How can we integrate the needs of immigrant communities in regional planning?

A Toolkit to Spatialize Immigrant Experiences

A Toolkit to Spatialize Immigrant Experiences

INTRODUCTION

Immigration is typically understood at distinct scales: the global, the multinational, the national, and the local. At the global scale, the number of international migrants worldwide reached 258 million in 2017, an increase of almost 50% since 2000,1 driven by the pull of unequal economic and social opportunities across borders, and the push of natural disasters and political upheavals. At the multinational scale, flows of people from the Middle East and North Africa into Europe has had profound effects on the relationships between European nations. At the national scale, debates over immigration have featured prominently in recent public discourse in the United States, with over 25 percent of respondents to a major poll listing immigration as one of the top five problems for the government to address in 2017.2 At the local scale, there are sanctuary cities and immigrant neighborhoods, as well as local examples of xenophobia. These scales of understanding the phenomenon of immigration in turn informs the scales of responses: United Nations resolutions, multilateral treaties, national laws, local policies.

However, key dynamics of immigration are best understood in a regional context. The American Planning Association defines a region as “a geographic area that transcends the boundaries of individual governmental units but that shares common social, economic, political, cultural, and natural resources, and transportation characteristics.”3 A regional consideration of immigration is increasingly important in the United States, as immigrants are now less likely to be concentrated within a particular urban core: the proportion of immigrants living in suburbs grew from 56 percent in 2000 to 61 percent in 2013, and three-quarters of immigrant population growth in that period occurred in the suburbs.4 Immigrant dispersion and suburbanization presents new challenges, as immigrants may be less likely to form critical masses for social support and political power, and small municipalities may be less capable to address immigrant needs.

Furthermore, trends related to the movement of people, goods, and information across large distances call into question whether a region must necessarily be contiguous. With decreasing costs for air travel, some immigrants with the means make regular visits to their countries of origins; for many, instant phone or electronic communication is a daily part of life. With the intergenerational clustering of immigrants with a shared origin, specific multimodal connections occur, as in the case of northern Puebla, Mexico and Newburgh, New York: the relationship has led La Noria, Puebla to be nicknamed “Noria York,” and Newburgh, the “other Puebla York” (the first being New York City, no longer the sole major destination for immigrants).5 Even more strikingly, financial connections between immigrants and countries of origin bring distant localities into close economic interdependencies, with almost $140 billion in remittances flowing from immigrants in the US to origin countries in 2016 alone.6

To define an appropriate region, and to understand that region from immigrants’ perspectives, traditional, authoritative data sources are not sufficient. Past generations of planners have articulated the need to have direct communications with individuals and communities affected by plans, especially for groups that are typically underrepresented. This principle applies especially to immigrants, whose familiarity with their new homes, lack of proficiency in the local language, and legal status may all lead them to be underrepresented to those with the authority to collect, publish, and use major data sources.

TRADITIONAL AND ALTERNATIVE DEFINITIONS OF PLANNING REGIONS

Public planners operate within specific jurisdictional boundaries. For instance, city planners for New York City exert their influence over the five boroughs: looking at housing availability, the distribution of public space, where to expand and improve transit, and the like. However, a planner’s agency largely ends at the borough boundaries. The resulting policy, guidelines, statutes, mappings, and other products of planning draw their power from the political structure standing behind them, yet begin and end at their jurisdictional edges.

Public planners operate within specific jurisdictional boundaries. For instance, city planners for New York City exert their influence over the five boroughs: looking at housing availability, the distribution of public space, where to expand and improve transit, and the like. However, a planner’s agency largely ends at the borough boundaries. The resulting policy, guidelines, statutes, mappings, and other products of planning draw their power from the political structure standing behind them, yet begin and end at their jurisdictional edges.

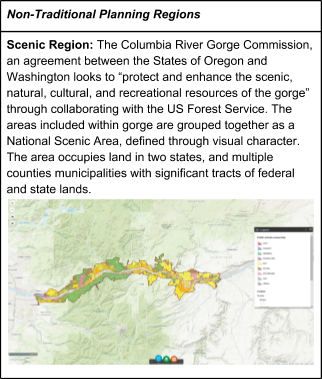

While this system works quite well for planning issues whose scope can be managed at a single jurisdictional level, the division of planning authority by governmental body encounters challenges when it becomes tasked with issues that cross political boundaries. The limits of this structure may be best evidenced by strategies developed by ecological science and environmentalist critiques. Watersheds, habitat corridors, contaminant clean-up, scenic regions, and climate change all defy political boundaries and demand coordinated planning approaches at multiple levels and across multiple territories. Not fitting neatly within political territories, intergovernmental agreements or non-governmental advocacy groups form to address a given issue.

While this system works quite well for planning issues whose scope can be managed at a single jurisdictional level, the division of planning authority by governmental body encounters challenges when it becomes tasked with issues that cross political boundaries. The limits of this structure may be best evidenced by strategies developed by ecological science and environmentalist critiques. Watersheds, habitat corridors, contaminant clean-up, scenic regions, and climate change all defy political boundaries and demand coordinated planning approaches at multiple levels and across multiple territories. Not fitting neatly within political territories, intergovernmental agreements or non-governmental advocacy groups form to address a given issue.

Similar to these environmentally determined planning boundaries, some cities have established planning bodies that reconsider the historical artifacts of their political boundaries, in effect redrawing the map to allow for a more holistic approach to the issues they face. Portland, for example, established an overlay regional district occupying the jurisdictional space between county and state levels that encompasses portions of three counties and twenty three cities to manage the growth of urban areas and preservation of open space in the Portland metropolitan region.7 The boundary is under the jurisdiction of elected officials and is understood to be the only political entity of its kind in the country. The Regional Plan Association (RPA) studies and advocates for policies in the metropolitan region of New York City, drawing in multiple states, counties, and cities to address issues that defy historical jurisdictional boundaries. However, unlike Metro, the RPA is not an elected government body and does not have any official authority.

As a group of Urban Design Forum Forefront Fellows focused on the intersection of regional planning and contemporary immigration, we take inspiration from the above examples of freeing issues from the political boundaries they are set within.

CROSS-BOUNDARY LIVING

Many people live their lives across political boundaries, living in one municipality, working in a different county, and worshiping in a third state. Access to key services, including but not limited to reliable transportation and secure housing typically enable cross-boundary living; simultaneously, cross-boundary living can also provide access to these same services, creating a virtuous feedback cycle. For some traditionally marginalized groups, such as immigrants, this loop can be vicious. Living life in a way that crosses political boundaries can surface challenges and require circumnavigation that are not typically considered by mainstream planning actors. This is especially true for immigrants who are poor, undocumented and/or have limited English language abilities. For example, consider a newly arrived undocumented immigrant who lives in a neighborhood of a suburban town that is miles away from New York City. Their housing choices are limited by their economic circumstances. But living in a far flung suburban town could make it challenging to access a job in NYC or another commercial node where there is a greater likelihood of finding a job, especially one that doesn’t require formal work authorization. Specifically, the sprawled layout of their suburb could make the last mile journey from a transit station to their home especially challenging as the immigrant balances not being able to drive legally with very limited local bus services. These are challenges that planners can help alleviate. While planners’ and designers’ influence on federal policy like immigration reform is typically limited, it is squarely within our remit to shift the ways local and regional public services reinforce limitations or create opportunities for marginalized communities.

PROPOSAL FOR IMMIGRANT ENGAGEMENT

Our proposal consists of the following elements:

1. Develop mapping strategies that help redefine regional boundaries from immigrants’ perspectives and identify immigrants’ priorities and needs.

2. Engage immigrant communities through formal planning groups throughout the New York City region. This should begin with one group for each of New York City’s five boroughs.

The attached Toolkit for Immigrant Engagement is an initial attempt to define an engagement process that can support the creation of policies, plans, designs and proposals that improve the lives of immigrants. At an individual level, these spatial extents comprise a particular immigrant’s zone of influence. Our hypothesis is that when the extents of multiple individuals living in a particular community with a defining characteristic (e.g., undocumented and poor) are merged, the aggregate extent could suggest a version of a region’s boundaries from that immigrant community’s perspective.

Institutions like the RPA, which already grasp the fundamental idea that people live in ways that defy administrative and political boundaries and are committed to improving life for those across the region, are well situated to pioneer methods for querying and understanding these non-traditional boundaries. In the development of their Fourth Regional Plan, the RPA engaged in formal contractual relationships with community organizations in order to ensure that the plan appropriately reflected the perspectives of communities whose voices are often unheard. One reflection of community groups participating in the process and RPA staff was that there are some issues that are very important to immigrant communities but are not traditionally considered planning issues. The group struggled with the best way to integrate these critical issues into the Fourth Regional Plan. For example, while the planning process readily engages with questions of where new transit routes might need to be built, it is traditionally less involved with questions of how quickly fare prices increase or the discrimination experienced by passengers on local bus routes. Creating the opportunity for immigrants to map their own experiences of navigating the region could help make space for some of these issues that are not always considered in planning processes.

Organizations that support immigrant communities could also benefit from a visualization of immigrant communities’ boundaries because it might help them to understand, communicate and/or advocate for the true spatial reach required of their work. Citing scholars and immigrant advocates, a NYTimes article published in March 2017 noted, “the kinds of services that immigrants rely on– low-cost legal help, language classes, interpretation and public transportation– have not kept pace with demand and remain disproportionately concentrated in big cities.” Mapping what immigrant communities’ current zones of influence look like, and the ways that may be limited by access to affordable transport options, affordable housing, and existing services can help trigger public, targeted responses to improve these same services- potentially expanding what those zones of influence look like.

TOOLKIT FOR ENGAGING IMMIGRANTS – PDF ►