To restore biodiversity and address environmental injustice, New York City should transform decommissioned energy facilities into new waterfront infrastructure.

By Charlotte Barrows, Hannah Berkin-Harper, Andrew Buck, Victoria Dearborn, Kirk Gordon, Kevin Kim, Harsh Shah, Lee Stark, John Surico, Somto Uyanna

The Need

New York City is a megacity situated at the confluence of various geological and ecological systems, including fresh and saltwater environments and major migratory routes. These systems are vital for sustaining a diverse array of plants, invertebrates, birds, fish, and mammals across numerous habitats, all coexisting with over 8 million residents.(1) But that balance faces various external threats, like overdevelopment, hostile architecture, invasive species, and pollution, amongst others. Nearly 70 percent of the city’s surface is impervious, earning it the moniker “the concrete jungle.”(2)

Natural ecosystems play a crucial role in supporting human life and mitigating climate change. They capture carbon, manage and purify stormwater, reduce urban heat, prevent erosion, and shield communities from storm surges. Additionally, ecosystems contribute to food and fuel production and ensure a steady supply of freshwater.(3) Biodiverse ecosystems are linked to improved human health by lowering the risk of disease transmission and enhancing both physical and mental well-being. (4)

Biodiversity is often undervalued, and must become a central priority in planning and design to address the climate crisis. Biodiversity practitioners and advocates face several challenges, including difficulties in scaling efforts citywide, sourcing native and diverse plants, lacking data and metrics to measure impact, and limited funding from public and private sources to support and manage these essential spaces.(5)

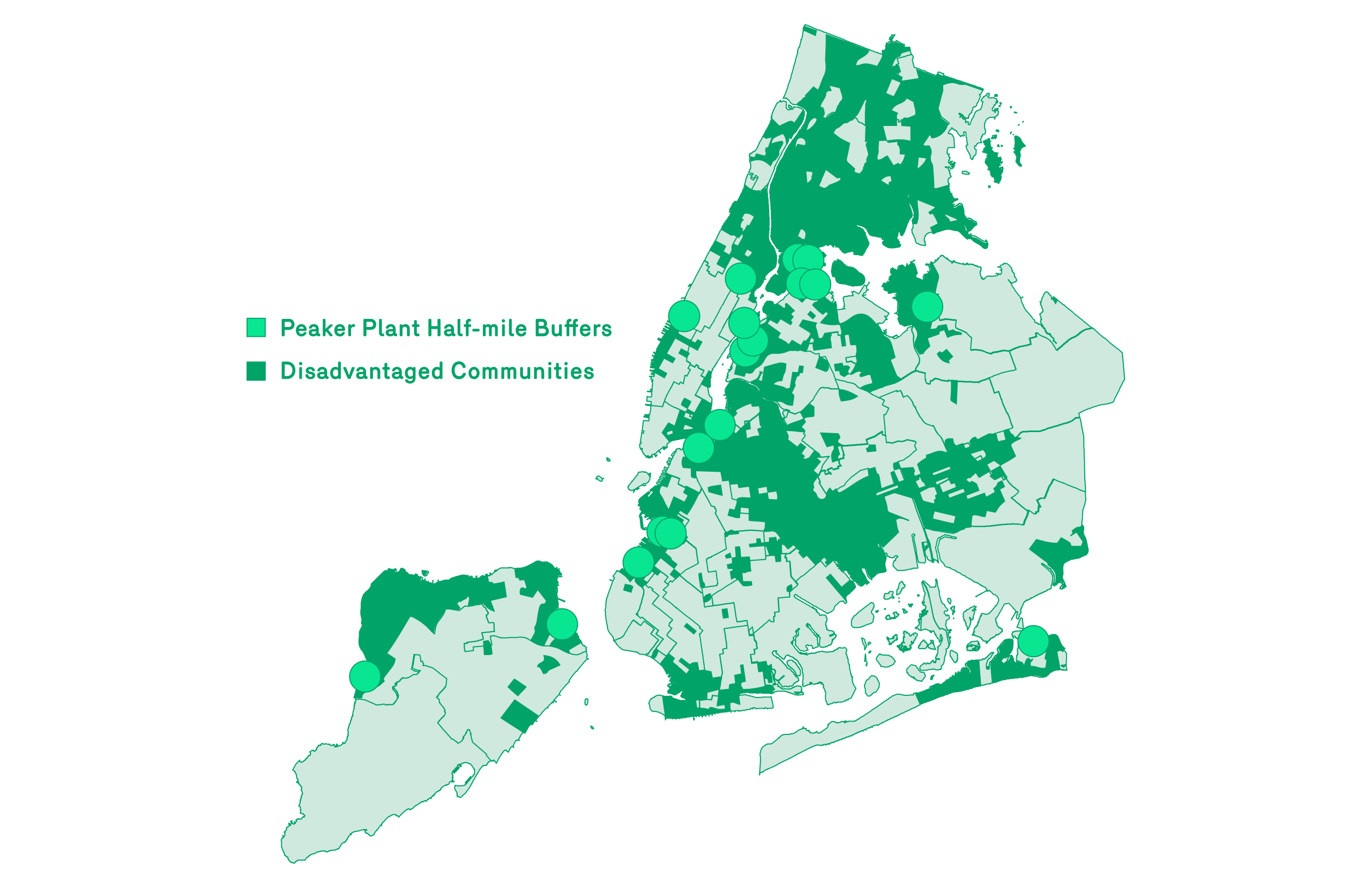

At the forefront of New York’s environmental justice efforts is the gradual decommissioning of fossil-fueled peaker plants. Under the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) Peaker Rule, energy companies must actively work toward decommissioning these sites and repurposing them for renewable energy. These plants, which previously supplied fossil fuel-based electricity during peak demand periods, emit harmful pollutants into the neighborhoods where they are located – often low-income, Black, Latine, and immigrant communities – and contribute to habitat disruption. Nearly all the waterfront neighborhoods housing these peaker plants are classified by state and federal agencies as “disadvantaged communities,” bearing the disproportionate environmental and health burdens of climate change.(6)

The Vision

To restore biodiversity and address historic harms in environmental justice communities, New York City could transform polluting energy facilities into new models of waterfront infrastructure through the Plant to Plants initiative. A public-private-community partnership with power plant operators, government agencies, and environmental justice organizations could guide strategies that deliver environmental, community, and climate benefits across the five boroughs.

With the DEC’s Peaker Rule in effect, there is an opportunity to align the transition of these sites into clean energy facilities with strategies that incorporate natural ecosystems. Additionally, New York City has a chance to address both health and environmental concerns while providing critical open space and community access. These power plants not only emit harmful pollutants into the local air, but also, restrict public access to the waterfront. By focusing on waterfront peaker plants, Plant to Plants can help advance the goals of New York State’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act and New York City’s EJNYC initiative.

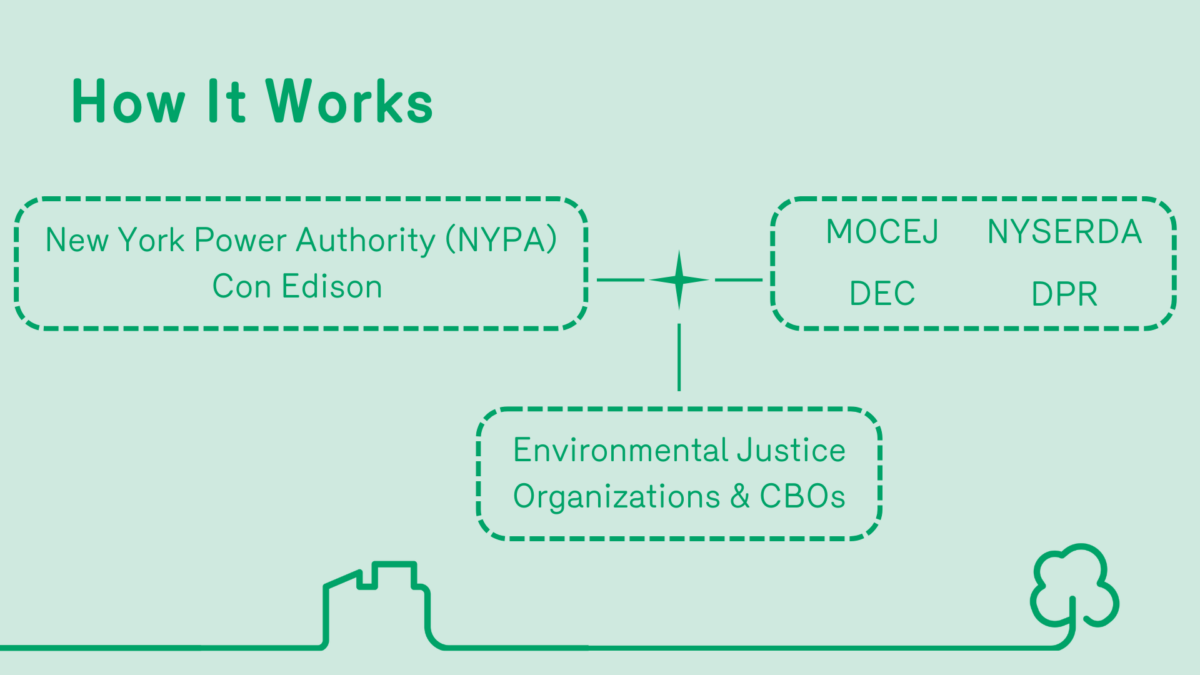

The initiative would begin by engaging with power plant operators, starting with sites managed by the New York Power Authority (NYPA) and Con Edison. Since these properties are largely privately owned and managed, any pathways for future development hinges on private stakeholder buy-in. Relevant city and state agencies – such as the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice (MOCEJ), NYS Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), and NYC Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) – along with meaningful collaboration with local environmental justice organizations can support in planning the transition of these sites over the coming years. Various strategies can be implemented to enhance biodiversity at these energy sites and in every neighborhood across the city:

→

Create stronger baselining and data analysis to measure biodiversity change over time.

- On peaker plant sites, power plant operators could establish partnerships with higher education institutions to support ecological assessment and monitoring, replicating Con Edison’s biodiversity baseline research with SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

- City agencies including the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), the Office of Technology and Innovation, and civic tech groups like BetaNYC could map ecological networks in every neighborhood and make biodiversity datasets accessible on NYC OpenData.

- Agencies, like MOCEJ, DPR or DEP, could develop a Citywide Biodiversity Plan and report changes over time to inform programs, while addressing potential “green gentrification” through New York City’s Displacement Risk Map.

→

Build a ‘net positive case’ for ecological infrastructure through new neighborhood planning strategies.

- A strategic task force comprising city and state agencies in partnership with academic institutions can monitor phytoremediation, or the process of using plants to clean up contaminated environments, in every neighborhood to measure inequities and access to the benefits of biodiversity.

- Mandate city agencies like the Department of City Planning (DCP), Department of Transportation (DOT), and DPR to incorporate planning strategies that consider networks of biodiversity at nodes (like peaker plants, parks, and public plazas) and corridors (like shorelines, streets, and railways).

- Identify “ecological priority areas” to guide city agency pilots on specific sites, guide resource allocation and develop incentives for publicly owned sites.

→

Integrate biodiversity and equity principles into land repositioning and land redevelopment strategies on power plant sites.

- Power plant operators could craft RFP (request for proposals) requirements and scoping language that mandate specific tasks and expertise to integrate biodiversity and public access into the comprehensive design of projects.

- Leverage city, state, and federal technical assistance programs for brownfield assessments for projects that prioritize biodiversity through nature-based solutions.

- Mandate the alignment of site planning, design, and implementation of power plants with citywide climate resiliency plans and programs.

- Strengthen and amend exterior improvement requirements on industrial properties enforced through local building and zoning codes (i.e. DOB, DEP, and DCP) and statewide (i.e. 2020 Property Maintenance Code of New York State – Section 302: Exterior Property Areas)

→

Establish a local seed and plant supply chain on waterfront peaker plant sites.

- Plant to Plants partnerships can develop on-site seed collection and propagation programs that focus on locally adapted native plants, climate-resilient species, as well as endangered or at-risk regional ecosystems.

- Expand native plant procurement through publicly accessible nurseries that provide materials and education to local communities, partnering with programs like NYC Parks’ Greenbelt Native Plant Center.

- Leverage resources from the NYS Native Seed Program to finance nursery development and identify stakeholders for ongoing operations.

→

Collaborate with community organizations to create job training pathways focused on ecological infrastructure maintenance and management.

- Partner with local nonprofits and conservation groups to develop training programs for skills related to biodiversity management, propagation, sale, and distribution of native plant species.

- NYS DEC or NYCEDC could explore developing financial incentives for local hiring to support ecosystem stewardship.

- Amend the NYCEDC’s Green Economy Action Plan to consider job growth in biodiversity-focused sectors as an essential economic metric.

→

Coordinate with existing environmental education programs and leverage sites for citizen science and living lab initiatives.

- Power plant operators could collaborate with city agencies to develop curricula for pilot peaker plant sites, building on existing programs like the Greenbelt Native Plant Center’s Seed Increase Program.

- Conduct outreach to local schools, community-based organizations (CBOs), and businesses to encourage participation in these educational programs.

→

Make decommissioned peaker plants publicly accessible and empower community-based local stewardship.

- Delegate local residents as “stewards” through programs such as the NYC DEP Rain Garden Stewardship Program and NYC Parks Stewardship Program.

- Leverage the transition of peaker plant sites to support localized plans, such as UPROSE’s Green Resilient Industrial Plan.

- Use pilot sites to streamline technical assistance for community organizations in securing public and private grants.

Act Now

To transform each waterfront site at scale, New York City will require both political will and community buy-in. In the coming years, Con-Ed could pilot a demonstration project at a peaker plant to test these concepts, with partnership with and support from city and state government agencies, local and state elected officials, environmental justice organizations, and power plant stakeholders like NYPA and Con Edison.

An ideal site for this pilot would possess the following qualities:

1.

Lies at the intersection of industrial and high-density housing zoning for maximum human health and social impacts

2.

Overlays within an existing Environmental Justice Area (EJA), which identifies a low-income community area especially vulnerable to climate hazards

3.

Contains an existing and/or upcoming legislative structure for its transition to a decommissioned and environmentally remediated site

4.

Situates within local community coalition channels that can be consulted for community visioning, community needs, and local stewardship

5.

Neighbors public waterfront spaces that qualify under the Waterfront Revitalization Program, which contains guidelines for biodiverse shoreline plantings

Case Studies

| PROJECT | OVERVIEW | IMPACT | RELEVANCE |

| Test Plot (California) | Nonprofit focused on site-specific restoration gardens and ecological stewardship through research and teaching. | Established over 15 ecological restoration sites in California, serving as living laboratories and community-driven spaces. | Demonstrates how small-scale, community-driven projects can drive broader land restoration and foster ecological care. |

| Bronx River Foodway (NYC) | The city’s only ‘edible food forest’ on public land, launched in 2017 at Concrete Plant Park in the South Bronx. | Integrates edible plants into the landscape, addressing food deserts and supporting community engagement through gardening and foraging. | Model for urban biodiversity and sustainability by repurposing formerly industrial spaces into functional, edible landscapes. |

| Gowanus Canal Conservancy (NYC) | Community-based steward of the polluted Gowanus Canal, leading volunteer projects, education, and green infrastructure development. | Advanced ecological restoration with rain gardens, zoning enhancements, and native plant management, aiding canal remediation and rezoning. | Highlights the potential of grassroots efforts to transform polluted urban areas into thriving ecological spaces. |

| UPROSE (NYC) | Grassroots organization addressing environmental and health impacts of waterfront peaker plants in central Brooklyn. | Advocated for renewable energy transitions, launched Sunset Park Solar, and established the PEAK Coalition to replace harmful peaker plants. | Illustrates the link between environmental justice and public health, driving systemic change through local activism. |

Charlotte Barrows

Senior Associate, Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects

Charlotte Barrows is a Registered Landscape Architect and LEED Accredited Professional with over 15 years of professional experience. Charlotte’s projects at NBW focus on restoring cultural landscapes: Forsyth Park in Savannah, GA; Jay Heritage Center in Rye, NY; Mount Cuba Center in Hockessin, DE; and Olana State Historic Site in Hudson, NY.

Hannah Berkin-Harper

Design Lead, Streetlab

Hannah Berkin-Harper is the Design Lead at Street Lab, a nonprofit that creates and shares new designs and programs for public spaces in New York CIty. She designs furniture and objects to support programming that brings people together in the public realm. She previously worked as Senior Industrial Designer at Karim Rashid’s studio and founded HBH Design, a consultancy focusing on projects involving environmental sustainability and public space. Hannah teaches at Pratt Institute.

Andrew Buck

Senior Urban Planner & Technologist, VHB

Andrew Buck’s decade-long career in urban planning and design has focused on utilizing technology to tackle complex urban challenges. His expertise lies in deploying technologies, including data, model based design, and geospatial analytics, in community and climate planning. Drawing on experience in Asia and North America, Andrew has led projects including climate action and adaptation, smart communities, infrastructure modernization, and neighborhood development.

Victoria Dearborn

Program Specialist, The Nature Conservancy

Victoria Dearborn is passionate about the role of nature in the lives of urban residents, from fostering a sense of childlike wonder to protecting vulnerable community members from extreme heat. As Program Specialist with The Nature Conservancy’s New York Cities Team, Victoria offers operational support and thought leadership to urban forestry projects. She helps convene the Forest for All NYC coalition, a group of 130+ organizations working to expand the NYC urban forest.

Kirk Gordon

Associate, SCAPE

Kirk Gordon is a landscape architect and Associate at SCAPE Landscape Architecture. Informed by experiences in biological research and graphic design, Kirk is committed to using design as a tool for communicating socio-ecological dynamics in a changing world. His approach prioritizes ecological vibrancy as the foundation for creating functional, resilient, and socially-engaging landscapes.

Kevin Kim

Designer, Nelson Byrd Woltz

Kevin is a designer at Nelson Byrd Woltz and joined in 2021. His previous and ongoing work in community development and public service foreground his commitment to fostering projects that progress the social and environmental resiliencies of communities impacted by climate and urbanizing shifts.

Harsh Shah

Urban Designer, AECOM

Harsh Shah is driven by a passion for public spaces, ecologies, and climate-adaptive infrastructures. His work focuses at the intersection of built environment, public realm, and urban systems, where he integrates community insights with geospatial analytics to develop impactful strategies. At AECOM, he is engaged in consulting projects for New York City’s agencies, tackling urban challenges with design innovation. A runner and ardent composter, Harsh also volunteers with GrowNYC.

Haley (Lee) Stark

Creative Director

Lee Stark is a creative director with a passion for biodiverse communities, equitable nature access, and ecosystem preservation. With a background in composting and horticulture, Lee provides creative services for organizations involved with ecology, waste reduction, circular economies, public greenspaces, and more. Lee currently serves on the Brooklyn Solid Waste Advisory Board (BkSWAB), is a Master Composter, and is a passionate steward of our local ecosystems.

John Surico

Journalist & Researcher, Center for an Urban Future

John Surico is a journalist, educator and researcher focused on mobility and open space. His reporting can be found in The New York Times, New York Magazine, Bloomberg CityLab, and elsewhere. He is Senior Fellow for Climate and Opportunity at Center for an Urban Future, where he researches parks, open spaces, and the built environment. He writes Streetbeat, a monthly newsletter on cities and how they’re changing.

Somto Uyanna

Senior Consultant, Buro Happold

Somto Uyanna is a Senior Water Infrastructure and Climate Resilience Consultant on the Buro Happold Cities team. Her professional experience includes integrated water resources management, stormwater and flood risk mitigation, environmental justice, and climate risk assessment and adaptation planning. She is passionate about improving quality of life through the built environment. Away from work, she enjoys reading, writing and editing.

1 “Biodiversity and Species Conservation,” New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, accessed August 1, 2024, https://dec.ny.gov/nature/animals-fish-plants/biodiversity-species-conservation.

2″Resilient NYC Partners,” New York City Department of Environmental Protection, accessed August 1, 2024, https://www.nyc.gov/site/dep/whats-new/resilient-nyc-partners.page.

3 “Biodiversity: Earth’s Million-Piece Puzzle,” Rainforest Action Network, accessed August 1, 2024, https://www.ran.org/issue/biodiversity-earths-million-piece-puzzle/?gad_source=1.

4 “Biodiversity and Health,” World Health Organization, accessed August 1, 2024, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/biodiversity-and-health.

5 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, A Research Agenda for the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Roadmap for the Next Phase of Research, 2021, accessed August 1, 2024, https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/26618/chapter/1.

6 NYS Climate Justice Working Group, Disadvantaged Communities Fact Sheet, https://climate.ny.gov/-/media/Project/Climate/Files/Disadvantaged-Communities-Criteria/LMI-daccriteria-fs-1-v2_acc.pdf.