The Urban Design Forum’s 2018 Forefront Fellowship, Shelter for All, addressed the homelessness crisis in New York City by examining how to dignify the shelter system through better design and exploring the root causes of homelessness and housing precarity. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on how to address the prison-to-shelter pipeline, public bathrooms, public realm management, supportive housing, and racist housing policies, which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

Read interviews with Judy Whiting, Rita Zimmer, and Jonathan Marvel to accompany this proposal, and view the full compilation of Shelter for All proposals and interviews here.

By Ishita Gaur, Melissa Minnich and Heli Pinillos

Formerly incarcerated people are nearly ten times more likely to be homeless than the general public.1 Incarceration and homelessness are interconnected, and the need for re-entry services is imperative. Providing incarcerated individuals with access to early and continuous re-entry services will help reduce homelessness in New York City. There is significant overlap between the two populations and unfortunately too often people in need perpetually bounce from one institution to the next. We believe that providing re-entry services from the moment an individual is arrested is just as important as maintaining an uninterrupted liaison post-release within communities in order to lower New York City’s unacceptable rate of homelessness.

Leaving Prisons and Heading Straight to Shelters

In 2017, approximately 25,000 people were released from New York State prisons, 9,300 of whom were on parole. Upon release, 54% of these parolees went straight into a New York City shelter with only $40 and a single-ride MetroCard.2 These parolees made up 1 in 5 new shelter arrivals. Year after year, more people are being released from both State prisons and City jails. Furthermore, the City plans to shut down the jail complex on Rikers Island by 2026 and build four new borough-based jail towers in Queens, the Bronx, Manhattan, and Brooklyn; this will reduce the overall capacity of City jails from approximately 7,000 to 3,300 and result in a huge influx of shelter demand.3 It is increasingly difficult for formerly incarcerated individuals to connect to resources and support services, which often results in prolonged periods of homelessness and recidivism.

Challenges that Formerly Incarcerated People Face

Upon re-entry, formerly incarcerated individuals immediately experience the struggles of finding employment, housing, education, connecting with the community and learning about services available to them. They also carry with them the lifelong stigma of having been incarcerated, an invisible handicap that appears as soon as potential employers or housing providers ask for a work history or run a background check. Data has shown that unemployment rates among this population is almost 5 times higher than the U.S. national average among the general public, as it was in 2008. Black women with a history of incarceration are the most disadvantaged, with severe levels of unemployment as high as 43.6% while formerly incarcerated white men are the least with an unemployment rate of 18.4%.4

Stakeholders and Efforts to Help Formerly Incarcerated Individuals

Prior to the 1990s, few prisons provided services to support inmates’ re-entry back into society. Today, there is a diverse range of services such as case management, social services, vocational training, housing assistance, adult education, substance abuse treatment, and legal support. Each of these are now available at some correctional facilities across the country and offered by different stakeholders who advocate for this type of population, but challenges persist with the accessibility, preparation, programming, funding and timing of services.

Both New York City and New York State have re-entry programs for formerly incarcerated individuals which are not fully in sync. The New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) works throughout the state offering services in nineteen counties through special units known as County Re-Entry Task Forces (CRTFs), while the City works in the five boroughs through the NYC Diversion and Re-Entry Council and NYC Department of Corrections (DOC). Even with all these efforts, people are still being released from State prisons and heading to City shelters. Clients still need better ways to access proper job training, education, housing and family support.

Delivery and Accessibility of Re-Entry Services

Connecting formerly incarcerated individuals with re-entry services sooner leads to more successful re-entry. The average successful discharge rate for the period from October 2016 through March 2017 at state level was 65% as reported by DCJS.5 To improve this rate, individuals need to be identified and matched with the right services from day one, followed by an uninterrupted connection to services.

We have learned by talking to several institutions who have experience working within the criminal justice system that security in jails and prisons is a big deterrent in connecting with the incarcerated population. Designing a “soft-space” – which can serve as a way to invite service providers into secure prisons – is a difficult proposition and hard to implement in the current landscape of the criminal justice system.

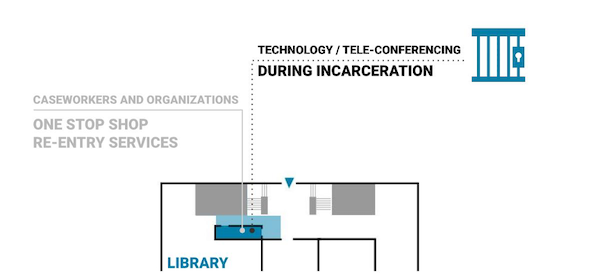

This is where technology comes in. Physically bringing the necessary resources for successful re-entry on-site to prisons requires a lot of time, human resources and security clearances. Technology makes it possible to provide inmates with all of the necessary resources without stepping foot inside a correctional facility.

Technology as a Conducive Connector with Clients

The Center for Urban Community Services’ (CUCS) Housing Resource Center has been providing information and access to housing for homeless people with psychiatric disabilities and other special needs for the past three decades.6 Through the program’s Reentry Coordination System (RCS) that started in 2009, CUCS holds pre-release interviews with individuals in prisons and jails through teleconferencing, allowing CUCS social workers to connect inmates with social service resources and supportive housing providers in preparation for their release.7 By using this technology, CUCS can connect directly with inmates without being limited by the security protocols typically found at prisons and jails, connecting them with the resources needed for a successful re-entry including access to housing.

Providing a platform for these organizations to connect in an uninterrupted manner will have a higher likelihood for success. It is crucial to start early, build accountability, and see it through to the end.

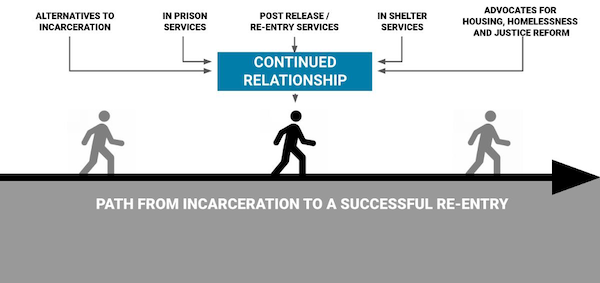

We believe there is need for establishing a continued relationship between services and the population, from the beginning through release. The existing network for re-entry services has become largely outsourced to private organizations, with each having a focus on a particular demographic, the kind of services, and the time during the journey that they are offered.

Providing a platform for these organizations to connect in an uninterrupted manner will have a higher likelihood for success. In the end, it all comes down starting early, building accountability, and seeing it through to the end.

Leveraging Our Libraries

We propose to leverage public libraries to serve as an incubator space for organizations that are providing services and resources to the homeless – specifically those with experience working with the formerly incarcerated – to come and dock. Libraries are inherently perceived as safe and welcoming spaces for all populations of the city. They serve as free education spaces, and thousands of New Yorkers without jobs, computers, or even the ability to communicate turn to them every day for the guidance to overcome adversity.

We recommend that every library have a designated section where trained caseworkers can settle in for the day and be available to meet and assist anyone who asks. They become a one-stop for all.

One of the biggest challenges identified in connecting individuals currently in the criminal justice system to services through in-reach within the criminal justice system is security. Interacting with inmates is difficult due to scheduling limitations, security procedures, and the additional time that it takes each caseworker to go through the process per appointment.

Libraries are already equipped with computer labs and internet services, where caseworkers can use teleconferencing to establish connections with individuals pre-release, thereby extending the access to services even sooner.

Libraries can play a central role in providing a platform for organizations that work in the criminal justice system re-entry services landscape to connect in an uninterrupted manner with clients pre-release, through the entire re-entry journey.

There are 216 libraries in New York City’s three library systems, each of which uniquely serves its own local community. Libraries are publicly accessible spaces that are welcome to all, regardless of race, class, or social position, and they see many citizens that would not set foot in a homeless shelter for several reasons, including mental health, police presence, previous negative experiences, stigma, etc.

By utilizing our City’s public spaces to connect incarcerated individuals with the resources they need most, we will be caring for our City’s most vulnerable residents while leveraging existing resources to sever the prison-to-shelter pipeline.

This will require collective effort with input and buy-in from all levels, including both New York City and State. The City and the State are both addressing this problem, but they are not unified in their approach. We believe that New York City’s Department of Social Services should lead this initiative as they house the City’s Human Resources Administration and Department of Homeless Services programs, which are both dedicated to fighting poverty and income inequality.

Conclusion

In addition to the proposals described in this essay and the important work many organizations and agencies are already undertaking to improve the chances of a successful re-entry for those with a history of incarceration, it is important to note that policy reform should still be a priority for affecting real improvement in the prison-to-shelter pipeline. Policy advocates need to continue championing the rights for the formerly incarcerated, such as expunged records, ending the New York City Housing Authority’s (NYCHA) Permanent Exclusion policy for those with a history of involvement with the justice system, background checks for potential employment opportunities, and others.8

New York City is a wonderful city because it is home to people of so many different colors, incomes, faiths, and communities, but none of us are home until all of us are home.

Authors ↓

Ishita Gaur is an Architectural and Urban Designer at Marvel Architects, most recently involved in a masterplan for Bellevue Men’s Homeless Shelter in NYC. She is interested in the social, economic and cultural conditions of cities and places, and their influence on urban interventions. She is also the co-chair of the Junior-Board for the non-profit Asia Initiatives.

Melissa Minnich is Development & Communications Coordinator at Fifth Avenue Committee. Melissa advocates daily for affordable housing and economic justice in Brooklyn. Previously, she worked in supportive housing for six years, working directly with chronically homeless tenants and advocating for tenants’ rights in New York City and State. Melissa holds an M.A. in Media, Culture, and Communication from New York University.

Heli Pinillos is passionate about improving access to affordable housing in NYC and helping underserved communities thrive. Aa a Project Manager at B&B Urban, he works building high quality affordable and supportive housing for homeless families. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Architecture from NJIT and Master’s degree in Real Estate Development from NYU.

Footnotes ↓

1. Couloute, Lucius. “Nowhere to Go: Homelessness among Formerly Incarcerated People.” Prison Policy Initiative, Aug. 2018, www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/housing.html.

2. Chappell, Dale. “New York’s Prison-to-Shelter Pipeline Is Poor Option for Parolees.” Prison Legal News, Nov. 2018, www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2018/nov/6/new-yorks-prison-shelter-pipeline-poor-option-parolees/.

3. Lewis, Caroline. “City Council Approves Plan to Shut Down Rikers Island And Build 4 New Jails.” Gothamist, Oct. 17, 2019, https://gothamist.com/news/city-council-approves-plan-shut-down-rikers-island-and-build-4-new-jails.

4. Couloute, Lucius, and Dan Kopf. “Out of Prison & Out of Work.” Prison Policy Initiative, July 2018, www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html.

5. “County Re-Entry Task Force Quarterly Activity Report.” CRTF Activities Report, Division of Criminal Justice Services, June 2017.

6. “Housing Resource Center.” CUCS, Center for Urban Community Services, www.cucs.org/housing/housing-resource-center/.

7. “The Path Home, Easing the Transition.” CUCS, June 2018, www.cucs.org/the-path-home-easing-the-transition/.

8. Working Group on NYCHA Permanent Exclusions, John Jay College Institute for Justice and Opportunity, https://johnjaypri.org/reentry-housing-initiatives-2/work-group-on-nycha-permanent-exclusions/.

Header image credit: Brooklyn Public Library