The Urban Design Forum’s 2019 Forefront Fellowship, Turning the Heat, addressed ways how urban practitioners can advance climate justice principles across New York City. In partnership with the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency, Fellows surveyed neighborhoods, studied buildings, interviewed local and international stakeholders, and produced creative research on mitigating heat. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on creating circular economic and sustainable models in NYC, developing community resiliency within NYCHA housing, factoring design into preventative care, and establishing a climate first approach to housing which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

Read interviews with Nupur Chaudhury and Gretchen West to accompany this proposal, and view the full compilation of Turning the Heat proposals and interviews here.

by Jill Schmidt Bengochea, Cyrus Blankinship, Eileen Chen, Gregory Harasym, Catherine Joseph, Amritha Mahesh, Kathy Mu

Climate change poses unequal threats to communities, exacerbating health risks for those who are most vulnerable. Communities most affected by structural racism and poverty, with limited or non-existent access to health care, are already experiencing heightened risk caused by climate events, such as extreme heat events. Equitable health outcomes are necessary to achieve climate justice, and changes to existing policies can help achieve that goal.

—

⅕

—

Introduction

Extreme heat events kill more people in the United States than all other natural disasters combined. Between 2001 and 2011, New York City reported an average of 13 heat stroke deaths, 115 premature deaths due to extreme heat, 150 hospital admissions for heat-related illness, and 450 emergency department visits per year.1 Heat-related health complications are associated with the body’s inability to regulate temperature, which can cause heat stroke, heat cramps, heat exhaustion, and exacerbate respiratory diseases. The urban heat island effect, coupled with social conditions, creates disproportionate risk for New York City residents. Policy change is required to encourage practitioners in medicine, design, and planning to center health in mitigation planning, ultimately redefining preventative care to include the built environment.

Only 22% of health is attributed to genetics, while access to and quality of medical care accounts for another 11%. The remaining 67% of an individual’s health is attributed to social determinants including the built environment, social and economic factors, and individual behavior.2 Preventative health care should address all the determinants of an individual’s health, including the built environment.

In the context of extreme heat, the built environment is a significant factor in hospitalizations and deaths in urban areas. In more densely populated and highly impervious areas, the built environment—including buildings, streets, and infrastructure—absorbs and retains heat at greater rates, creating urban heat islands. These areas re-radiate this heat slowly at night. In New York City, summer nights are typically 7°F warmer than surrounding suburban areas; this differential can increase to as much as 10-20°F during periods of extreme heat such as heat waves.3 Because the built environment retains and re-releases heat, indoor temperatures remain dangerously high for days after a heat wave has subsided. This effect puts residents in further danger of heat-related health risks, especially at night.

In New York City, older adults, infants and children, undocumented and uninsured residents4, those with existing chronic conditions, residents in under-resourced neighborhoods that lack tree cover and adequate public space, and those who work outdoors are all at greater risk during periods of extreme heat. The City’s Heat Vulnerability Index (HVI), developed with Columbia University, identifies the neighborhoods most vulnerable to extreme heat.5 This index uses social and environmental factors to determine neighborhoods’ relative risk for heat-related death during and immediately following extreme heat events. The social factors used are poverty, as measured by the percentage of people receiving public assistance, and race. The environmental factors used are summer daytime surface temperature and green space, such as tree, shrub and grass cover. Neighborhoods with a heat index of 5 are considered most at risk, while neighborhoods with a heat index of 1 are less vulnerable. While the HVI identifies vulnerable neighborhoods, it is important to stress that residents across New York City are at risk of heat stroke and exacerbated chronic conditions due to heat.

Heat risks, particularly among susceptible populations, are expected to increase as extreme temperatures become more frequent. By the 2050s, New York City anticipates three times as many days above 90° and overall temperature increases of more than 5°F in the summer and winter months on a typical day.6 Without changes to the built environment, New York City can expect increasing rates of heat stroke, death, and hospitalization as temperatures rise, multiplying the financial and social costs of extreme temperatures.

Mitigating the growing threat of heat and reducing disparities in health outcomes requires a multi-faceted approach that leverages existing systems and policies. First, health practitioners and insurance providers must redefine preventative care, which plays a significant role in determining health outcomes, to include the built environment. Second, the city must incorporate the risks of heat in its policies to protect the health and safety of its residents. Finally, political leaders must commit financial support to implement the strategic, collaborative plans that community-based organizations are preparing in partnership with government agencies. With these targeted actions, we can develop policies and implement solutions that tactically address the health risks posed by climate change and the built environment.

—

⅖

—

Redefine Preventative Care

Climate change is already exacerbating chronic health conditions and amplifying the negative impacts of the built environment on health. While physicians are often aware of the effects of the built environment on health, they are not positioned to address underlying environmental causes. For example, in the case of extreme heat, rising temperatures exacerbate air pollution, while increased humidity creates conditions for growing mold, both triggers of asthma attacks. Medical professionals who respond to rising hospitalizations due to asthma during extreme temperatures are unable to address the conditions within patients’ homes that are triggering attacks.

To bridge this gap, the notion of preventative care must expand to include the built environment. The healthcare system must shift to a value-based payment system that emphasizes preventative measures including improvements in the physical conditions of the patients’ homes. Medical professionals should be empowered to prescribe opportunities for physical interventions in the home that are covered by insurance. These interventions should include air conditioning, HEPA filters, weatherization, and mold mitigation. Expanding preventative care to tackle environmentally-induced health triggers within the home could mitigate a patient’s risk to extreme temperatures and help reduce the need for emergency room visits and hospitalizations.

New York State has a precedent for expanding preventative healthcare coverage through partnerships between hospitals and community-based organizations: the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Program. DSRIP funding mandated health systems to work with community-based organizations and local healthcare providers through a Performing Provider System (PPS). A PPS managed the funding for system and infrastructure redesign and clinical and population outcomes. Each PPS created a network which included healthcare providers, community health centers, and community-based organizations to deliver on a holistic approach to healthcare.

In 2020, New York State was denied requests for continuing DSRIP, an unfortunate outcome since the program allocated insurance funding to preventative measures and underscored the potential for community-based organizations to facilitate connections between healthcare providers and residents. Preventative healthcare is crucial for community resilience in the face of large-scale emergencies, disruptions, or extreme events. Programs such as DSRIP offer viable precedents for how collaborations between healthcare providers and community organizations can offer climate-health resilience to New York’s most vulnerable communities.

—

⅗

—

Incorporate Heat in Existing DOB Policies and Connect to Funding

As temperatures rise and heat waves become more frequent, New York City’s housing stock will require improvements to reduce exposure to extreme heat for residents. To address the growing, silent risk of heat to residents, New York City should incorporate extreme heat into existing health and safety policies for buildings.

Dense blocks of aging, multi-family masonry buildings are typical across high-HVI neighborhoods, absorbing and retaining heat during periods of high temperatures and amplifying health risks. These buildings were designed to protect against a colder climate, not the increasing heat waves and rising temperatures of today. Currently, impermeable pavement and buildings with high thermal mass store heat when temperatures are high, then slowly release it back into the atmosphere. As a result, indoor temperatures remain dangerously high after the sun sets and for days after a heat wave subsides, causing complications for at-risk groups and increasing the likelihood of residents experiencing heat-related illnesses.

Updates to existing policies can bring multi-family buildings up to a standard that is safe amid rising temperatures. Furthermore, through enforcement, city agencies could connect property owners and managers to funding resources for renovations and retrofits with a mechanism to ensure compliance.

The City has made progress towards ensuring that apartments are free of health hazards such as indoor allergens, including with Local Law 55, passed in 2018. However, current enforcement mechanisms place the burden on the tenant to report their landlord to authorities, and many tenants are hesitant to report their landlords for fear of repercussions. Existing building inspection processes, such as the Facade Inspection & Safety Program (FISP), should be expanded to account for the climate-exacerbated health hazards evident in a degrading building envelope.

The Department of Buildings (DOB) created FISP to ensure owner accountability for the integrity of a building’s facade. Owners of residential and commercial buildings that are more than six stories are required to hire qualified professionals to inspect their facade every five years. This program was adopted to protect pedestrian foot-traffic from falling debris, and current inspection standards serve to monitor for the safety and health of the public. The expansion of FISP could account for the health of renters within multifamily buildings of all sizes.

Existing façade inspection standards have implications for extreme temperatures: inefficient or compromised building envelopes can allow in more heat during hot days or lead to areas of water damage that lead to mold and pests. These indirect effects, in turn, exacerbate respiratory illnesses and trigger asthma attacks. DOB should augment FISP by adding inspection standards that include climate-exacerbated health hazards and mandating improvements to reduce risk to residents. Currently, a similar process exists for regulating building cooling towers, which are registered and tracked for their compliance with Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) regulations for Legionnaires’ Disease prevention. It is critical to incorporate climate-exacerbated health hazards as they pertain to building envelopes into the existing safety review process to ensure the health of New York City residents.

In addition to identifying opportunities for physical improvements to multi-family buildings, funding for renovations and repairs must be made intelligible and accessible to building owners and managers. Once building owners receive their inspection report, DOB should provide a resource guide for city, state, and private funding programs for building retrofits and improvements.

New York State and New York City have a growing number of successful programs that could bridge funding for otherwise cost-prohibitive improvements, such as the New York State Weatherization Assistance Program and the Housing Preservation and Development’s Green Housing Preservation Program. Further, these improvements warrant tenant protections against rent increases as landlords make investments in their property. According to the Rules of the City of New York Section 3606-01, a building is considered to be substantially improved if the cost of improvement equals or exceeds 50 percent of the market value. It is critical for these facade improvements to be excluded from this stipulation to protect the renter from a rent increase, which will help to prevent displacement and ensure the existing tenant receives the benefit of any facade improvement.

This combination of renter protections, funding resources, and regulatory expansion would begin to bridge the gap between the built environment and preventative care in NYC’s privately-owned multi-family buildings.

—

⅘

—

Invest in Community-Based Plans

Neighborhoods that have physical characteristics and environmental conditions that exacerbate extreme heat conditions are often also home to lower-income communities of color. Factors such as impermeable surfaces with reduced evaporative cooling capability, dark surfaces with poor surface reflectivity, low tree cover, and waste heat from buildings, transportation, and infrastructure intensify temperatures in the public realm and increase the risk of heat-related illnesses during high temperature days. These neighborhoods are also frequently sites of burdensome infrastructure or clusters of heavy industry, which can greatly affect health outcomes, causing chronic health conditions such as asthma and other respiratory illnesses.

Recognizing inequities in health outcomes and disparities in public and private investments across neighborhoods in NYC, the City has made a conscious effort to provide resources and funding to communities with the greatest need, while also tailoring strategies to respond to specific populations, such as children and seniors. The Community Parks Initiative, Safe Routes to School, and Safe Streets for Seniors are examples of programs led by various City agencies that are making headway in improving the lives of all New Yorkers with particular attention to under-resourced communities. Identifying opportunities to partner with existing, successful programs can help to more effectively implement programs tailored to climate risk. For example, the aforementioned public realm improvement projects have several co-benefits that advance Active Design principles of promoting healthy neighborhoods and ensuring equitable access to vibrant public spaces. With current proposals for amending Executive Order 359, which created and enforced Active Design principles, there is an opportunity to expand the scope to include built environment interventions specific to climate-exacerbated risks and extreme heat.

As part of a holistic approach to neighborhood mitigation planning, localized built environment strategies can improve health outcomes and alleviate the public health impacts of climate change. For instance, the Take Care New York Neighborhood Health Initiative aims to confront the root causes of health inequity at the local level, bringing in community members to help identify how best to improve health disparities.

Building on this initiative, the City must convene CBOs, public health professionals, healthcare professionals, and built environment experts to create an actionable roadmap of coordinated, neighborhood-specific strategies to overcome environmental barriers, starting with HVI 5 neighborhoods. Political leaders should commit to developing and implementing the strategic plans that community-based organizations have already been preparing alongside government agencies as partners.

Solutions must include ways to increase vegetative cover, including incrementally replacing acres of asphalt surfaces in school yards and playgrounds. The City must identify resources to expand volunteer and stewardship programs and increase employment opportunities, in order to implement and maintain labor-intensive improvements. In areas with below-grade infrastructure constraints that preclude street tree planting, the City should partner with utility companies to identify alternate solutions and pilot new methods and technologies. The built environment must be incrementally transformed to address extreme heat through investments in the public realm that foster healthy environments for NYC communities.

—

⁵⁄₅

—

Conclusion

As temperatures in New York City rise and heat waves increase in frequency, the city will face increasing numbers of deaths due to heat, particularly among at-risk communities. The proposals above outline near-term interventions that can begin to mitigate the risks of extreme heat. These are not long-term solutions to the threat. However, they embed health as it relates to heat in existing policies through a framework that can evolve over time, adapting to changing conditions and strengthening as the climate continues to change. While these recommendations are intended for implementation over the five- to ten-year horizon, they establish a framework to allow for further change over the long term.

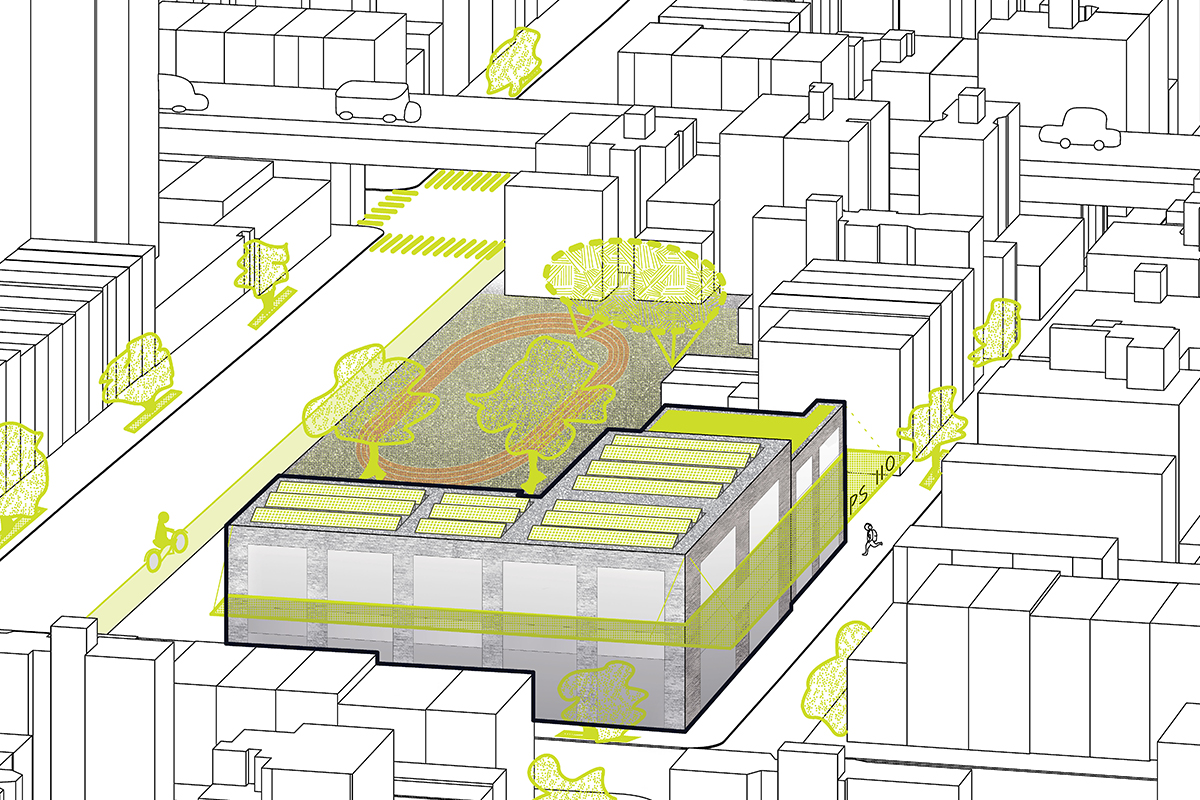

Header image caption: Replacing turf fields with grass and asphalt surfaces with more permeable materials can increase evaporative cooling and mitigate the heat island effect while also improving neighborhood-scale thermal comfort. Strategies at this scale should empower communities to prioritize and implement solutions in areas of greatest need. Credit: Forefront Fellows.