Julia Day appreciates spaces where the simple joys of city life occur. As an urban designer and planner, she seeks to make better urban places, and make urban places better by bringing out the best in what already exists.

Leaving her native New York for college crystallized her appreciation for functional everyday spaces to “just be.” In places where car-centric plans left little room for walking, biking and public space, making urban spaces better beckoned as a career — one which has led her to become a Partner at Gehl. Read her full bio below.

I spoke to Julia about what good design looks and feels like; why American cities often know what would improve their designs but can’t seem to make it happen; and how designers should make the case for planning models that facilitate the everyday things that make us human.

GB: What do you do for a living? What was your journey to getting there?

Julia Day: I’m a planner and an urban designer. I work at Gehl to create cities that are more just, sustainable and healthy. My work highlights the role streets and public spaces have as vital civic assets that can influence so many parts of our day, and our life and our communities, from our physical health, to our economic stability to how socially connected we are. I work to develop partnerships with local governments, NGOs, universities, and foundations.

In terms of how I got here, I grew up in Manhattan, so I’ve been riding the subway since I was a kid. I’m still amused by how special it feels to see people in another subway car passing your subway car underground. It’s this combination of the most everyday mundane space where you’re trying to keep your head down, but also where you feel this intense human connection among strangers. And it’s in a place that might actually not be super comfortable, right? It’s dark, dirty, maybe smelly. But you get a feeling of, “Yeah, we’re all in this together,” as we’re going about our different days.

As a child, I didn’t think a lot about a profession in urban planning or design or architecture. But I knew I loved those moments where you felt this spontaneous human connection. In my senior year of university in St. Louis, Missouri, I started working as a youth voter organizer. I was going door to door, meeting with young people in schools and colleges, across St. Louis and Missouri. It was that experience of going from neighborhood to neighborhood and seeing how hard it was to get around without a car, especially for young people who didn’t have many resources. I experienced how few places there were to just be in the same space with people who are living in the same city as you. That got me thinking about urban design and urban planning. I’m sure my mom being an affordable housing developer, my uncle being an architectural engineer, and my paternal grandfather being an architect had nothing to do with it!

What does a well-designed city look like? Feel like?

JD: While there are universal design features that great places share – such as walkability, to ground floor activation to access to nature and much more – there is no one size fits all. For one, ideally the design reflects an understanding of the existing contexts of a place — its people, the various communities that are there, and the histories. At Gehl, we take a multi-method approach that involves directly engaging people and hearing from and talking to those who might not normally be engaged in a planning or design project. We also gather anonymous public life data about how people experience a place – how and where they move and stay.

A well designed city is probably also a well coordinated city – one where different government departments are aligned around the value of public spaces and the management and programming they need and work closely with civic and private partners. In the U.S., public space design and maintenance rarely fits squarely into one nice jurisdictional box. There are so many different actors involved. From the very beginning of a project, each of those actors should have a seat at the table.

In the wider urban design field, there are so many great manuals and guidebooks, like the NACTO Street Design Guide, that illustrate what great streets look like – safe, walkable, bike-friendly, transit-friendly, resilient, designed for all abilities and ages. These are open public resources. The manuals exist. But despite there being this growing understanding of what great design is, change to the built environment across the U.S. is so slow. It’s not keeping up with the needs of our residents of cities. Governance is a key part of making great design a reality.

Why is that? Where is the disconnect?

JD: Well, I’ll start on something positive. Especially following the COVID-19 pandemic, we’re seeing several cities centering public space as something key to economic recovery efforts. In places like Washington D.C., Midtown Atlanta, Reno, Nevada, and Mountain View, California, Gehl has been working on projects with city governments and public-private partners, to create plans that identify how public spaces, streets included, can be a platform to invite people back downtown.

A challenge we see often, though, is that after funding to improve street design gets secured, creative projects are implemented in a way that is so focused on function that it compromises quality of experience, and makes the invitation for use unclear.

I’ve heard two examples recently from friends and family members— both cyclists and advocates—who had bike boulevards put on their streets. One was in Brooklyn and one in Denver. And they both said the bike lanes are confusing, people don’t understand them, and they’ve been done with just white floppy bollards and paint. As a former advocate with Transportation Alternatives it feels sacrilegious to criticize any bike infrastructure that actually gets implemented. Of course, we have to do what we can with the resources our cities have, and safety is a fundamental baseline for any project. Yet when projects become just about function, we lose the quality of the experience. That might come from materiality, lighting or comfort, etc. But if we don’t help people see what the benefit is in a day-to-day way, I think it can actually hurt the cause for safer streets.

So essentially, people’s experience in a place matters.

JD: Yes. As planners, we have to really make the case that quality public space matters. Spaces where you actually feel like you want to spend time, where you want to walk, where people of all abilities, ages, backgrounds, cultures, races are safe to walk. That’s not nice to have, it’s essential.

We need quality places, where function and practicality coexist. It’s equally important to recognize the functional necessity of having public space. Public spaces are not just leisure spaces; they’re places where people are waiting to catch the bus, selling goods, transporting children, shopping, and more. There’s a real functional necessity for safer spaces, so that people can go about their day-to-day business with dignity. Not inundated with noise and traffic, or worse, fearful of traffic crashes. But we should expect more than just safety and function.

Tell me about working with the Forum as a Streets Ahead working group member, and on Neighborhoods Now. What were some of your takeaways from those programs?

JD: The opportunity to work on the ground with people across sectors and disciplines stands out. Through Streets Ahead, we went to different NYC neighborhoods to meet with local leaders, organizers and businesses working to reclaim and redesign public spaces. These visits facilitated direct dialogue where the day-to-day practitioners operating public spaces like the 34th Avenue Open Streets in Queens, often small nonprofits, BIDs, community leaders, or volunteers, could share their experiences and inform how new or adapted citywide policy and design guidance could be more relevant and tangible to how they work and what their communities and small businesses need.

As much as the field of urban design and urban planning increasingly prioritizes community engagement, it’s still often done in a way where people are asked to come and submit ideas or critique something that’s already been developed. It’s critical that the experience of the people who are the ones that policies are intended to serve have a voice in how those policies are defined.

It also spotlighted how much public space management and activation is left to local leaders and community members. To a certain degree, that makes sense, because they’re the ones that hold close trusted relationships with the communities they’re in and can help develop things that are contextually relevant. On the other hand, it’s very hard to see how that’s sustainable and equitable across all New York City neighborhoods that have such disparity of time and financial resources. Learning about those maintenance and operational challenges, too, helps to further inform how new policy or programs can help these projects be more sustainable.

Have you found any creative ways to counteract people’s aversion to change?

JD: Change is really hard—personally, professionally, universally, for all of us. I recently did the Coro Leadership New York program, and asking, “How can you get people on board to try new things?” was a recurring question. I came to appreciate that change is scary in part because, even when it benefits you, there’s some loss of what you have presently. With so much of the type of change that planners are engaging with, we’re also asking people to think about something that they maybe have never seen or experienced before. There’s a lot of unknown that comes with it.

We must acknowledge first how challenging change is, universally, and also create the space to understand why certain historical factors might exacerbate that, or why there’s a lack of trust in a process or in leadership. We have to make sure that there’s room to talk about that from a diverse range of perspectives.

Next, demonstration projects that give people something to experience, different from what they’ve seen before, are helpful. When you actually provide an opportunity to see things firsthand, to vote with their feet, then you can have a real conversation about what the change you’re proposing would actually mean. Demonstrations can start small and grow. We’ve seen temporary plazas, from Times Square to Corona, Queens, that have been so successful at demonstrating impact and importance to communities – that they’ve then gathered the funding to do permanent designs. Around the country, when so many cities let restaurants come outside and activate their streets with retail or food and beverage during the pandemic, people got to see the success of that. Now, it’s likely to become permanent.

What is something you’re excited about?

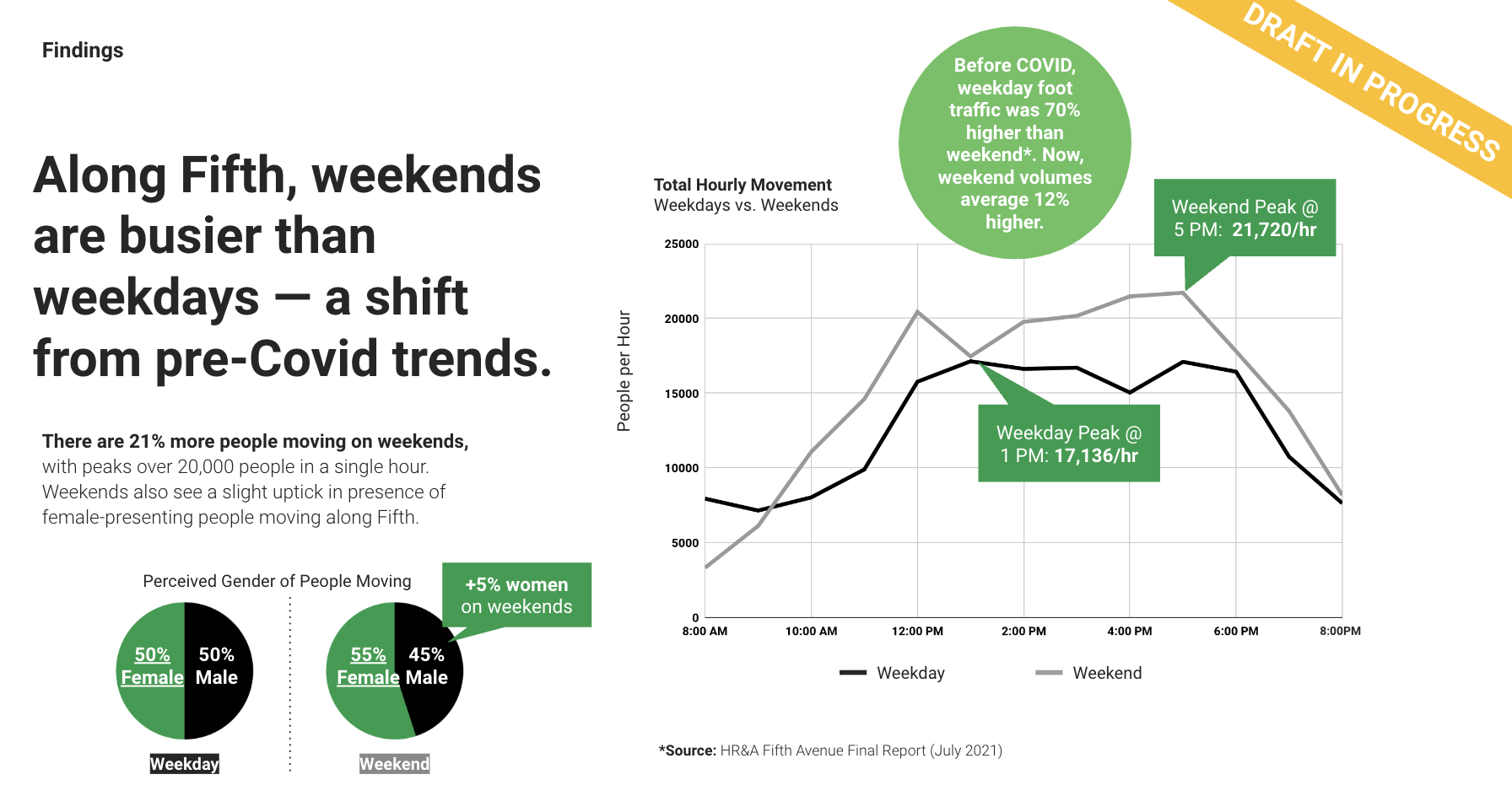

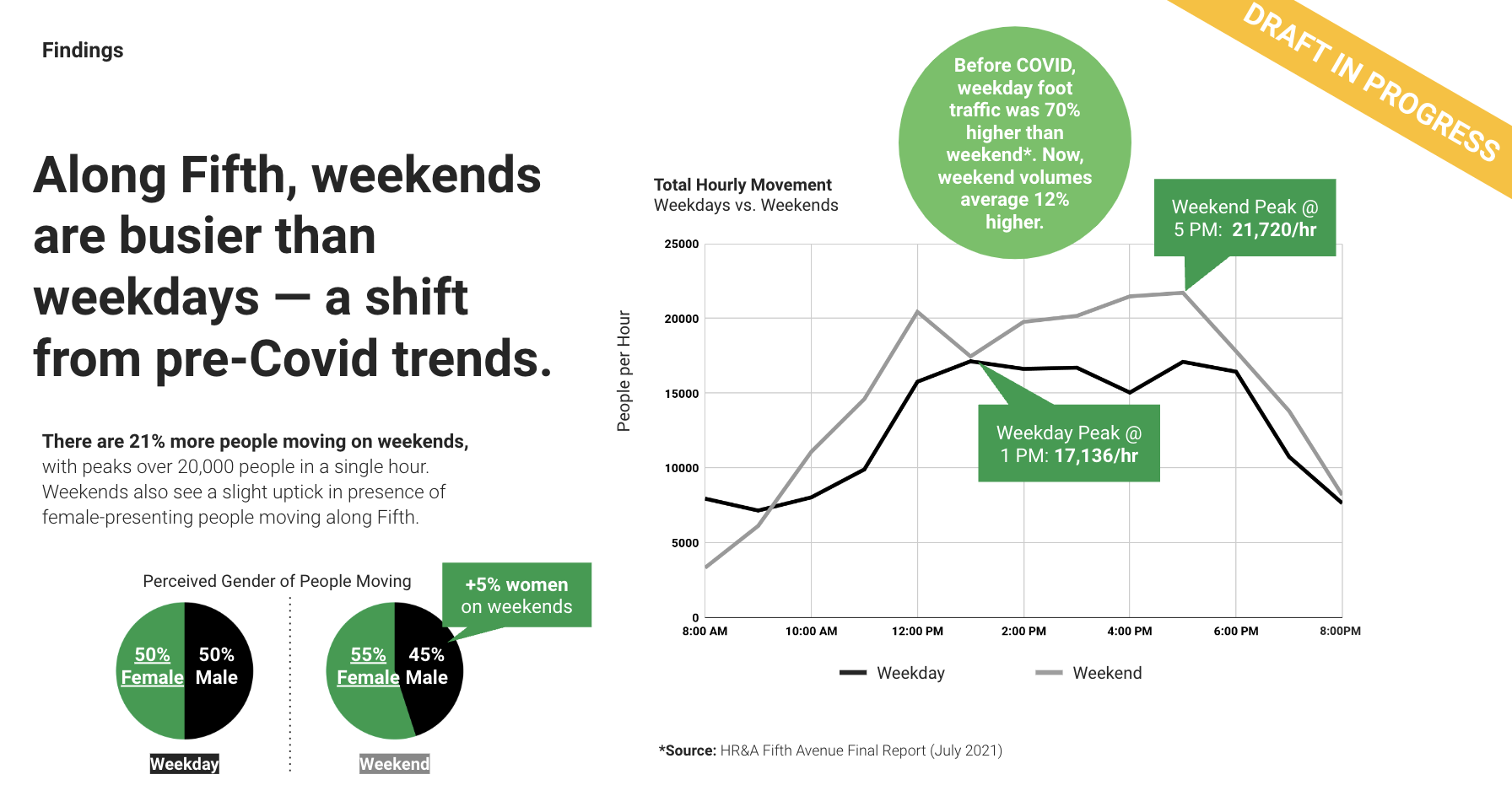

JD: We’re working on the Fifth Avenue redesign in New York City, on an incredible team led by Arcadis, Sam Schwartz, Public Works Partners, and Field Operations. We’re gathering public life data on how people experience the street today, as well as on who is there and who is not—for example, children under 15 make up less than 4% of all people observed on the street. This data will inform the new design for the street. Our hope is that we can also get some feedback from New Yorkers who aren’t there, and learn what might make this iconic stretch of Midtown a place all New Yorkers feel welcome to spend time in.

Tell me about your favorite place in New York City.

JD: That really depends on the day, the mood, the season, and the weather. I have vivid memories of entering a New York City pool, like the Kosciuszko Pool on DeKalb Avenue, on a very hot day. You’re coming off a street with very few trees, not a lot of great microclimate. And then you enter, and there’s sparkling blue water where you can find calm and cool yourself down.

In a more everyday way, I would also say the subway again. Despite its challenges, which we know are many, it’s one of those places where you do feel like you’re in it together with all these other humans. It gives you a sense of connection that’s absolutely magical.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

Top Image: Courtesy of Julia Day/Gehl.

Julia Day is a Partner and Director of the US Cities team at Gehl. Her work focuses on developing projects across design, policy and advocacy to demonstrate streets as public spaces and engage people in the planning process. Julia has worked with city agencies and community leaders in New York and London to implement Public Space Public Life studies, to repurpose streets as play spaces in communities lacking open space, to develop neighborhood design plans that support better walking and biking, and to collect new data decision makers can use to lead policy and design change in their cities. In her 9 years at Gehl, Julia has facilitated projects where urban leaders from multiple sectors can collaborate to improve quality of life. Previously, Julia worked as Director of Transportation and Health at Transportation Alternatives. In 2022, she was a member of the Coro Leadership New York annual leadership development cohort. In 2021, Julia served as a Working Group Member for Streets Ahead, Urban Design Forum’s initiative to reimagine New York’s streetscapes. Julia holds a Masters of Science in City Design and Social Science from The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).