Will technology change the way we move throughout the city? How should technology change the way we approach mobility?

Red Hook Link: A Proposal

Should the City Boost Private Transit Technology to Serve Red Hook?

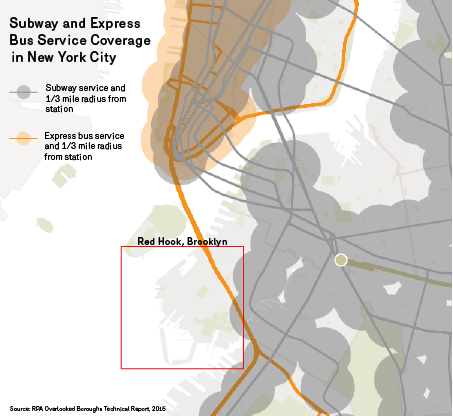

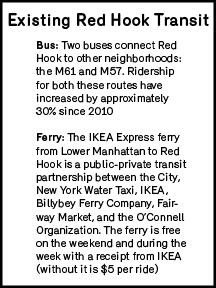

The Red Hook neighborhood in Brooklyn lacks quick access to the subway and has limited bus options. Those who live and work in Red Hook must utilize other means of accessing the neighborhood, most of which require multimodal connections. While the existing public transit options – bus and ferry – do allow people to move in and out of Red Hook, the trip time involved with these options can deter public transit use or add a significant time burden for those who have no alternative. Compounding the need for reliable, fast, and frequent transit is needed to connect Red Hook’s residential population with quality jobs; approximately 8,000 of Red Hook’s 11,000 residents live in NYCHA’s largest Brooklyn property, Red Hook Houses.

The Brooklyn and Queens waterfront has exploded with real estate development and interest in the past 10 years, with areas that have quality transit connections leading the boom. Red Hook is no exception. Since Hurricane Sandy in 2012, development has increased in the neighborhood. Proposed and underway pipeline development, including Est4te Four’s 160 Imlay (residential), Red Hook Piers (manufacturing, hotel, retail), and Thor Equities’ proposed Red Hoek Point (office and retail), demonstrate market demand and interest in Red Hook. However, existing residents and business owners continue to voice their concerns about the long-term affordability and the changing character of Red Hook as a result of growing development interest in the neighborhood. Transit access and improved mobility will only serve to fuel market interest.

The Brooklyn and Queens waterfront has exploded with real estate development and interest in the past 10 years, with areas that have quality transit connections leading the boom. Red Hook is no exception. Since Hurricane Sandy in 2012, development has increased in the neighborhood. Proposed and underway pipeline development, including Est4te Four’s 160 Imlay (residential), Red Hook Piers (manufacturing, hotel, retail), and Thor Equities’ proposed Red Hoek Point (office and retail), demonstrate market demand and interest in Red Hook. However, existing residents and business owners continue to voice their concerns about the long-term affordability and the changing character of Red Hook as a result of growing development interest in the neighborhood. Transit access and improved mobility will only serve to fuel market interest.

Political context

At face value, the mobility solution for Red Hook would be for the City and State to invest in quality public transit in the neighborhood, but the likelihood of this investment is unclear. In February 2016, Mayor de Blasio announced the Brooklyn-Queens Connector (“BQX”); a $2.5 billion streetcar that will run from Sunset Park in Brooklyn to Astoria in Queens, alternatives analyses for which are underway by EDC and DOT. If designed well, this transit investment could be transformative for Red Hook and generate economic development benefits for the surrounding real estate. The costs of streetcar construction per mile are significantly higher than the costs of high-quality bus service, raising questions about the relative mobility value of this proposed plan, but experience in other cities has shown that a permanent transit investment sends signals to real estate developers, bringing economic growth potential to the area. However, the streetcar is not slated to be completed until 2024, assuming these plans move forward and funding can be secured; unlike many capital projects financed through municipal bonds, the BQX financing strategy relies on value capture from the increased real estate property taxes of surrounding developments.

Indeed, public funding (and political will for public funding) is increasingly difficult to obtain to cover the total costs for transit investment. Although President Trump has repeatedly touted a major infrastructure investment as a key tenet of his administration, his words have so far been hollow. The Trump Administration’s recent budget blueprint proposed eliminating two of the most critical programs for transportation: the New Starts and Small Starts program (Capital Investment Grants), which matches over $2 billion in local funding for major public transit projects every year, and the popular TIGER program, which funds transportation projects in all 50 states that generate economic benefits and create jobs. Although this budget proposal is only a blueprint and likely will face opposition from Congress, it sends a strong message that the Trump Administration does not value the public investments in transit that are so critical to economically successful cities. As a result of these recent signals, which exacerbate years of federal under-investment in transportation, cities are looking to new and creative ways to both fund public transit and create new mobility options. How can cities connect people to jobs, schools, and retail in a political climate that chooses not to invest in transit projects?

Mobility technologies

In the relative vacuum of political will to invest in frequent, reliable public transit options, private mobility providers are rushing to meet demand. Some private mobility options are implemented in coordination and partnership with the city government to complement and improve existing public transportation and fill connectivity gaps, while other private sector innovations are introduced independently to capitalize on opportunities left unmet by the public transportation network.

Whether the public sector participates and partners, or not, these new technologies have emerged as a stopgap measure for mobility, continuously shaping the way people move through cities. As these technologies become more ubiquitous, they will also shape the design of cities and our approach to mobility.

Whether the public sector participates and partners, or not, these new technologies have emerged as a stopgap measure for mobility, continuously shaping the way people move through cities. As these technologies become more ubiquitous, they will also shape the design of cities and our approach to mobility.

Bike share, microtransit and autonomous vehicles are three private technologies that have and will continue to shape mobility in Red Hook. These innovations stand to be enhanced through public sector participation and supporting investment.

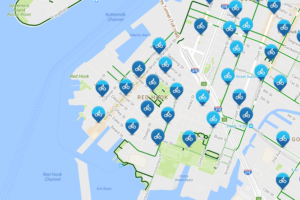

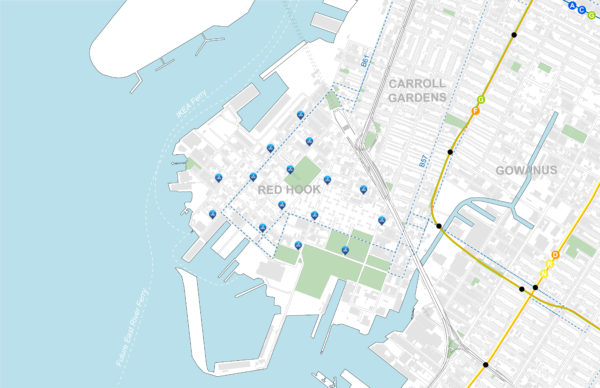

Citibike locations in Red Hook, Brooklyn (CitibikeNYC)

Bike share

Citi Bike, a public-private bike share partnership between Motivate and the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT), opened in May 2013 with 6,000 stations in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Since 2013, ridership has grown exponentially every year and an influx of new stations have expanded the service area. In August of 2016, Citi Bike added 13 stations in Red Hook, providing an additional mobility option for trips to, from, and within the neighborhood, and a convenient connection to the subway and bus lines.

Without public investment

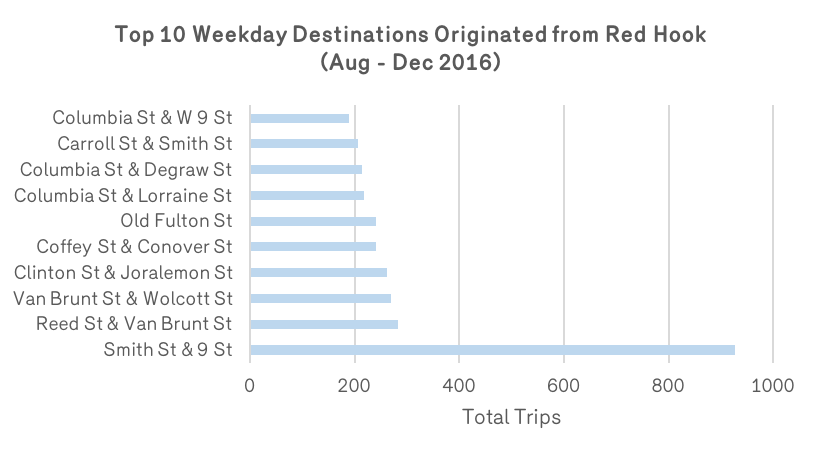

Citi Bike operates without direct public funding, though the system operator, Motivate, is contractually held to standards set by the City, providing opportunities to align incentives and goals between the public and private sector. Between August 2016 and December 2016, nearly 13,000 Citi Bike trips originated from the 13 Red Hook stations. These trips are distributed over weekdays and weekends. The top destination of Red Hook-originated weekday and weekend trips is Smith Street and 9th Street, which is adjacent to the Smith and 9th Street subway stop for the F and G lines. Weekday trips to this subway connection are three times higher than the next most frequented stop, Reed Street and Van Brunt Street, which offers a connection to the Ikea Express Ferry. These top weekday destinations in Red Hook demonstrate the usage of Citi Bike for multimodal and “last mile” connections. Weekend trips have a larger distribution of end points than weekday trips, with top destinations including other areas of Red Hook and Brooklyn Bridge Park. Even without direct City funding, Citi Bike ridership will undoubtedly continue to grow and provide a last mile connection to and from Red Hook. However, Citi Bike as an equitable mobility option and economic driver could be enhanced with additional City investment.

(Citi Bike)

With public investment

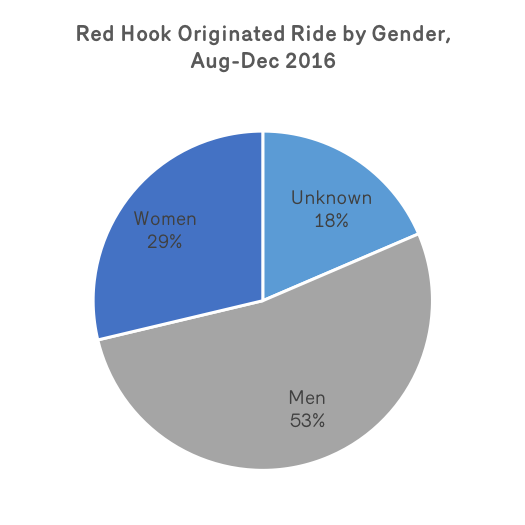

Today, there are few dedicated bike lanes that connect Red Hook to transit. Although portions of Columbia Street and Clinton Street contain bike lanes, the majority of bicyclists must share lanes with cars in an already transit-constrained area. NACTO (National Association of City Transportation Officials) found that bike ridership increases when cities provide higher-quality facilities and dedicated bike lanes. Access to bike lanes is an issue of equity in transportation: research has shown that people of color are more likely to say that they would ride more if there were protected bike lanes. Additionally, focus groups have found that women are more likely than men to “cite concerns about safety and lack of bike infrastructure as reasons not to use bike share.” Citi Bike’s user data reflect these findings; systemwide, 66% of Citi Bike users between August and December 2016 were men while 22% were women (12% of users did not identify gender). Red Hook ridership reflects a similar picture. In order to encourage biking and bike share among all demographic groups, the City should continue to invest in dedicated bicycle lanes as a way to support safe last-mile connections, as well as an environmental and healthy transit option.

(Citi Bike)

The City should also partner with community-based organizations to encourage Citi Bike ridership in Red Hook. In the Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, a trusted community-based organization (Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation) has championed Citi Bike as a way to improve health and food access. This dedicated community engagement effort has increased Citi Bike membership in the majority-Black neighborhood by 56%, and more than tripled the number of bike share trips taken in the area. A similar community-based engagement effort in Red Hook would help ensure that the neighborhood’s 8,000 NYCHA residents are aware of the available reduced-fee membership and can benefit from Citi Bike as a mobility option.

Citibikes in Red Hook, Brooklyn (The Brooklyn Paper)

Citi Bike usage, specifically its utility in making multimodal connections, demonstrates its importance and role in Red Hook. Its usage will no doubt grow over time, and could be improved and grown further with public sector investment in dedicated bike lanes that connect to nearby transit connections, and community partnerships for meaningful outreach. However, Citi Bike is not a feasible mode for all people or for all trips, and therefore Citi Bike investment alone is not a perfectly equitable solution to Red Hook’s limited mobility.

On-demand microtransit

Microtransit platforms such as Bridj and Via allow people to use an app to request on-demand shuttle service, aiming to provide the directness and convenience of a car at a cost that competes with public transit. Users can set the pick-up and drop-off location for shared point-to-point transportation, and the app’s algorithm will nudge users to the nearest corner or mutually-convenient pick-up point to reduce overall delay. Rather than the fixed route of a public bus or subway line, app-enabled microtransit routes update automatically according to demand, providing a more efficient ride. These apps, developed by private companies, can fill gaps in public transit service, providing a direct connection between two points that would require multiple transfers by bus, or shuttling people from their homes to a subway line that is just beyond walking distance.

Without public sector involvement

Microtransit can improve mobility and support first/last mile connections for those who can afford it if the market drives supply. Private-sector microtransit companies generally do not need public-sector buy-in to operate; Via already operates in New York City, though service is limited to Manhattan south of 125th Street, Williamsburg and Greenpoint in Brooklyn, and the city’s airports. It is reasonable to expect that Via service will expand to other parts of New York City including Red Hook, without public sector involvement. This and other private microtransit services will improve mobility for those who can afford it, but without government regulation, private sector providers will not be required to meet social equity goals, and these services may undermine city goals to reduce vehicle miles traveled and encourage public transit use. Though private-sector microtransit can fill an important niche where public transit is scarce, infrequent, or unreliable, microtransit platforms also have the potential to cannibalize public transit ridership and erode revenue streams for transit agencies, contributing to a vicious cycle that further degrades transit service and further discourages ridership.

Though true microtransit is distinct from app-based taxi service, lessons can be drawn from a recent report about the congestion impacts of app-based ride-hail trips in New York City. The report’s author found that services like Uber and Lyft have added 50,000 vehicles to New York City streets, and in 2016 alone added an additional 600 million miles of driving. Though microtransit has the potential to encourage shared rides, the availability of pooled options such as UberPool, LyftLine, and Via has not dampened the overall effect of an increase in vehicle miles driven.

In Red Hook specifically, app-based taxi service like Uber and Lyft, which are already available in the neighborhood, pooled rides (such as UberPool and LyftLine, which are also available) and microtransit, which has not yet reached Red Hook, can fill gaps in existing transit service or provide a convenient alternative for those who can afford it, but a proliferation of these services risks burdening the neighborhood’s streets with additional vehicles, adding to congestion and further slowing down public buses.

With public investment and participation

Public transit agencies could integrate these technologies into their services. Microtransit could have designated pick-up zones, making it more broadly known and easier to access, and reducing conflicts between shuttles picking up passengers and other traffic. Microtransit costs could be subsidized for those who otherwise cannot afford to ride and who lack access to public bus routes or subway stations, creating economic opportunities through improved access to jobs.

Taking it further, the City and the MTA could integrate private-sector innovations into public transit service and develop a pilot or public-private partnership to test microtransit in Red Hook, bringing the benefits of dynamic, on-demand microtransit in line with public sector goals of equity and accessibility. In places ranging from Kansas City to a Minneapolis suburb, transit agencies are experimenting with microtransit, using app services to provide on-demand transit in a branded, comfortable 12-passenger van. These initiatives have had varying levels of success, from over 4,000 rides a month in the Minneapolis suburb to a more limited 100 rides a month in Kansas City, demonstrating the importance of system design and marketing, as well as the importance of aligning incentives between the public sector and the private operator.

Autonomous vehicles

Today, it seems technologists, urbanists, designers, developers, and policy wonks are only talking about autonomous vehicles (AVs) and the way they will shape the design of our cities. Private companies including Google, Intel, Uber, Audi, Ford, and Tesla are doubling down on developing this technology, with beta testing occurring to-date in California, Arizona, and Pittsburgh. The question for policy makers, urban designers, and developers is no longer if but when for autonomous vehicles.

Without public sector involvement

Fleets of on-demand AVs may become the preferred mode of transportation for those who can afford them. The growth in ridesharing technology should act as an indicator that people are looking for more convenient mobility options and can adapt quickly to new options. However, like ridesharing, AVs are not a full mobility solution.

AVs may decrease the number of cars on the road, but only if they are shared. If instead AVs are for personal ownership, they may in fact increase congestion. For example, an AV may drive someone to their job, then drive on with no passengers to low-cost parking, thereby increasing parking demand and adding to road congestion.

AVs in Red Hook may decrease demand for public transit investment but should not be considered a replacement for high-capacity transit. Without equitable access or pricing, and given development proposals along the waterfront in Red Hook, autonomous vehicles may only serve to increase socioeconomic segregation in the community, with those living and working along the waterfront not utilizing public transit or supporting businesses further east. Much like ridesharing, AVs will leave those who cannot afford the technology still in need of public transit solutions.

With public sector involvement

Shared, autonomous vehicles might act like on-demand micro-transit, supporting last-mile connections for all who need them. Unlike the other private-sector driven mobility options discussed in this essay, AVs will benefit most from regulation as opposed to public capital investment. Public regulation should seek to curb pollutants and traffic congestion associated with cars. Public sector policies can also help to make AVs more equitable, supporting access to AVs for those who otherwise cannot afford them for last mile connections.

The City should begin studying its preferred policy options now before the technology comes to market. If regulated properly, shared fleets of autonomous vehicles in Red Hook could create a last-mile connection to nearby subways, decrease personal car ownership, reduce parking demand in the neighborhood, and curb pollutants from cars.

What’s next?

Private sector investment in mobility technology will continue to move forward with or without public sector participation.

The public sector should play an integral role in supporting and regulating these innovations as a way to shape equitable development in Red Hook.

Without public sector involvement in transit in Red Hook, those who can afford to pay for private transit options will benefit, making Red Hook a neighborhood that is accessible only for the affluent. Public transit investments and regulations need to be coupled with policies for inclusive and resilient growth in Red Hook so that long-time residents and businesses are not priced out of the community once mobility paves the way for redevelopment and significant residential growth.

Red Hook Link: A Proposal

Traditional transit access in Red Hook, Brooklyn is limited. Alternative modes of transportation like ferries, bike and private car-share services, have become critical in how the neighborhood is accessed. Mobility issues that include unpredictability of the local public transit, as well as lack of accessibility and affordability of some of the alternatives, have also exacerbated the current sense of isolation of the neighborhood.

On weekends, visitors and local residents take advantage of the free IKEA shuttle to connect from Lower Manhattan to the pier at Van Brunt Street (Eugenia Di Girolamo)

Bus service (B61 and B57) is currently the only mass transit options in Red Hook. Local residents often complain about the unreliability of the service

Residents and visitors would benefit from seeing all modes of transit on a single platform, and making transit information more accessible is a simple, affordable way to tackle mobility challenges in Red Hook. Enabling a direct linkage between all transportation data pertaining to the neighborhood with a central public database would unlock possibilities for real time sharing of transportation choices on different platforms. The data could be shared through dedicated apps or integrated in existing interfaces, for example as a plug-in on popular apps, like Google Maps or Citymapper, and/or on local public systems, such as LinkNYC or MTA On the Go, and on private services, such as TransitScreen.

Current transit options in Red Hook, Brooklyn include buses, private ferry and shuttle services offered by the local IKEA store, and CitiBike bike share stations across the neighborhood. An planned expansion of the East River Ferry will provide additional connections to Lower Manhattan as well as other locations in South Brooklyn (Eugenia Di Girolamo)

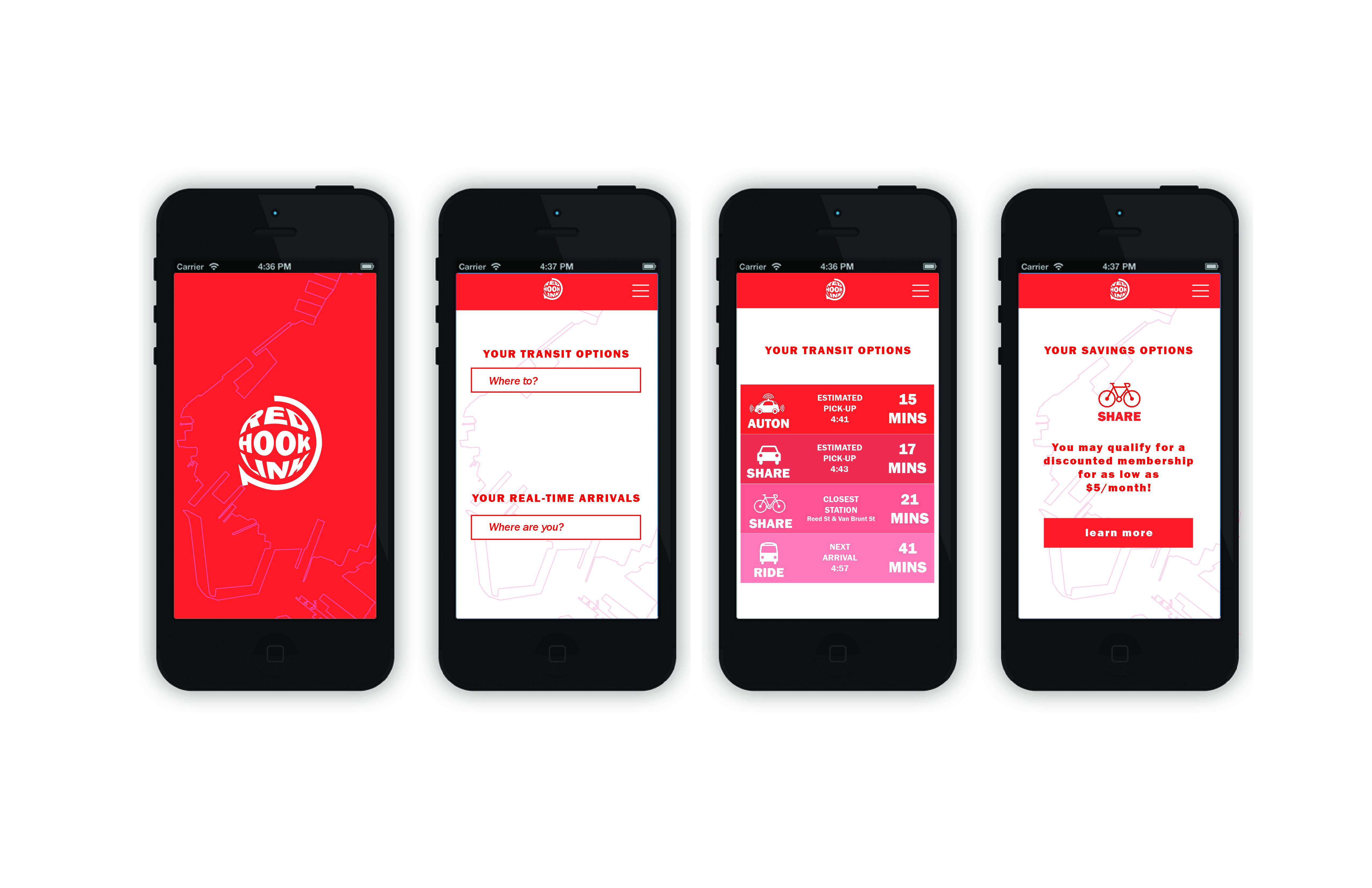

One potential implementation could be Red Hook Link, a new smart mobility app enabling better display of available transportation options in Red Hook. The Link would consolidate all options on a single platform and supply real-time arrivals as well as alternative, informal modes like on-demand micro-transit, with seemingly instantaneous capability to integrate new forms of transit as they are developed, like shared autonomous vehicles for example. Beyond transit information, Red Hook Link could also provide direct access to information related to affordability of the transportation options it displays with clear directions on how to obtain discounted fares. The app could be developed and managed by the MTA or NYCDOT, in partnership with a local BID or community organization, and funded through federal grants aimed to advance mobility on demand, like the Federal Transit Administration’s MOD Sandbox Program.

Red Hook Link could be accessed as a standalone app, as well as a physical interface similar to, or integrated with, LinkNYC. Red Hook Link kiosks could be installed throughout the neighborhood, but also at strategic locations at major points of access into the system. A system like Red Hook Link would enable a new integrated mobility experience, operating as an extension of the existing traditional transit system that could improve the everyday quality of life of the neighborhood’s visitors and, most importantly, its residents and workers.

Red Hook Link, a new smart mobility app enabling better display of available transportation options in Red Hook

Red Hook Link could be integrated into existing kiosks, like LinkNYC, and installed throughout the neighborhood to offer real time transit information to local users and enhance accessibility to and from Red Hook