In 2000, The Economist called Africa the “hopeless continent,” citing political insecurity and international indifference. One year later, African scholar Simone Abdul wrote, ”It is clear that African cities… are nowhere close to being world cities. Rather, they are largely sites of intensifying and broadening impoverishment and rampant informality.” And yet ten years later, The Economist changed its tune, reflecting its newfound optimism in a cover article titled “Africa Rising.”

It was with this sense of extraordinary opportunity that urbanists, investors, and politicians met at the end of May for The Economist Future Cities conference to explore possibilities around the exponential growth of Africa’s urban areas and the untapped potential of their largely youthful population. But what is remarkable about contemporary discourse on Africa is not the overwhelming potential of its emerging economy, but the widening dichotomy between the glossy vision of Africa’s future and the informality that defines its urban reality.

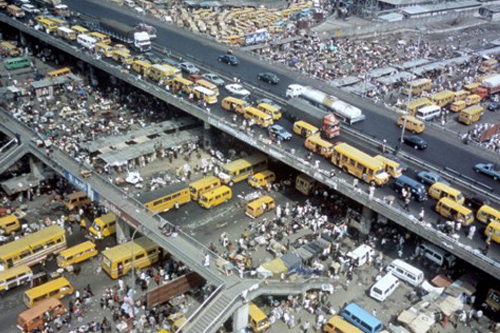

Held in Lagos, sub-Saharan Africa’s largest and fastest growing urban area, the conference convened mayors, financiers, and developers to discuss perspectives and case studies from around the continent. Lagos Governor Babatunde Fashola was among the keynote speakers discussing the colossal challenge of planning for cities of not just 10 or 15 million, but 40 or 45 million inhabitants. In the case of Lagos, infrastructure built during the modern planning movements of the 1970s has long since been appropriated by her residents; every inch of space has been overrun by congestion, slums, and informal markets. In the meantime, post-independence military leaders and politicians have fed Africans on a diet of unfulfilled promises. This has led skeptical investors to ask: how are cities with a sporadic history of planning, little faith in regulation, and no track record of implementation going to ‘leapfrog’ to design at a scale few other cities have ever seen?

Yet at the same time, with Western economies in flux, investors are looking for new opportunities, and African cities are ripe for development. Master-planned development by the private sector (executed largely outside of strategic city plans) is embraced, as in the case of Nairobi’s Tatu City or Lagos’s Eko Atlantic projects. Existing frameworks of land ownership are too confused and utilities too unreliable for in-situ development. These megaprojects come with all the trappings of contemporary urban design: high-tech business districts, luxury shopping malls, private promenades, and endless condominium towers. Their renderings reinforce a global standard (and market-proven tactics) where the objective is to create a commercial product. This type of satellite utopia aims for a kind of autonomy that will isolate residents from the perceived ‘chaos’ and dysfunction of African cities.

It remains to be seen if investors will be wooed by presentations like Eko Atlantic, where 9 square kilometers of land has been reclaimed from the Gulf of Guinea and sculpted into development parcels. Eko Atlantic suggests that it is more viable to build a massive piece of land off the coast of Lagos (dredging 10,000 m3 of sand daily and dwarfing similar instances in Dubai) than to intervene in existing physical economies.

Beyond environmental concerns, critics doubt the virtues of an imported urban form, out of context and vacant of process. These projects undoubtedly stand to bring significant economic development, but fail to capitalize on any kind of African character and starkly contrast with the contemporary manifestation of Africa’s physical machinery. The “right to the city” becomes an increasingly pertinent question when massive developments like these are rendered exclusive while congestion and services for low-income workers continue to worsen. Without taking a real lesson from history in the west, Eko Atlantic is a kind of ultimate postmodern experiment–an idealized replica of Manhattan, London or Hong Kong.

Facing the challenge of housing urban migrants, many would agree with UN-Habitat Project Director Alioune Badine that “government should not be in the business of building houses,” a lesson taken from the failure of socialist housing projects during post-independence dictatorships. It is the absence of a top-down systemic approach to infrastructure that has generated the adaptive ‘self-organization’ widely studied by writers like Rem Koolhaas, Mike Davis and Robert Neuwirth, who have identified the informal networks that exist in cities across the globe, from Rio to Mumbai.

Cultural journalist Robert Neuwirth joined the conversation to share his anthropological perspective on the power of the informal in urban life. He observed that some have tried to capture the ‘unofficial’ processes that govern contemporary urbanism in Africa, like Johannesburg mayor Parks Tau, who recently introduced a registration and regulation process for informal vendors. Neuwirth argued that because these transactions are a large portion of the global economy (an estimated $10 trillion a year worldwide), they should be integrated and accepted into the urban fabric. Others would disagree, inferring that African society–where relationships and histories are largely oral–are held up by these billions of personal interactions that cannot be cleanly translated into formal regulatory processes

Africa’s mayors in cities like Cape Town, Harare, Dar-es-Salaam, Johannesburg, and Lagos are most in touch with these aspects of city life and are becoming increasingly savvy to sustainable planning principles like nodal development, transit corridors, green space planning, and mixed use. Cape Town mayor Patricia de Lille has been working to use architecture and design to bridge social and economic divides in a community with a deep-rooted history of spatial segregation. Lagos governor Fashola presented a tree planting initiative that he hopes will leverage action from individuals to plant trees in their own neighborhoods. These mayors are keenly aware of the power of urban regulation to support a shared and equitable future – a future that is ultimately defined by the mass of its citizens. While their approach is aimed at change through integration with history, culture, and context, it is in opposition to the commercially driven mainstream that seeks to import and detach.

And while the Governor of Lagos claims to endorse a culture of planning, the new Eko Atlantic development is incompatible with most city and environmental regulations. And yet no matter how formal the project may seem, it will not be exempt from the informal processes that characterize the Nigerian city. Eko Altantic will change Lagos, but it is the way that Lagos will change proposed enclaves like Eko Atlantic that may define the future of African cities. The lesson may be what Koolhaas observed during his research on Lagos – when contemporary infrastructures are used in creative and productive ways, largely unintended by the designer.

We should welcome Eko Atlantic as a tabula rasa, and watch as it begins to accept the realities f its context–hybridizing tradition, ceremony, and an informal economy with novelty. It should forget that it is trying to keep up with New York and do its best to keep up with Lagos.