How can we make parks and public spaces more accessible to immigrant communities?

The Co-Creation of Neighborhoods: Equipping Communities to lead the Planning Process

As I write this paper, immigrants in cities around the country are being pushed out of their homes and their neighborhoods. As a child of immigrants, I heard stories from my mother and father, aunties and uncles, about the trauma of leaving their home country, their struggles in pushing roots deep in a new city, and making a home that is not their own their land. Many of them, including my parents, settled in cities, an ecosystem that did not necessarily welcome them with open arms, but tolerated them enough for them to build a life. Now, cities have become sites of conflict and displacement for immigrants, layering their trauma of arrival with an additional fear of displacement. Without this point of arrival, immigrants are left vulnerable and in a tenuous position, unable to build the life they envision for themselves and their families. Cities can design for arrival by rethinking the processes that lead to displacement, and reexamining the processes of community planning across the City.

East New York, Brooklyn.

There is no place more suitable to understand this than in East New York, a neighborhood that has one of the largest footprints of public space in the form of the Broadway Junction subway station, as well as a population that includes 30.7% foreign born, a 17.1% increase in that population from 2000-2011 (The Newest New Yorkers, 2013). This paper will focus on how immigrants can shape the planning processes around them to ensure that they can remain in place, facilitating the opportunity for immigrants to build roots and maintain their communities. Using the current situation in the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn as a case study, I will identify key pressure points and opportunities to include immigrants in the planning processes currently at play in neighborhoods across New York City, and to envision a new way of working between city agencies, residents, and stakeholders that is inclusive of all.

WHAT’S GOING ON?

On a Saturday morning in a church in East New York, I watched as community based organizations (CBOs) sliced oranges, set up Wi-Fi networks, and arranged tables and chairs. Residents filtered in, along with additional CBO partners holding poster paper and sandwiches. Leaders folded t-shirts that had drawings of individuals holding signs that said “East New York is not for sale”. Mothers brought their children, and guided them towards the back of the church, where there was a table set up for coloring, activities, and adult supervision. Organizers walked around hurriedly as they realized that the church manager had left without giving them the instructions on how to connect to the Wi-Fi. A volunteer hung a banner on the wall saying “Coalition for the Advancement of East New York”.

Catherine Green, head of Arts East New York, a key organization for the Coalition for the Advancement of East New York, began the meeting. She discussed why this was an urgent meeting: the NYC Economic Development Corporation a quasi-governmental had reached out to her. An advisory group was being formed, and EDC was convening them. They wanted to understand what the residents’ needs were in East New York and Cypress Hills in regards to Broadway Junction. As part of the EDC advisory group, she wanted to hear the needs of the residents.

She was followed by speeches from key leaders from Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation, the local YMCA, and other institutions, all of whom emphasized that this was an opportunity for everyone around the room, and that the improvements in the neighborhood should be what they all have been asking for years, not what a city agency thinks they need. One speaker said, now is the time to organize, stay committed, and stay focused on the asks and the needs the community has been hungry for decades.

After a couple of more speakers, and a screening of a section of the movie “My Brooklyn”, which showed the policies and practices employed by EDC and private developers for downtown Brooklyn, another leader talked about the historical processes that have been in place for decades that have resulted in East New York and Cypress Hills being disinvested in, ignored, and forgotten for so long. They talked about redlining, the effect of racist policies in denying family and individuals of color mortgages to purchase their homes.

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

Much has been written about the processes and failures of the rezoning of East New York. As it was the first rezoning triggered by the Mayor’s Housing Plan, the city struggled to figure out how to balance the needs and the mandate of the mayor to increase the number of units of affordable housing across the city, while also engaging with a community that has been largely ignored. Add that on to the fact that the city had been previously engaging with the community leading up to the rezoning via the Verde Summit (on the community side) and the Sustainable Communities study (on the city side), and the result was a relationship that many involved have labeled as a “complete 180 shift in priorities”.

WHAT’S AT STAKE

Broadway Junction, the site in question, is a transit hub where 3.2 million New Yorkers transfer between the Z, M, J, L, A and C lines. The intense congestion at the train station is compounded by the five buses at street level, as well as the Long Island Railroad one block away. This station is hardly commuter, resident, or pedestrian friendly: walks around in and into the station result in multiple dead ends into MTA parking lots, equipment storage area. Station hubs of this size and traffic, like Union Square, have much of the subway below ground, while the majority of Broadway Junction is above ground.

An analysis of major transit hubs in NYC highlights that Broadway Junction is one that was heavily populated and used, as well as being located in a neighborhood that has a large number of immigrants. The most recent Newest New Yorker Report shows that in East New York, 30.7% of the population is foreign born, as well as an increase in the foreign born population 2000-2011 of 17.1%. The Broadway Junction study, grounded in the East New York neighborhood, has the potential to support numerous immigrants to stay in place.

REFLECTIONS

Regardless of the direction or attitude, what is clear is that the power has, and continues to lie in the hands of city agencies. Whether it be the Department of City Planning, the Economic Development Corporation, the Parks Department, or private developers, space and public space are owned, controlled by, and shaped by non-residents of the neighborhoods in New York City. The majority of this statement lies in the fact that city agencies and private developers have the means to hire planners, designers and architects, individuals who understand both the language of space and place, but also individuals who are trained in the ways of regulations, approvals and certifications to get things built, renovated, removed, and rehabbed in the neighborhood.

What was described at the beginning of this paper was the attempt of community based organizations, organizations who are not trained in, nor paid to do design and planning work, to do design and planning work. Having these CBOs who are already stretched so thin to do the work of organizing residents AND gathering information about residents needs and desires AND collecting, collating and presenting it to EDC and DCP is a significant amount of work for CBOs who are well versed in meeting facilitation and organizing, but are not in urban planning, design and architecture, to advise EDC on the needs of Broadway Junction, is a request that is a lot to ask. Although CBOs have, and continue to rise to the challenge (see Sheridan Expressway, and diversion of Waste Transfer Stations), a better way is possible.

RETHINKING POSSIBILITIES: A PARADIGM SHIFT

Recommendation 1 (ongoing): Create a Master Plan for New York City.

197a plans are a tool, but have rarely been used as a tool for effective community planning in New York City. And if they have been used, they have rarely been implemented. Although New York City currently has a housing plan, this leaves out a clear vision for the city, the borough and the neighborhoods. A clear master plan for New York City will allow residents to understand the city’s vision for their neighborhood in a clear way and it will allow Community Planners to have a guiding document for which they can orient their work towards.

Recommendation 2 (Immediate Term): Create a Planning Help Desk in each borough.

New York City currently has a Zoning Help Desk, facilitated by Department of City Planning, which allows residents, developers, other city agencies and stakeholder to call in with specific zoning questions. The same can be created with a focus on planning at large, rather than just zoning.

Recommendation 3 (short term): Create a Community Planner Position in each borough.

This proposal was inspired by the model of the public defenders office: an office, supported by the City, in which a government appointed lawyer is appointed for those appearing before court who do not have the means to pay for a lawyer. Although they are employees of the government, they are required to operate with the plaintiffs best interest in mind. What would it look like if we had a similar role for planners? This would ensure that residents would have a planner, well versed in the language of planning and design, that is thinking about the residents (not the city’s) best interest. A role like this could be phased in over time: each borough could start with a single community planner. With time, that single community planner for each borough could evolve into a team of urban planners, utilizing the Zone Model pioneered by NYCHA REES department, and can culminate, over time, in a planner for each borough. This allows for a knowledgeable, individual, trained in planning, to serve communities in question, to remove the burden from CBO’s, and to foster the opportunity for a real conversation in co-creating public spaces, neighborhoods, and cities that work for all.

REFERENCES

1. Amato, Rebecca. “Board to Death?” Urban Omnibus, 12 Mar. 2018, urbanomnibus.net/2018/03/board-to-death/.

2. The City of New York, the Administration of Bill DeBlasio. “Housing New York-A five borough, 10 Year Master Plan.” 5 May 2014, https://www.nyc.gov/html/housing/assets/downloads/pdf/housing_plan.pdf.

3. The City of New York, Department of City Planning. “East New York Neighborhood Plan”. Last Update: 30 Oct 2017. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/plans/east-new-york/east-new-york-1.page.

4. The City of New York, Department of City Planning. “ The Newest New Yorkers”. Last Update: Dec 2013. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/data-maps/nyc-population/nny2013/nny_2013.pdf.

5. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 30 May 2014. “Implementation Plan for Sustainable Development New York-Connecticut Metropolitan Region”. https://www.sustainablenyct.org/SCIImplementationPlan20140602Final.pdf

6. Hu, Winnie. “A Tired Brooklyn Transit Hub Is Finally Getting Attention.” New York Times, 27 Nov. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/11/26/nyregion/a-tired-brooklyn-transit-hub-finally-getting-attention.html.

7. Lago, Marisa, and Maria Torres-Springer. “We Are Making Good on the Promise of a Strong and Sustainable Neighborhood.” City Limits, 6 June 2017, citylimits.org/2017/06/06/cityviews-we-are-making-good-on-the-promise-of-a-strong-and-sustainable-neighborhood/.

8. Murdock, Aubrey. The Domino Effect, 5 Apr. 2015, vimeo.com/126115082.

9. “NYCEDC, Borough President Adams, and Council Member Espinal Kick off Broadway Junction Working Group and Planning Study.” New York City Economic Development Corporation, 27 Nov. 2017, www.nycedc.com/press-release/nycedc-borough-president-adams-and-council-member-espinal-kick-broadway-junction.

10. Pratt Center Research “Cypress Hills Verde Summit Major Themes”. 11 Nov 2011, https://prattcenter.net/research/cypress-hills-verde-summit-major-themes-report.

Memory and Design Language in Establishing a Home

“Through dreams, the various dwelling-places in our lives co-penetrate and retain treasures of former days.”1

****

In his novel Open City, author Teju Cole, a Nigerian immigrant himself, tells the story of a young Nigerian doctor who walks the streets of New York City to unwind after the work day, observing the minutia of the city around him, reflecting on past experiences and life in Nigeria, and winding his way back to his apartment on the subway when he has wandered too far. Throughout the book, the city’s landscape evokes fleeting memories and sensorial connections to life in another country; he writes about these moments poetically:

The following day, returning to Sheep Meadow, on a circuitous route to a poetry reading at the Ninety-second Street Y, I noticed the masses of leaves dying off in bright colors, and heard the white-throated sparrows within them calling out and listening. It had rained earlier, and the fragmented, light-filled clouds worked off each other; maples and elms stood with their boughs still. Above a boxwood hedge, the swarm of hovering bees reminded me of certain Yoriba epithets for Olodumare, the supreme deity: he who turns blood into children, who sits in the sky like a cloud of bees.2

It is not a journey with a point A and a point B that Cole describes, but rather an intricately woven series of loops through the city infrastructure and a corresponding emotional journey as the protagonist seeks to establish his identity within his life and a new country. He says, “It was this way, at the beginning of the final year of my psychiatry fellowship, New York City worked itself into my life at walking pace.”3

The experience of landscape is a sensory, evocative, and emotional human experience on a conscious and unconscious level. The second we leave our houses, we experience weather, light and shadow, the materials of the path beneath our feet. We may travel the same routes again and again over the course of our days, familiarizing ourselves with that path – the street trees, the bench at a bus stop, the metal handle on the door to the subway station – or we may deviate from the pattern, seeking new routes, visiting a park to relax, attending an event in a plaza, or simply taking an alternate route to work; all the while, we are immersing ourselves in the built environment around us. New York City works itself into our lives at walking pace. When we leave a city and immigrate to a new one, this pattern begins anew. For a newcomer to New York, this is the way it can become a home.

****

Every immigrant has his or her own history, a personal sense of home, and a lifetime of memories and associations with various places he or she has been. There is a spectrum of emotions, undoubtedly, that comes with moving to a new country and encountering not just a new residence, but also facing economic challenges, cultural and language differences, and an unfriendly political climate. This spectrum is directly tied to an individual’s history and circumstance.

Case Study: Broadway Junction. Designers must familiarize themselves with the landscapes with which immigrant communities may be familiar as a starting point for establishing a common language.

That said, it is possible to trace trends and draw some conclusions, and it is important to look to studies that do so when beginning to discuss how best cities can serve immigrant communities, particularly public spaces that are required to serve many individuals and many groups at once. A 2004 study of how immigrants use Boston area parks describes many of the immigrants surveyed as:

…struggling to adapt to a new society in which they feel marginalized by language and cultural differences and at risk due to uncertainties around employment, education, and housing. It is in this context that people use public open spaces to gather in ways that remind them of their home country. In these spaces, they can meet friends and family facing similar challenges and offer one another advice and support.4

Design of public spaces is therefore an incredible opportunity to create a sense of belonging by weaving together these dreams of past, present, and future. “Put another way, the ‘where’ of our sensory experiences in the world have a profound influence on our ability to create individual and collective identities — to become, know, and name who we are…”5 This project asks: because of the sensory power of place and landscape, can a designer have a unique role in the process of Designing for Arrival? And with that, how does a designer, often from outside of the community, design places that are evocative for individuals and for groups who may be coming from vastly different backgrounds?

****

The only possible way to establish a design language that speaks to another’s experience, of course, is through dialogue, and there are immediate challenges in these conversations. For example, a public space design project is likely structured such that the immigrant community in question is the end user, but not necessarily the client. This means, then, that proper collaboration between the client, designer, and end users must be fostered. Within this collaboration, then, there are challenges that are particular to working with immigrant populations, such as language and cultural barriers. We are fortunate in New York that there are several groups working to create various resources for breaking down these barriers, such as the People Make Parks project by Hester Street Collaborative and Partnership for Parks, which uses a series of games and interactive tools to engage community members and park users, and the Partnership for Parks “Guide to Immigrant Outreach in Parks,” which is a series of recommendations directed at parks groups for fostering participation among nearby immigrant populations.

Once dialogue is established, there is a final hurdle, which is that designers also often speak a language particular to the profession. It is often easier to have conversations about how many bathrooms a park needs or about how the lights at the ball field are broken or about how the park should support a diversity of activities reflective of the diversity in the neighborhood. It can be more difficult to have a conversation about the more visceral qualities of landscape such as light and shadow, the sound of wind in certain tree canopies, the warmth of certain materials, or the narrative of a path unfolding before you and how that feels different when it is lined with trees versus a tall hedge versus adjacent to an open field, simply because these may are often things experienced but not articulated. It is particularly challenging when the designer and the immigrant communities aren’t necessarily familiar with same landscapes and therefore don’t share common references.

****

Design is a visual discipline, and the process often begins by gathering images – precedents of other projects that might have applicable characteristics that might be useful as part of the design. It is these images that allow designers to talk to one another – and clients – and to have conversations from which design is born. Typically a design project looks to geographically proximate projects as precedents, projects that might be similar in size or program. This project proposes that a designer should, in whatever way possible, examine precedents from the countries of origin as a starting point for a conversation about visual language.

Two contemporary examples of this design methodology are Rios Clementi Hale’s Grand Park in Los Angeles and BIG, Topotek1, and Superflex’s Superkilen in Norrebro, Copenhagen. These are notable as well given that the design was based in research and conversation, but the ways in which that was translated into visual language are very different.

Case Study: Broadway Junction. Through conversation and gathering visual precedents, surprising and meaningful interpretations may be found.

Grand Park, a civic public space in the heart of downtown LA, bills itself as “The Park for Everyone” and found its design language through the examination of the flora of the countries of origin to find overlaps with plants that would be appropriate for the southern California climate. The designers established a planting palette of native and exotic plants that would be representative of the diverse cultural makeup of the city. Signage throughout the park explains gives context to the plant design. Additionally, in this study, they noticed that of all of the flowers in the origin countries, there was only one color that was common to all: hot pink. The custom furniture throughout the site is finished in that exact hue, a sly nod to the precedent study.

The designers of Superkilen took a different tactic. Home to more than 60 nationalities, Norrebro is one of the most ethnically diverse neighborhoods in Copenhagen. The community outreach took a quite extensive and hands on approach: five groups of different community members took trips all over the world, following particular memories of people from the neighborhood in order to find and source specific objects. These were either transported directly to the site or a replica was made. Each is displayed with a plate adjacent describing the object and a story on an online app that explains the origin of the item. It is, in effect, an outdoor museum of internationalism, placing representative objects on display and celebrating the stories of their origins. The juxtaposition of the different objects, out of their original context, creates new meaning for a new place.

****

…a designer who wants to make a home that can be loved cannot simply tabulate a list of physical features that have been shown to be pleasing to the human perceptual apparatus. The design must understand the client’s history, the kinds of dwellings that they have known so far, and the kinds of things that happened to them in these places of memory.6

****

This is not to say that there is one “right” outcome to these conversations. Nor is it to advocate for replication or appropriation as a design solution. Rather, it is to suggest that there is something magical in learning about the landscapes and public spaces of the countries of origin. Using this understanding while designing will yield a result that is meaningful and possibly surprising.

Designers play a unique role by being able to help facilitate dialogue about visceral experiences in the built environment. Let’s change the typical conversation.

This is not to say that there is one “right” outcome to these conversations. Nor is it to advocate for replication or appropriation as a design solution. Rather, it is to suggest that there is something magical in learning about the landscapes and public spaces of the countries of origin. Using this understanding while designing will yield a result that is meaningful and possibly surprising.

The aforementioned examples are vibrant, visually striking, gathering spaces that have been researched with respect to the users’ history. It could be argued, however, that some aspects are more successful than others, particularly as we return to discussing the more visceral aspects of designing for arrival. For example, the use of plant material Grant Park would certainly be reminiscent of the textures, colors, smells, and shadows that a newcomer might remember, but a pink bench is not necessarily evocative of the flowers it represents unless you know the story behind it. Collecting objects from various countries and gathering them in Copenhagen acts as a reference to a specific place and time, but can also be seen as a reduction of a culture into a symbol and an exoticization of an object, rather than a meaningful gesture toward an immigrant population. This is not simply to criticize, but to say that perhaps this methodology could be furthered with ongoing conversation and adaptive responses even after construction.

In conclusion, we need to keep talking. And in these conversations, we cannot lose sight of the unique position that the designer brings — a means to establish a design language in order to design for memory, design for the senses, design for arrival. We also cannot lose sight of the larger goal of equity in public space design and the goal of establishing systems that can both benefit and benefit from immigrant communities. Park and public space design and the designer’s role in the process is simply a single piece in a vibrant network of civic, economic, and political systems that allows our city to serve all people.

REFRENCES

1. Bachelard, Gaston, The Poetics of Space, New York: Penguin Books, 1964.

2. Cole, Teju, Open City, New York: Random House, 2011.

3. Ellard, Colin, Places of the Heart: The Psychogeography of Everyday Life, New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2015.

4. Lanfer, Ashley Graves and Madeleine Taylor, “Immigrant Engagement in Public Open Spaces: Strategies for the New Boston,” Barr Foundation, 2010.

5. New Yorkers for Parks, “Parks for All New Yorkers: Immigrants, Culture, and NYC Parks,” New York, 2008.

6. Partnership for Parks, “A Guide to Immigrant Outreach in NYC Parks,” New York, 2011.

7. Samson, Kristine and Jose Abasolo, “The Trace of Superusers From Santiago Centro to Superkilen in Copenhagen, https://www.mascontext.com/tag/superkilen/

8. Schama, Simon, Landscape and Memory, New York: Random House, 1995.

IN CONVERSATION WITH:

Julia Lindgren, Hester Street Collaborative

Sarita Daftary-Steel, East New York resident and board member of United Community Centers

Inbetweeners: Young Adults, Immigrants and Public Spaces

How we use public space is personal. Where we decide to sit, play, and congregate, is largely driven by how a space makes us feel and whether we feel welcome. Creating inclusive public spaces means designing spaces that meet the needs of a variety of people. New York City has world class public spaces, but do they meet the needs of all users? What about young adults, those who’ve outgrown playgrounds but aren’t necessarily welcomed in all spaces? How are public spaces serving them, and how does immigration complicate notions of accessible public space?

We know that New York City is a city of immigrants, but we often don’t think about the fact that New York is a city of young immigrants. Over a third of New Yorkers are immigrants and just under a half,1 or 45%, of New York City’s foreign-born population is between the ages of 18-45.2 In addition, there are approximately 73,000 New Yorkers who are DACA recipients or DACA-eligible.3 New York also has a significant number of young immigrants who enter the country alone. In 2013, there was an estimated 58,000 undocumented minors living in New York State, second only to Texas. And yet, even though young adults represent a significant portion of the City’s population, it’s hard to think of public spaces that cater to them.

The way we typically understand immigration and the politics of public space becomes complicated when we consider the needs of young adults. Spatially, teenagers are primarily allowed to occupy educational facilities and their place of residence.4 Yet, both spaces are likely highly regulated. In addition, a newly arrived immigrant may be in a crowded living situation or might have challenges accessing school because of documentation issues.1 Several school districts in the New York metropolitan area have school requirements that include showing an original birth certificate, state identification, or immigration paperwork in order to register a minor for school.5 These requirements can make navigating the school system more challenging as an undocumented minor or the child of undocumented parents.

Public spaces become all the more important in this context because they are often spaces of freedom and personal growth. Unlike navigating housing, school, or other regulated spaces that might require documentation, or have certain culturally or socially specific mores, public spaces like parks, sidewalk benches, and plazas don’t require those formalities. For the most part, public spaces are what we make of them, they’re the quintessential “third place”.6 For most young people, regardless of immigration status, having a third place to shape identity is critical. These are the spaces where they can encounter other young adults from a variety of backgrounds who might challenge or reaffirm ideas of self.7 They are also spaces where social bounds can be developed and strengthened, and where critical social infrastructure can be formed. The magic of these spaces is that this infrastructure is developed without adult supervision and without having to spend capital.

Unfortunately it can be challenging to linger in public spaces because of design choices or the policing of space, particularly for youth of color and undocumented youth. If we reflect back on the history of Broken Windows and Stop and Frisk, most of the policing was built on targeting people perceived as more likely to commit criminal behavior. According the Vera Institute of Justice, at the height of Stop and Frisk policy in the early 2010’s, roughly half of all stops involved individuals between the ages of 13 and 25.8 These stops occurred in public spaces like parks and sidewalks. At the same time, other types of third spaces, like shopping malls, aren’t necessarily welcoming to large groups of young people. In 2010, the Atlantic Terminal Mall in Downtown Brooklyn enacted new policy that forbade groups of 4 or more people under the age of 21 from lingering in the mall.9 While the policy was enacted in a private space, and was ostensibly put in place to deter large groups from overwhelming stores, it also points to the way in which the operators of private spaces likes malls or fast food restaurants—traditional third spaces for young people—still have the legal right to exclude certain demographics.

As an urban planner, native New Yorker, and the child of immigrants, I’ve spent a lot of my life and career in exercises of translations: trying to make complex ideas, be it zoning, land use, or run of the mill information, accessible. When thinking through these complex issues of public space, I wanted engage with young people living through the tensions. I had the opportunity to talk to teenagers at Grover Cleveland HS in Ridgewood currently thinking through the challenges of immigration. The class was working in partnership with Y-PLAN (Youth – Plan, Learn, Act, Now) a national program that allows young adults to pitch design/policy solutions to local government. The students were working on creating apps to help NYC immigrant’s access job and housing resources as well as provide general advice on navigating the City. The class was predominately first generation and second generation immigrants from Latin America, South Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.

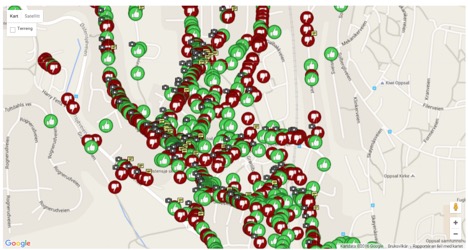

Students at Grover Cleveland High School mapping out welcoming vs unwelcoming spaces.

We spent the class discussing their experiences in public space and how they would make spaces more accessible for young people, especially young immigrants. We did a mapping exercise using their high school and the surrounding area to map out safe and welcoming spaces, versus spaces they felt excluded. Even though their school is next to a park, many students highlighted the space as being unwelcoming, in some cases because of its proximity to the school, or because there was not much for them to do in the park. Oftentimes, non-public spaces like restaurant parking lots were highlighted as good public spaces because they allowed for social gathering without being under the surveillance of school.

Map of welcoming vs unwelcoming spaces.

When I asked the students how they would change spaces to make them more accessible, most of their recommendations centered around improving the accessibility of public spaces: whether through translation so that newly arrived young people know about the history of public spaces, through community gatherings where neighbors can share food to learn about each other, or through the creation of social networking apps, where young people can connect to teenagers with similar interests who live in their neighborhood to meet up in public spaces. The students’ recommendations and experiences in public spaces point to a need for creating more points of entry into the planning and design process for young people. While the planning and design profession has many tools for community engagement, there remains a significant “blindspot” in architecture and planning when it comes to teenagers.4

City of Oslo Traffic Agent App.

There are examples of successful local and international youth engagement around public space planning. In 2006, the Sara D. Roosevelt Park Coalition worked with People Make Parks to conduct a community planning process for Sara D. Roosevelt Park, an eight acre park at the intersections of Chinatown and the Lower East Side. The park’s user base reflects this confluence of neighborhoods with kids and adults playing handball and basketball, and seniors doing Tai Chi in the early morning. People for Parks put on a day-long visioning event, gathering feedback from 600 young people. There was a variety of ways to participate (scavenger hunt -site surveying, adult and teen design charrettes, model making, etc.) and provide feedback in a variety of formats and languages.10 The City of Oslo, funded an app for grade school children that allows them to provide feedback on pedestrian and traffic conditions on their way to school.11 Making sure that community engagement processes foster co-creation for a variety of participants and creating more mobile-friendly tools can go a long way in allowing young people to voice their opinions about public spaces.

If a young person is the intended user of a space, they should be involved in the design process. Many city agencies like the School Construction Authority, Department of Parks and Recreation, and the Department of Transportation, spend a significant amount of their capital budgets on the construction and rehabilitation of spaces that will likely be occupied by young people. Oftentimes there is a community engagement component that accompanies these capital projects, but because the demographics of civic groups and community boards, the residents involved in community engagement activities may not reflect the current demographics of immigrant communities or a diversity in age.12 As urban planners and designers, we should strive to create community engagement practices that include the voices of people who aren’t just the usual suspects when it comes to engagement. We should be creating more lines of communication for people who can’t attend a town hall event or a working group meeting.

Creating partnerships with local middle school and high schools can be an innovative way to include more young voices in the planning and design process, and also introduce more young people to the urban planning and urban design, both professions which have traditionally lacked diverse representation.13 High school students are typically required to take some sort of civics course before graduation, but it’s unlikely that the class touches on urban planning policy, even though government plays a significant role in shaping the built environment. There are so many decisions that go into shaping the built environment, but if you’re a young person or an immigrant, the decision-making process can seem abstruse and inaccessible. In communities undergoing major planning processes that include investments in public space, the creation of a youth advisory groups at a local area schools or partnering with a civics or government class, can be an effective way to get more young voices in the planning process, and also introduce more young people to planning and urban design. It can also be a way to get older immigrants involved in planning. A working adult may not have time to go to a public meeting about a park, but if their children are actively involved in the planning and design process they then have access to all the latest news.

We can also create more interactive and mobile friendly community engagement platforms. According to the Pew Research Center, approximately 73% of teens have access to smartphones.14 As we work on creating more inclusive community engagement approaches, special attention should be given to web and mobile platforms that make it easier to provide feedback, particularly for residents who may not feel safe in engaging with government through more formal channels.

Signage can go a long way in creating a sense of ownership and invitation into public spaces. Traditional NYC Parks Signage creates a sense of consistency and wayfinding when it comes to open space, but what if there was a way to celebrate these spaces and make their uses clearer to immigrants? We should encourage more signage that welcomes immigrants into public spaces and that encourages joy in public spaces.

Lastly we have to become more comfortable with young people occupying and shaping public spaces. Lingering in a public space is not loitering, and frankly we should rethink the definition of loitering as a whole. The Yes Loitering Project is a collective of teenagers in the South Bronx who spent 2017 collecting extensive research teenagers’ feelings on policing, street harassment, and accessibility of public space.15 In general many of the teens felt like there aren’t welcoming spaces for teenagers and far too often, they’re even criminalized in public space.

As a planner, I think about the lifetime of planning decisions. Oftentimes when we design a public space or facilitate a zoning action, the outcomes of those decisions won’t be fully realized for several years or even decades. Young people are the ones that get to experience the final product of our decisions. As such, they should be involved in shaping the decision making process. For young immigrants, and young people in general, having agency in public space is all the more important: public spaces can be important sanctuary spaces outside the watchful eye of family members and institutions, and they are the spaces where identity, friendships, and social networks are formed and nurtured.