As housing prices continue to rise, New York City should establish a “Development without Displacement” framework to protect its most vulnerable residents.

By Barika X. Williams

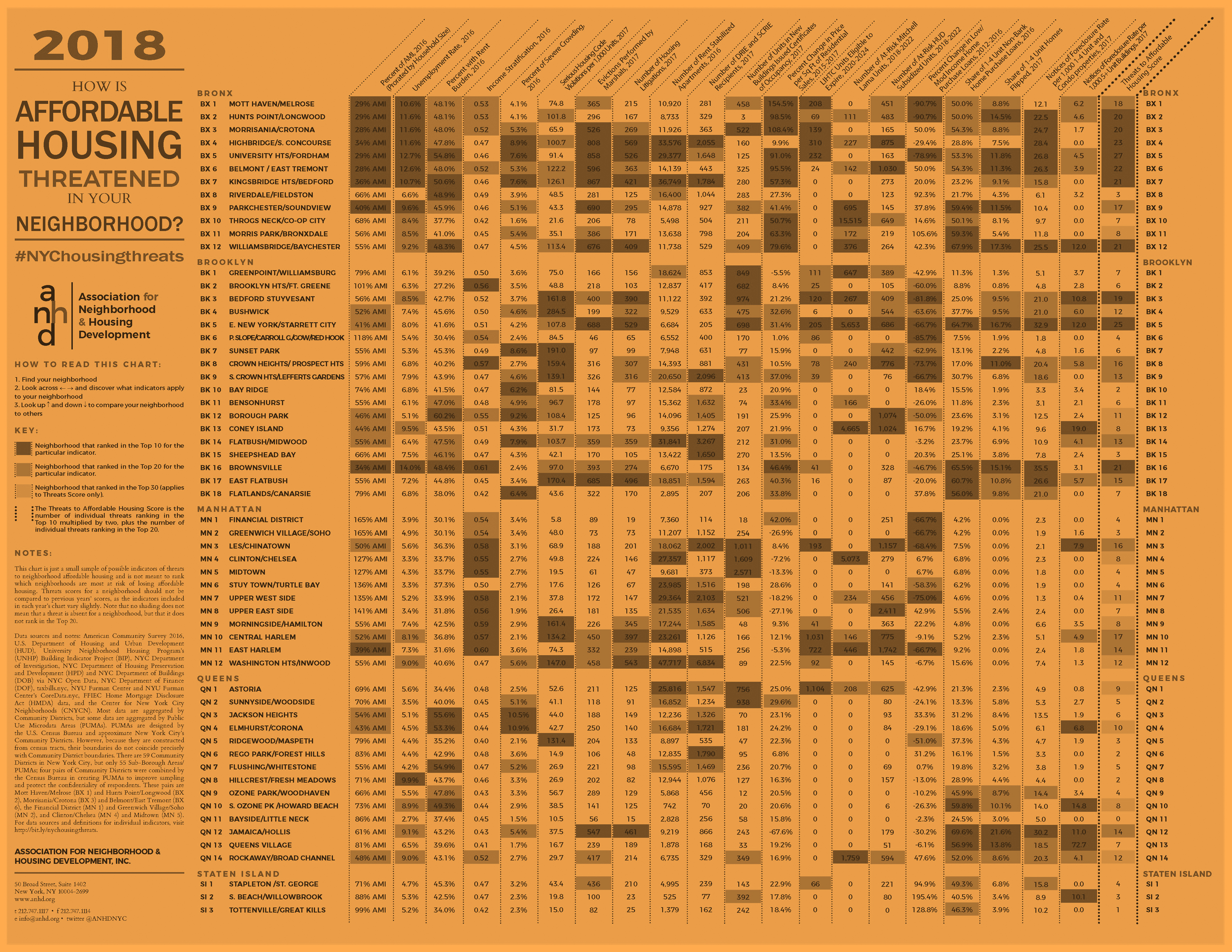

Cities across the country are struggling to address the growing threat of displacement and gentrification. In neighborhood after neighborhood, tenants, homeowners, and community groups can recount these stories, but a key challenge is the lack of quantitative data. New York City does not track when and why residents leave their homes. However, we do know that the city’s rental market is increasingly unaffordable. 1

The Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development (ANHD), proposes that New York City put in place a “Development Without Displacement” framework. This would comprise a variety of policies and programs that would accompany any new development, rezonings, or large-scale projects.

New York and cities worldwide are rapidly becoming spaces that primarily benefit those who control capital at the expense of marginalized populations such as people of color and low- to middle-income residents. For the city’s thousands of healthcare aides, childcare providers, taxi drivers, civil service employees, and minimum wage workers, the risk of displacement leaves them and their families vulnerable. We know that displacement can put households on a path of housing instability that impacts mental and physical health, employment, education, and food security—and can lead to homelessness.

The goal of the de Blasio Administration’s Housing New York 2.0 plan is to construct and preserve affordable housing. The City continues to meet its benchmarks and move forward on achieving the largest and most robust affordable housing plan in the nation. Yet, despite this massive commitment, NYC’s housing crisis persists and grows. It is time to not just set an ambitious goal, but to rethink our overall strategies and priorities. The aim of alleviating the affordability crisis for individual households is not necessarily the same as the outcomes of financing the production and preservation of affordable housing units.

We must institute a “Development without Displacement” framework to require the development of a clear and proactive plan to prevent primary and secondary residential displacement as a part of any new development. The framework would require that tools to prevent displacement be in place upfront, and applied in conjunction with all City-backed actions.

These tools would draw on recent successful housing advocacy campaigns: Right to Counsel mandates universal access to legal representation for low-income tenants when facing an eviction in Housing Court; Certificate of No Harassment ensures that building owners seeking to demolish or make significant alterations to their building prove they have not engaged in tenant harassment prior to receiving building permits; Stand for Tenant Safety was set of bills reforming the NYC Department of Buildings to prevent building construction as a form of harassment; and Housing Not Warehousing identifies vacant and warehoused properties that could become housing solutions in our neighborhoods.

These are just some of the policies fought for by housing advocates to protect tenants from harassment and displacement. But NYC also needs to put in place new tools. Every community, regardless of housing stock, should have policies and programs in place to prevent the displacement of residents. Development is not a neutral act and it can have a destabilizing impact on our communities. The city can do “Development without Displacement.” Our baseline indicator should not be the number of units, but how well we can meet New Yorkers’ needs. That ought to be the measure of a more affordable New York City.

–