‘Complete Streets’ that accommodate all transportation modes—walking, cycling, transit and vehicular movements—are an aspiration of most city planning departments. New York City is no exception, having poured millions into infrastructure to support the growing number of pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders in the city while trying to maintain high levels of service for private, delivery, and livery vehicles. But as the city continues to grow, and with streets trying to be all things to all people, new conflicts between different users are sure to arise.

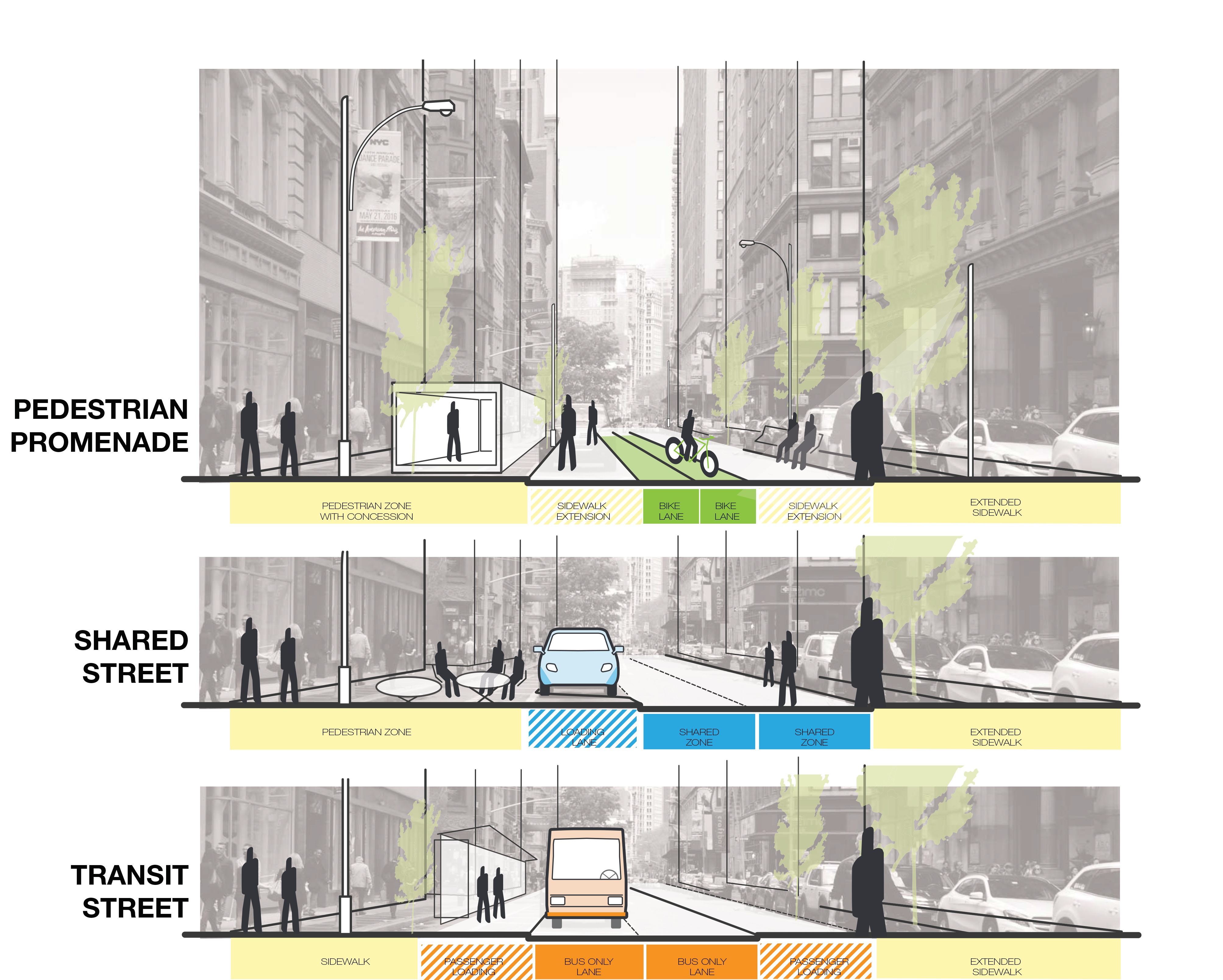

Rather than trying to serve all modes on major streets—where private vehicles are given broad access and bike and transit lanes are squeezed in whenever possible—it is time to reconsider NYC’s streets as a complete network that prioritizes and restricts modes on different streets.

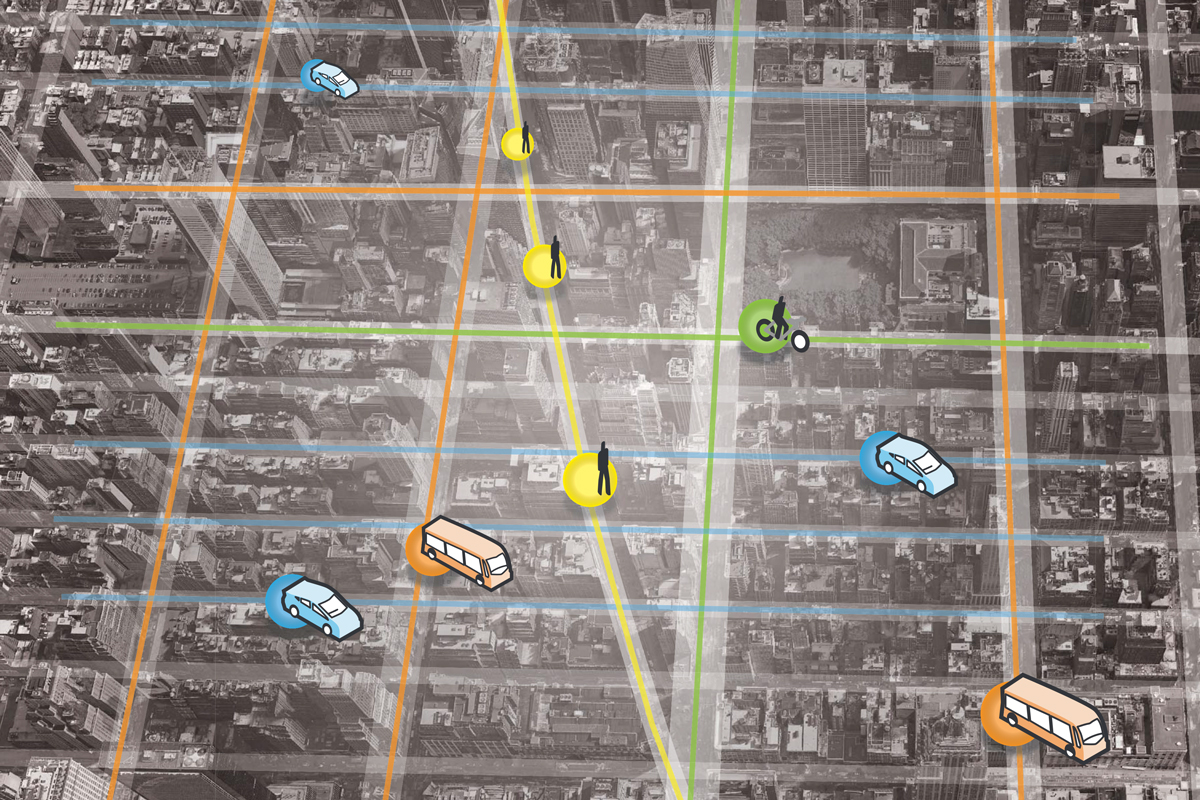

Possible street typologies in a new street network (Arup)

Cities around the world have been moving slowly toward this ‘Dedicated Streets’ approach for decades. In Melbourne, streets are classified into different typologies, which can be prioritized for different users—such as buses or pedestrians—at different times of the day, depending on which activity the planners choose to prioritize. London has created dedicated bus and bike corridors throughout the city—where the throughput of those vehicles is prioritized over others—resulting in growth in both bus passengers and cyclists. Copenhagen’s world-renowned Strøget was made possible through a strategic decision to reduce on-street parking by 2-3% per year over the course of the second half of the 20th Century. In Singapore, the city-state’s second 50-year plan is leading the Urban Redevelopment Authority to plan for a post-private car society as they prepare for the rise of autonomous vehicles, and maximize the use of space-saving forms of transportation, such as cycling, walking and public transport.

We don’t need every street to be ‘complete.’ We need a street network that works for everyone.

Imagine a new system of street management for New York, where dedicated corridors link up to create efficient networks for different users. Instead of Midtown’s endless gridlock, certain crosstown streets could be designed to move buses without impediment, while others could clear the way for general traffic during peak travel times. Deliveries can be accommodated in designated areas and during off-peak hours to avoid curbside conflict. Cyclists and pedestrians can enjoy vehicle-free streets from origin to destination.

While NYC faces severe space constraints when it comes to expanding mobility, we are sitting on the greatest opportunity for reprogramming street networks for alternate modes. After all, NYC’s own grid was once built around moving pedestrians, cyclists and horses rather than cars.

–