In this Practice Note, you’ll hear from our Global Exchange staff about what we’re learning as we build solidarity between leaders in New York City and other cities taking “big swings” at their housing crises. An immersive, 3-day study trip in September connected Global Fellows with leaders, key case studies, projects and policy shifts in Berlin.

By Clara Parker

“How do we replicate an innovation that’s embedded in a completely different political-economic-socio-cultural context?”

This question, posed by one of the 48 Global Exchange Fellows, identifies a challenge at the heart of the program. New York City is at a crisis point in housing its residents, and steps taken so far to solve it are woefully inadequate. The Big Swings fellowship aims to look outside New York City and the U.S. to find bold solutions to our housing crisis. But how might that work in practice?

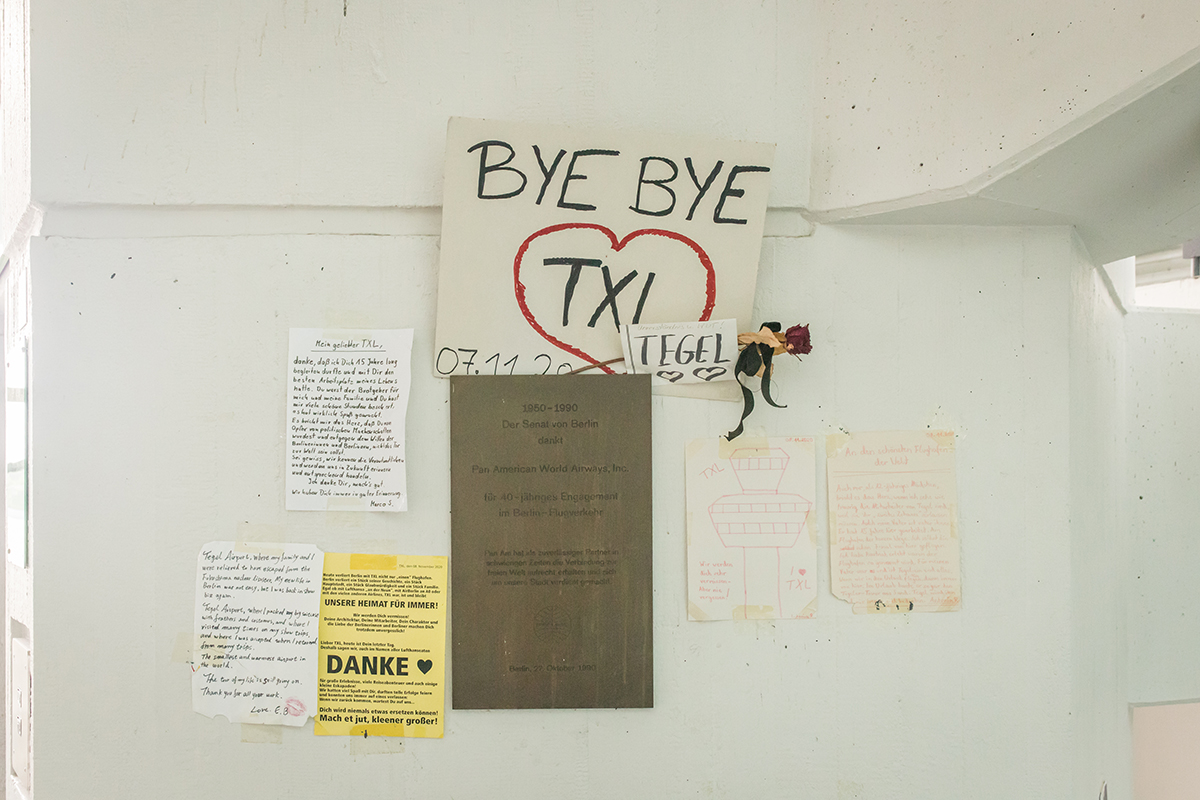

Seven weeks after orientation, the cohort landed in Berlin for a 3-day study trip. In preparation, we tempered expectations of what the trip could accomplish, emphasizing that our goal was not to cherry pick successful ideas and policies from Berlin to implement in New York City. Instead, we intended to widen the frame to consider the housing crisis a global crisis.

We opted not to visit a place like Vienna, a city hailed by many of our Berlin hosts as “the gold standard” in housing, and not just because another delegation from New York had already gone. We embraced Berlin as a city with its own problems, comparable to New York City in several factors. While Berlin is much smaller in population with a population of 3.85 million to New York City’s 8.1 million, it faces similar trends in migration. It has an even larger share of renters, at 85%, than New York City does at 69%. Both cities are challenged by low vacancy rates, with a rate under 1% in Berlin and just 1.5% in New York City. 40% of Berliners and 55% of New Yorkers struggle to pay their rent, caused in part by increases in rent and slow wage growth. In the last decade, rents in Berlin rose a staggering 100%. In the last year, New York City rents rose at a pace 7 times that of wages. Berlin has its own housing crisis to solve, as many of the leaders we encountered admitted. However, from elected officials to grassroots activists, the Berliners we met spoke of the crisis and possible solutions in very different terms from New Yorkers.

A recurring message we heard is that housing is a common good that should be afforded to everyone, regardless of income. This core value guides significant differences in Berlin’s approach to solving its housing crisis. Our hosts from various sectors of Berlin all emphasized the importance of public ownership of property, demonstrated in the “remunicipalisation” of land that was sold off to private developers after reunification in the early 1990s. Berlin has six government-run development companies and has mostly stopped selling land to private investors in favor of long-term leaseholds. Berlin has rent regulations that cover its entire housing stock, although regulations lack strong enforcement. Evictions are rare and heavily regulated against. Individuals receive subsidies to rent and/or invest in housing cooperatives. Robust civic participation — they strive to “put the party in participation” — is characteristic of Berlin, although imperfect in execution. Each of the 12 districts in the state of Berlin has its own Stadtwerkstatt or “center for diverse participation”, to encourage civic participation. We booked one, free of charge, to host our debrief workshop on Day 3 of the trip.

The model of the housing cooperative, “genossenschaft,” captured Fellows’ intrigue perhaps more than any other example in Berlin. It took a lengthy sit-down in the Ostseeplatz housing cooperative office in Kreuzberg to understand what a co-op is: a legal entity of 3 or more people who raise capital to buy or construct a building. One difference in how cooperative housing works in Berlin is ownership: members of Berlin co-ops own part of the entity, not the building itself. They pay “usage fees” (rent) to live in the buildings. If they choose to leave the co-op, they get back the exact amount they put in. Banks offer very low interest loans to cooperatives, and no matter the monetary investment, members of co-ops have equal say. Because most housing co-ops do not aim to generate huge profits, costs are kept down. As one of our hosts explained, the “return on investment is a social return.”

The value of housing as a common good, though championed by some U.S. and New York leaders in calls for social housing, is certainly not mainstream in New York City or the U.S. “How do we decouple value and profit?” asked one of the Big Swings working groups during our final event in Berlin, a perfect illustration of the contrast in thinking about housing in either city.

Exchange with another city goes beyond discovering what works there and translating it here. We can learn from how leaders in other cities think about comparable issues, how they approach solving their own problems (for better or worse) and how they think about their city in different terms and values. We can learn as much from each other’s challenges as from our success stories. The task now is to build upon the connections and conversations from Berlin and expand the exchange to other peer cities around the globe.