The Urban Design Forum’s 2019 Forefront Fellowship, Turning the Heat, addressed ways how urban practitioners can advance climate justice principles across New York City. In partnership with the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, Fellows surveyed neighborhoods, studied buildings, interviewed local and international stakeholders, and produced creative research on mitigating heat. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on creating circular economic and sustainable models in NYC, developing community resiliency within NYCHA housing, factoring design into preventative care, and establishing a climate first approach to housing which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

Read interviews with Chloe Arnow and Tina Johnson to accompany this proposal, and view the full compilation of Turning the Heat proposals and interviews here.

by Digser Abreu, Rhonda-Lee Davis, Dorraine Duncan, Lydia Gaby, Gloria Lau, Manuela Powidayko

Context

When you look at your own neighborhood, who are your community heroes? The important work that keeps a community safe and cohesive in many New York City communities is most often done by women, often minority women, many of whom are seniors. These are the people that build the trust of the community and connections across groups. They are extremely valuable resources every day and in a crisis, especially for those around them. Yet, these community anchors have limited power over their living conditions. They and those they serve are critically vulnerable to disasters, especially in neighborhoods owned by the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), which houses the largest vulnerable population in New York City, where we focus our proposals.

As New York City confronts the realities of climate change along with billions of dollars of infrastructure needs, the resources to build social, economic, and environmental resilience are not justly distributed or available to all communities. Systemic challenges combined with the trials of everyday life make it especially difficult for vulnerable communities to prepare and adapt for climate events by depleting a community’s resilience reserve (Hernandez, et al., 2018).

Centering the voices and experiences of the most vulnerable in diverse initiatives can create long-lasting community resilience. Marginalized communities must build the autonomy to enact resilience measures that respond to short-term shocks and long-term stressors.

We must take action with community-led strategies that build long lasting resilience in centers most at risk, and we must do so with those most active in the community.

The Importance of Social Capital for Community Resilience

Community resilience describes the collective ability of a neighborhood to deal with everyday stressors and efficiently resume the rhythms of daily life following sudden shocks. Some communities are more prepared and resilient, while others bear greater burdens. In New York City, marginalized communities and communities of color are generally most vulnerable and susceptible to shocks.

For low-income residents, everyday stressors require individuals to respond and adapt frequently and quickly to maintain stability. These stressors, or social vulnerabilities, are related to socioeconomic conditions like housing, equity, and health (Flanagan et al., 2011). They present chronic impediments to an individual’s ability to survive, and make it more difficult to respond to sudden shocks.

If socioeconomic stressors are constantly eroding an individual’s capacity to respond, then when shocks occur, that capacity is severely depleted. People and communities have resilience reserves that are either being nurtured or used. In order to bolster resilience reserves before, during, and after disruptions, there should be equal focus on addressing the everyday stressors that contribute to vulnerability and on building social capital.

Social capital, or the ability of individuals to create benefits within their personal and community networks and to leverage ties to pursue desired outcomes, is key to community resilience. It is a particularly crucial indicator of communities’ ability to adapt to environmental or climate disruptions (Aldrich and Meyers, 2014). In a crisis, when everyday stressors are compounded by weak social capital, a community and its residents experience more damaging outcomes.

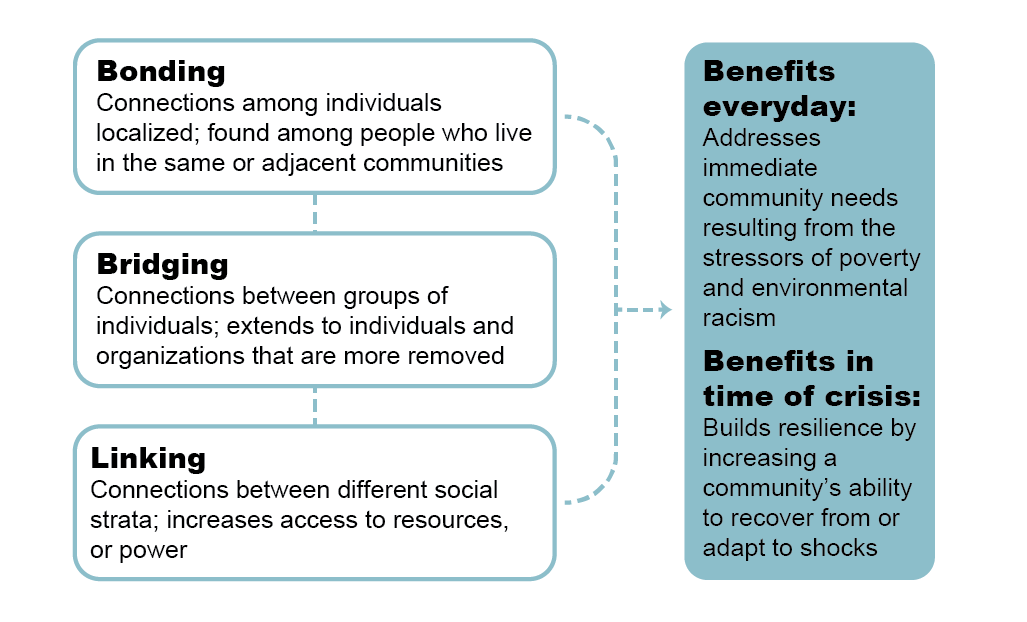

The social capital theory centers social capital as the balance of bonding, bridging, and linking capital (Woolcock,1998). Social capital provides the opportunity to reduce the stressors that vulnerable communities face while increasing the collective ability to respond to sudden shocks. We assert that low-income communities around the city have strong levels of bonding capital but often do not have the bridging and linking capital to truly transform the persistent stressors that impact the community’s quality of life and advance their long-term resilience.

We call for adapting existing strategies to increase resilience by enhancing social capital within, between, and amongst communities, so that they may serve themselves. Our work remains grounded in the everyday economic, racial, and social realities of vulnerable groups who are consistently most impacted during societal shocks.

Why NYCHA?

We focus our recommendations on NYCHA communities, which are particularly vulnerable to climate shock, but also hubs for community action. NYCHA houses approximately 4.4% of the city’s population (Gates et al., 2018), and consists of people most at risk of increasing climatic shocks. And, across all developments, about 40% of NYCHA households are headed by a person over the age of 62. Available information from NYCHA further highlights the everyday stressors of their tenants. The average household income is about $25,000. While approximately 1 in 3 individuals work, 40% still receive living or housing assistance (NYCHA, 2019). In January 2020, residents were waiting an average of 138 days for repairs in the 10 largest NYCHA developments (NYCHA, 2020). 506 individual towers across 300 developments lie within the 100-year floodplain (Hernandez, et al.,2018). For years, residents have worked to call attention to substandard living conditions within their developments.

NYCHA residents contribute to New York’s economy by holding many jobs in the workforce, creating businesses, and by contributing to various forms of social and cultural capital within the city. Yet many NYCHA residents are faced with many disparities such as poverty, illness, and a crumbling infrastructure coupled with climate change. While a myriad of programs already exists to support residents, as a whole, NYCHA residents still experience everyday stressors because of social, economic and physical vulnerabilities.

In order to build resilience within NYCHA communities, residents must be able to identify, design, and implement measures that respond to individual and community-level stressors and shocks. It is imperative they be able to chart their path towards self-determined resilience.

“How do you prepare 11,000 people for the next tragedy?” (Green City Force, 2015).

Principles

The strategies and resilience opportunities that we highlight build community resilience by strengthening social capital and addressing everyday obstacles and sudden events. The four strategies highlighted below benefit individuals and communities by enhancing adaptation efforts and reducing the stressors that deplete resilience capacities needed during times of shock.

The tenets of our work include:

- Meeting residents and stakeholders “where they are” by building on what communities already have and what is already working.

- Focusing on everyday needs and addressing systemic stressors, especially those pertaining to knowledge, funding, participation, and health.

- Working on addressing problems related to climate, justice, and equity.

Resilient Strategies and Opportunities

Community Currency

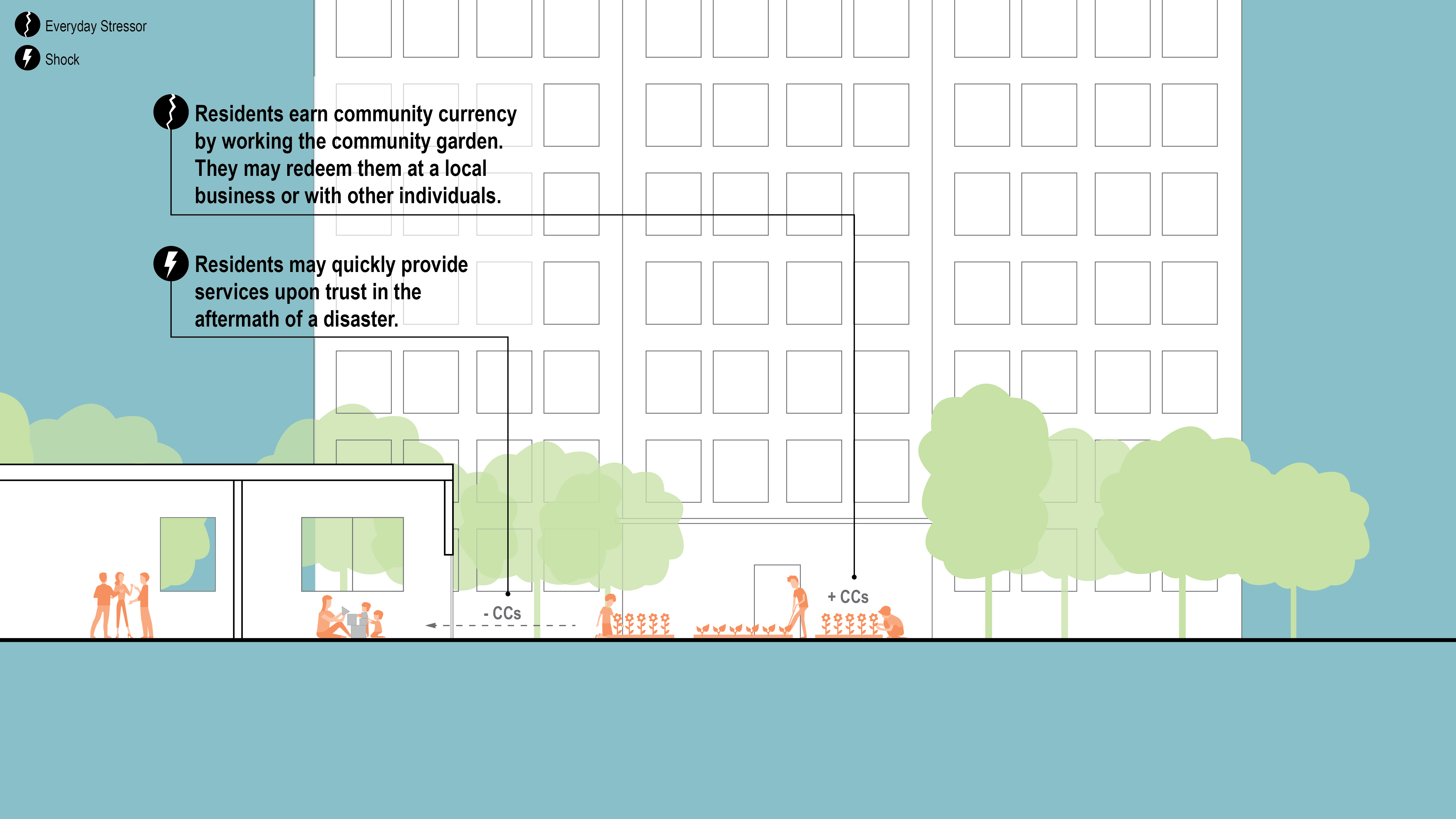

Community currency is a social exchange system, and alternative economic flow, that is established by groups, like members of a locality, or association, designed to meet their common goal(s) to pay for services that typically go unpaid. This strategy builds on the work of the nonprofit Asia Initiatives, which developed a social currency system named Social Capital Credits, (SOCCs) that helps communities in India, Kenya, Philippines and the United States (Washington DC, and most recently New York City) obtain the power of choice and become the main stakeholders in their personal and collective success. Individual needs such as senior care, child care or pet care; medication or groceries pick up; or recycling support for waste management may be bartered with credit earned from completed tasks which reflect community need (see Asia Initiatives case study).

Asia Initiatives engages communities to better identify individual and community needs and priorities. In order to support community exchange, residents will then create earning and redeeming menus that reflect these same needs and priorities. Credits are earned for performing acts of social good and then redeemed for critical resources. Community Currency keeps spending power circulating within the local community and fulfills specific community needs. It allows people to use their connections to each other, or the resources that they control (time, expertise, labor) – in exchange for another. It allows for an alternate flow of local services or goods that they need but cannot pay for within the current financial system.

“How do you leverage people’s strengths within a neighborhood?” (Geeta Mehta, Co-founder, Asia Initiatives)

Resilience Opportunity: To prepare for times of shock, and meet daily demands, communities can identify priorities through sociocratic and grassroots dialogue. Community Currency, the conversion of deeds to services, establishes an exchange system that can provide disaster response and create resilience. It would not require money, but would enhance crucial social bonds that can be leveraged during disruptions and post-shock. Communities can use Community Currency to develop more resilient connections amongst stakeholders that could be leveraged during times of need. Assistance and participation from community partners, such as small business owners, can help scale and implement a social exchange system to address challenges of limited funding. Individuals, and even businesses, may earn Community Currency through participating in resilience planning and emergency preparedness workshops and then exchange them with others locally.

Purchasing Cooperatives

Purchasing Cooperatives (co-ops) create cost savings for participants by aggregating demand across a large population of individuals to get lower prices from selected suppliers. These co-ops are proving beneficial to low-income communities who experience multiple cost burdens (rent, energy, health, food), often simultaneously. The co-op is flexible in that it is an economic process which can be applied to demand for any good or service, such as food, emergency supplies, pest control, HVAC maintenance or even weatherization (Arnow, 2020).

There is significant potential for Purchasing Co-ops to scale throughout NYCHA campuses given the success of the Farragut Food Club pilot at NYCHA Farragut Houses in Dumbo, Brooklyn (see Farragut Food Club Case Study). Aggregating demand for food using the online Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits has saved resident’s time and has the potential to save them money on groceries (Arnow, 2020).

“Before Farragut Food Club, I would get on the bus and go get groceries, totally it would take three hours. People take for granted that they are able to order groceries online.” (Denise Grant, Director of Orders. Youtube: Farragut Food Club, 2019).

“Now with the Farragut Food club, it takes me 15 minutes, 20 minutes to shop. “(Denise Grant, Director of Orders. Youtube: Farragut Food Club, 2019).

Resilience Opportunity: Food purchasing co-ops provide NYCHA residents with access to time and cost savings. Still, Co-ops are not widely distributed across communities that can benefit from them most. They can provide an additional opportunity for low-income residents to make decisions affecting long-term agreements with service and resource suppliers to ensure affordable price-quality ratios; this can also benefit public housing infrastructure as a whole by reducing costs of repairs and building systems. In order to bring about more physically and socially resilient community networks, purchasing co-ops can be expanded and scaled to buy any number of goods and services. As an example, they may be combined with weatherization projects for the implementation of conservation measures in NYCHA units that save on household energy costs. Co-ops can be used to meet community needs by procuring bulk purchases and savings on energy, transportation and food costs. Those savings can in turn be used to secure additional resilience resources and fund routine community goals.

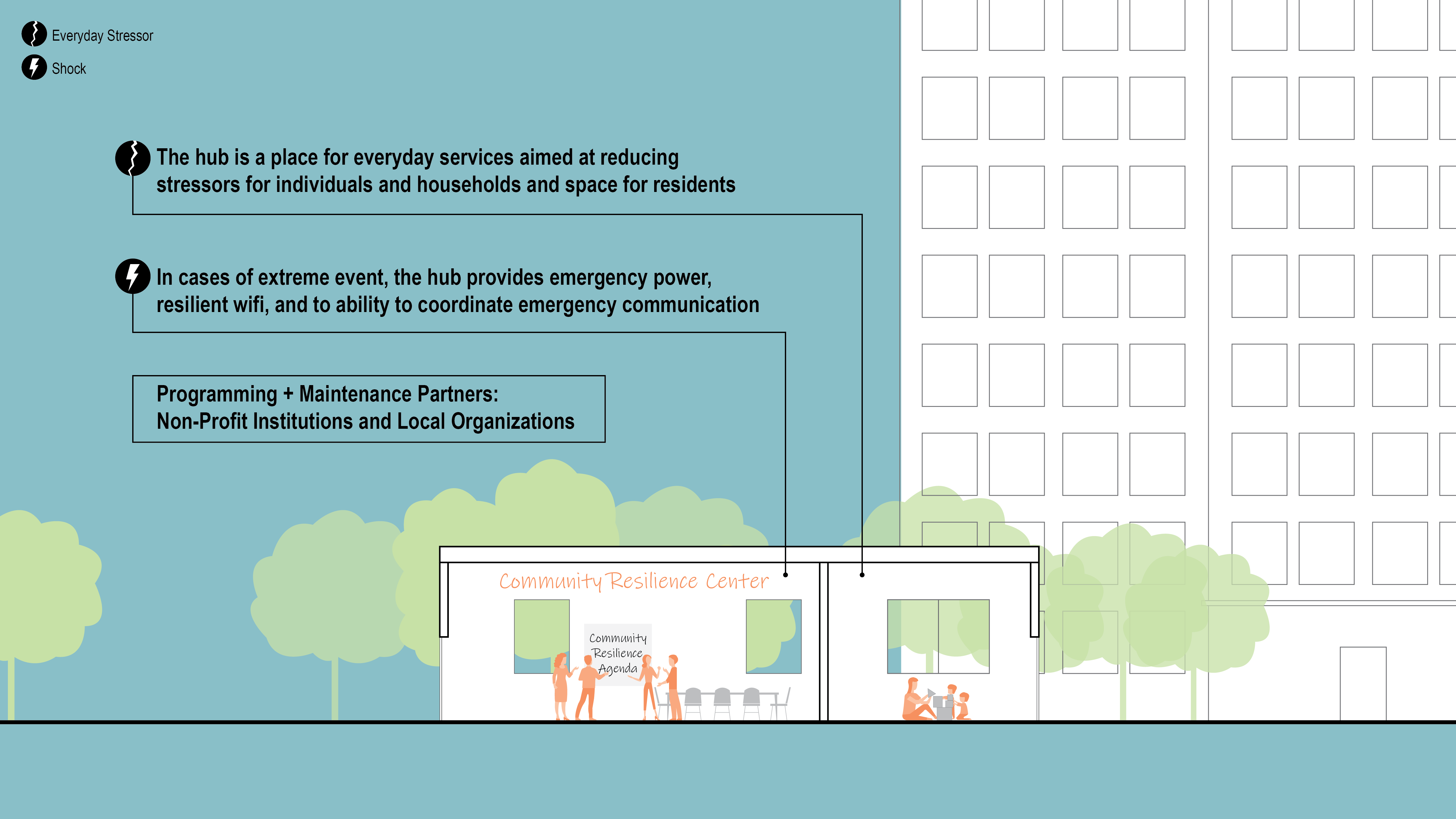

Resilience Hubs

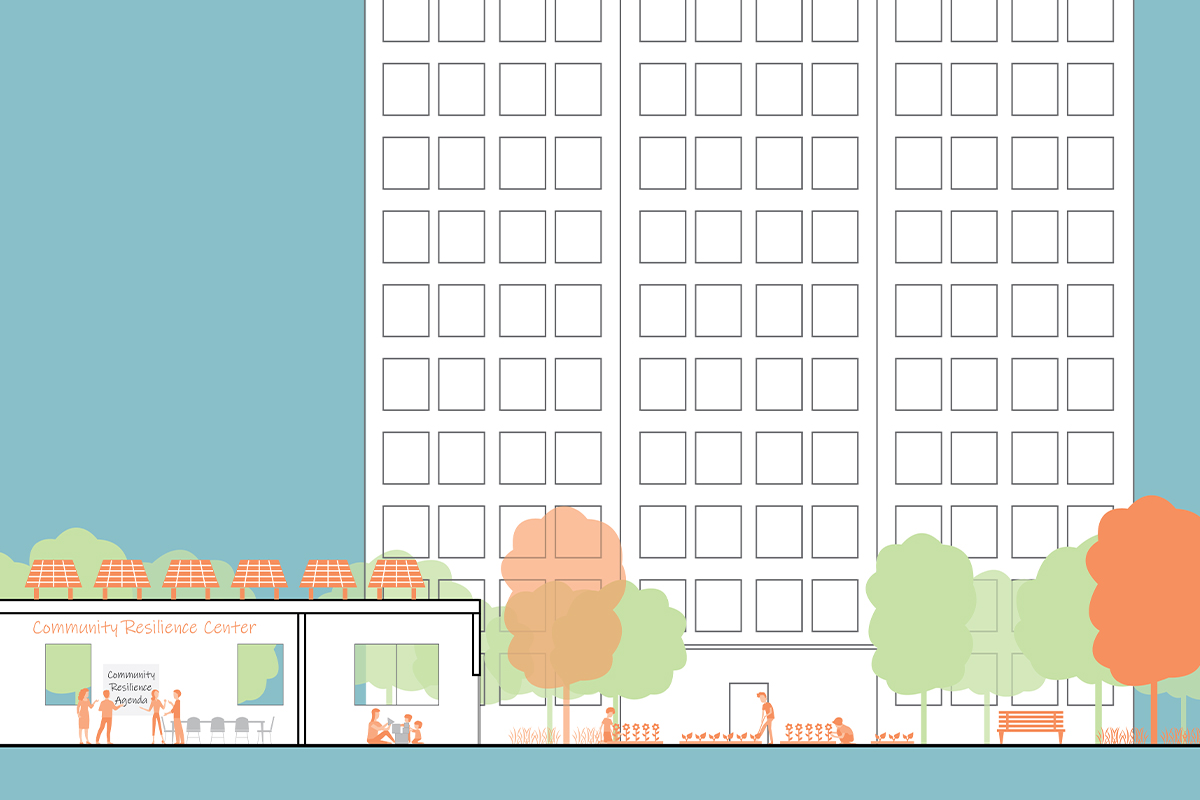

Communities in NYC and throughout the US have embraced community resilience projects in community centers and spaces to promote centralized services that address these same stressors and classify these spaces as Resilience Hubs. Community facilities can be routinely leveraged as spaces where stakeholders come together to design solutions to everyday stressors experienced by neighbors related to financial wellness, environmental health, food security, and many other vulnerabilities that were present prior, during and after the current pandemic.

While hubs come in many forms, they directly affect the levels of social capital in a community by providing a space or infrastructure that is flexible to parents, seniors, women and others actively engaged in getting people information, services, resources and creating plans. There are examples of hubs serving as both physical and virtual spaces for community information (see Red Hook Hub Case Study), resilience hubs that grew out of the collective desire of neighborhood CBOs to learn from and mitigate the effects of climate shock (see LESReady! Case Study), and those that occupy physical spaces that address stressors everyday but also provide much needed services during crisis periods (see POWER House Case Study).

“It’s important to note that someone who is coming from outside the community who wanted to do something like this would not have been able to do it. [The NYC-EJA member] used the ties they already had from other work and built off connections that they already had.” (Jalisa Gilmore, Research Analyst, NYC-EJA on community engagement)

Resilience Opportunity: NYCHA residents have access to a network of more than 400 community centers that support workforce development, education, senior care, daycare, health care, and community services (NYCHA Fact sheet 2019). When activated, these spaces enhance, support, and provide neighborhood activities and jobs by and for residents, community-based organizations, private developers and institutions on NYCHA campuses (NYCHA REES, 2020).

An opportunity exists for residents to pursue the use of underutilized community centers for resilience with their social groups. It would not only add value to NYCHA communities, but open avenues for neighboring local organizations to reach residents for resilience efforts. Existing community facilities may already provide vital services in communities, however, the community leaders who support these spaces do so without classifying their work as ‘resilience’ nor by actively classifying their spaces as Resilience Hubs. By reframing the contributions and roles of this critical space, a Resilience Hub can access funding for emergency management, community cohesion initiatives and solar installs and upgrades (see POWER House Case Study). A virtual hub of information is an important means of engagement on NYCHA campuses where there are longstanding issues with mobility and safety. If there are concerns with the ability or willingness of residents to leave their towers, virtual hubs can keep these residents connected to resources.

NYCHA community centers can operate at their full potential as Resilience Hubs and become dynamic places for everyday services which also allows people to prepare for times of shock. The space must be attractive to the public in its design and neutral space which can allow for physical distance while still allowing for social discourse and a place where people can connect. They can link residents to technical resources and services, as well as allowing communities to determine their own resilience agenda in preparation for emergency and shocks. They would be inclusive as a place to effectively interface with advocates around initiatives that positively affect their neighborhood. Resilience Hubs in the place of the contemporary community spaces, primarily in NYCHA campuses, can be localized creative spaces that allow for reactive and proactive adaptation. They can serve as sites for emergency coordination and communication which will further enhance social capital by strengthening trust across groups through collaboration on shared goals.

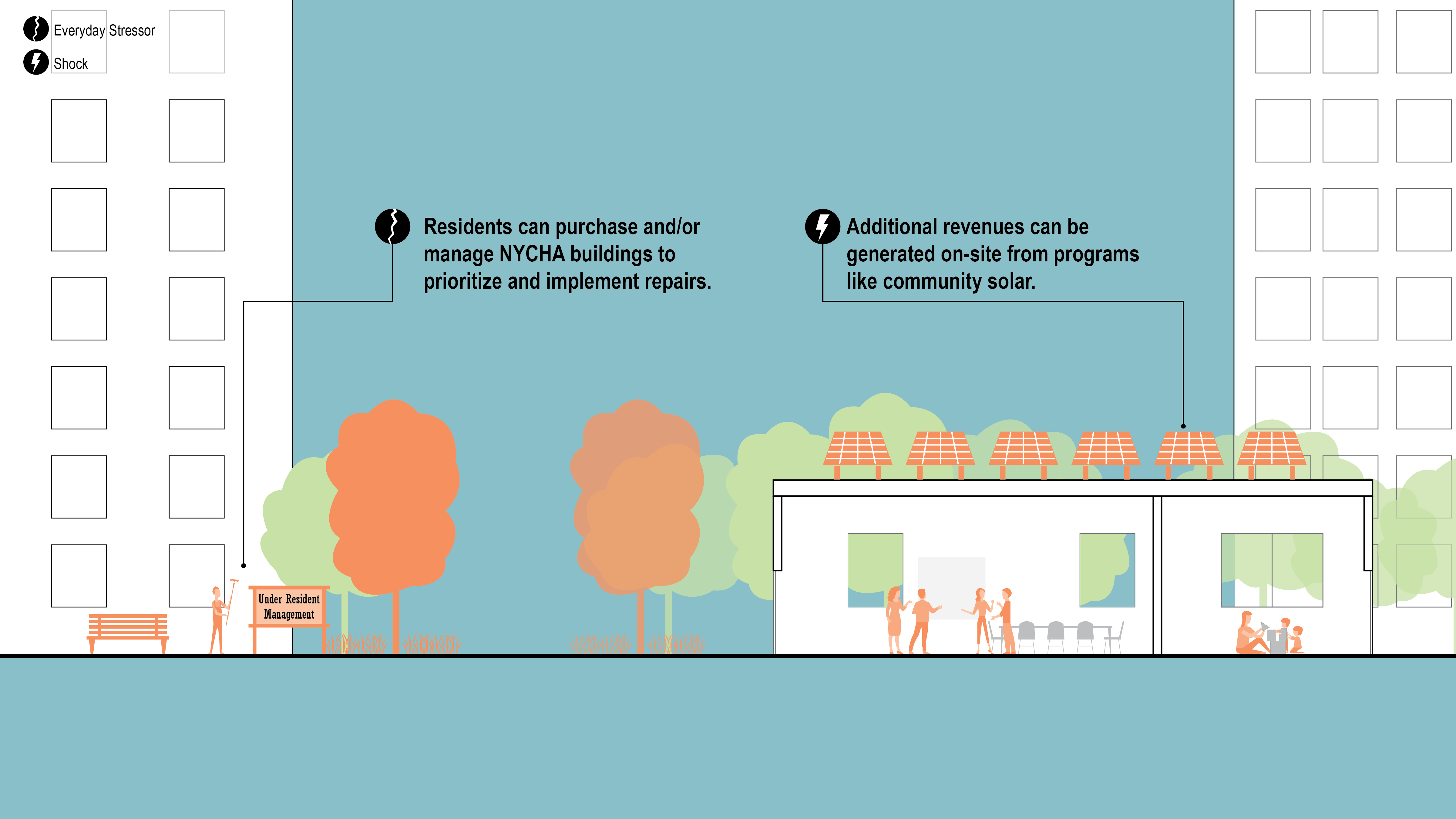

Resident Power

Resident Power is seizing opportunities to build, share and own community funding and resources. Power can be built through strategies that leverage management/ownership transfers or new investments — in infrastructure, real estate, other community assets such as solar panels, or retail sales — to provide new and potentially permanent funding for resident use. Residents can apply resources towards physical improvements to NYCHA campuses or other discretionary supports for community members.

Under NextGen NYCHA 2.0, New York City is advancing several strategies to address the poor infrastructure on NYCHA campuses. These strategies include selling the rights of air, land, and buildings on NYCHA campuses to private sector entities for construction, rehabilitation, management, and social services to address capital needs. Many residents have organized through groups like Tenants’ Associations to advocate for new public facilities, advances on capital improvements, and improvements to damaged municipal infrastructure as part of NexGen projects.

Resilience Opportunity: Resident Power in NYCHA campuses works when active groups in the neighborhoods independently organize to establish new revenue streams by working with local policymakers to leverage mechanisms for shared profit, resident ownership, or management into place. During the transfer of public property to private ownership and management rights, organized groups of residents can activate Resident Power for the payment of repairs or community priorities, whether they be new ventilation systems, or repairs for mold, or pest control, or addressing asthma concerns, or anything else. Resident Power can also be used to negotiate other arrangements such as revenue-sharing agreements. Revenues can fund resident capacity building and homeownership strategies, which further benefit communities at large.

Public services and activities, such as community participation in decision-making processes on NYCHA campuses, can help build trust and mend relationships between residents and NYCHA as an agency. In these ways and more, Resident Power can support agency goals as well as resident goals. There is not much existing precedent for the equitable control of shared money on NYCHA campuses beyond tenants’ associations’ current advocacy. However, NYCHA residents should be the pioneers within the next decade of Resident Power. They can use it as a strategy that aims to put power into the hands of the local community.

The three principles of our project will assist communities in addressing everyday needs, developing community buy-in and building up resources during times of crisis. This will in turn increase the social capacity, and the resilience, of individuals and communities. The focus remains on outcomes and the opportunity to scale strategies and resilience opportunities for maximum impact. Opportunities will greatly differ in each NYCHA community, as each strategy may be used to target community-centered systemic changes that best meet the needs of the community.

Next Steps

The aim of our work is to amplify work in vulnerable communities, and not impose solutions on residents nor communities already experiencing vulnerabilities. We seek allies who are interested in creating programming and who have had experience either in funding or the practical implementation skills needed to realize these projects. We aim to build on existing grassroots and community-led initiatives that are working to build community resilience and social reserves, and strategies that allow for proper investments in community resilience.

Authors ↓

Digser Abreu is focused on compliance monitoring of new construction, rehabilitation in line with local, state, and federal environmental regulations. She drives decisions through the impact of their actions on the environment, wildlife, and local communities. Digser has helped achieve billions in capital project contributions for public housing health and safety upgrades. She is focused on securing socially responsible investments in areas that need them the most.

Rhonda-Lee Davis is an urban planner who works to secure successful housing transitions for young adults who have aged out of foster care. She is passionate about the role affordable housing and financial inclusion play in promoting livable urban communities for all New Yorkers. She earned her Master of Urban Planning from CUNY Hunter College.

Dorraine Duncan is a city planner and policy analyst and provides analytical and research support for projects at the intersection of resilient infrastructure deployment, workforce development, and equitable economic growth. Prior to current role, Dorraine’s academic work focused on resilience for coastal and small island nations with a focus on the Caribbean. Her previous professional work supported projects focused on deploying innovative renewable technologies and developing workforce strategies to make New York city and state more resilient post-Superstorm Sandy.

Lydia Gaby is an economic development and urban planning consultant at HR&A Advisors. She leads projects that promote equitable economic development and resiliency and oversees large-scale participatory planning processes. Lydia supports a variety of HR&A services including program design, financial and organizational strategy, community engagement, and climate adaptation planning.

Gloria Lau is a landscape architect and urban planner, working at the intersection of public space, resilient infrastructure, and equitable design. She is currently a Senior Landscape Architect at Stantec overseeing design and construction of urban landscape. Gloria also serves as Director of Projects at Open Architecture/New York, where she implements pro-bono design projects for underserved communities.

Manuela Powidayko is an architect and urban planner specialized in climate adaptation. Her work is mostly focused on zoning and building code regulations that apply in areas prone to flooding, but she has also been working on efforts to assist with the pandemic-recovery in NYC. As an immigrant originally from Brazil, Manuela is passionate about helping individuals and communities develop self-determination so they can be more resilient after disasters.