By Gretchen Dykstra

The heart of Manhattan was reborn when the Times Square Business Improvement District (BID) was established in 1992, led by Gretchen Dykstra. Dykstra went on to serve as Commissioner of Consumer Affairs under Mayor Bloomberg, and was the Founding President of the National 9/11 Memorial Foundation. Today, she lives in the Hudson Valley where she is working on her third book and tutors inmates at the Fishkill Correctional Facility through the Bard Prison Initiative. Here, Dykstra recalls the Times Square BID’s innovations, and pays homage to the sanitation workers who were the cornerstone of the area’s renaissance.

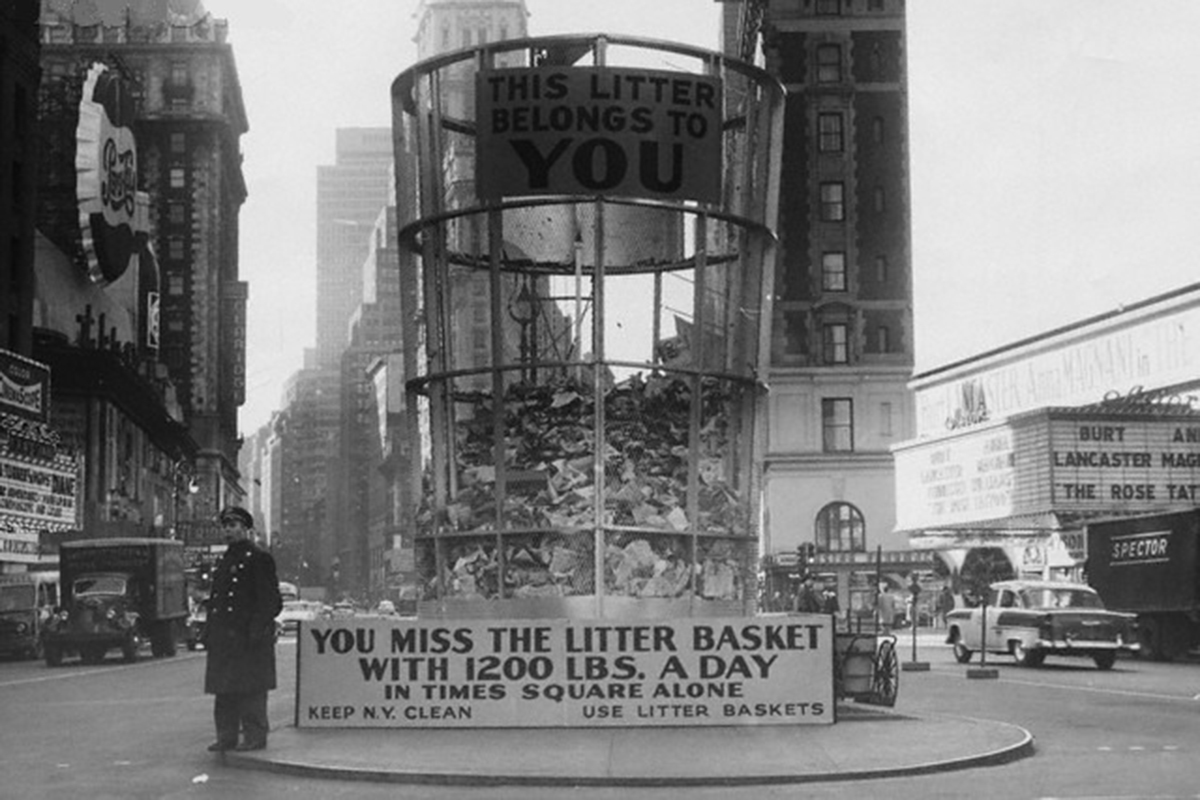

The Times Square BID began operations in January 1992 when I rode into Times Square with a sanitation supervisor just after midnight. Times Square was raunchy, gritty, and unnerving. Hotel rooms, theater tickets, and restaurant tables went begging. Office buildings stood bankrupt; even One Times Square, the iconic building that owns “the ball” was in receivership. Forty-two porn shops set the tone, and the sidewalks were repulsive.

Led by the future publisher of the New York Times, the organizing committee of the Times Square BID identified the needs, the boundaries, and the future assessment formula. We had a two-pronged mission: Make Times Square clean, safe and friendly—and then tell the world that Times Square was back. While many mothers gave birth to the new Times Square, the BID’s sanitation workers were key to the achievement of the BID’s two-pronged mission.

They were the stars of our show. Working in two shifts from 5 a.m. to 9 p.m., they were the faces of the BID, always dressed neatly in their bright red uniforms, designed by a famous Broadway costume designer and featured in a New Yorker column. Their work was endless, our promotion of them relentless.

We had twenty-five full-time sanitation workers, starting at $9 an hour with family medical benefits, a 401(K) match up to 3.5 percent of their earnings, and two-weeks vacation—the exact same benefits as senior staff. But the BID boundaries were the busiest 50-square blocks in the entire City, and we needed more workers.

So we struck a deal with Project Renewal, a well-respected social service agency. The BID hired another twenty-five workers, all from Project Renewal’s residential treatment center in Fort Greene. Supported by Medicaid, the men lived together for 12 months, undergoing intensive individual and group therapy, assuming responsibility for all aspects of their daily lives, and preparing to return to work. Project Renewal sent us those men who were ready to work, and we paid them $7 an hour without benefits. We trained them, supervised them, and reserved the right to “fire” anyone who did not meet our standards. In return, whenever we had an opening for a “regular” sanitation worker, we only hired graduates from Renewal House. That gave us the opportunity to see how individuals performed and gave them a powerful incentive to succeed at their treatment.

Although no one grows up dreaming of being a street sweeper, our sanitation workers saw polishing sidewalks as a victory, a sign of achievement, not failure, and because of that they were superb employees.

And thanks to the creativity of our marketing and operations staff, they became our media stars. Remember: Tell the public things are getting better! We were unrelenting. Once we threw a picnic in the middle of Times Square—complete with red checkered table cloths—with our sanitation workers, Department of Sanitation brass, and television cameras to celebrate “streets so clean you can eat off them.”

On another occasion, we swept up cigarette butts and counted them one by one to convince property owners to place ashtrays outside their entrances. The television cameras loved that story—and we got the ashtrays.

We turned some of our sanitation workers into part-time photographers. Sometimes nighttime employees of restaurants or delis did not bag their garbage properly, leaving the sidewalks a mess for the morning crew. Hesitant to “report” a Times Square business to the Department of Sanitation inspectors, we trained a few sanitation workers to use 35mm cameras. They took photographs of the strewn garbage, and then, armed with the photographs, we visited the manager, sure she’d want to know, lest we report the recurring violation to City inspectors. It worked. And when a photograph of our photographers appeared in a local newspaper, which we sent to our property owners, all our businesses knew we were watching, and the public knew we cared.

We bought the first mechanical sidewalk sweeper, and asked Tony Randall, the original Felix Unger from The Odd Couple, to record a message on it. “Honk, honk, this is Tony Randall, move over and let me clean the sidewalks of Times Square.” That was a big hit on the evening news, and a source of constant amusement for Times Square visitors. And so on, and so on.

Maybe this sounds like social work, not public space management—but at our core we believed that neighborhoods that work together are neighborhoods that work, and to make Times Square clean, safe and friendly meant starting internally and working outwards. Our sanitation crew—some of whom are still there today—put their lives back together and together we put back Times Square. Plus we had lots of fun together–not an insignificant consideration!