The Urban Design Forum’s 2018 Forefront Fellowship, Shelter for All, addressed the homelessness crisis in New York City by examining how to dignify the shelter system through better design and exploring the root causes of homelessness and housing precarity. Fellows developed original design and policy proposals on how to address the prison-to-shelter pipeline, public bathrooms, public realm management, supportive housing, and racist housing policies, which we are pleased to publish alongside interviews with leading experts.

Read interviews with Chris Burbank, Gia Biagi, and Paul Lotter to accompany this proposal, and view the full compilation of Shelter for All proposals and interviews here.

By Margaret Jankowsky, Stella Kim and Madison Loew

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” – Jane Jacobs

I. Introduction

New York City’s open spaces should be for everyone. The City’s open spaces should protect the dignity and human rights of people experiencing homelessness; connect those living on the streets with the resources they need; and welcome them without excluding other New Yorkers.

New York City needs to restructure the management of the public realm. By focusing on the needs of people experiencing homelessness in New York City’s open spaces, we can improve those spaces for all New Yorkers. While an improved public realm cannot solve homelessness (Picture the Homeless), it can positively impact the experiences of those who live their lives in public.

What is the public realm?

New York City’s public realm is the publicly accessible physical space between buildings – the streets, parks, plazas, and other open spaces that are open to all visitors.

New Yorkers rely on the public realm for many reasons: to move between home, work, businesses, and services; to take in light and air; to access nature, play, and recreation; to meet friends and build community; to celebrate holidays and festivals; and to engage in civic discourse and political activism. The public realm is critical to the vitality of city life.

Homelessness in the public realm today

Within the context of homelessness, the public realm serves yet another function: primary residence. Even though the number of people living on the street, in parks, or on the subways is a fraction of the number of people who live in shelters, they are the most visible aspect of homelessness for many New Yorkers, and therefore play a strong role in our collective understanding of homelessness today.

We wanted to learn, why do people live their lives in public?

The ruling of Callahan vs. Carey requires the City to provide shelter (Callahan v Carey). In order to officially qualify for shelter, individuals must undergo an evaluation to prove they have no other housing options (Main). While the City determines their eligibility, people often find themselves sleeping in the public realm (Anonymous). Before someone experiencing homelessness can be assigned a case manager, they are required to be “sighted” at least three times, at random and bedded down, by Department of Homeless Services-contracted street outreach teams (Human.NYC). If they seek shelter elsewhere in order to avoid extreme weather or temperatures, the count starts over, prolonging their application process and stay in the public realm.

Other New Yorkers experiencing homelessness choose to live in the public realm instead of in the shelter system. Shelter conditions themselves are often cited as a primary drawback: traumatic experiences with intake; safety concerns; theft from shelter residents; unhealthy or expired food, separation from support networks such as partners, friends, or pets; or a lack of accessibility (Human.NYC, Anonymous).

Apart from poor shelter conditions, a desire for autonomy and flexibility can also impact the decision to live in the public realm. Should someone choose to avoid the shelter system completely, they can still access transitional housing and services, but only after having lived nine months on the streets – a timeline subject to the same “sighting” complications mentioned above.

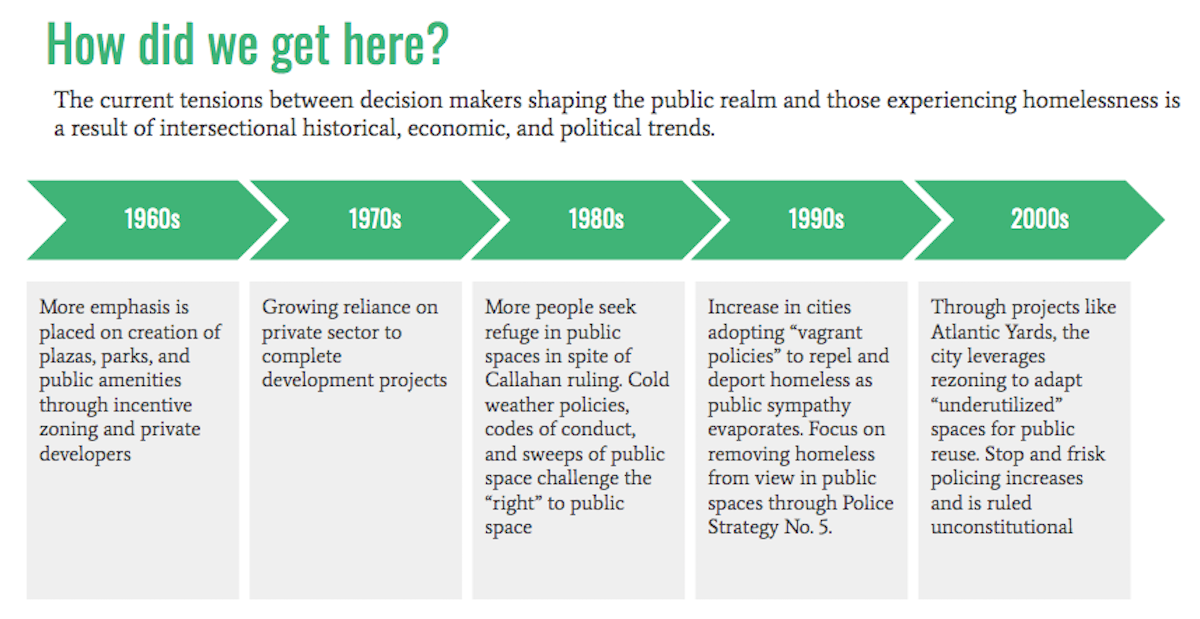

Historical context: How did we get here?

During the economic downturn of the 1970s, funding for capital improvements and maintenance within the public realm was slashed, leading many public spaces to fall into disrepair (Larson). NYC residents were also impacted by the downturn, and the most vulnerable sought shelter in the city’s streets and open spaces. In the 1980s, the city saw a growing reliance on the private sector to complete development projects and maintain the public realm (Larson).

One particular management strategy that arose in the 1980s was the creation of Business Improvement Districts (BIDs). BIDs collect self-imposed taxes from landowners within a specific area with the express goal of improving the district’s physical and economic condition. Their primary mission is to ensure the economic success of businesses within the BID, and therefore investments in the public realm are filtered through this lens. One of the first BIDs in New York City was the Grand Central Partnership, which was formed in part to rid the area around Grand Central Terminal of violence, drug use, sexual activity, and rough sleeping.

This focus on linking rough sleeping to crime in public space was officially adopted in 1994 as part of the Giuliani administration’s Police Strategy No. 5: Reclaiming Public Space, which redefined all people experiencing homelessness as “dangerous mentally ill street people” (Smith). Rather than address the larger systemic forces at work, such as deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals, stalled wages, housing discrimination, and the War on Drugs, Police Strategy No. 5 successfully appropriated the public’s concerns about urban decay and safety, directing those concerns toward people living on the streets. This enabled the City to frame the removal of people living on the street from public view–especially in high profile public spaces such as Penn Station, Grand Central Terminal, the Port Authority–as the solution to urban crime.

Sources: Giuliana Time, Building like Moses with Jacobs in Mind, City of Disorder. Download a full historical timeline here.

II. Methodology

Research methods included the following:

Primary Research: To better understand the current state of the public realm, our primary research focused on the following questions:

- What is the relationship between people experiencing homelessness and the public realm?

- What challenges do people experiencing homelessness in the public realm face?

- What kinds of improvements to the public realm can ensure the dignity of those experiencing homelessness while also benefiting all New Yorkers?

User Interviews: We partnered with Picture the Homeless to learn from people experiencing homelessness about their relationship with the public realm, interviewing in-depth five individuals who were currently or had formerly experienced homelessness.

Subject Matter Expert Interviews: We spoke with public space designers, BID and Local Development Corporation (LDC) managers, and homelessness advocates to understand the possibilities for intervention.

Media research: We analyzed articles about the homeless and the public realm to understand how the issue was being framed within the public discourse and the public’s perception of homelessness.

Era Analysis: We developed a timeline to understand historical, political, and social factors contributing to the current state of homelessness in the public realm.

Spatial Analysis: By using NYC’s open data, we mapped 311 calls regarding homelessness, public space ownership and management, and available amenities such as bathrooms.

Secondary Research Analysis: We studied existing research on homelessness in New York City, including Picture the Homeless’ 2018 report The Business of Homelessness: Financial and Human Costs of the Shelter Industrial Complex, and Human.nyc’s video interviews with New Yorkers who are currently or formerly homeless.

III. Findings

What is the relationship between people experiencing homelessness and the public realm?

People experiencing homelessness don’t encounter the public realm passively; rather, many people experiencing homelessness “live their lives in public,” according to Jacquelyn Simone at Coalition for the Homeless. Our research showed that people experiencing homelessness rely on streets and public spaces at multiple points in their journey to housing.

The public realm serves as a home and refuge for people seeking shelter, during shelter, and after shelter.

Due to the way the current New York City shelter system operates, qualifying for shelter can be a confusing and drawn out process. For example, a single adult with no history of being a domestic violence survivor would have to undergo evaluation to prove they have no other housing options. New York City Department of Homeless Services (NYC DHS) investigates the prior living situation and interviews family and friends to make sure they cannot stay with anyone they had recently stayed with. While this evaluation is happening, people could find themselves sleeping on the street. In another case, one seeking adult family shelter with their partner must provide proof of residence for the last year to show they have been homeless together for one year. During this year-long period, they also often occupy the public realm (NYC DHS).

For some, the alternatives of “safe havens,” or transitional housing options geared toward chronic street homeless individuals is more appealing than a shelter (NYC DHS). However, safe havens come with their own set of requirements.

“To be eligible for a Safe Haven (or permanent housing), a person must meet, and provide a way to prove they meet, New York City’s definition for chronic homelessness, meaning they have been homeless for nine months out of the last two years. This provides a barrier to many people who have recently become homeless or left the shelter system, leading to a wait of at least nine months before becoming eligible for transitional housing.” (Human.NYC)

According to people we interviewed who were currently or formerly experiencing homelessness, the process for gaining admittance to the shelter or safe haven system was often unclear. Being sighted in public a number of times was one way they were able to be assigned a case manager and begin the process.

“(There is a) 10-day investigation period, to find out if you’re eligible… to find out if you are actually homeless and they do the investigation. And we were found ineligible 5 times. And then finally the supervisor at Marcus Garvey Park…said… I’ll just write a letter, and I’ll explain how I saw you sleeping here and I allowed you to use the restroom to wash up, and from time to time I brought you food…So that’s when we were found eligible.” (Interview with Forefront Fellows)

“You don’t see me on the street that one night, I got to sleep on the street for a whole week just for you to put my name in the book, to put my name in a ledger.” (Interview with Forefront Fellows)

For people living in shelters, the public realm serves an important role for recreation and space to occupy – a place to go when “home” is closed for the day.

Shelters often have different operating hours, curfews, and programming spaces such as computer labs or child playrooms. During the day, residents may need to vacate their living quarters so they can be cleaned (Shelter staff interviews). As a result, many people living in shelters rely on the public realm to gather with others, or gather their thoughts. According to one person we spoke with, libraries with extended hours were a source of reprieve.

“I would go down to that library ‘cause they would stay open ‘til about maybe 11 o’clock at night, so I had extra time to use the computers and you know salvage out some of my thoughts there.” (Interview with Forefront Fellows)

Some people who have experienced shelters find living in public to be preferable.

According to Josh Dean of Human.nyc, who has collected the stories of over one hundred people sleeping on the street, many of those who choose to live on the street do so because “most of the time… the last shelter they visited caused them to feel unsafe in the shelter system.”

Some of these shelter conditions include:

- Safety concerns

- Theft from staff or other residents

- Unhealthy and/ or expired food

- Issues with service location

- Separation from supports, like a partner, friend, or service animal

- Inappropriate placements (e.g. don’t address accessibility needs)

“The worst place I’ve ever been in…[it] was just badly infested, with mice, rats, roaches, it was just disgusting. I was glad when we left, me and my partner.” (Interview with Forefront Fellows)

For some, the public realm is a platform for community.

Our conversations with people who have experienced or are currently experiencing homelessness in the public realm reveal the complex nature of ideas about “home” and its link to community and physical shelter. For some, the public realm is often the place to learn from their community about services, or places to go for food, showers, and donations.

“You gotta learn the schedules. That’s why most people be on the streets. If you ain’t got nowhere to find that routine… sometimes you gotta learn from other people on the streets… to get a meal.” (Interview with Forefront Fellows)

We also heard that the time spent on the street, subway, or parks, doesn’t end once you leave. Often, that time can become a part of your identity, or an introduction to a community. According to one man who lived on the streets for 9 years, the people he met on the street were more representative of “home” than the apartment he was provided through supportive housing.

“Just because I have a house, doesn’t mean I’m not homeless. I’m still homeless… it ain’t about having a home, it’s the people that you’re around. It’s the streets, the environment that you’re in.” (Interview with Forefront Fellows)

When asked about their relationship to the public realm, people experiencing homelessness told us about the rich community, support, and resources that they had constructed during their time there.

What challenges do people experiencing homelessness in the public realm face?

Several key areas emerged as consistent challenges for those experiencing homelessness in the public realm.

When in the public realm, people experiencing homelessness are often harassed for doing things they have a right to in public space.

In interviews with people who are currently or formerly homeless, it’s clear that they are regularly asked to move away from public space for doing the same kinds of activities that everyone else does — sitting, eating, gathering, chatting.

“They come and tell you, you’ve got to move. How’s you loitering on public property? You have a right just as anybody else. If they paying for a train ticket and you standing right there, what’s the difference between you and them? Besides they getting on a train, you ain’t got nowhere to go. You just right there in a place, that’s safe, that you can feel safe.” (Interviews)

“We’ve seen undercover cops come through with BRC…They had walkie talkies but were in plain clothes. They said, “You can’t be here, you gotta move.” (Interviews)

Public space is increasingly policed by public-private partnerships.

The tense relationship between public space and people experiencing homelessness is representative of larger issues around the increasing privatization of public space. As private interests grow in influence, public spaces are designed and managed to attract and retain a certain kind of person with spending power who could patronize a nearby establishment. As a result, the behaviors of people experiencing homelessness are questioned, challenged, and sometimes criminalized.

“Public space has always been part of being human. But that’s the challenge: What expression of humanity is acceptable?” – Jerold S. Kayden, Harvard University Graduate School of Design (Winnie Hu, “New Public Spaces Are Supposed to Be for All. The Reality Is More Complicated,” New York Tmes, Nov. 13, 2018 )

“You get overaggressive security people, some who didn’t make the police department/ shouldn’t get the police dept. They make everyone leave. They’re heavy handed with people especially with homeless. They dress a lot like police which causes confusion. They are taking away the civil rights of the people they encounter. There are all kinds of laws in place when police is doing that. When a private citizen is doing that, it is confusing and problematic.” – Chris Burbank (Interview with Forefront Fellows)

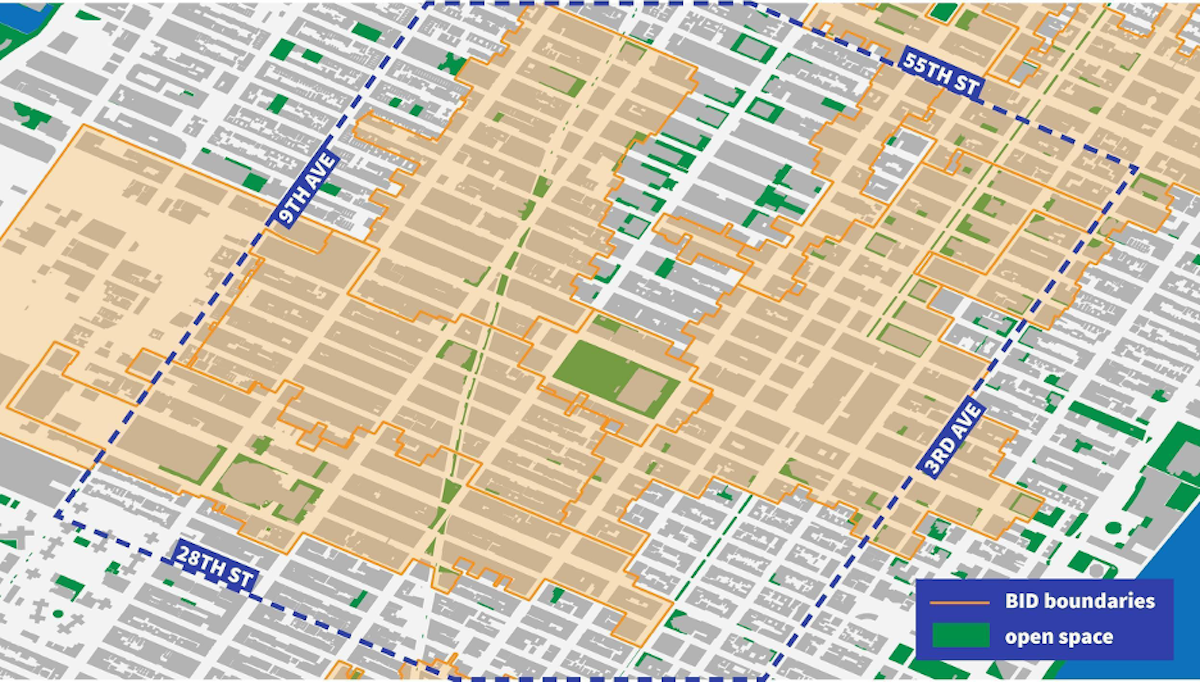

With cuts to government funding, responsibilities of managing public spaces has largely shifted to emerging hybrids like Business Improvement Districts (BIDs). Citywide, BIDs direct manage 127 public spaces (NYC Small Business Services, Business Improvement District Trends Report ‘17, pg. 34). BIDs are key gatekeepers of many New York City open spaces.

Data source: NYC Open Data.

For instance, of the 76 acres of open space in Midtown Manhattan, 68 acres fall within the management boundaries of eight different BIDs – that’s 90% of all the open space. Furthermore, some open spaces within those management boundaries – including many of the neighborhood’s signature parks, have additional management overlays, such as a nonprofit or conservancy.

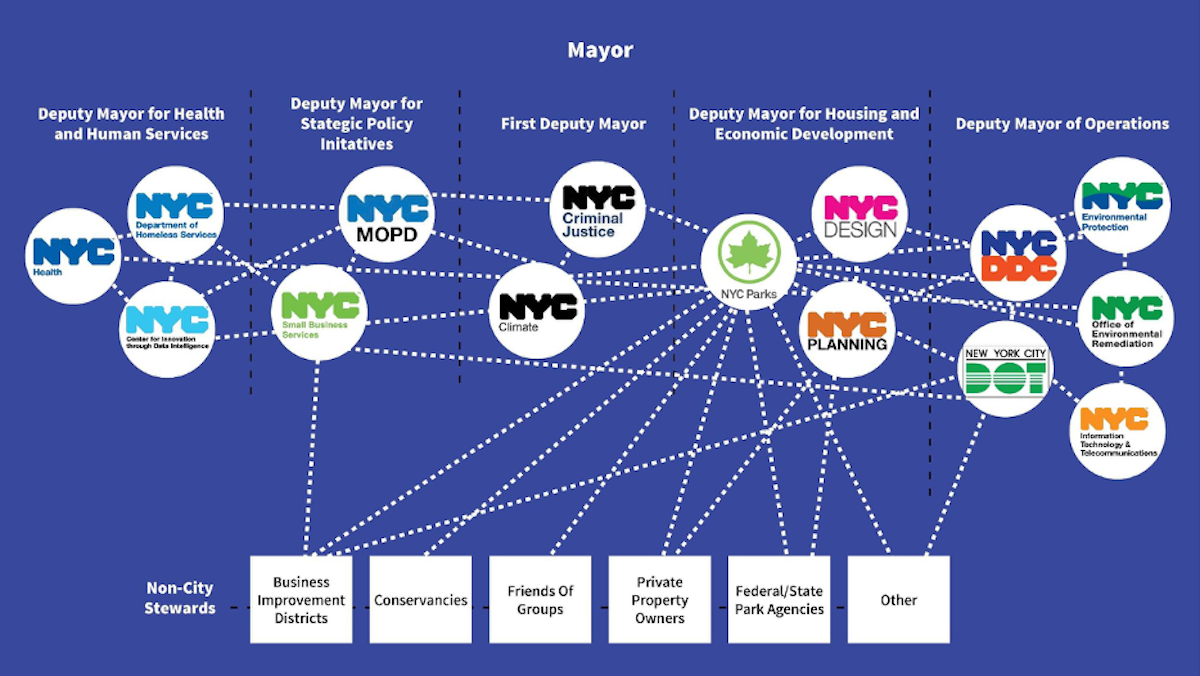

To add to the confusion, there are many different City agencies that create, manage, or oversee public spaces. Within each of those agencies, there are also different partnerships with outside organizations taking responsibility in the creation or day-to-day management of public spaces. Often, a single space is overseen, owned, or managed by at least two different entities. For example, the Department of Transportation could build a plaza in a closed portion of a street, and then partner with a local BID to oversee the day-to-day management. This web of entities may create a lack of clarity exactly who has authority over a space, what is permissible there, and who to contact if one has a concern with their rights to be in a space.

Data source: NYC Open Data.

In contrast, outside of Manhattan and downtown Brooklyn, BIDs that are less dominant retain strong connections to the surrounding community. In Ridgewood, Queens, there is only 1 BID–the Myrtle Ave BID–and only 1% of the neighborhood’s parks and plazas fall within its boundaries.

Cities across the country are increasingly criminalizing rough sleeping.

Rough sleeping and other undesirable behaviors, such as panhandling, are increasingly policed by BIDs, which represent local commercial interests trying to court a certain kind of customer, and are lightly overseen by the city government.

Image Credit: Forefront Fellows.

Across the country, municipalities are criminalizing rough sleeping. As of 2016, 88 cities passed laws or regulations that restricted sitting or lying down in public places, up from 58 cities a decade earlier (Hu). In addition, property owners and sometimes even city agencies are increasingly implementing hostile design or management practices that are often specifically aimed to discourage homeless individuals from using their public spaces. These can range from being subtle design details, such as providing narrow or backless benches that are uncomfortable to occupy for long periods of time, to more explicit actions, such as adding spikes on flat surfaces; using sprinklers to chase people away; or tasking security teams to ask only certain people to move along.

IV. Recommendations

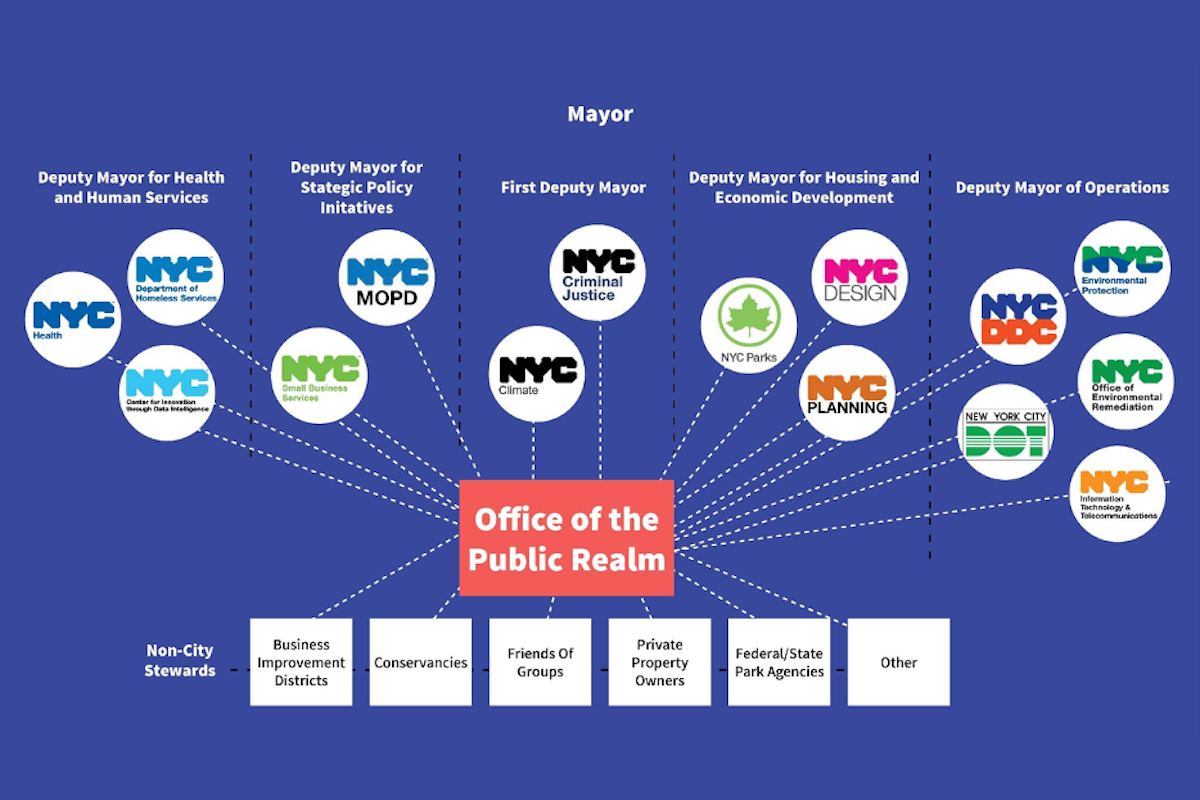

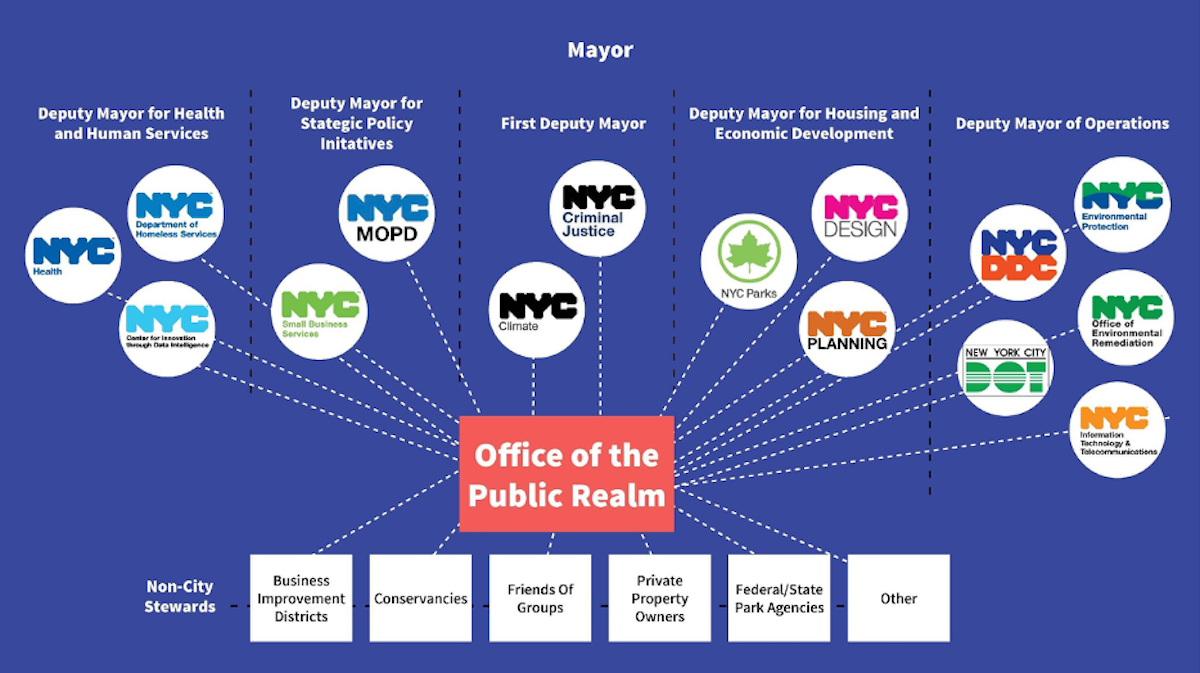

Establish a Citywide Office of the Public Realm.

The Office of the Public Realm will address the fragmented management of NYC’s open spaces, and provide a unified, clear vision for how open space will operate in the city – in regard to homelessness as well as many other municipal priorities, such as resilience and equity.

The Office of the Public Realm would be tasked with overseeing all open spaces and their managers across the city; would be responsible for providing consistent best practices and training; and would establish principles that guide the management of the city’s open spaces.

Establishing the office would centralize the City’s efforts and resources, remove agency silos, and enable better strategic planning around open spaces. Furthermore, the Office of the Public Realm could be leveraged to ensure that all the City’s open spaces are working toward larger policy initiatives, such as resilient design and equitable investment, which are often difficult to achieve within the current tangle of myriad agencies’ oversight.

The Office of the Public Realm would also benefit BIDs, nonprofits, and other open space management stewards to have a “one stop shop” with the City, to seek resources and hold contracts.

Finally, the public would benefit. They would better understand the network of open spaces available to them, expect similar ground rules and rights across spaces, and have a single go-to agency for questions and concerns.

We propose to locate this office within the First Deputy Mayor’s Office, as opposed to within one of the three core agencies that work directly in the public realm (NYC Departure of Parks and Recreation (DPR), Department of Transportation (DOT), and Department of City Planning (DCP)), in order to directly align it with the Mayor’s Office and give it a high degree of autonomy. We envision that the Commissioners from each relevant agency will have regular ongoing communication with the Office of the Public Realm. Agencies occasionally involved with public open space, such as the NYC Small Business Services (SBS), the Department of Homeless Services, the Office of Climate Policy, and others will also have direct access. In this way, the Office of the Public Realm will be a valuable internal resource for more efficient planning and oversight of the City’s open space network.

Current oversight framework of public realm.

Proposed oversight framework, with Office of the Public Realm.

The Office of the Public Realm can develop universal signage across public spaces to better communicate to the public which spaces they are welcome to use. The City should also provide information and maps for the public to clearly understand where public spaces are and what rights they have in public space. Working with experts and providers, the City should develop a public space “bill of rights”, a pamphlet for the public to better know and advocate for their own rights to public space.

The Office of the Public Realm can also ensure the public realm is accessible to all, including those experiencing homelessness. Design and management that aims to exclude certain users often creates a hostile or uncomfortable environment for everyone. Hostile design and management as described previously should be monitored, limited or prohibited.

The core agencies identified above and SBS may be able to implement these tactics more immediately than the creation of a new office, but ultimately it would be the most streamlined and coordinated, and thus more beneficial for both the City and public, to create this new office.

Require capacity building for management entities.

The negative stigma around people experiencing homelessness could be addressed if all New Yorkers better understood why people live in the streets. Those who manage public spaces and encounter homeless individuals often should be required to challenge their biases.

While the street homeless population is only a fraction of the shelter population (approximately 3,700 versus the approximately 63,500 people in shelters (DHS, data as of early 2018), these people are in the public eye and loom largely in the public consciousness. The broader public do not realize the complexities of the cycle of street to shelter to housing or the factors that have led these people to become homeless or keep them from entering shelter.

Management entities sometimes operate under stereotypes that dehumanize and marginalize these people. We interviewed a number of BID leadership and staff from a wide variety of small to large BIDs and across boroughs, and many have encountered homeless individuals in their districts or neighborhoods. Generally they found themselves in challenging, sometimes “hopeless” situations, especially with those who either sleep in the public realm or with certain behaviors that detract from the “clean and safe” mission of most BIDs. By the nature of being a BID, they also must be responsive to their Boards and business and property owners in their district.

The City should host public space stewardship training for both on-ground staff and for leadership at these organizations. Training materials should be developed in partnership with the Department of Homeless Services; formerly homeless individuals; service providers; and experts in research and advocacy. The training should cover implicit bias training; history and facts of the homeless crisis; strategies of how to navigate frequent scenarios; and a guide of city resources and contacts.

Management entities should partner with local homeless outreach and social services to better connect the street homeless with needed services.

BIDs, LDCs, conservancies and other management entities are not social service organizations. They have a primary mission of ensuring clean and safe neighborhoods and fostering commercial activity. Many do not have any social services as part of their programming, yet inevitably encounter the homeless in their district’s streets and open spaces, especially as the homeless population has increased over the years. Larger BIDs are able to hire security staff or ambassadors, while smaller BIDs’ employees monitor the districts themselves.

Many BID staff we interviewed would like to help the homeless, but are limited in resources and time to be able to take on commitments. BID staff or security officers often lack the appropriate expertise or approach to helping the homeless. Some have partnerships with service providers, NYPD neighborhood coordination officers (NCOs), and local organizations such as churches, but some exclusively rely on 311 and the police.

We propose that DHS and SBS work together to ensure that each BID is well equipped with information on accessing shelter to provide to individuals they counter. BIDs should be given a designated contact at DHS and service providers they can call. DHS has a HOME-STAT street outreach program, but BIDs do not seem well informed about how to offer resources to people experiencing homelessness in a useful and dignified way.

V. Conclusion

Given today’s highly policed and increasingly privatized public realm, we believe the City should take a more active role in protecting everyone’s right to public space through the creation of a citywide Office of the Public Realm. By doing so, the City can reclaim its stewardship of the public realm while continuing to work with existing non-profit and non-city management infrastructure, and transform fragmented management ecosystem into one that is more streamlined, efficient, and able to address systemic issues.

A truly progressive public realm starts with addressing the needs of people experiencing homelessness. The Mayor’s Office of the Public Realm will work to help people experiencing homelessness by connecting them with the resources they need before, during, and after shelter; to train public space managers and staff to be more inclusive in their approaches; and to protect the dignity and human rights of all in public. By foregrounding the most vulnerable users of public space, we can build a stronger, more just public realm for all New Yorkers.

Download Historical Timeline ►

Authors ↓

Margaret Jankowsky is Director of Marketing and Business Development at James Corner Field Operations. With a background in landscape, urban design, and architecture, Margaret’s interest lies in improving cities through their public realm. Margaret holds a B.A. and M.L.A. from the University of Pennsylvania and is currently the Director of Development at Field Operations, having previously worked on Seattle’s Central Waterfront, The Underline in Miami, and The High Line (Phaidon, 2015).

Stella Kim is fiercely dedicated to excellence in planning and the public realm. She currently works as a Senior Planner at WXY Studio, and previously managed the Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS) program at NYC Department of City Planning. Stella holds a Masters in City Planning from UC Berkeley.

Madison Leoew is a Design Manager at Nava. Trained as a service designer with a community impact lens, Madison has leveraged the design process in community wealth building projects at a state, city, and community level. She is passionate about designing equitable systems and building experiences powered and owned by the community.

References ↓

Anonymous. One on one interviews with people currently or formerly experiencing homelessness. 5 February, 2019, to 6 February, 2019.

Callahan v. Carey, No. 79-42582 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. County, Cot. 18, 1979).

Hu, Winnie. “New Public Spaces Are Supposed to Be for All. The Reality Is More Complicated.” New York TImes, Nov. 13, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/13/nyregion/public-spaces-nyc.html.

Human.NYC. New York City’s Street-to-Home Journey. https://www.human.nyc/.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Vintage Books, 1992.

Larson, Scott. “Building Like Moses with Jacobs in Mind”: Contemporary Planning in New York City. Temple University Press, 2013. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14bstz9.

Main, Thomas. Homelessness in New York City: Policymaking from Koch to de Blasio. NYU Press, 2016.

NYC Department of Homeless Services. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/dhs/shelter/families/adult-families-applying.page.

Ibid. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/dhs/outreach/street-outreach.page.

Picture the Homeless. “The Business of Homelessness.” https://picturethehomeless.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/PtH_White_paper5.pdf.

Shelter staff interviews. May-June 2018.

Smith, Neil. “Giuliani Time: The Revanchist 1990s.” Social Text, no. 57, 1998, pp. 1–20. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/466878.

Vitale, Alex. City of Disorder: How the Quality of Life Campaign Transformed New York Politics. NYU Press, 2008.

Header image credit: Forefront Fellows