. We want to create a remarkable mobility experience for all New Yorkers, that is more than a piece of infrastructure, but an incredible experience. That said, many New Yorkers still do get around by car for critical functions. The proposed multi-modal design imagines a gradual shift away from private vehicles to release space for pedestrians and bike access across the bridge over time.

Our travel behaviors have changed in the past decade. We continue to move robustly towards cycling, walking and more efficient mobility systems. In response, as new mobility systems and technologies emerge, the bridge can adapt and accommodate a range of mobility scenarios and universally accessible needs. Community engagement should be undertaken at each step of the way to align on the best path forward. So while seemingly radical, the Back to the Future is possible today, and implementable with phased interventions over time.

BIG is a Copenhagen, New York, London and Barcelona based group of architects, designers, urbanists, landscape professionals, interior and product designers, researchers and inventors. The office is currently involved in a large number of projects throughout Europe, North America, Asia and the Middle East. BIG’s architecture emerges out of a careful analysis of how contemporary life constantly evolves and changes.

Arup is the creative force at the heart of many of the world’s most prominent infrastructure, planning, and construction projects. We offer a broad range of professional services that combine to make a real difference to our clients and communities.

Street Dining Pavilion: Exploring the Design Capabilities of Social Distancing

“A new design genre was born last month when New York City began allowing restaurants, which had been closed for on-premises dining since March, to take over miles of sidewalks and streets for outdoor seating… These oases, surrounded by plants and shaded by wide umbrellas, have temporarily transformed the city….The promise of these outdoor cafes is a few hours of relief from our well-founded fears.” – Pete Wells, New York Times

Introduction

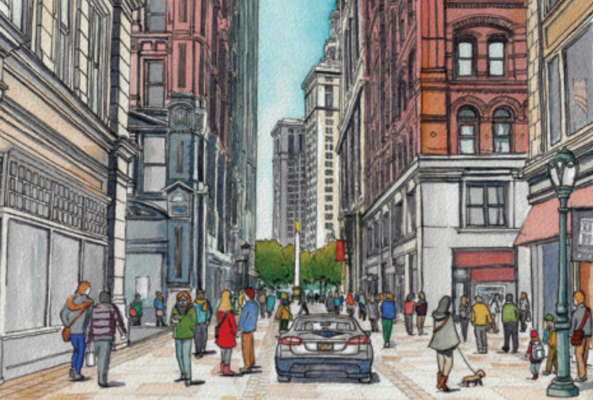

In the past few weeks, encouraged by loosened city restrictions, thousands of restaurateurs across the five boroughs of New York have introduced outdoor dining on converted sidewalk and street areas adjacent to their indoor spaces, which remain off-limits due to concerns about spread of the COVID-19 virus. The result has been a vibrant and lively transformation of the streetscape amidst an otherwise dark and unhappy moment in the city’s life—not only bringing new energy and vitality to the city’s public spaces, but also restoring economic life (and with it, a range of employment opportunities) to the city’s crucial but battered hospitality industry.

Another idea: Put everything outside. Some American cities…have done just that, by announcing the closure of streets to free up outdoor dining space for restaurants. But for many cities, wide-scale al fresco dining is unrealistic… because we can’t ask the weather to stop. There will be snow…wind…and rain…An open-air restaurant is a lovely thing, but ceilings were invented for a reason. – Henry Grabar, Slate

The Concept

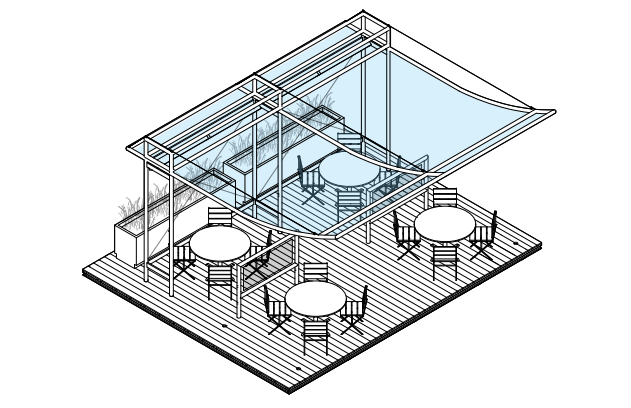

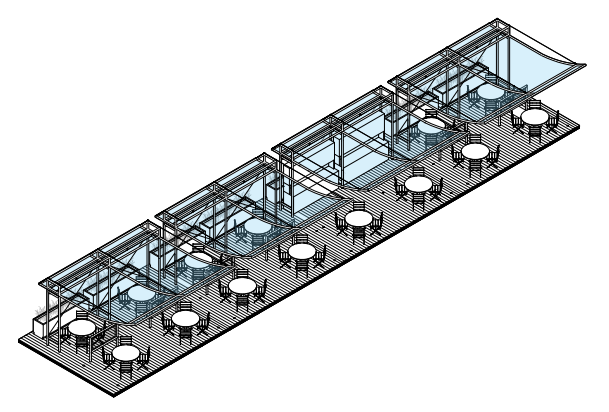

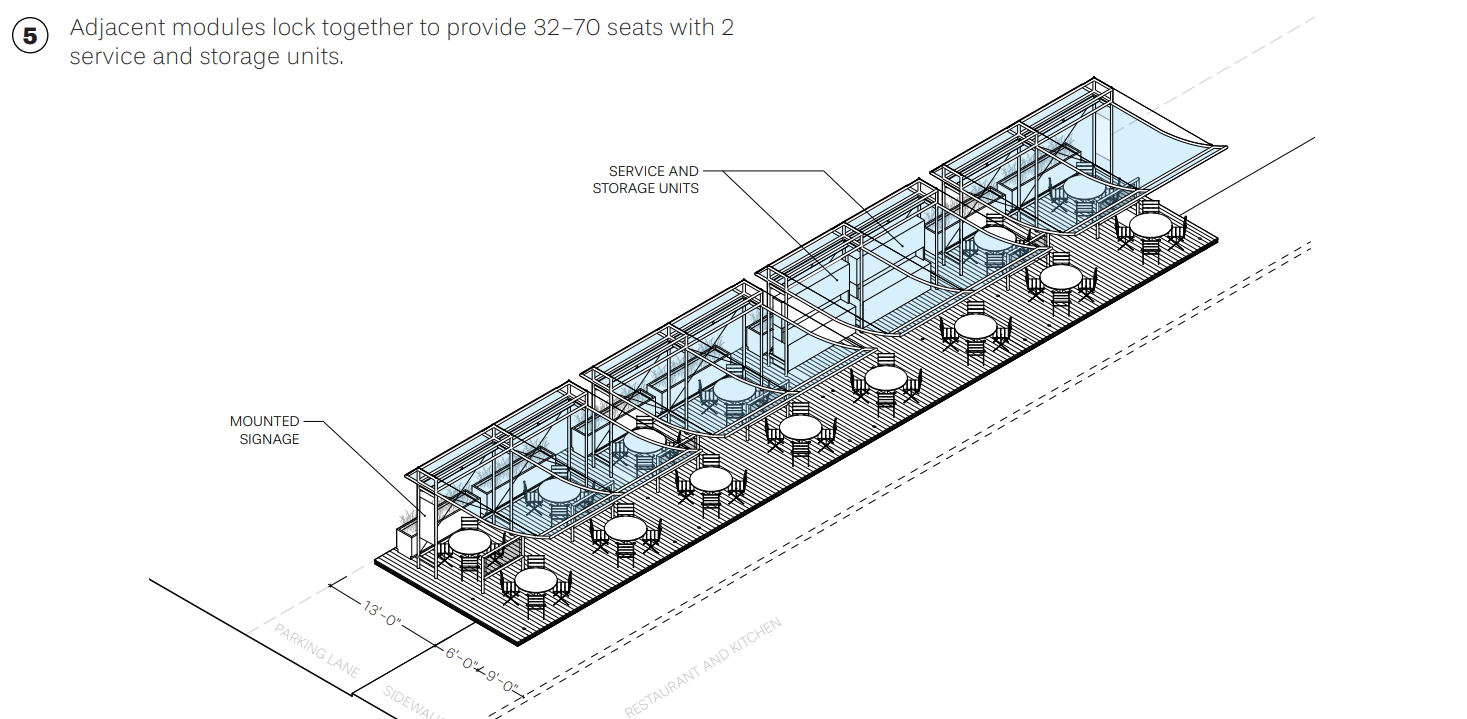

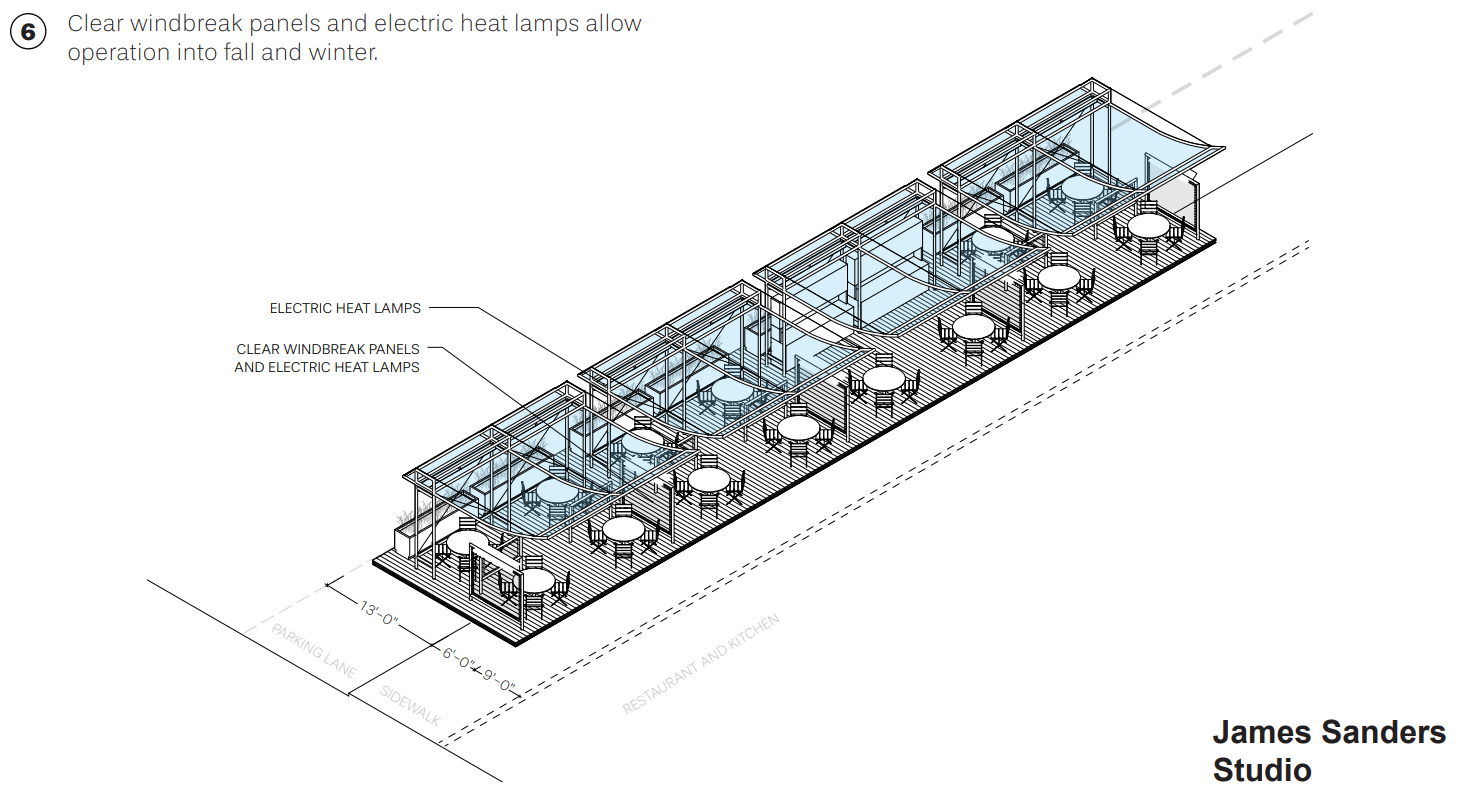

The Street Dining Pavilion—initially proposed in March 2020, before the current trend took hold—is a demountable, “kit-of-parts” installation designed to encourage and expand urban outdoor dining by providing a full fabric canopy roof to allow extensive protection for diners from rain and sun, more convenient operation for restaurant staff through the provision of outdoor stations and storage, and an extended opening schedule that can continue through the fall and winter, through the use of windbreak panels and electric heat lamps, integrated into the canopy structure and decking.

The pavilion occupies a parking lane and adjacent section of sidewalk, providing a curbside dining experience, looking back toward the sidewalk, not unlike the famed cafes of Rome’s Via Veneto.

The Street Dining Pavilion builds on architect James Sanders’ longtime interest in the use of canopy and kiosk structures for outdoor activations. In the early 1980s, for The Parks Council, a civic advocacy group, he and a colleague designed and built an open-air bookmarket, flower market, and two cafés in Bryant Park to revitalize the then-troubled landmark space behind the New York Public Library, the new amenities quickly brought the public back into the park, transformed its use, and initiated the long-term restoration that followed.

More recently, in 2010, Sanders and Pentagram’s James Biber collaborated on Riverways, a proposal for a system of low-cost floating recreation docks along the Hudson River, employing matching canopy structures and kiosks to shelter activities and provide a highly visible marker of the new linkages between land and water.

“Governor Cuomo and Mayor De Blasio have wisely held off letting restaurants operate indoors, where diners are at the mercy of unreliable air-conditioning systems. If, come cooler weather, distrust of the great indoors persists and restaurants can’t lure customers back into their dining rooms, New York should invest heavily in heat lamps, emulating Northern Europe’s virtually year-round outdoor dining culture…” – Justin Davidson, New York magazine

The Design

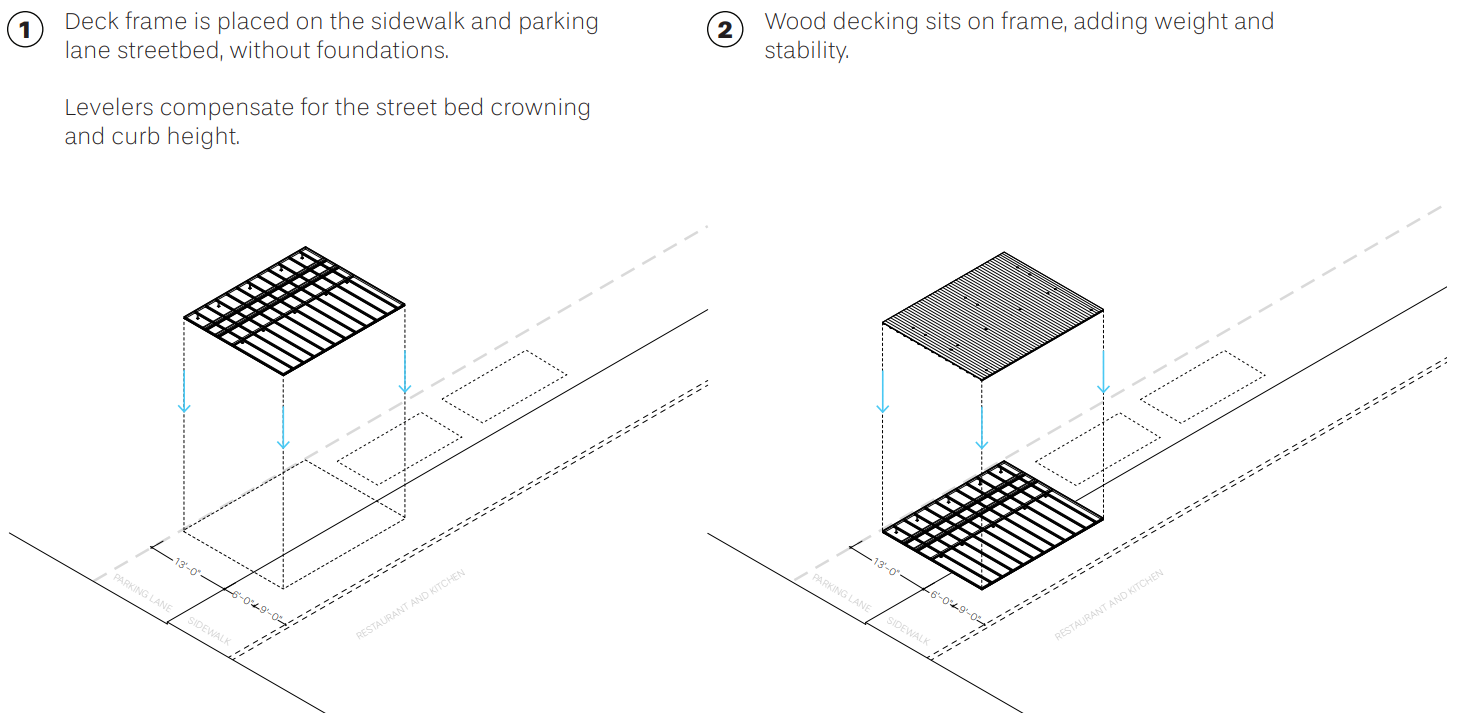

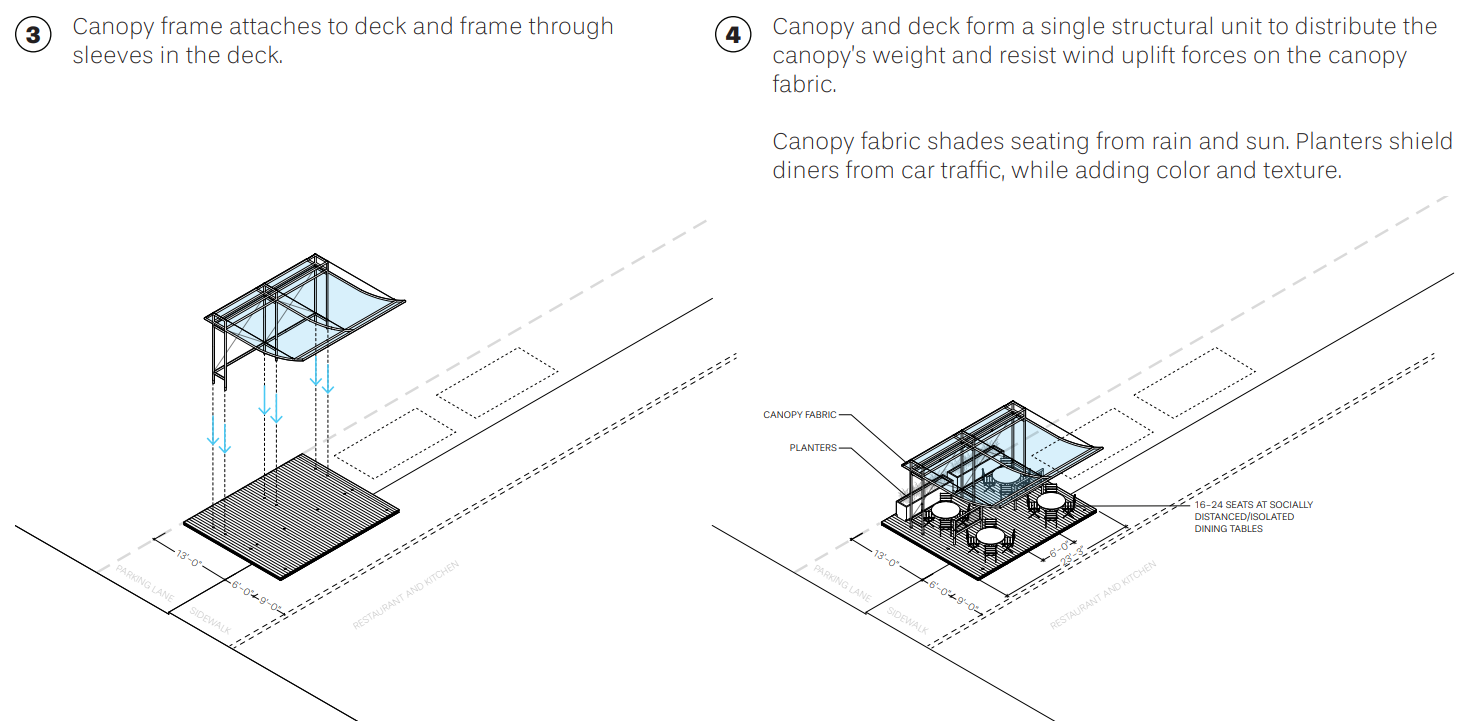

The installation consists of a wood slat deck that “floats” a few inches above the street and sidewalk (with adjustable levelers to account for uneven surfaces), on which sits a fabric canopy to provide rain and sun protection for the tables below. The structure also accommodates heat lamps, clear windbreak panels, and lighting, allowing for continued use in colder weather.

The canopy and deck fit together firmly, creating a single structural unit that requires no foundations. They represent what is essentially a piece of street furniture, which can be assembled and placed onto any existing street and sidewalk surface (and disassembled with equal ease).

Each canopy structure accommodates four full-size dining tables seating 16 to 24 people, with proper social distancing between diners. Several canopies can be placed side by side to accommodate anywhere from 50 to 70 covers, enough to ensure a profitable operation. In one of these segments, two tables are replaced with two openable kiosks outfitted with countertops, shelving, utensil and glass storage, removable trash containers, and serving supplies and equipment, which provide service stations by day and lockable storage overnight, allowing for convenient daily operation.

The canopy-and-deck structure accommodates electric heat lamps and clear windbreak panels, allowing operation of the dining pavilion to continue uninterrupted into cooler seasons. In the evening, integrated lighting fixtures throw a gentle wash of light onto the underside of the fabric canopies, reflecting a vibrant and welcoming glow on the activities beneath.

As the diagrams on the following four slides demonstrate, the dining pavilion sits atop the street and sidewalk surface like a large piece of furniture, and—also quite like a “flat-pack,” IKEA-style piece of furniture—can be swiftly assembled from pre-fabricated components that lock together into the completed installation.

Transforming City Streets Into Green Spaces

As the coronavirus lockdown took force of major metropolises, the sounds of taxi horns hushed, the skies cleared and pollution lifted. There were reports of city dwellers waking up to the sounds of nature and the song of birds, something never heard before amidst all the noise. As New York City started to peek its head out from its four-month hibernation – unlocking bodega doors, flipping open blinds, and turning around its “Open for Business” signs – there were obvious unintended positives that almost instantaneously took hold of the city that never sleeps.

As a result of unforeseen positives revealed during the pandemic, WATG conceptualized an urban planning solution that shapes a new vision for a greener New York City. The concept, Green Block, was an internal innovation competition focused on how its team of leading urban planners, landscape architects and designers could use their skills, and lessons learned from the pandemic, to transform urban spaces in a post-pandemic world for the better. Green Block allows for a green, carless, alfresco-hopping, streetscape vision for New York’s streets.

Focusing on the intersection of Manhattan’s Flatiron Building, an iconic symbol for the city itself, Green Block claws back space from the roads and reclaims it for the people and environment. Green Block is built using a modular program that transforms city streets into green spaces using a kit-of-parts system that is maintenance-free and created from 100% recyclable materials. Green Block not only adds greenery to existing cafes and shop fronts but it creates untapped revenue opportunities for retail, commerce, and restaurants, and helps clean and filter city air while beautifying streetscapes.

Green Block brings limitless value to cities and destinations – serving as a living, breathing solution to air filtration; reducing car noise, impact and pollution; providing homes for the world’s decreasing bee population; and increasing the amount of space for people to exercise and leisure. The solution provides greater opportunity for cyclists and walkers, replacing paved footpaths with lush plants; and increasing street appeal for restaurants and retail – providing untapped opportunities for outdoor dining and shopping. Restaurant operators can also use the new outdoor space to grow vegetables, herbs or fruits to serve on their menus.

New Yorkers should not forget what a cleaner city looks like, and we should all strive to find a way to adopt new ways of living that contributes to a healthier and more sustainable way of life. Our cities have long been overdue for transformation. As some flee for greener landscapes in the wake of COVID-19, Green Block proves that you don’t need to sacrifice one for the other – you can, in fact, have both the urban and the green lifestyle.

WATG is a global multidisciplinary design firm specializing in hospitality, entertainment, gaming and urban design. Founded in the wake of WWII in Honolulu 75 years ago, the firm remains independent and employee-owned to this day—pioneering, collaborative and with a profound respect for heritage. WATG’s five studios—Strategy, Planning, Architecture, Landscape, and Wimberly Interiors—stay true to their values, designing spaces that respect and enhance the natural magic of their surroundings, while delivering long-term value for clients and communities.

A Blueprint for Shared Summer Streets in Hudson

Cities across the world are working in real time to grapple with COVID-19 and its threat to public safety and devastating economic impacts. To meet our immediate health needs and to chart a safe course to allow businesses, institutions, and services to re-open, cities are innovating and adapting.

Cities big and small are rapidly changing their streets, sometimes over the course of several days, to help their residents stay safe in a time of crisis and to prepare people and societies for the health, social, and economic recovery ahead.

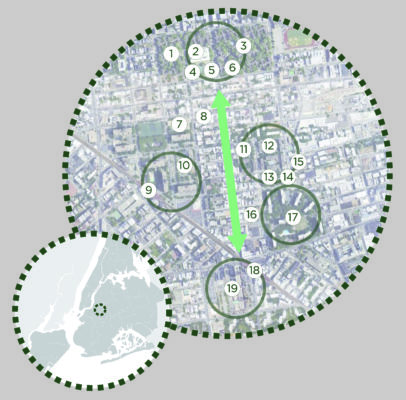

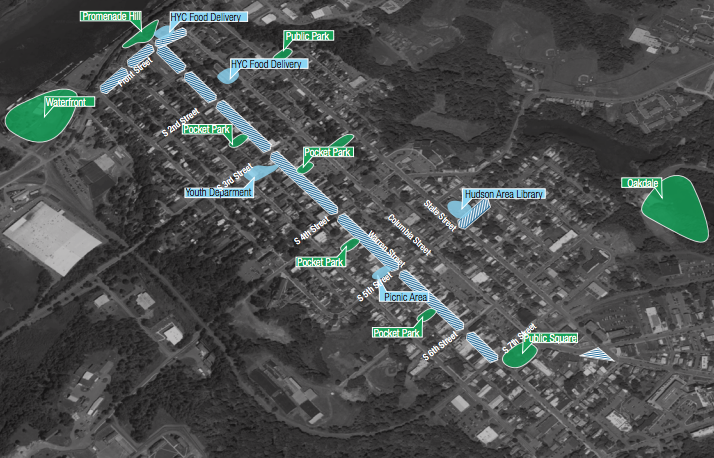

This Blueprint for Shared Summer Streets for Hudson, New York helps the City of Hudson to do just that: Shifting how space is allocated or shared and rethinking which uses are prioritized during the Summer of 2020 to help the city recover and residents to reconnect with each other after weeks of staying at home.

It also presents an unprecedented opportunity to initiate conversation about longer term change by expanding the concept of public input from a public hearing to a lived experiment, where residents can vote with their feet quite literally and the city can evaluate potential long-term changes and their impact on city health and residents well-being.

Finally, while tailored specifically to Hudson and developed with Hudson residents, businesses, and city officials it serves as a blueprint for re-opening “Main Street” in many towns and villages across New York State and the country to reallocate street space for the health and safety of its residents.

Background

Hudson, New York is a small city 120 miles north of New York Harbor on the Hudson River. Chartered as a city in 1785 and growing rapidly in the early 19th century, its economy was originally dependent on its port. Today, a growing portion of its 6,700 residents rely on income from tourism, second homes and weekend visitors to the city and surrounding region.

Warren Street, its main street, is home to over 300 small businesses and cultural organizations that serve residents and visitors. The Shared Summer Streets program in Hudson strives to expand and enhance public space for all Hudson residents, businesses and community organizations to safely reopen and re-connect with each other.

Many of the businesses along Warren Street have small footprints. Safety concerns by customers, as well as State regulations, will severely limit their ability to do business indoors.

In addition, research increasingly shows that the commonly accepted rule of maintaining six feet of distance does not apply to indoor environments where factors such as the airflow of the air conditioner and the prolonged time people might spend for work or meal in a restaurant may contribute to transmission of COVID-19. A recent survey of customers emphasizes the need to do business outdoors.

Design Strategies

Occupy Public Space

Businesses can occupy sidewalks and contiguous on-street parking spaces. The city has adapted an existing permitting process (the “dumpster permit”), to allow businesses and organizations to expand their operations into public space. Businesses or organizations wishing to expand, can do so by applying to the City of Hudson Police Department. Applications will be available throughout the program, and application site plans may be amended.

Permitted businesses will be responsible for these areas 24/7 for the duration of the program as defined by the executive order. To offset the lost revenue from metered parking, the city is contemplating a weekly fee of $24 -the cost of paying the meter for one week for such permit.

This includes maintaining waste receptacles on their property and directing patrons to use them, and for securing all tables, chairs, umbrellas and any other equipment used in the parking or sidewalk areas.

Share Public Space

To increase safety, and add more space for pedestrians to maintain distancing requirements, parts of Warren Street and Front Street will become “Shared Streets” from Friday to Sunday, 10am to sunset. Traffic will be limited to local traffic at 5mph and barriers at every intersection will slow vehicles. Drivers will still be able to drive to any address on these streets and will share the road with pedestrians. Emergency vehicles as well as public transportation will be allowed through at all times.

Businesses can occupy a portion of the sidewalk as well as on-street parking spaces in front of their business. On weekends, vehicles will share the street with pedestrians to allow for more room for distancing.

In its initial phase, these barriers are simple wooden barricades with laminated signs. Residents will be able to access their blocks during the week as normal, and normal parking rules will apply. Businesses and community groups with permits for parking spaces will also occupy those spaces on these days.

Activate Public Space

Public parks along Warren and Front Streets will be activated as public seating areas and furnished with restrooms and hand sanitizing stations. In order to ensure equitable access to Shared Summer Streets, these areas will provide amenities to those who might not be able to afford a sit-down meal in a restaurant or who feel more comfortable with picking up takeout orders.

These public areas also provide public restrooms and hand sanitizing stations, as businesses will have to limit the number of people indoors and cannot offer these facilities to the general public.

This guide was developed by Hudson Hall, Future Hudson and the Design For Six Feet Initiative. Funding was provided by the Columbia County Economic Development Corporation and The Spark of Hudson. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. We are happy for you to use, share, or remix it. We just ask you to give credit to Design For Six Feet (@designforsixfeet). The people used in our images were made by cutoutmix under the same license.

Check out Design For Six Feet’s Newburgh: Design For Play ideas competition. They received 70 submitted proposals for how to transform Newburgh’s streets; so that children, young and old, can safely play, learn, socialize and have fun this summer, and beyond. Ideas ranged in scale, from individual play elements to systems that would transform entire blocks. To read the winning proposals and learn more about the initiative, click here.

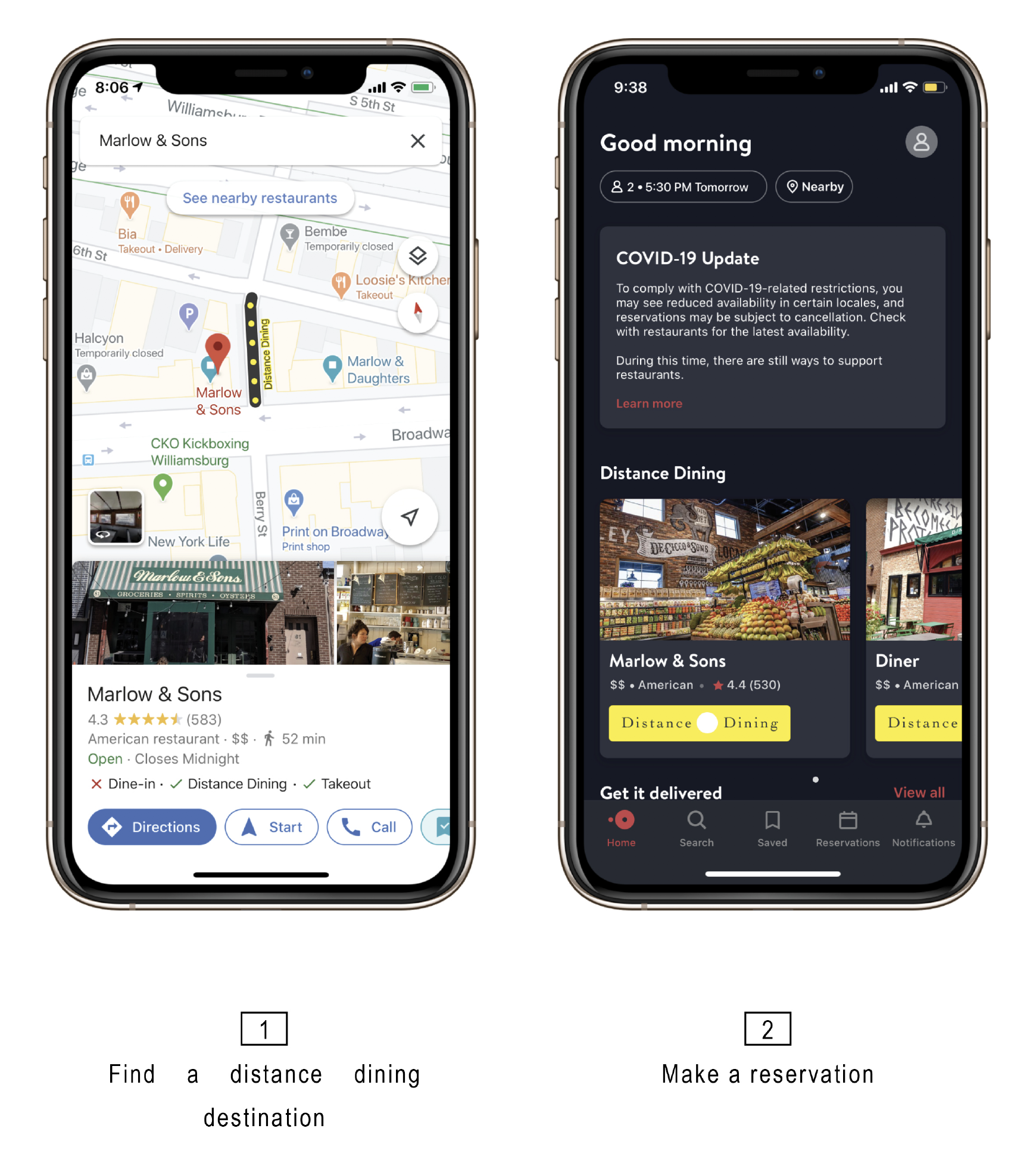

Distance Dining: A Reopening Toolkit

Distance Dining was developed and submitted to the Urban Design Forum in May of 2020, eight weeks into the Coronavirus Pandemic. The ambition was to create an equitably distributed architectural and digital toolkit that both built and signaled a safe city-approved outdoor dining experience for New Yorkers. At the time of submission, no plans were issued by the city on how restaurants could safely re-open.

On June 22 New York City entered Phase 2 of reopening which allowed outdoor dining on sidewalks, roadways, and where available open-street seating through the city’s freshly minted Open Restaurants program. Restaurants that had not completely shuttered with little notice, were faced with an ‘adapt or die’ scenario as they worked to figure seating, tables, spacing, disinfection, plastic barrier, and traffic protections – all while making their outdoor arrangements appealing enough to attract diners and assure safety.

The Distance Dining team is thrilled to see many of the ideas we imagined working well throughout our neighborhoods; bringing vitality back to the streets and supporting a portion of the estimated 80,000 jobs created by New York’s restaurants. With the Open Restaurants program a success, there is now the added promise that the city will permanently allow restaurants to continue the use of curbside space for outdoor warm-weather dining.

It is our hope then that the Mayor’s office will work not only to continue to provide the economic opportunity outdoor dining provides but will execute plans and partnerships that can ensure equitable access to the material resources required for restaurants to survive amidst a pandemic that is far from over.

Current private partnerships providing these amenities – favor the few. With Open Restaurants impact benefiting only 9,000 of New York’s last counted 26,000 restaurants, extending the program to provide warm-weather resources and cold-weather solutions beyond guidelines and open-street allowances will be critical to preserving the cultural and economic cornerstone that are New York City’s restaurants.

Summary

The Coronavirus pandemic has upended urban life. As this is being written there are yet no formal guidelines developed for the safe reopening of the restaurants who are the heart of our city. With the solutions for long-term viability remaining to be seen, it’s all hands on deck to safely help facilitate an early first step towards recovery for New York City’s restaurants.

Outdoor street dining as a form of economic and social recovery has selectively begun in Europe with early studies now starting to emerge across U.S. cities. We look to work together and learn from the wider national and global restaurant community while customizing a solution for the specific and indistinguishable needs of New York City.

Clear visual graphic markers as part of the new normal will ensure proper seating distance clarity for restaurant hosts as well as the elimination of any grey area for patrons and fellow diners.

Forecast

This forecast predicts the methods required to expedite an architectural and digital toolkit that both builds and signals a safe city-approved summer outdoor dining experience for New Yorkers.

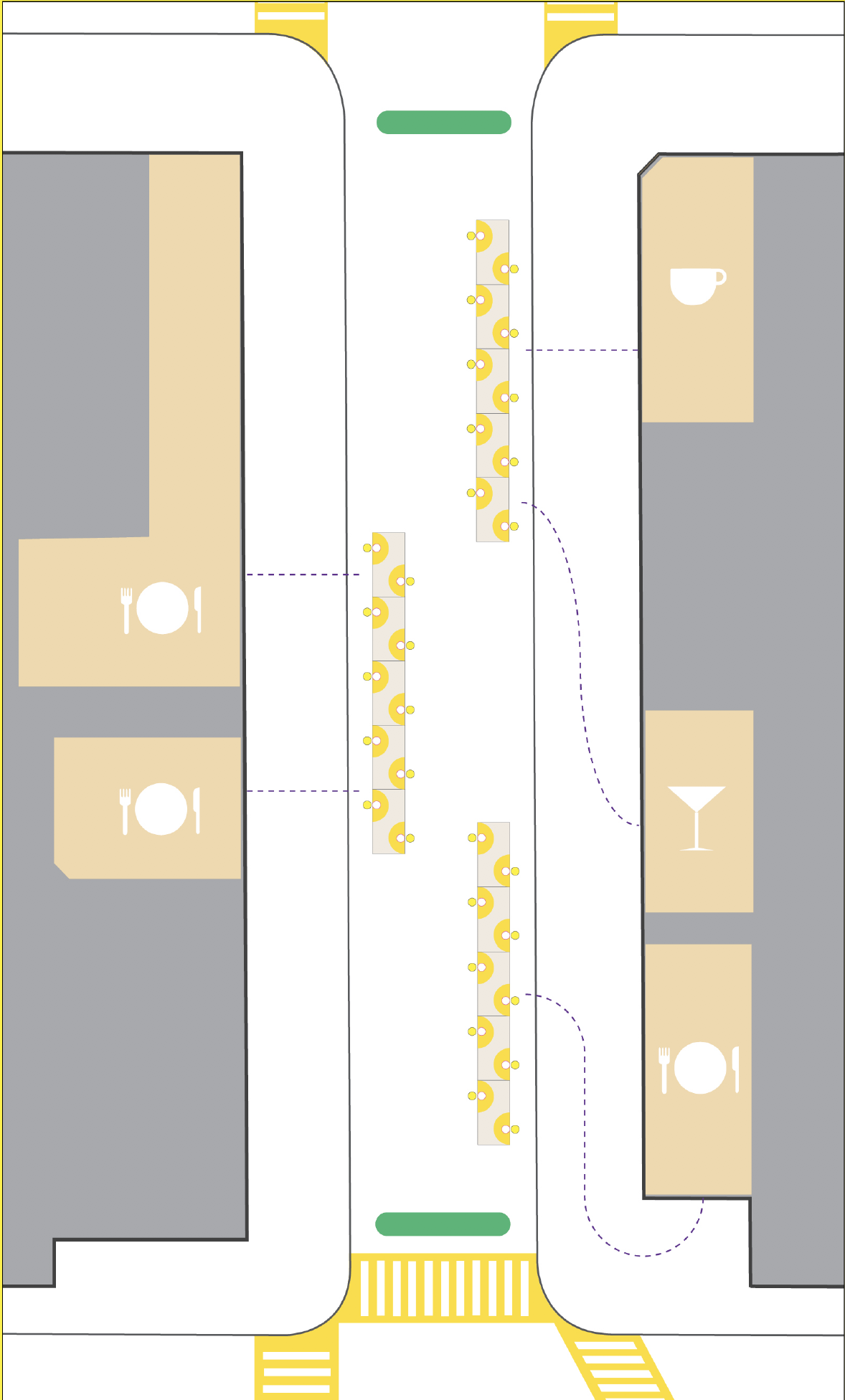

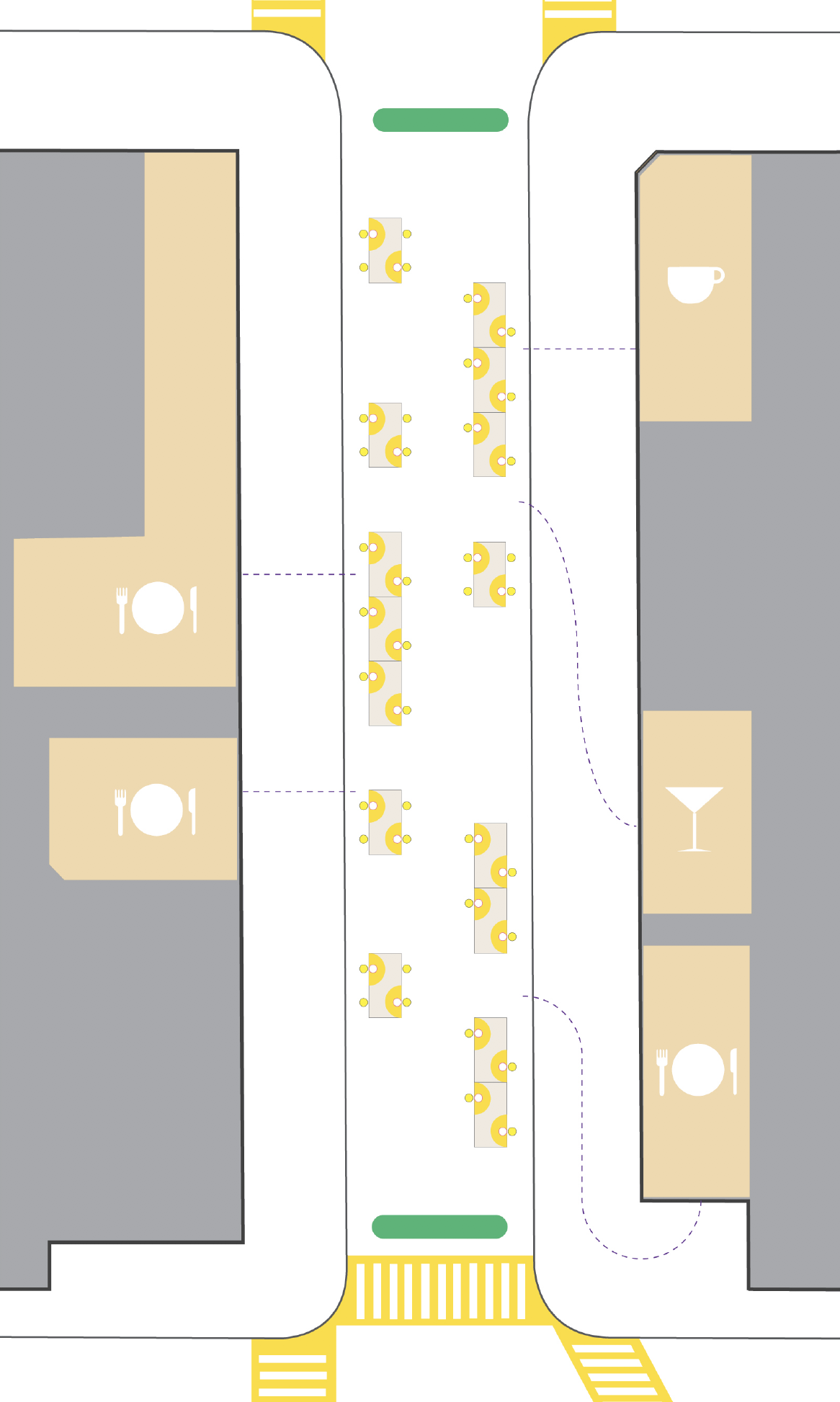

Together we imagine what it would look like for New York City to close selected streets during the summer and put those block’s restaurants outside. Transforming whole streets-into extended and protected cafe seating.

Together we imagine what it would look like for New York City to close selected streets during the summer and put those block’s restaurants outside. Transforming whole streets-into extended and protected cafe seating.

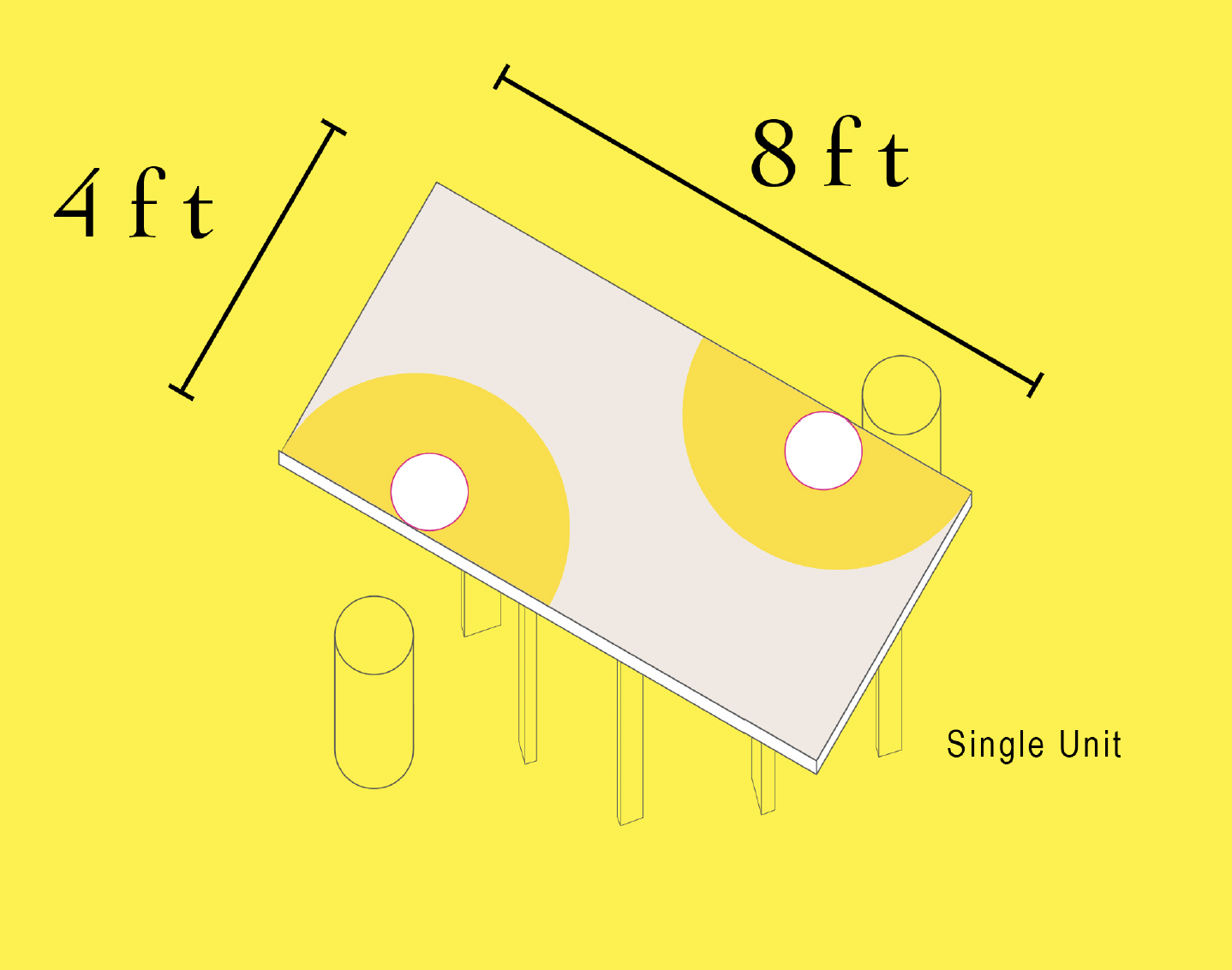

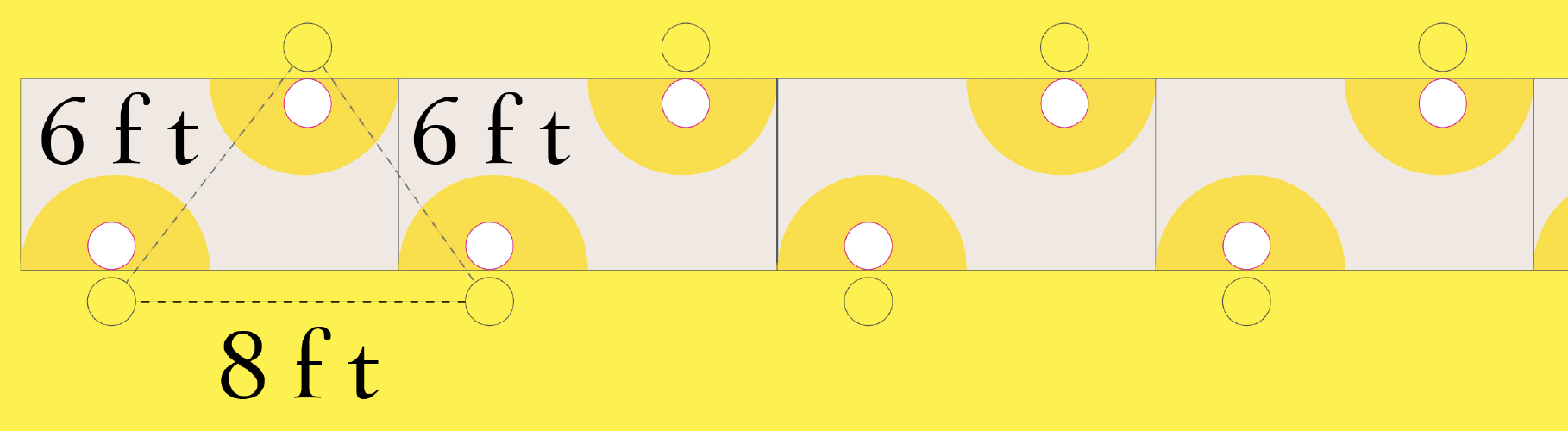

Combined units for a distanced communal table

Sample Blocks

Sample Blocks

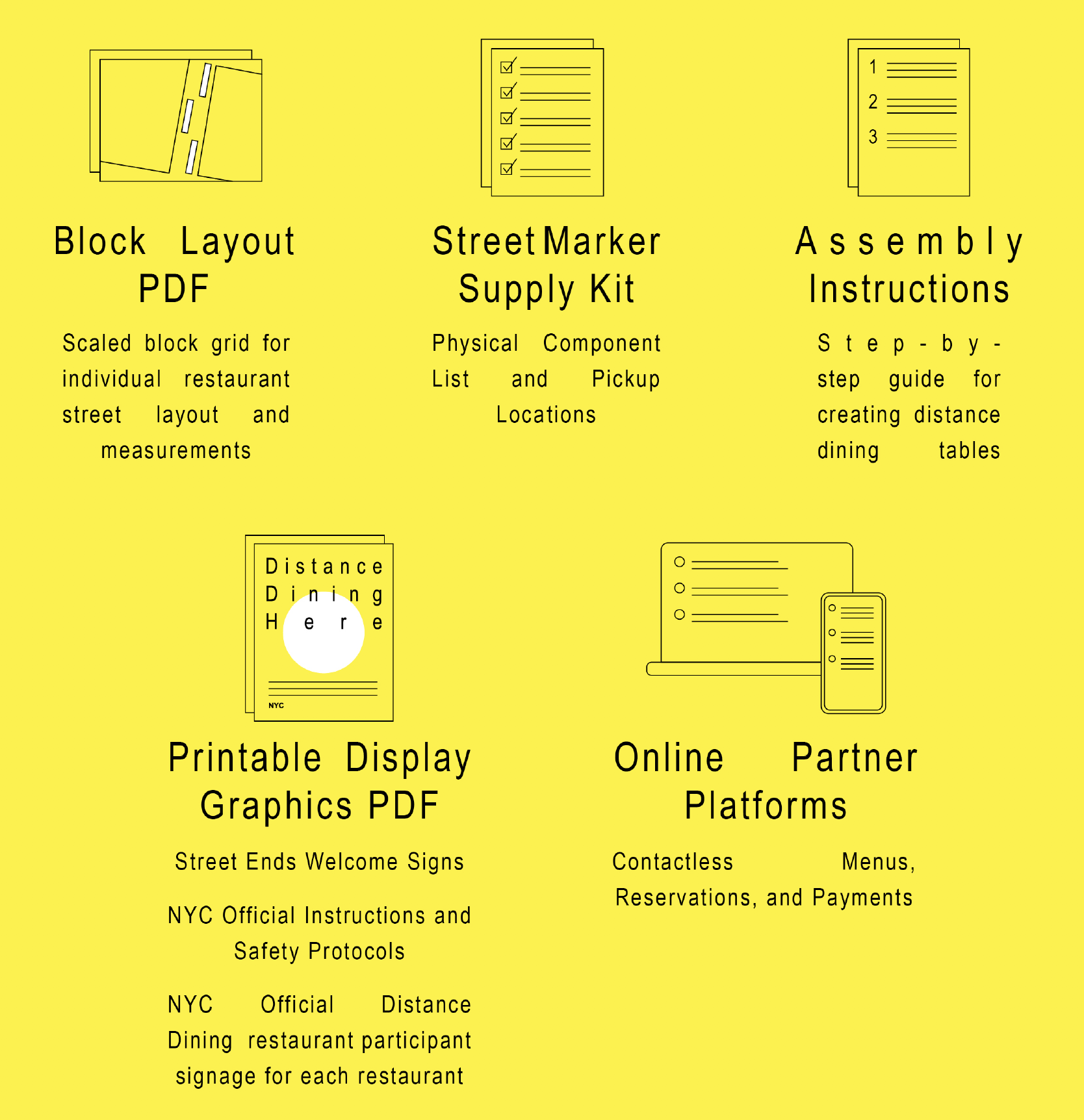

Toolkit

Maintain Social Distances: Install well designed and inviting visual and physical markers.

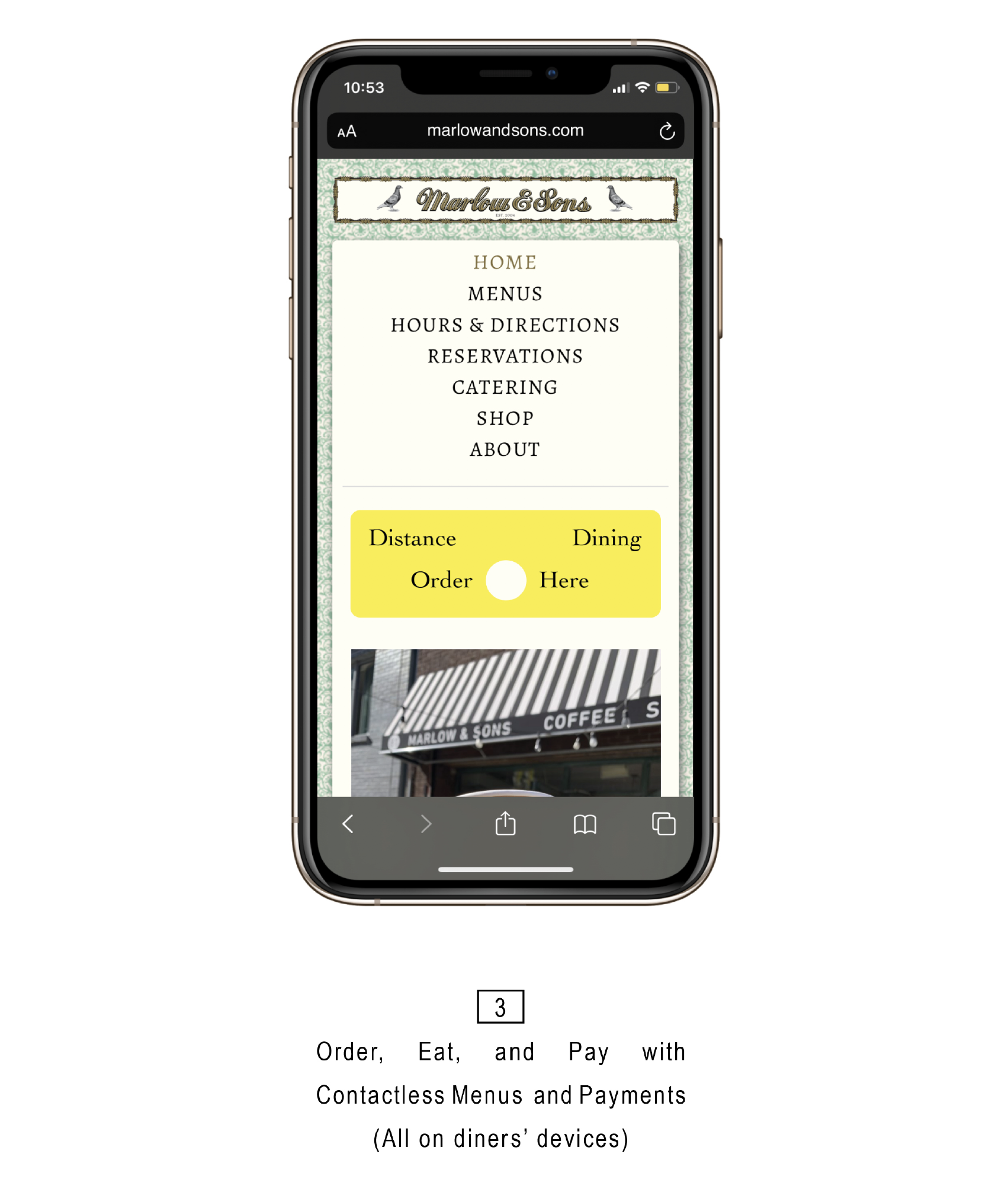

Reduce Contact Points: Provide contactless menus, reservations, and payments via patron’s cell phones.

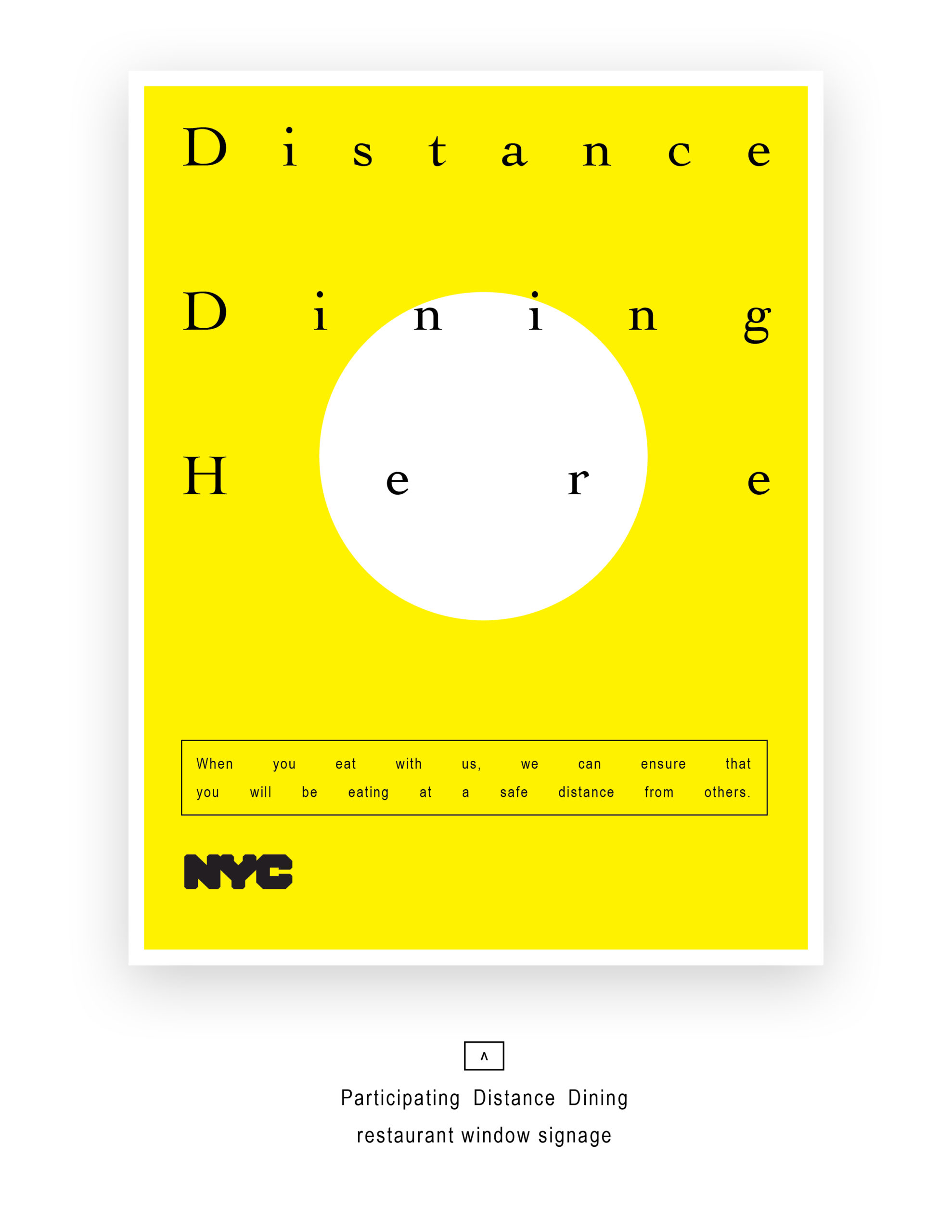

Socialize Safety: Generate a public campaign around safe Distance Dining locations and protocols.

The Distance Dining Toolkit offers the City’s restaurants the means to quickly mobilize elected individual blocks by providing a city-sanctioned downloadable guide and instructions. With templates for clear table spacing, service paths, pedestrian entry and egress, and safety protocols established in direct collaboration with the city and its health agencies, the toolkit not only empowers restaurants, but helps to educate the public on distance dining.

The use of uniform reusable materials eliminates any barriers to entry for participants. Built using only NYPD Crowd Barriers, architect/city provided plywood table templates, and restaurants own chairs, streets can be readied in a matter of hours.

Through a clear and conformed rollout, we exponentially increase not only patron acceptance of outdoor dining, but the safety and success for every participating restaurant and worker.

DISCLAIMER: All work would be done in direct coordination with the appropriate NYC and NYS Health Agencies and Task Forces. All work would require agency and task force review and approval. The Toolkit merely provides our collaborative’s ideas and designs as a means to support the city’s anticipated efforts to safely reopen.

WORKac creates architecture, landscape and master-planning concepts. WORKac is committed to sustainability and go beyond its technical requirements, striving to develop intelligent and shared infrastructures, and a more careful integration between architecture, landscape and ecological systems.

Graphic Design by Partner & Partners

Integrating Social Distancing into Street Planning

Over past several years, the Financial District Neighborhood Association (FDNA) and Buro Happold have worked in conjunction with industry experts and key stakeholders from New York City to reimagine Lower Manhattan’s street network to be more people friendly. In 2019, Make Way for Lower Manhattan, an innovative shared-streets plan for the Financial District, proposed steps to address the challenges associated with high volumes of pedestrian activity in areas with limited space. The vision plan sets forth a series of strategies that can be used to decongest areas in FiDi and throughout the city, allowing for safer, cleaner, and more enjoyable streetscape.

As New York City continues many months in quarantine, temporary measures to quell the spread of COVID-19 are now becoming realities the public will be forced to adopt for the foreseeable future. New York City, in particular, is grappling with changes to its fundamental character: density. Despite waves of escapees to homes outside the city, millions of New Yorkers will be navigating an entirely new urban landscape for months, perhaps years, to come. While the subway and above-ground street grid are relieved from their usual high volumes of traffic, the opportunity for a new approach to pedestrian and public space is becoming increasingly apparent in a new era of social distancing.

FDNA and Buro Happold are all too familiar with the challenges associated with dense pedestrian spaces. Make Way for Lower Manhattan laid out a number of interventions that, although not originally intended to aid social distancing efforts, may offer solutions to some of the challenges associated with personal space in the public realm due to COVID-19. One tool for this is concept of “shared streets”, which has been implemented successfully in places like Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Bonn.

Pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles share the street at all times, forcing vehicles to be extra cautious as they move. The increased pedestrian space can offer stress relief across areas with narrow sidewalks, which pose significant hurdles to social distancing efforts. Additionally, shared streets will better the streets year round. Priority paths like a tourist route in Lower Manhattan can encourage safe movement throughout the district; and improved services like scaffolding, vendor, and waste collection will reduce obstacles in streetscape that make people walk closer together.

Precedents from other cities in the process of reintegrating into life after lockdown suggests that public space will be in high demand. In cities across the world, storefronts are reopening and serving customers at their doorstep rather than allowing them to come inside. Public officials are recognizing this changing landscape. Recently, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer asserted that pedestrianized plazas created through street closures could be monitored to ensure utilization of appropriate social distancing measures by the public, rather than by law enforcement officials.

Her call for self-monitoring throughout the reintegration process reinforces the public’s responsibility in the reopening process. In response to this need, NYC Mayor Bill De Blasio and Speaker Corey Johnson announced plans to implement up to 100 miles of safe streets. Tools like Sidewalk Widths NYC, a tool developed by urban planner Meli Harvey that maps sidewalk widths throughout the five boroughs, can help to pinpoint areas where social distancing for pedestrians becomes challenging.

In recent months since the onset of the pandemic, Lower Manhattan has seen significant adaptations to move towards a more people-friendly public realm:

- Partnership between DOT and Downtown Alliance for a closed street on Pearl Street from State to Cedar Streets as part of the NYC Open Streets program for Covid-19 social distancing.

- DOT and the Community Board are beginning a Re-Imagining of Bowling Green to enhance pedestrian and bike experience

- The City Council and Van Alen Institute has initiative a design competition to reimagine the pedestrian access leading onto the Brooklyn Bridge

- The Black Lives Matter street mural on Centre Street demonstrates the cultural value of our streets.

Until the threat of COVID-19 is greatly reduced, New Yorkers will be living in a new paradigm. For the time being, the city’s hustle-and-bustle will likely be replaced with a slow-moving alternative – one where walking and biking take the place of a crowded subway, and proximity reigns king. The shift toward outdoor plazas and shared streets will likely spark new demands for site-assessment tools, place making strategies, visitation models, and frameworks outlined in Make Way for Lower Manhattan. FDNA can serve as an example for other neighborhood organizations that wish to make their streets as safe and habitable as possible in the midst of society’s recovery from COVID-19.

Additional team members:

Paul J Proulx, Board Member, Financial District Neighborhood Association; Partner, Carter Ledyard & Milburn

Michael King, Traffic Calmer; former Principal, Buro Happold

Alice Shay, Associate, Buro Happold

Sabina Uffer, Projektleiterin, RZU; former Head of Research, Buro Happold

Chris Rhie, Associate Principal, Buro Happold

Claire Weisz, Principal in Charge, WXY architecture + urban design

Jacob Dugopolski, Senior Associate, Buro Happold

Lucy Musgrave, Founding Director, Publica

Hugh O’Neill, President, Appleseed

Michael Flynn, Principal, Sam Schwartz

The Financial District Neighborhood Association (FDNA) has undertaken the Make Way for Lower Manhattan effort in partnership with a team from BuroHappold Engineering, supported by Massengale & Co LLC, WXY architecture + urban design, Publica, Appleseed, and Sam Schwartz Engineering. Funding for the effort was provided by the J.M. Kaplan Fund in cooperation with Transit Center and Carmel Partners.

Read the full Make Way for Lower Manhattan Report here

Exploring the Role of Parks as Community Recovery & Resilience

New York City has faced two distinct crises in less than a decade where parks have played a central role in community recovery. In October 2012, Superstorm Sandy roiled through New York City, and now we are living through a crisis of a different form with the COVID-19 pandemic. The impact on New York City in both cases were results of larger global crises. In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, a symptom of global climate change, our city waterfront communities were devastated and lives were tragically lost. As a result of the global spread of COVID-19, another disaster not contained by borders, communities all across our city are facing tragic loss and economic instability.

While different, these two events share similarities as we think about the role parks and open spaces play in recovery. Parks and open spaces are public amenities that serve as a backyard and infrastructure for all New Yorkers regardless of race, socio-economic status or any other factor. They are the site of summer vacation plans for many, especially low-income residents. They are accessible spaces for activities like sports, engaging with public art, birding, picnicking, swimming, running and walking. Our parks provide both resilience from climate change and a positive impact on mental health providing community resilience. While many needs have emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic, one thing is clear, as it was after Superstorm Sandy — our parks and open spaces are needed more than ever.

While there were many imminent needs facing the city after Superstorm Sandy that ranged from housing to food insecurity to support for small businesses impacted by the storm, similar to needs emerging now, there was a recognition that New Yorkers would need to safely access parks and beaches. In the wake of such devastation, the task took the coordination of multiple agencies, community input, and an unprecedented sequence of planning, design, and construction all occurring in under a year.

Under the leadership of the Mayor’s Office and NYC Parks Commissioner Veronica M. White, resilient comfort and lifeguard stations were placed on beaches and elevated above the flood plain, trees and debris removed, sand replenishment coordination with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was underway; and in the summer of 2013, just seven months after Superstorm Sandy devastated shoreline communities, beaches from Rockaway to Coney Island to Staten Island’s Midland Beach had record attendance. This was not just a symbol of community resilience, but a true embodiment.

Much like the coordinated effort to bring back our parks after Sandy, the city must simultaneously incorporate creative and safe ways for the public to access all parks and beaches in a socially distant manner. The COVID-19 pandemic presents a different reality whereby climate resilient building does not make parks and open spaces safe to visit as usual. However, both climate resilience and mitigating public health risks presented by COVID-19 while allowing New Yorkers to access open space are equally important. The design community can play a key role in providing necessary planning options, guidance and creativity.

A recent example in Domino Park in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where large socially distant circles were painted on the lawn that park goers used to maintain a safe space from each other, proved to be a concept that was both effective and creative. Much like the design community reimagined lifeguard stations along city beaches and a new boardwalk in the wake of Superstorm Sandy, designers are uniquely positioned to innovate other creative interventions and enhancements that encourage use of parks safely while limiting the risk of spread of this deadly virus. In collaboration with public health and park officials, and community residents, urban designers and landscape architects should be at the table to provide their expertise and help develop amenable solutions.

Social distancing circles in Domino Park in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Photo by Noam Galai/Getty Images

In addition to reimagining physical spaces, the impact of COVID-19 requires the non-profit organizations that support these spaces to think creatively about their operations going forward. As parks conservancies note, the pandemic has resulted in existing and projected gaps within New York City public-private partnerships serving our parks and open spaces. Staffing shortages due to looming government budget cuts, loss of revenue and an anticipated drop in private donations put restoration of natural areas, environmental monitoring efforts, public educational programs, park maintenance and more at risk.

As we saw in the days after Sandy, many New Yorkers have come together once again to provide support. On March 20, 2020 Bloomberg Philanthropies together with several other foundations and the New York Community Trust launched the NYC COVID-19 Response & Impact Fund; a $75 million dollar commitment to support social services and cultural organizations through a competitive grant and interest-free loan process. Additionally, the City Parks Foundation is leading a group of parks conservancies to advocate for necessary government funding and also announced the NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund, which will provide privately funded grants to park groups through a competitive process. These are great steps in alleviating the financial need for non-profit partners in the short term.

An impactful use of private or any government funds that may become available as part of a COVID-19 relief package would be to revive and expand two successful programs implemented by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation post-Superstorm Sandy. The NYC Parks Fellowship & Conservation Corps Program and Jamaica Bay Restoration Corps provided paid opportunities for recent high school and college graduates over the age of eighteen to gain experience in environmental related fields and restore impacted areas after the storm. The latter continues within Jamaica Bay parks and open spaces under the direction of the American Littoral Society, with support from the Jamaica Bay-Rockaway Parks Conservancy.

The NYC Parks Conservation Corps provided opportunities within the NYC Department of Parks & Recreation and conservancy partners for the next generation of leaders dedicated to protecting and restoring New York City’s parks. This 40-week paid program was funded by private donors and administered by the city agency. The Jamaica Bay Restoration Corps, a workforce program which initially received funding from the United States Department of Labor, assisted with much needed debris removal and wetland restoration. A new, expanded hybrid program that combines these programs and serves park conservancies citywide could both address needs of park conservancies presented by the pandemic, as well as provide employment for young New Yorkers from face limited opportunities in light of temporary funding shortages and workforce reductions.

Roles and responsibilities of fellows could range from socially distant field work to remote opportunities in research or building virtual programming, based on need and operating within local government guidelines. Through such a program, selected fellows from the New York City area would gain meaningful employment, expand their skills, and access professional development. The fellows could work with many of the landscape architects that design New York City and State park projects and the program would ensure that young people in New York City from all backgrounds can learn about potential careers in environment and urban design fields. These fellows would play a role in recovery and would be better equipped to face future global disasters as professionals.

There are certainly differences in both of these crises, but each has proven that New Yorkers can work together and creatively address methods of rebuilding while meaningfully engaging residents and our vibrant design community.

Shifting Perspectives on Street Life

During New York’s stay-at-home orders, I came to appreciate how much of my life is lived in the public realm. I sometimes yearned for a commute, albeit a short and safe one, but I also relished the neighborhood scale at which my life is now lived. I used to stop at the grocery store on the way home from the office, but now I walk or bike there from my apartment. I go outside at lunch for a quick walk. Instead of buying lunch in Midtown, I walk to my local bakery. This scale of living is one factor of many that may help us to reconsider and reimagine our streets.

An enormous percentage of public space is ceded to motor vehicles. And setting aside the many other issues that come with them – noise, waste heat, crashes, etc – this allocation of space is inefficient when buses, subways, bikes, and feet can all move more people per hour than single occupancy vehicles. During a pandemic, when the key recommendation for limiting viral spread is to physically distance oneself from others, this allocation is not only inefficient, it is unjust.

The neighborhood scale allows us to shift the way we perceive the street, not simply as a corridor for moving people as far and fast as possible, but as a space for quick and small trips via walking or biking, for recreation and exercise, and for the “third space” outside our homes and work. These uses existed before COVID, but the pandemic may allow us to see them in a new and clearer light. And this shift in perception may also allow us to see the streets in even more new ways. Flood resilience or heat island, for example, can be mitigated within the right of way. We can develop better systems for waste management or provide public drinking fountains to reduce plastic waste. And we can rethink the way we deal with deliveries – which will continue to increase – when we shift our view of the street.

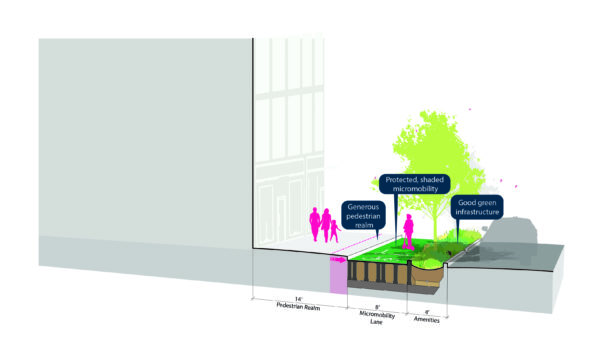

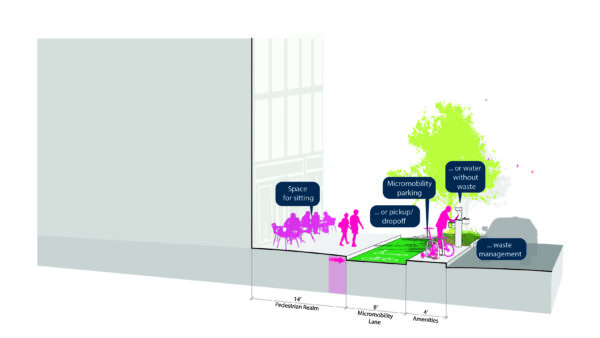

All of these moves will require us to change the way we allocate space. Our practice at Stantec has done a lot of work envisioning the way our streets could look in a pre-pandemic context. The vision is not only still relevant; it is even more urgent.

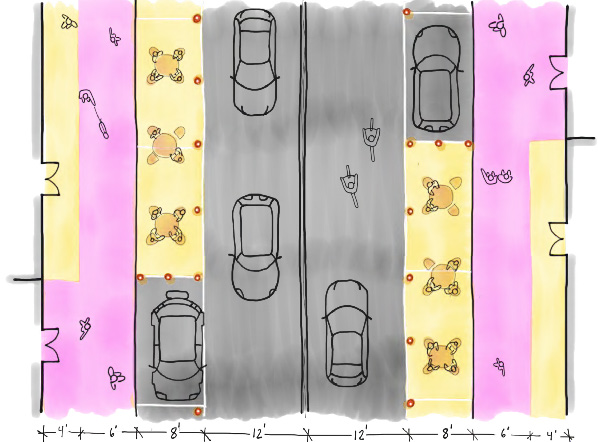

The idea is to reclaim space from vehicular storage and superfluous travel lanes to accommodate a range of other uses: wider sidewalks, protected micromobility lanes, green stormwater infrastructure and plentiful trees, and a variety of curbside amenities such as bike or scooter parking, pickup/drop off zones, and loading zones.

The diagrams show a long-term vision for the future, but we can start small through rapid implementation strategies to bring more fair and safe streets to our city now. Temporary barriers and paint can quickly reallocate space, and popup parks, planters, and other amenities could be included. Business Improvement Districts or local businesses could participate as well, allowing New Yorkers to peek into the future to more permanent solutions.

Recovery may be long, and our city is unlikely to look and feel like it did pre-COVID, but with every disruption comes great opportunity to shape our city for the better.

Communities are fundamental. Whether around the corner or across the globe, they provide a foundation, a sense of place and of belonging. Stantec cares about the communities we serve—because they’re our communities too. We’re designers, engineers, scientists, and project managers, innovating together at the intersection of community, creativity, and client relationships. Balancing these priorities results in projects that advance the quality of life in communities across the globe. Find us at stantec.com or on social media.

Inside Out: A Case Study for Improving City Streets

We believe that the urgent measures we take now to protect our community’s health should be envisioned with an eye toward improving the livability of our city once the emergency is over. We propose to select streets central to communities that are underserved by the public park system and create a series of green spaces which will serve to improve the quality of life both now and later.

While public life is impacted by the Coronavirus, the parks will create new spaces for safer, outdoor gathering and facilitate social distancing solutions for adjacent small businesses–like covered seating for restaurants or socially distanced food bank distribution. Once the emergency has abated, the parks will continue to demonstrate how strategically expanding space for pedestrians, cyclists, and parks in the city can create safer, healthier, greener neighborhoods.

We selected Graham Ave in Brooklyn between Broadway and Maujer Streets as a model street for this intervention. Serving as an economic hub for East Williamsburg, Graham links three major NYCHA developments with Woodhull Hospital and Lyons Community School to the Southern and Northern extents. NYCHA and Parks Departments green spaces are nearby but are wholly inadequate for the density of people represented in this subsection of Williamsburg. The addition of nearly 14 blocks of flexible green space would be a boon to the personal and economic health of the community while providing a link between existing public services and programs.

While the Coronavirus has wreaked havoc on our urban community, it could also unlock a new attitude toward how the city’s parks can serve a neighborhood. Instead of traveling to visit natural outdoor settings, those settings could be dispersed throughout the urban blocks, breathing new life into the grid for the long term health of our city.

What is in the Toolkit?

What is in the Toolkit?