Will we create a resilient city through technology? How should technology inform our response to climate change?

Resiliency And...

Can We Plan for Tomorrow with Today's Technology?

Resiliency And...

Four years ago, following the unexpected and destabilizing event that was Hurricane Sandy, our office was asked to participate in a competition called Rebuild by Design – a federal competition initiated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, geared toward finding solutions for building long-term resiliency into our cities and coastlines. As a new challenge for the U.S., we were also asked to define this very term – resiliency – what it means, what it might not mean. Implicitly, there was the notion that this had to do with climate – resiliency as a response to a climate that is changing, a way of strengthening and fortifying ourselves against a specific threat.

New York After the Storm (Iwan Baan)

On first read, this felt like a new and interesting, yet somehow specialized exercise – a new field of buoyant buildings, absorptive green spaces, and evacuation plans. As a designer coming into this, the task felt perhaps deceptively clear – the image that came to mind was of neatly conceived feats of design that allowed houses to float, or sophisticated gates that might magically transform cities into stationary urban arks.

What happened however was quite different. We were thrown into a world of aging, crumbling coastal infrastructure and highways with increasingly questionable utility; of long neglected low-income neighborhoods, and systemic distrust in government to solve local problems; of open spaces sorely lacking proper stewardship, and communities sometimes seeking to keep them that way for fear of gentrification and displacement; of dredge cycles and declining ecologies, and shifting relationships between communities and their historic surrounds.

In short, resiliency was almost the last question we came to in trying to work on the problem in an urban context.

What has been fascinating is how this one thread of resiliency touches everything in a city. The concept unlocks and is unlocked by discussions about nearly everything that shapes cities – from environment to transportation, housing and open space, governance and economics – and the way in which all these elements are intricately related to one another.

Our approach to the problem began with an idea we call “Social Infrastructure.” Like a pro-active version of the Highline, how could we piggyback upgrades to the urban realm, literally, on top of the massive investments required to raise shorelines and build resiliency into the city fabric? As designers this was a powerful possibility. But equally powerful is the way in which this piggybacking has functioned politically – in some of the most difficult environments, the need for resiliency has provided the ability to unlock multiple dimensions of city making – a form of crisis that spurs communities and governments to deal not only with climate risk but to re-think all those aspects of the city that are impacted – and to build unlikely consensus over projects and ideas that might otherwise never come close to being realized.

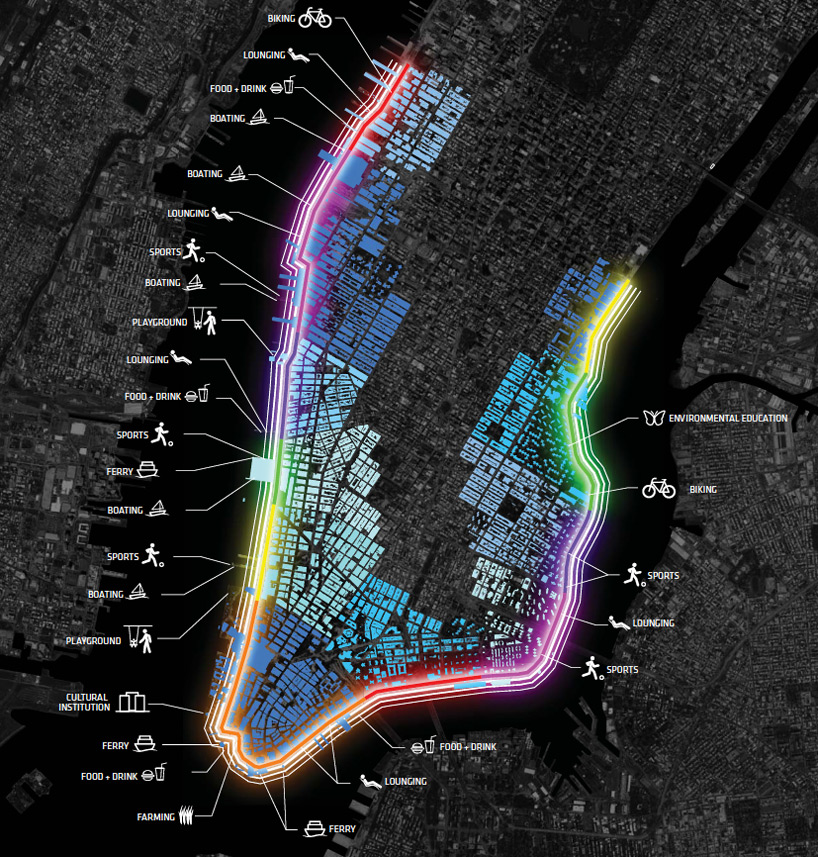

The Big U (Bjarke Ingels Group)

Upon reflection, this is of course also completely unsurprising, and would not be the first time that crisis were the source of a city’s transformation and self-reflection in multiple aspects. From the civil unrest that gave way to Haussman’s Paris, to Chicago’s Great Fire of 1871 which produced a rebuilding that generated the world’s first skyscrapers, to the demands of Cold-War defense logistics that helped generate the U.S. interstate highway system, crises have often been the instigators of broad urban change, for good or for bad, and with complex and interlocking effects.

Great Chicago Rebuilding (1872)

This year, as part of the Forefront Fellowship, we were asked to think about how our work impacts or is impacted by technological advancements – and implicitly, the climate crisis we deal with today begins with the issue of technology. It is the slowly advancing march of industry and the harnessing of fossil fuels, accelerated in the mid-19th century, which is the identified cause of an increasingly warm and polluted planet – and the point at which all registrations of a marked shift in global climate begin. The Lower East Side of Manhattan, the site for what would become the first phase of our efforts on “The Big U”, has in many ways been shaped by the very forces that now challenge it – and provides an interesting look at the way in which thinking about resiliency expands quickly into a broader exercise.

Interstate 85 Construction in North Carolina (1958)

Beginning as a coastal marshland inhabited by the Lenape Indians, the LES’s early occupation as an agricultural area slowly expanded through shoreline reclamation to accommodate countless piers serving a global maritime trade, adjacent to factories and warehouses supplying these goods, as well as a tenement district housing workers and longshoremen. It is this same industry that helped contribute to worldwide carbon emissions, and the land, built at low elevations, that is now subject to the effects of sea level rise.

As maritime trade in Manhattan declined, migrating to ex-urban areas with room for growth and horizontal space for modern containerized shipping, it was supplanted by public housing, which would slowly concentrate poor and minority communities on this low lying land, and a decade later the FDR Drive – which would accommodate vehicular flow of goods and higher-income suburban commuters back into and out of the city on a daily basis. These flows of single-passenger vehicles and high-emissions trucks would cut off access to the waterfront for those still living in the area, while further contributing to global carbon emissions. And it is these same emissions that helped generate the 13.8’ storm surge of Hurricane Sandy, overtopping the roughly 8’ elevation coastal park and neighborhood, and sending the area’s population and poorly maintained public housing stock into a sustained crisis that lasts to this day.

Smoke Over New York City, 1936 (Fairchild Aerial Survey)

Construction of East River Promenade and Park, 1938

Construction of Riis Houses and FDR Drive Expressway, 1956

The question asked of our team, and that city-builders in New York and elsewhere are now asking themselves, is what we can we do about this? As nature increasingly challenges coastal cities, it is natural systems, in fact, that we need to create to adapt to these effects. But in a city that epitomizes the conflict between different land uses for real estate, how might we actually be able to make room for these expanded forms of resiliency? If technology, in its industrial form, produced the LES’s climate challenges, can it also now provide some ways forward?

Flooded and disconnected; East River Park and FDR Drive today (Jeremy Siegel)

Technologies such as driverless cars could make huge swathes of roadway surfaces redundant – able to pack more closely together while moving, to seamlessly choreograph intersection crossings without traffic lights, and eliminating the need for parking altogether. Could this avail more space for natural areas that might handle stormwater, moderate temperature swings, and provide open spaces for a growing population? Might automated logistics and smart time-management further free up urban spaces, allowing for deliveries and waste removal to be handled on a 24-hour cycle? This could make available acres of roadways, sidewalks, and public space that today host a competition for space between pedestrians, nature, and overly sized, carbon emitting vehicles that often bring mid-day traffic to a standstill. Coastal highways like the FDR and others still encumber the city’s shorelines, relics of an era in which easy access into and out of cities was privileged over quality of life within cities themselves. As more goods production, waste processing, and living co-mingle with each other in cities, aided by cleaner, more efficient industry, can we win back space for ferry service, bike routes, housing, and other forms of transit and occupation that could further reduce our reliance on carbon? Can more efficient use of our current building stock, enabled by apps such as AirBNB or Google Spaces, reduce the amount of land area occupied by traditional hotels and office buildings, leaving it open for sustainable, non-suburban housing or natural areas? And can local manufacturing, pre-fabrication, and material advances make this re-construction quicker and more feasible?

Designing for autonomous vehicles – streets for people and nature first; Google Campus, Mountain View (Bjarke Ingels Group and Heatherwick Studio)

Through our and others work on Rebuild by Design, we have been able to inject some of this thinking into the processes of project identification and implementation as New York City plans for the future. Beginning with open space and waterfront access, we will be restoring 2.25 miles of waterfront parks on the East Side, reconnecting them to their communities with new bridges and re-introducing native and salt-tolerant ecological areas, alongside areas for active recreation and sports. Widened and enhanced bike routes will allow New Yorkers to more easily commute along the coast without needing to hail a cab, and expanded ferry service will link these routes to other coastal neighborhoods throughout the city.

In Lower Manhattan, constrained for space and encumbered by an aging FDR viaduct, the city has already begun exploring creative ways to think about bundling transportation, open space, and other neighborhood improvements to achieve multiple goals with its resiliency projects. But as with any long-range planning effort, there are challenges in matching future possibilities with the physical and political realities that exist today. While a single, forward-thinking landowner such as Google might be able to take risks and experiment at the scale of a campus, the speed of technological advancement will likely outpace that at which large cities like New York are able to incorporate these into shovel-ready public projects. This makes future flexibility an important consideration in resiliency work, and provides an additional parameter in siting, design, and phasing of improvements – from consideration of future transit, to land use, to logistics and operations, all of which will be shaped by the kinds of technological advancements being discussed today.

Multi-Purpose Levee Concept, NYC Special Initiative for Recovery and Resiliency, 2013

Today, East River Park, Delancey Street – East Side Coastal Resiliency Project (Bjarke Ingels Group)

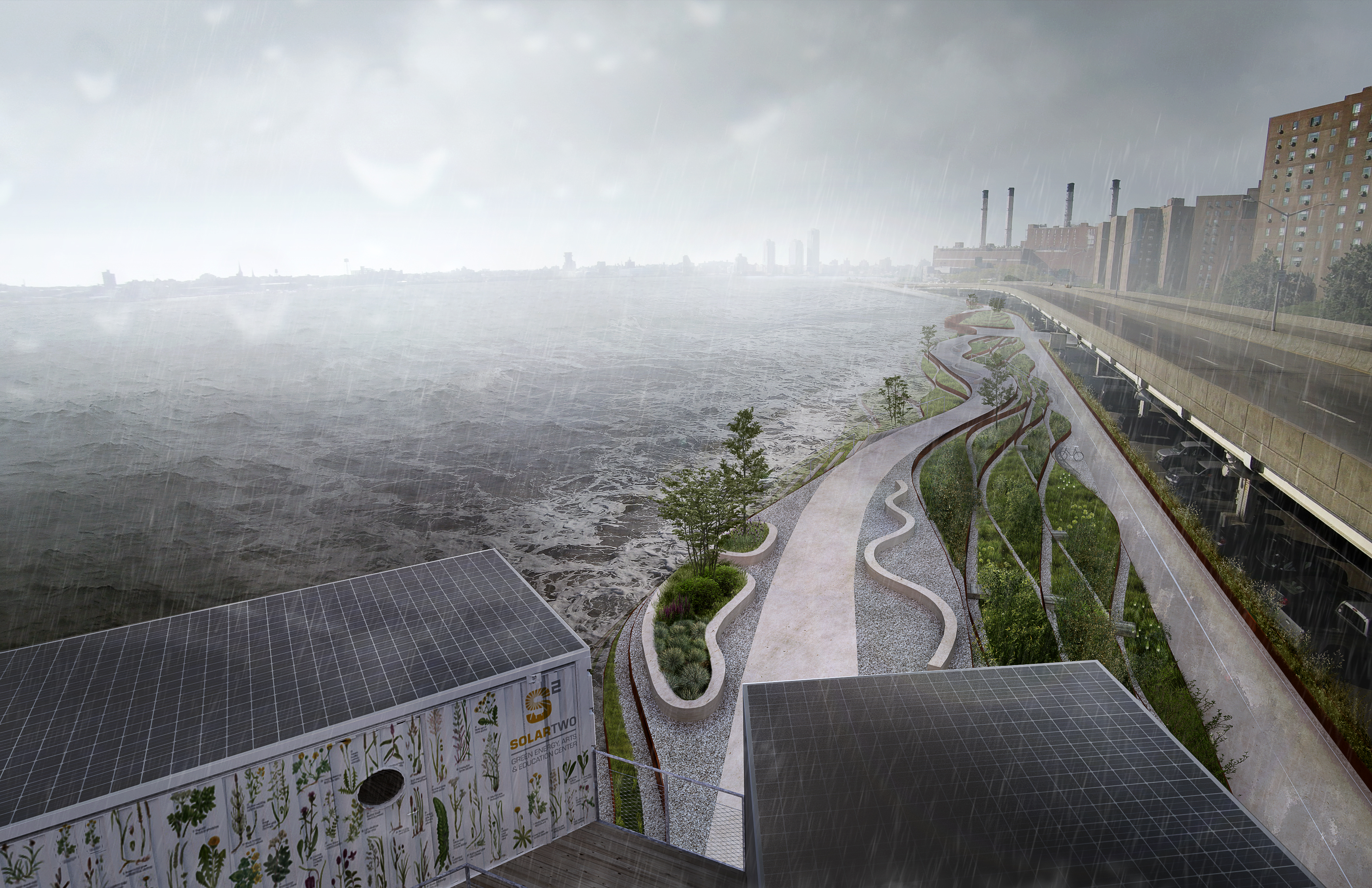

The Bridging Berm – East Side Coastal Resiliency Project (Bjarke Ingels Group)

Manhattan Greenway – East Side Coastal Resiliency Project (Bjarke Ingels Group)

Stuyvesant Cove Park – East Side Coastal Resiliency Project (Bjarke Ingels Group)

Stuyvesant Cove Park, Storm – East Side Coastal Resiliency Project (Bjarke Ingels Group)

These advances provide seductive possibilities, and many will likely aid in making New York and other coastal cities more able to reduce carbon emissions while adapting to the climate we have created for ourselves in the present. But as with any technology or development that works at scale, these will just as surely have knock-on effects that are difficult to predict – how will communities develop as turnover increases through space sharing? How will local economies react to automation of services and the loss of these jobs? What will increased interaction with machines, rather than people, do to our social fabric? The answers to these questions may be impossible to predict, but this makes it all the more important to take this moment in history to think holistically about our coastal neighborhoods and shorelines, dealing with both climate resiliency and, at the same time, all those aspects of the city that will make them more social, livable, and exciting places to be in the future – while being wary of the same forms of technophoria and myopia that have produced the very challenges we are faced with today.

Can We Plan for Tomorrow with Today's Technology?

The concept of resiliency is not limited to the physical environment; it can also be applied to social and economic systems. Maintaining a balance of all three systems is important for communities as they address the five phases of emergency management: prevention, preparedness, response, recovery and mitigation.

2017 has brought advancements in technology related to transportation infrastructure like automated and electric vehicles, ride-hailing apps, recycled and environmentally friendly construction materials, to name a few. Yet while there have been global advancements in transportation technology, certain neighborhoods within New York City are slower adopt these advancements—even if they are more commonplace in other parts of the City and in other transportation systems around the world. Without being on the cutting edge of technological invention, there are current devices and technologies that exist today can help these communities ‘catch up’, and also positively influence public transportation ridership. The transportation network of the North Shore of Staten Island– currently undergoing an economic, physical and social transformation—presents an opportunity to implement this hypothesis.

North Shore, Staten Island’s downtown

The North Shore of Staten Island (or Downtown Staten Island as it is affectionately called) is going through a period of major economic investment and neighborhood transformation. Through major private and City investment, the North Shore is seeing the construction of new mixed used buildings (Lighthouse Point), multi-unit residential complexes (URBY Staten Island), retail centers (Empire Outlets) and tourist attractions such as the New York Wheel—an observation wheel that is set to be the world’s largest. The Bay Street Corridor, a vital roadway and commercial corridor within the North Shore, is simultaneously undergoing a neighborhood planning study in an effort to reevaluate land uses, create open space, support economic vitality and construct affordable housing. While phased, this influx of development and neighborhood rezoning will impact all components of the environmental and social infrastructure.

Dilapidated pier adjacent to the North Shore right-of-way rail line. The pier was destroyed as a result of Superstorm Sandy (Tiffany-Ann Taylor)

Unfortunately Superstorm Sandy left its mark on Staten Island as it left the North Shore with the most damage and life lost within New York City. Battered shorelines and businesses being rebuilt and raised above sea level are reminders that Sandy, or far worse, can happen again. These key lessons have taught New Yorkers that with all of this development happening, now more than ever–social, environmental and economic resiliency are necessary for communities to not only survive but also to grow sustainably. A key part of this sustainability is the efficiency and diversification of the area’s transportation network.

Resiliency and Staten Island’s the North Shore’s transportation problem

It is no secret that Staten Islanders love their cars, and the North Shore is no different. There are many options within the transportation network on this part of the island as it is home to the Staten Island Railway (SIR), the St. George Ferry Terminal (the major transportation hub for the island and the main connection to Manhattan), 22 bus routes, and bike routes scattered throughout the area. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) has also examined public transit alternatives for Staten Island’s North Shore. In 2015, the MTA allocated $5 million to further study the feasibility of Bus Rapid Transit as a result. As new residents and visitors venture to Staten Island to live and patronize new developments, the pressure of new ridership demands will be put on the local transportation network and it must adapt in order to ensure the community’s resilience.

Abandoned station platform for the North Shore ROW rail line (Tiffany-Ann Taylor)

When conducting a transportation study on Staten Island and interacting with community stakeholders, I learned quickly that it is still a challenge to get North Shore residents and ferry commuters to embrace intra-island public transportation. Combined with a general aversion to increased building heights, population density and diversity in housing stock, North Shore residents are putting themselves in a vulnerable position that perpetuates a lack of affordable housing, increased commercial vacancies and disinvestment in the public transportation network. The existing infrastructure can support increased ridership and current technology can be used to encourage its use. Diversity in transportation options supports equity in transportation accessibility, spurs economic development and allows for easier evacuations prior to an event and facilitates a faster restoration to normalcy afterwards.

Using today’s technology to prepare for tomorrow

Innovations in technology happen every day. However, the distribution of these new ideas moves much slower. Local governments (county, City, State and otherwise) do not always have the luxury of constantly purchasing new technology even if it increases user experience and system efficiency. However, I will argue, that sometimes already existent technology can be implemented and make a huge impact.

During the course of my transportation study, I realized that while encouraging Staten Islanders to rethink their transportation options was a challenging task, current technologies and data exist to help increase awareness and ultimately, the efficiency of the transportation network on the North Shore. The following devices and software were found to be instrumental in bridging the conversation between economic growth and the need for diversity in transportation options, in order to accommodate both new and old visitors and residents:

- Social media campaigns that promote public transit awareness

- Create and distribute short web addresses (bit.ly/SINorthShore) to encourage passengers to participate in mobile phone friendly trip generation surveys

- Real-time passenger information signs were suggested to improve the trip planning experience

- Transit Signal Priority (hardware that can be installed on traffic signals and transit vehicles to give them priority at intersections) was recommended to improve the travel time of bus passengers

- Ride-hailing apps such as Uber and Lyft were not included as recommendations in the study but should be considered advancements in transportation technology. These businesses incentivize their carpooling features and are beginning to venture into automated vehicular travel—arguably something to consider as part of environmentally friendlier travel

Using real-time passenger information signs as an example, these devices display messages to inform passengers of the next arriving train or bus. During an event, these signs can also be used to broadcast emergency information.

Real-time information signage for Select Bus Service in New York City (AM New York)

Climate Change, future federal policy and funding

The effects of climate change mean that New York City will continue to see an increase in both frequency and severity of natural weather events. With the understanding that that the City is also an unfortunate target for manmade attacks, it becomes abundantly clear that we must be proactive and prepare for the worst. In order for Staten Islanders, and the rest of the City, to be prepared we need to make sure that our infrastructures (social, environmental and physical) are healthy, sustainable and resilient.

A diverse and redundant transportation network is a critical component to being prepared.

We are currently in the first year of a new federal administration and what will undoubtedly be the beginning of more conservative governing, policy creation and spending. At the time this piece was written, a draft of the Country’s new federal budget was been released but not yet adopted. Therefore it is unclear what programs that encourage technological innovation, support capital investments in physical infrastructure or protect our environment will be affected by budget cuts. So we may have to start thinking critically about how we can use what we already have to help us prepare for new challenges tomorrow.