The Urban Design Forum hosted Driving It Home, the fifth event in the Shape Shift series, with two organizers confronting the nation’s housing crisis: Janne Flisrand and Tommy Newman. After the event, our Program Director Guillermo Gomez sat down with Janne Flisrand, co-founder of Neighbors for More Neighbors, a Minneapolis advocacy group that helped the city’s 2040 plan become reality. They discussed at length Minneapolis’ major citywide zoning reform, historic race-based planning policy, and strategies around advocating a fair share of housing.

Janne Flisrand, Beatrice Sibblies, and Tommy Newman at the Forum’s Driving It Home event

Guillermo Gomez: Janne, we were very grateful to hear about the incredible work you have been doing in Minneapolis around housing advocacy. I want to start off by inviting you to share a little on your background in anthropology. How did that lead you to housing activism in Minneapolis?

Janne Flisrand: Anthropology has shaped everything about how I observe the world and understand the world. In particular, it’s foundational for me that the people who experience their day to day lives have the understanding and expertise about what it is that they need. If you want to know what’s going on in somebody’s life or what their challenges are, you ask them.

I had that experience prior to becoming interested in housing when I was running a drop-in after-school program in Frogtown, a very low-income neighborhood in St. Paul. The kids were amazing, constantly teaching me things. Then, frequently a kid would stop coming. When I asked where they went, it almost always came back to housing instability. And so I thought: if I care about these kids, if I want these kids to keep teaching me, my work is making sure that they have a stable home and live in a community. I needed to shift focus not on kids but rather on housing issues.

I chose to go back to school and do an applied urban anthropology program, taking that experience in learning from those kids and understanding how to make their hopes become real in an urban environment.

GG: Through anthropology, you have been able to create a lens and methodology on how you see and practice in the city. As a housing activist in Minneapolis, what have you been able to accomplish since co-founding Neighbors for More Neighbors?

JF: Neighbors for More Neighbors was also co-founded by John Edwards and Ryan Johnson in February of 2017. They started with some humor and some jokes on Twitter and people loved it. They realized they had a following that gave them some power. Many specific housing development proposals needed a little nudge to get through the City of Minneapolis, and they asked people to show up, testify, or to send emails to support these projects. And people would do it.

Testimony on the Minneapolis 2040 Comprehensive Plan

The first successes were getting certain projects that had a bunch of housing units – apartments and homes – approved by the City. The next opening came when the City was working on its 20-year comprehensive plan. The process began late 2017 and extended through 2018. Instead of having this piecemeal, one-project-at-a-time success, we could lay the groundwork to change the system and encourage the creation of enough homes so that everybody could have one. I started organizing Neighbors for More Neighbors fans in person, turning that online interest into an advocacy group.

We activated hundreds of people to show up and support a really ambitious, comprehensive plan called Minneapolis 2040, which the City Council passed in 2019 and became effective this year.

GG: One of the reasons why your advocacy work stood out to us was your name, Neighbors for More Neighbors, and how you all have been able to communicate the benefits of a growing city. Can you share the story behind the name and how it communicates what you are all fighting for?

JF: We have a vision for a city in the future – a positive and exciting vision: our city is better when we have more neighbors.

John and Ryan, the co-founders, named Neighbors for More Neighbors as kind of a joke. They both have been active on social media – Twitter was their favorite zone – and in local politics. One day, they were sitting around, snarkily poking fun at groups that pop up any time there is a development project. These are groups of people trying to preserve their skyline views or keep their street quiet or take care of the tree in the neighborhood. As a response, [the name] Neighbors for More Neighbors was created as a way to make fun of them – and they realized it was a great name for something more.

GG: Where do you feel that positive versus negative messaging helps?

JF: Movements grow when you’re painting a picture of something that people want, when you’re able to inspire people with aspirations that connect with their values. Any movement that I’m part of is going to have that kind of positive messaging.

Now it’s also true that to motivate people, you need to have villains. But villains don’t have to be a person, right? In our case, the villain is zoning that was explicitly designed to racially and economically segregate our cities.

Now it’s also true that to motivate people, you need to have villains. But villains don’t have to be a person, right? In our case, the villain is zoning that was explicitly designed to racially and economically segregate our cities. It was designed to keep people apart. We could maybe point at the villains as the people who wrote that zoning. After the Minnesota Supreme Court made it illegal to enforce racially restrictive covenants, the City of Minneapolis came in and adopted exclusionary zoning a year later.

You need to have the bad guy but that bad guy doesn’t have to be a person. And you can’t just rely on the bad guy; you need to have something that will excite people to show up and do something.

GG: In recent years, New York City urban development has been extremely polarizing. The media or housing groups want to paint you as either YIMBY (‘yes in my backyard’) if you support growth at all costs, or NIMBY (‘not in my backyard’) if you oppose a specific development. But most of the time, it’s more complex.

What were the most successful ways you argued for more density, while building coalitions of supply-side housing advocates and others focused on racial justice?

JF: I definitely agree that this is a messy, complex set of issues and complicated set of relationships. You can paint it as two sides, but I would argue that it’s like 20 sides with arguments that aren’t opposite one another, and often are relatively unrelated to one another, although sometimes they are really closely connected.

For me, it’s always about being clear about where we want to go and our underlying values. We are focused on a city where everybody can find a place to live in the neighborhood that they choose. And it’s a place that’s stable and affordable for them. That’s our vision.

We also know that it’s critical to acknowledge and honor our racial disparities that are a result of explicit race-based policies that created an uneven playing field. And, that after decades and centuries, we’re still living with those results.

We also talk about where the actual barriers are. In Minneapolis, the most restrictively zoned places are also the wealthiest places. If we want to end displacement and gentrification, and make sure people can stay in their own communities, we can’t do that by using the same policies that we’ve used for decades. We’ve already asked neighborhoods with the lowest property values and the most historically oppressed populations to accommodate all of the growth in our city. We can’t do that anymore. It’s time for us to change our approach and say everybody has to do their share. Folks have been hosting new neighbors in historically redlined neighborhoods for decades. If they don’t want to do that anymore, that’s fine. We need to ensure that folks who have not been making space in their neighborhoods, make a lot of space right now, because they’ve got decades of catching up to do.

It is not whether you want development or you’re opposed to it; it’s about how to create a more just city.

GG: In what ways was the welcoming of more density citywide a landmark achievement for Minneapolis in coming to terms with its own racist planning history? What was your process on the ground: how did you speak about racial equity with different communities, homeowners, and elected officials?

JF: Around four or five years ago, a group called Mapping Prejudice started engaging residents to read hundreds of thousands of property deeds in Minneapolis, looking for racially restrictive covenants and then mapping them. That was really powerful because we could tell the story of how Minneapolis became racially segregated. Reading those restrictions on your computer screen and realizing that this is in your neighborhood – maybe even your own home – was a really powerful thing.

Mapping Prejudice also shared incredible stories in different episodes, where race and homeownership intersected in a way that reinforced the power, privilege, and wealth of white folks in Minneapolis to the detriment of folks who are not white. They told the story in a way that city staff could then easily frame in the housing chapter of the Minneapolis 2040 plan. They were working hard to educate elected leaders.

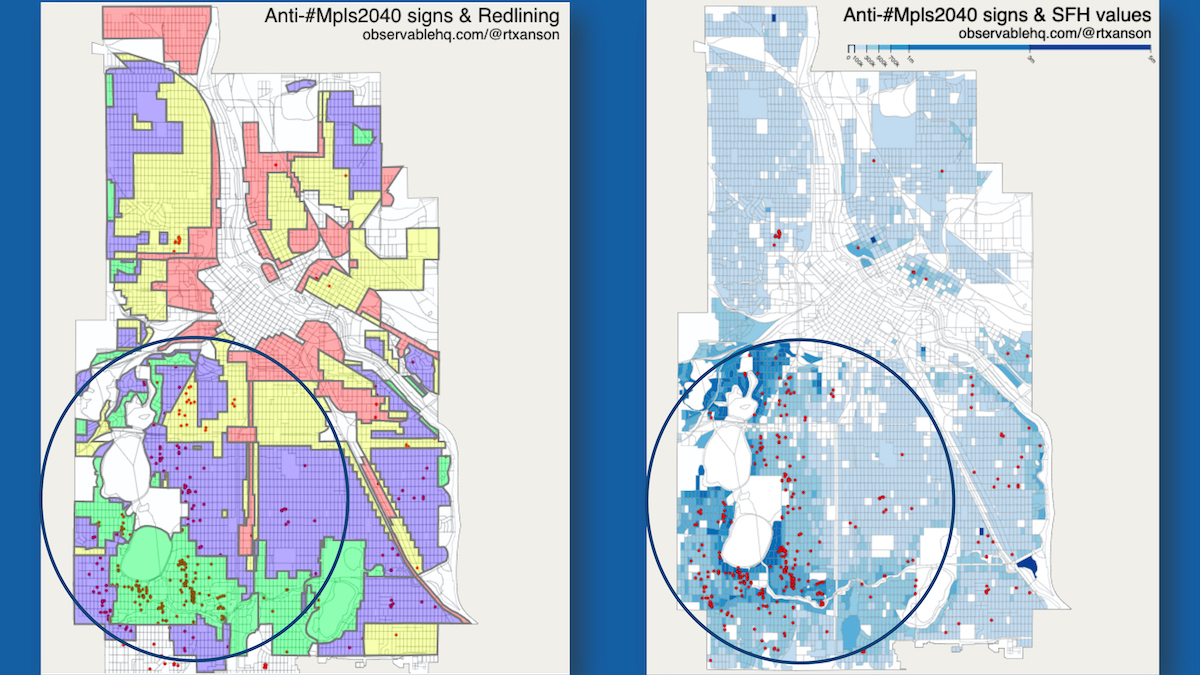

That said, not everybody was going to read the many-thousand-word introduction to the housing chapter on the comprehensive plan. Neighbors for More Neighbors took it one step further by telling that story in blogs, events and meetings. We organized volunteers to bike every single block in the city and look for the folks who are not so psyched about legalizing apartments, who put apocalyptic red signs in their yards that say things like “Developers win, Neighborhoods lose. Don’t bulldoze my home.” We then mapped those properties against redlining maps, then mapped those red sign locations against single-family home values and helped everybody see the correlation. This isn’t just a natural way of being and self-sorting and selecting. This was created by historic policy.

If we want a just future where everyone, no matter their race, can choose what neighborhood they live in, we have to tell all those stories in lots of different ways to get there. That was a really key piece of being able to pass this is plan that legalizes apartments in every corner of the city.

Redlining maps with properties opposing the 2040 plan

GG: In New York City, single-family zoning does exist, but largely in the outer boroughs. One of the challenges around housing development – both market rate and social housing development – has been resistance by homeowners under the guise of historic preservation. Have you navigated similar challenges in Minneapolis between historic preservation and greater density?

JF: Yes, we have.

Adopting exclusionary zoning to so-called “protect” neighborhoods means homes have to be expensive enough that only wealthy people can live in them. What that did was make the historic fabric of our communities illegal under the zoning code. We often say that we want to re-legalize what used to be legal in our communities. We want to ensure that the things that were legal 100 years ago are legal today, because those are the things that we love in our neighborhood. Those things create character. And right now, by saying it’s illegal to build small or even medium-sized multifamily buildings in these neighborhoods, we can’t even do what we love so much. What I love about my neighborhood are my neighbors.

What is the character of a neighborhood? Is it about the buildings or is it about the people? We land on the side of people.

Guerilla N4MN sign with local anti-development lawn sign

GG: One last question, before part. What’s the next roadblock or hurdle that Neighbors for More Neighbors is up against today?

JF: Our biggest challenge is maintaining momentum. It was clear what we were organizing around and what was needed when we were working on Minneapolis 2040. The zoning reforms that are required under Minnesota State Law, because we passed Minneapolis 2040, all have to get implemented. It’s much less clear exactly what we need to do to get all of those adopted.

Similarly, because the comprehensive plan has been adopted, how do we highlight which are the most important projects to show up for until they are completely adopted? And how do we work to make sure we’re moving further faster so that we don’t have a growing population that outstrips the new homes in our community, because that’s what pushes people out. That momentum is a little bit harder to maintain because people are really psyched about having passed the plan. They feel like we’ve done what we need to do, and it’s a little bit harder to understand what still remains.

GG: Thank you again for sharing your story with us. Often New Yorkers think they have all the answers, but I’ve come to notice over the years that New York is often far behind – and other smaller cities are taking risks and pushing for innovative design, policies, and solutions.

JF: It was a pleasure to come. I had a wonderful time. I can’t wait for New York to throw it on a challenge that then Minneapolis has to run to catch up with.

GG: You all set the bar high!

Image Credits: (Main Image) Neighbors for More Neighbors (2) Urban Design Forum (3) Neighbors for More Neighbors (4) Neighbors for More Neighbors (5) Tony Webster