June 15th, 2016

6:00pm - 8:00pm

Kohn Pedersen Fox

11 West 42nd Street, New York, NY, United States

Greg Lindsay is a journalist, urbanist, futurist, and speaker. He is a senior fellow of the New Cities Foundation — where he leads the Connected Mobility Initiative — a non-resident senior fellow of The Atlantic Council’s Strategic Foresight Initiative, a visiting scholar at New York University’s Rudin Center, and a senior fellow of the World Policy Institute.

Jill Morgenweck is the Director of Regional Operations at Shyp, an app-based service that can pick up, package, and ship items through a simple user interface. She holds a degree from Syracuse University in Surface Pattern Design and previously worked at Shapeways, a 3D printing marketplace. Prior to working in tech, she spent several years a competitive amateur boxer.

Makoto Okazaki is Partner and Principal Architect at Michael Sorkin Studio. Born and raised in Kobe, Japan, he has thirty years of experience in architecture, urban design, and construction management. He is devoted to both practical and theoretical projects at all scales, with a special interest in the city and green architecture.

Paul is the Zoning + GIS Lead at Envelope, as well as an adjunct professor at the NYU School of Professional Studies where he teaches Foundations of Clean Tech. Previously, he was a Senior Urban Planner at WXY architecture + urban design, where he led the New York City Green Loading Zones and Off-Street Delivery studies.

Juliette Spertus is the co-founder of ClosedLoops, a firm dedicated to developing innovative waste and freight infrastructure projects. She received her architecture degree in France and previously worked as a designer in Boston and New York. In 2010, she created the exhibit Fast Trash examining pneumatic waste collection.

On June 15, the Urban Design Forum invited Jill Morgenweck, Director of Regional Operations at Shyp; Makoto Okazaki, Partner and Principal Architect at Michael Sorkin Studio; Paul Salama, Zoning + GIS Lead at Envelope; Juliette Spertus, Co-founder of ClosedLoops; and moderator Greg Lindsay to debate the future of urban freight.

Lindsay introduced the roundtable by lamenting that freight is often forgotten in discussions of urban mobility, even though it is increasingly changing the ways we move, work, and shop. Far exceeding population growth, freight traffic is expected to increase by 70% by 2050. Lindsay called for cities to overhaul their mobility priorities and reevaluate how freight fits into our streetscapes. The evening’s presentations addressed exactly how to go about doing so.

Our first presenter, Jill Morgenweck, provided insight into one reason consumer freight is growing so rapidly: new on-demand delivery services. She works at Shyp, a start-up utilizing technology to make it easier for consumers and businesses to move goods through the city. With more individuals sending and receiving packages through the Internet, city streets are experiencing higher congestion. Unlike Amazon or other online retailers, however, Shyp picks up customers’ packages on-demand and distributes them through a third party service like FedEx or USPS. As a kind of “reverse-delivery company,” Morgenweck noted Shyp’s largest concern is the difficulty of efficient door-to-door pick-up in New York City.

With more individuals sending and receiving packages through the Internet, city streets are experiencing higher congestion.

Paul Salama addressed that concern as he presented three innovative strategies to improve urban freight developed during a study by New York State and WXY architecture + urban design. Salama called on city government to build “micro-distribution centers,” smaller and decentralized distribution buildings across New York City, similar to infrastructure employed in Paris and London to improve delivery efficiency and minimize truck traffic. These centers could be further improved with “coolpods,” small and sustainable delivery vehicles suited to navigating the urban environment without adding congestion. Packages could be loaded in distant warehouses, shipped to micro-distribution centers, and then loaded onto these vehicles before reaching their final destination.

Both proposals worked to alleviate difficulties associated with smaller-scale, Internet-enabled freight. His last concept addressed an entirely different challenge: pollution. In areas like the South Bronx, the high density of freight trucks contributes to major health concerns like high rates of asthma. By building “Green Loading Zones,” dedicated parking areas with charging stations for electric freight vehicles, Salama believes cities could incentivize delivery providers to switch to cleaner, low-impact technologies.

Salama noted a major challenge in understanding the challenges of freight: very little data has been collected about how many truck trips are made into Manhattan, what kind of vehicles comprise those trips, and how frequently freight zones are used. Another obstacle exists in the form of New York’s outdated zoning laws: freight rules were last updated in the 1950s and no longer apply to today’s high-volume delivery culture, let alone emerging technologies such as delivery drones.

Makoto Okazaki followed with a proposal to not only overhaul existing codes codes, but completely transform our model of freight movement. As part of a radical thought experiment in creating a completely self-sufficient New York City, Okazaki proposed adapting the subway system to accommodate the movement of goods. In his proposal, freight would be dispersed at night by subway to certain stations designated as distribution hubs, and then delivered locally during the early morning. Not only would this free up space for walking and parks, Okazaki argued, but city streets could be transformed into massive urban farms. This increase in production, however, would necessitate building ten new nuclear power plants, a provocation that elicited laughs from many in the audience.

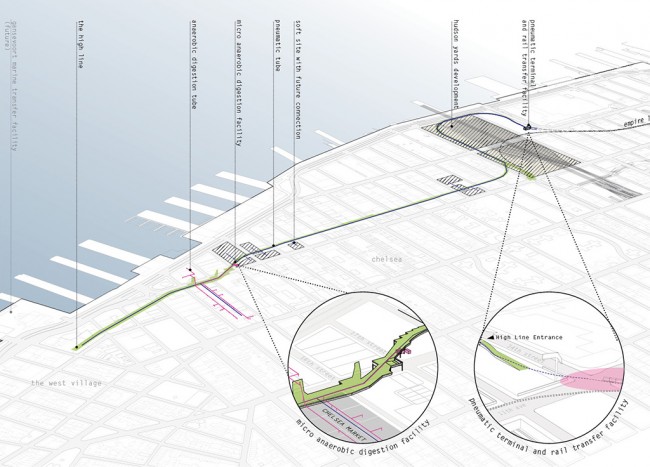

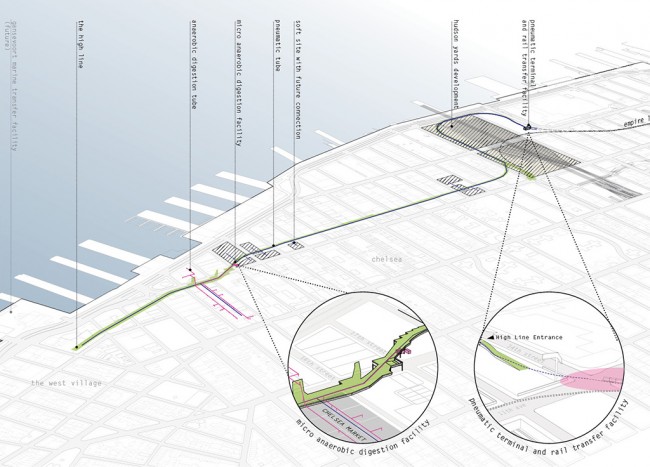

The last presenter of the night, Juliette Spertus, joked that she had considered her proposal ambitious until she heard what Okazaki had in mind. Spertus’ work is focused on waste, New York City’s largest outbound freight. She asserted we could eliminate New York’s infamous towers of sidewalk garbage while also reducing garbage truck-related congestion. Rather than send vehicles to pick up trash, Spertus envisions pneumatic tubes shuttling trash to “reverse urban distribution centers” where it would be sorted and sent to appropriate disposal centers.

New York City is already home to a functioning pneumatic system on Roosevelt Island, which Spertus noted has been expanded multiple times and even continued functioning during Superstorm Sandy. Most pneumatic systems built in the last 50 years have been in new development sites, but she sees enormous potential in retrofitting existing urban areas. Roosevelt Island’s system was originally built as a model for the city, but if Spertus has her way, the High Line could be the project that truly changes how New York deals with its trash. Its linear structure provides an ideal location to install tubes with minimal impact, and the dense development that now surrounds it provides plenty of potential waste to be diverted. Connecting just six High Line-adjacent buildings to such a system would collect as much as five times the amount of daily waste processed by the Roosevelt Island system. Additionally, food-waste from restaurants could be sorted and converted to energy on site, eliminating the need for further transport. The remaining waste could then be transferred to trains at Hudson Yards, which perhaps one day could connect to Okazaki’s freight rail system out of the city.

Some attendees questioned the potential impact of drones and autonomous vehicles in the future. Others felt solutions that accommodate more freight evade the bigger issue. “If we’re concerned about sustainable systems, we should focus on reducing the amount of goods we consume and ship,” one attendee argued. Another disagreed that our infrastructure is over capacity, suggesting that shifting the schedule of deliveries to night could ease the burden on our roads and rails.

Lindsay asked whether new technology might ultimately help or hinder local businesses. He wondered whether the on-demand economy would prove fatal to city retail, raising the specter of a city without independent shops. Alternatively, he speculated that major Internet retailers could transform the “world into a warehouse,” allowing consumers to receive deliveries from local retail rather than distribution hubs.

However, the biggest question of the night returned to Lindsay’s initial observation: how do we get people to care about freight? Many agreed on the importance of building public support for freight infrastructure improvements, but there was little consensus on how to go about doing so. But if truck traffic clogs our roads and threatens our quality of life, urbanists must rise to the challenge.