In expanding our notion of a neighborhood park, we can invite others in and foster a spirit of shared responsibility.

By Frances Halsband

This is a big idea for small public spaces—spaces of less than an acre that show up on the map as public parks, private plazas, and odd-shaped lots at the crossroads of major streets. These little spaces can not only contribute to civic life and community vibrancy, but also pay their way. What should these spaces feel like? Green is great, but is it the only answer? “Keep Off the Grass” signs, fences, and benches may provide foliage and quiet spaces, but they do not invite the kinds of use that welcome a wide range of people who yearn for a diverse civic life. Midtown private plazas with monumental aspirations may forego the picturesque fences and benches, but they fail in their own way, because they can be off-putting to the woman on the street.

A neighborhood park should not only be a front porch and backyard for apartment dwellers, but also a place for creative civic uses. And by moving the decision-making authority for these spaces closer to the people who use them, we can cultivate a sense of ownership and responsibility. Community gardens already prove that local management works. Greenmarkets operate at individual sites, in concert with a sophisticated citywide organizational infrastructure. Both demonstrate the potential of directly connecting local people to local places.

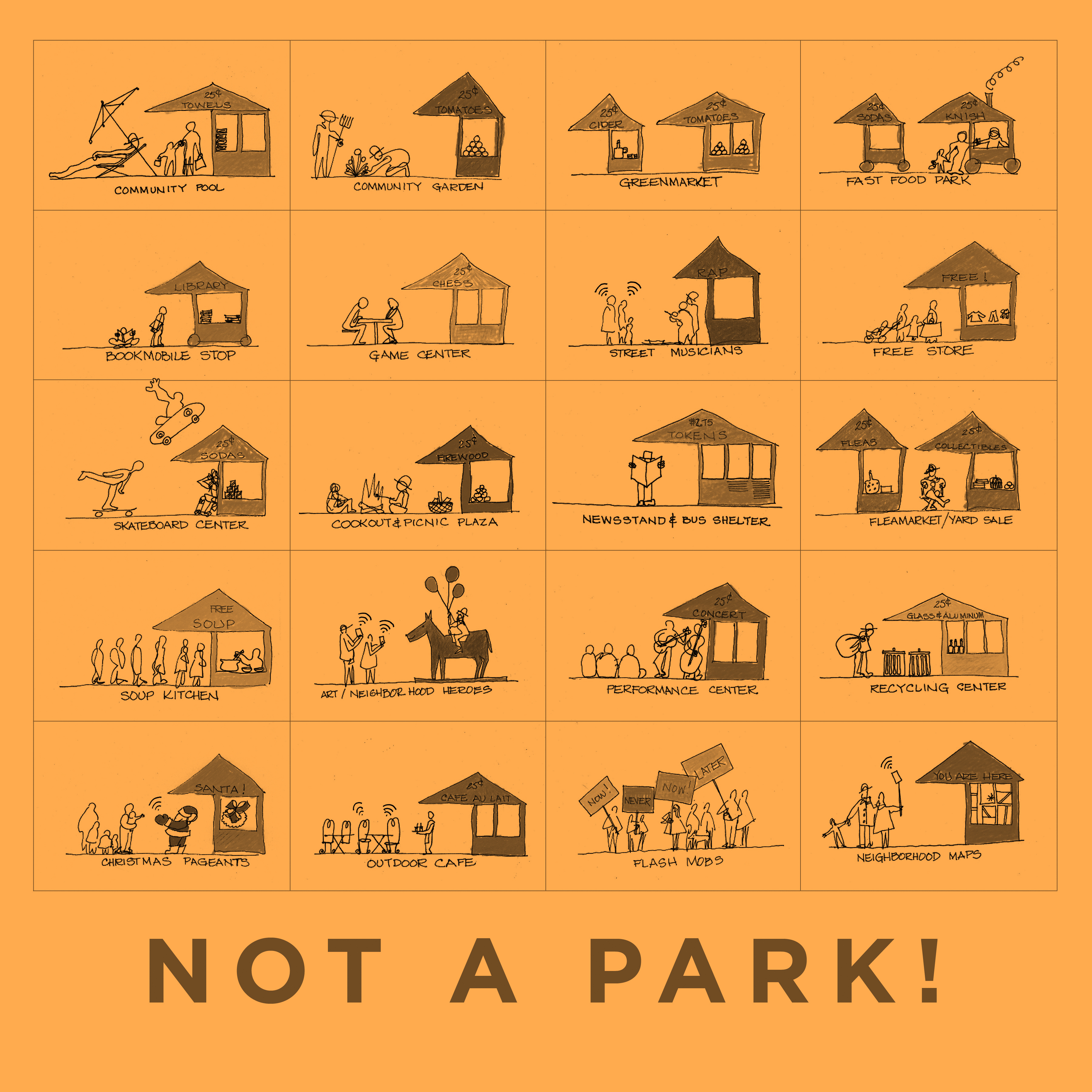

Community boards and block associations could take responsibility for renting and supervising neighborhood park spaces for a range of uses. Imagine cafés, performances, pageants, and neighborhood fairs. Pop-up retail and mini markets could bring in revenue to support other communal uses. Community events sponsored by local libraries, schools, or religious institutions would encourage each group to manage the space for certain times and uses.

Artwork and temporary installations that celebrate neighborhood heroes and values could be chosen by neighbors, instead of art imposed by distant bureaucrats. Instead of “No skateboarding, no bicycle riding,” the message could be: “Welcome to craft fairs, cafés, performances, games, and community fitness events.” Skateboarders and cyclists could even be welcomed for days of competition and recreation.

The management infrastructure should encourage neighborhood participation, reward sponsorship from corporations and nonprofits alike, and cultivate small-scale entrepreneurship. A system of short-term leases would keep activists and events constantly refreshed and ensure that a range of people is always welcome. And to help, the City can offer matching grants and incentives to the corporate owners of private “public” spaces, to encourage them to generate activities that welcome neighborhood workers, tourists, and other visitors.

The physical infrastructure to support such a wide range of events and uses must be flexible to be sustainable. Helpful features include areas with flat, hard surfaces; simple open-air shelters that keep out rain and sun; the availability of electricity and internet; and functioning restrooms. These spaces can host uses as diverse as flea markets, game tables, picnic plazas, soup kitchens, or tai chi.

If you call it a “park,” people who don’t get excited about grass will not come. Outdoor spaces need to welcome everyone and accommodate multiple uses—inviting entrepreneurship and stakeholders with an interest in maintaining them. These are small spaces with big potential.

–