Restricting non-manufacturing uses is essential to the success of City industrial policy.

By Armando Moritz-Chapelliquen, ANHD

–

Understanding New York City’s industrial and manufacturing sector requires a serious discussion about the various programs, policies, and priorities directed at supporting this sector as a whole. While these various initiatives may be enacted by different parts of city government, such as the Department of Small Business Services (SBS) handling funding programs for manufacturers, or the Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) running a program to support the development of affordable industrial space, the success of these individual programs is often intertwined.

In fact, the success of either of these agencies is dependent on land use policy that reflects a prioritization of zoning for jobs. In the case of SBS, existing manufacturers can not compete with more lucrative uses when it comes time to renew leases or consider expanding their business in the city. For EDC, acquiring space for manufacturing development is difficult when manufacturing zoned land can go to various non-manufacturing uses. Land use policies, or lack thereof, have enormous implications on the success of other policies in the industrial and manufacturing ecosystem. Consequently, we must prioritize an effective industrial land use policy in order to have a viable ecosystem.

Greepoint Wood Exchange. Courtesy of Jim.henderson/Wikimedia Commons.

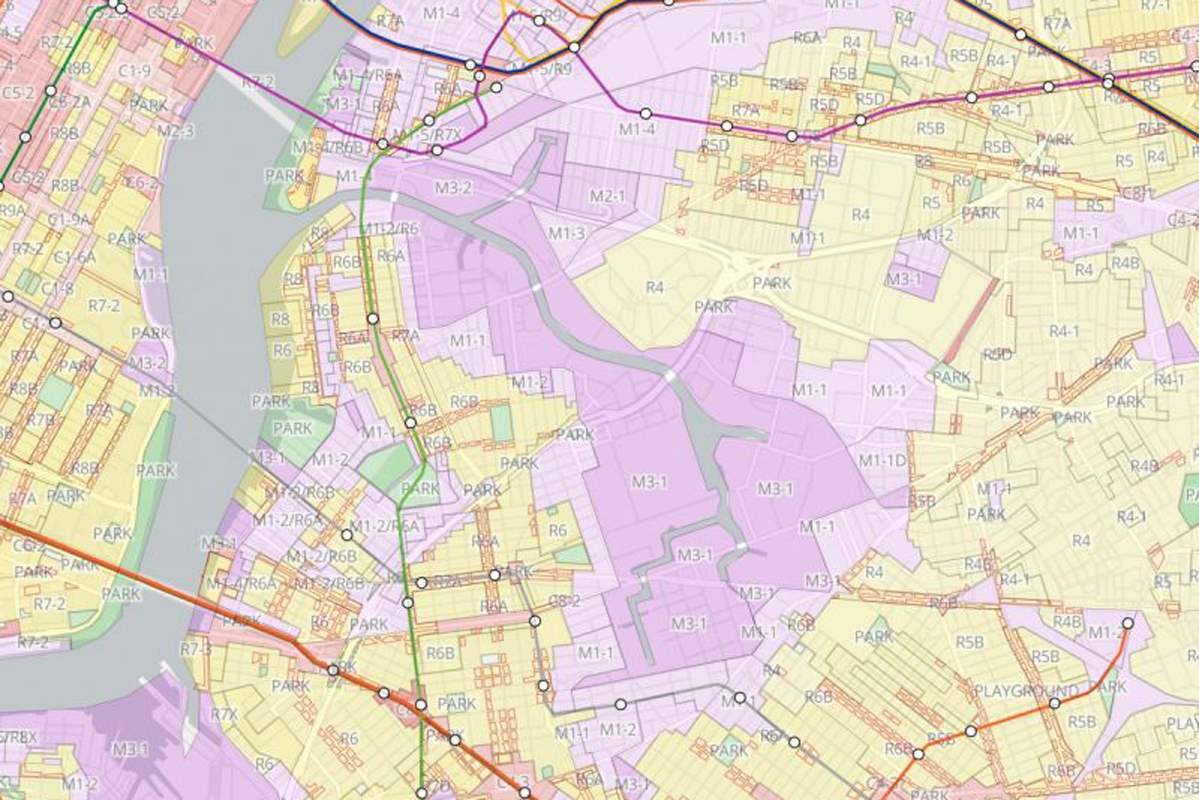

Thankfully, there is no shortage of policy recommendations, reports, and studies to inform policymakers in this regard. Whether it is the 2005 framing of the Industrial Business Zones, the typologies defined in City Council’s 2014 Engines of Opportunity report, or the subareas in the Department of City Planning’s 2018 North Brooklyn Industry and Innovation Plan, a common theme is zoning for three particular typologies: 1) Core Industrial-Only, 2) Commercial-Industrial Vertical Mixed-Use, and 3) Residential/Commercial/Industrial Vertical Mixed-Use. The common denominator to each of these typologies is use restriction.

Use group reform, the restricting of uses permitted as-of-right in our manufacturing zoning, is essential to the success of any manufacturing zoning, particularly mixed-use zoning. Current manufacturing zoning creates little, if any, new manufacturing space on its own. It is illogical to assume that mixing this admittedly broken zoning with commercial zoning (in pursuit of a cross-subsidy model) will succeed in creating new manufacturing space. Similarly, because it is already acknowledged that our current manufacturing zoning creates little, if any, new manufacturing space on its own, any mixed-use model that creates any amount of manufacturing space, no matter how little, will look better by comparison. In other words, we will settle on the tolerable rather than plan for the good.

Accomplishing use group reform requires a somewhat paradoxical approach: We should define manufacturing by what it isn’t, not by what we think it will be. This is for two simple reasons. First, technological innovation will always outpace our city’s zoning laws. Second, there are various uses, self-storage, hotels, nightclubs, big box retail, etc that are clearly not manufacturing but are permitted as-of-right. Restricting these non-manufacturing uses is an obvious first step.

These policy prescriptions are neither complicated nor revolutionary. The lack of progress on advancing these goals is not due to lack of data, but due to lack of political will.

–