Movement of people was abruptly halted due to the pandemic, especially in bustling cities like NYC where the subway and buses are essential modes of transportation. As we enter the fall, how can we plan future investments and envision alternative patterns of mobility within our city? These proposals advocate for creating robust walkway systems and restructuring traditional train platform systems to enable safer mobility.

Public Transit During Corona: Regaining the Trust of the Subway Traveler

An Analysis of Subway Ridership During the Pandemic

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Urban Design Forum launched City Life After Coronavirus, a digital program convening Fellows and international experts to document global responses to the current crisis and to strategize a road to recovery for New York City. In April, we released a Call for Ideas to our network soliciting a broad range of submissions that envision how urban planning and design should change in the wake of Covid-19 as we strive to build a more just city for all New Yorkers. We are featuring some of the most compelling ideas in a series of reflections and proposals about diverse topics like education, community engagement, and mobility. Explore the full Gallery of Urban Ideas here.

Public Transit During Corona: Regaining the Trust of the Subway Traveler

How Public Transit Will Survive the Coronavirus in Legacy Cities

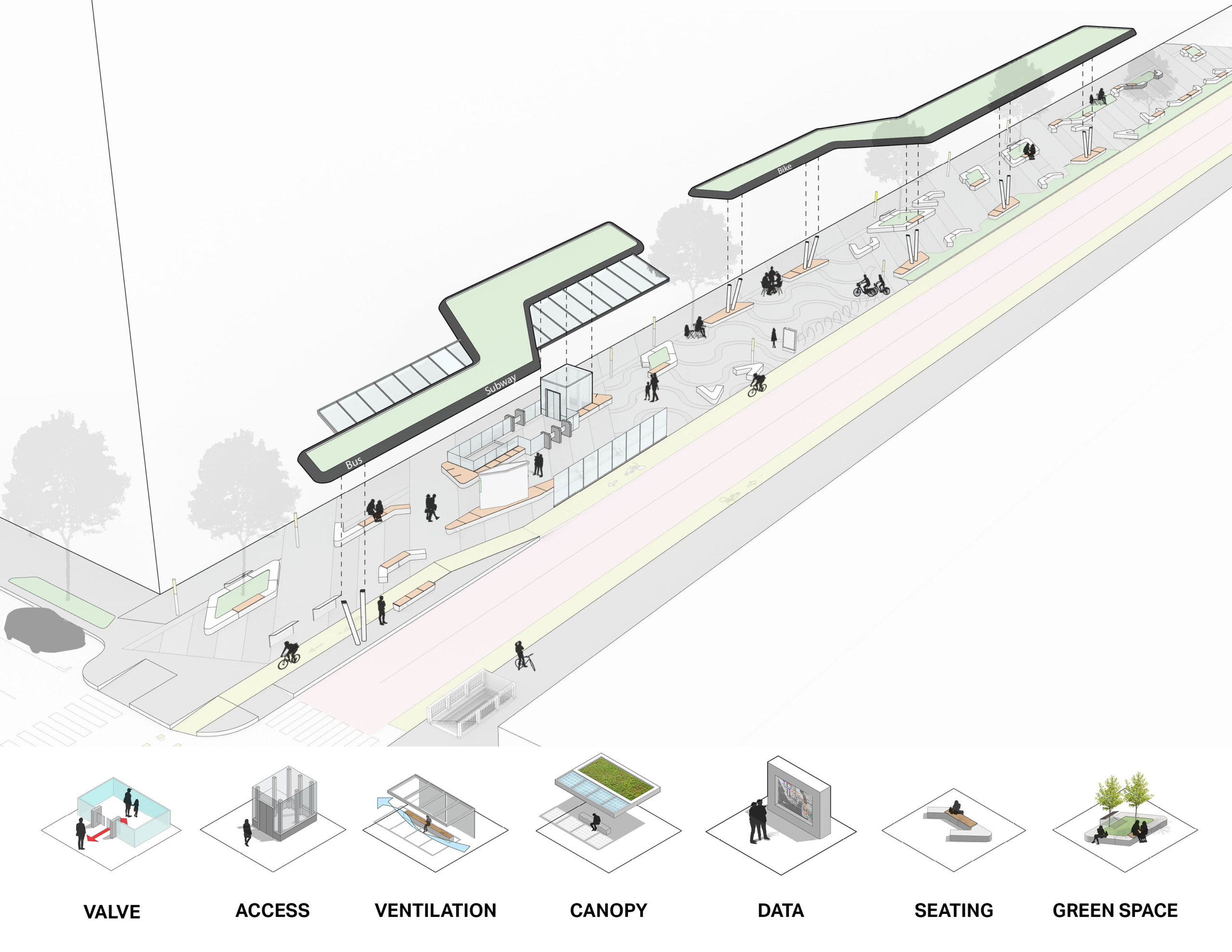

The Concept

The days of overcrowded subway platforms and trains are over. In large global cities with legacy public transit systems, like London, Paris, and New York, a populace not feeling safe when using public transit poses an existential threat to the transit system and, ominously, to the city that relies on it. But these same cities have assets that will allow them to overcome this challenge, including a vibrant public realm at street level which can be leveraged to manage the flow of people into the subway system, allowing the subway to comply with social distancing standards.

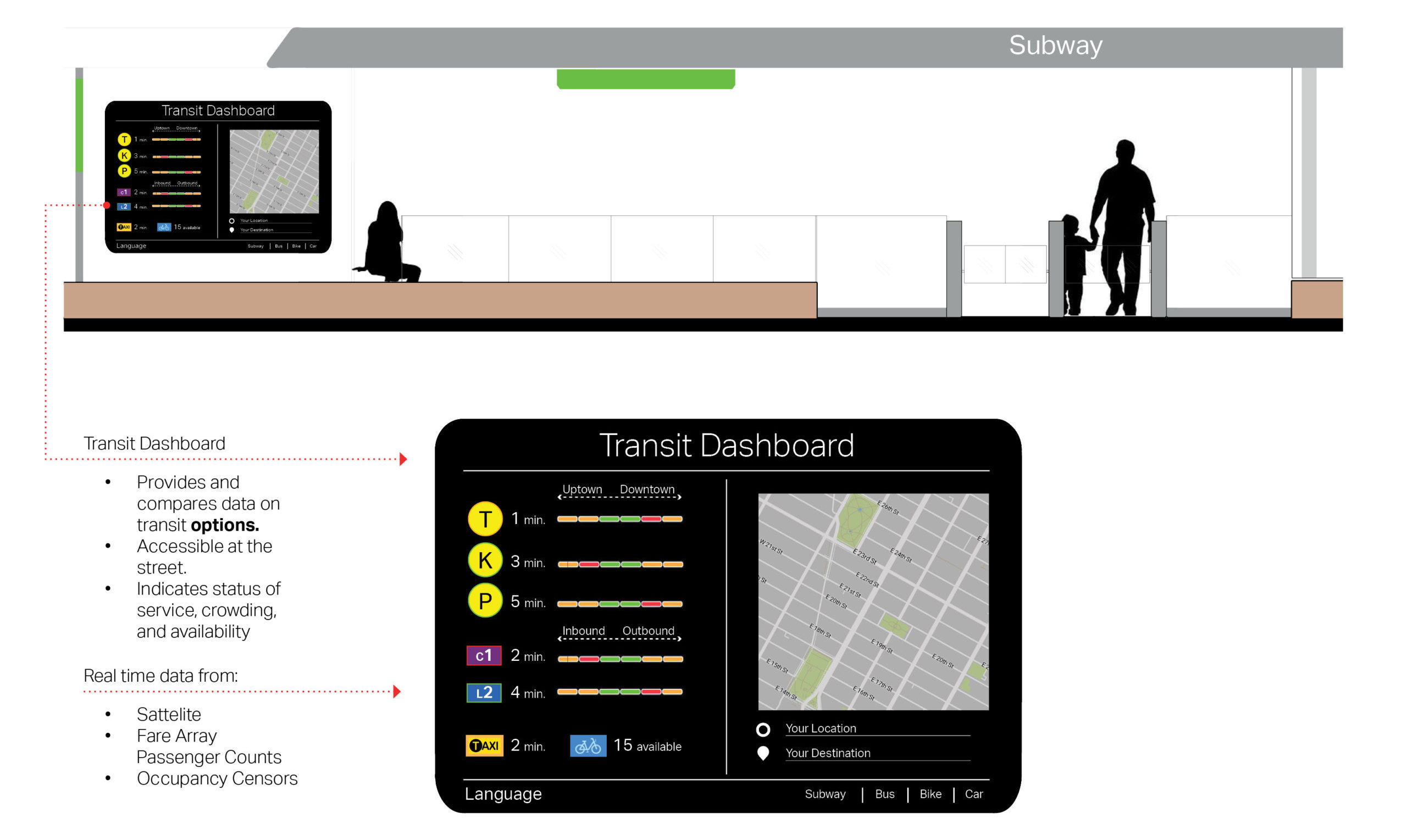

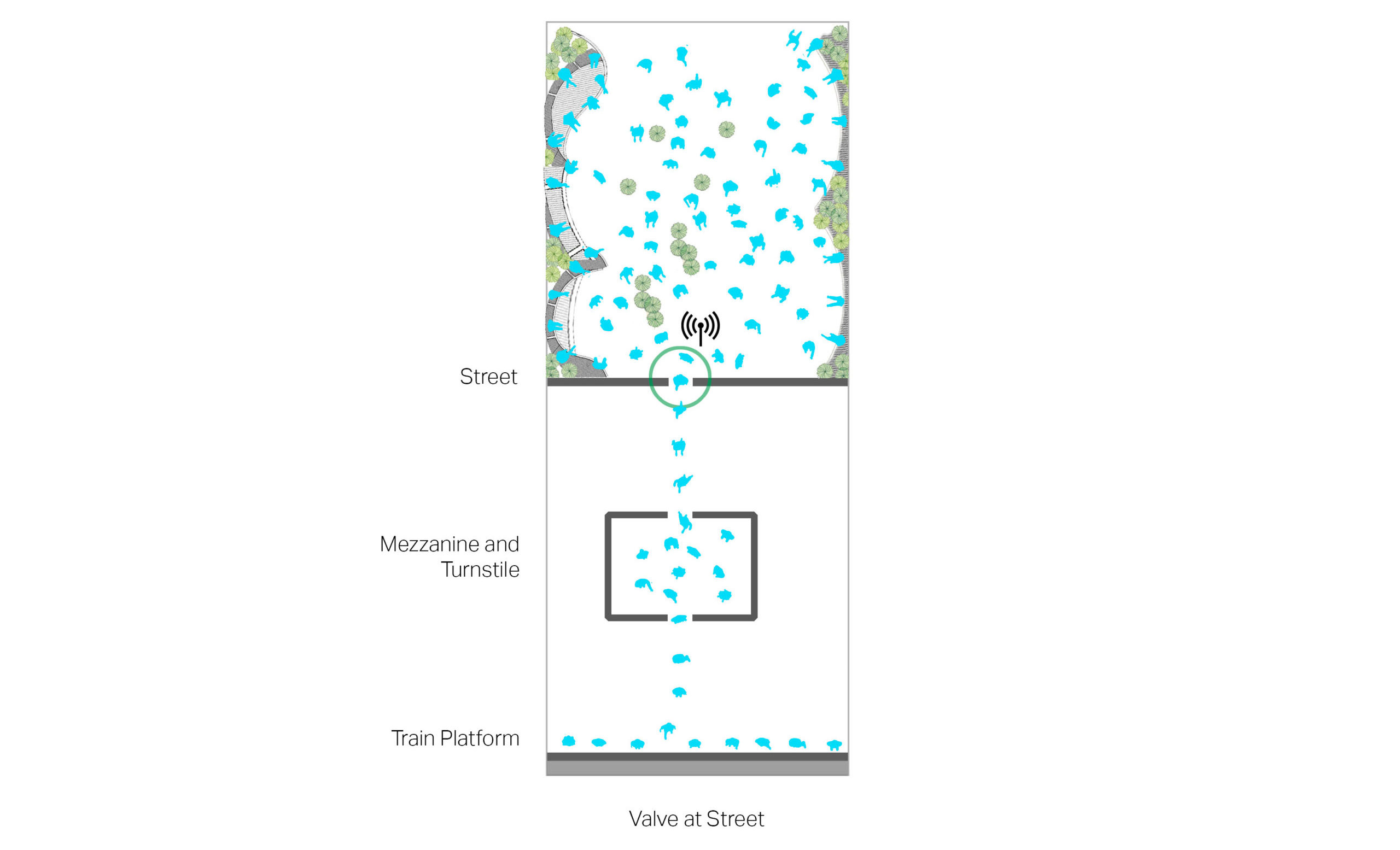

New, street-level pre-boarding areas could provide quality waiting environments, and more fully integrate public transit into the life of the city. During peak transit times, these new public places would also give an indication of wait times to those wanting to board the system before entering it, informed by several sources of data, so people can decide whether to wait or take another route, walk, bike, or use a car service.

And, during off-peak hours, these “social condensers” would function as outdoor public living rooms, assets to local communities, providing room to safely congregate in open air environments as well as space not just for transit users, but also for the general public to sit, meet, eat and drink, and participate in performances and the life of the street. New canopy structures would provide protection from the elements.

Early pilot projects could be constructed quickly and inexpensively to test the concept. When fully built-out, the vision for quality public space at grade, serving as valves for the below-grade subway system, would not only re-establish trust in the safe conditions of our transit systems, but transform how we use transit infrastructure and the associated public realm.

The Need

Restoring a level of confidence in the safety of the transit system is a categorical imperative. Public Transit is the major public infrastructure required for the day-to-day functioning of great cities. Districts that rely on a subway can not get back to business-as-usual until people feel safe taking public transit again. Transit makes these cities accessible, providing equitable service to all, which is why we need to make all stations accessible to all. In some cities, public transit is a last resort for people with no other options. In others, public transit is a choice, more convenient than a car. But in these great global cities with legacy systems, the city as we know it would not exist without public transit. There is just not enough room on the roads to move the additional millions of people every day.

Today, in the midst of the pandemic, the subway is the weakest link in getting back to work and re-booting the economies of major cities. It is not difficult to imagine maintaining safe social distances from home to the subway. And at places of work and other destinations, protocols are being developed to maintain safe conditions and social distancing. Workplaces can be incentivized to help spread out peak transit usage. But while transit agencies nationwide and internationally are trying to manage safety and social distancing in various ways, those who have experienced severe overcrowding on platforms fear that mere suggestions of this sort would have a de minimis effect on transit crowding. The public needs to be able to rely on a fail-safe approach to public health, not just recommendations.

While these initiatives are important, they are not likely to be enough to fully assure people that they won’t be stuck on a train or on a platform in an uncomfortably crowded situation. Bus ridership has rebounded significantly more quickly than subway ridership, because it is easier to exit a bus back onto the street if it feels unsafe – the relationship to the street is visible and direct. Since subway trains and waiting areas are typically not visible from the street, crowding needs to be actively managed and rendered impossible to occur. And crowding must be seen to be actively managed, to engender public confidence that it is safe to use the system again.

While these initiatives are important, they are not likely to be enough to fully assure people that they won’t be stuck on a train or on a platform in an uncomfortably crowded situation. Bus ridership has rebounded significantly more quickly than subway ridership, because it is easier to exit a bus back onto the street if it feels unsafe – the relationship to the street is visible and direct. Since subway trains and waiting areas are typically not visible from the street, crowding needs to be actively managed and rendered impossible to occur. And crowding must be seen to be actively managed, to engender public confidence that it is safe to use the system again.

Pre COVID-19 many stations experienced dangerously overcrowded conditions. Sam Hodgson, The New York Times

Even before Covid-19, many stations and trains were already unsafe. The legacy public transit systems are the largest and most robust systems, global leaders in serving their cities, yet transit users were subject to dangerously overcrowded conditions, often having to wait on packed platforms, unheated in the winter and uncooled in the summer, while full trains passed. The expectation that public transit riders should endure uncomfortable and dangerous conditions on a regular basis reveals an inequity in access to the resources of our cities. We don’t want to return to normal; we need a better normal.

Mass transit systems in legacy cities were planned and largely implemented in a previous era. With recent advances in the availability of big data and our ability to leverage it, the way we use public infrastructure is undergoing a transformation, from traffic apps to deliveries, and ride-hailing services to bike-share. Examples of leveraging the new efficiencies of logistics, made possible by the availability of information and the ability to use it to transform urban systems, abound. Today, with new sources of data available to manage passenger flow and provide options, with minimal public investment, there is a better way.

The Solution

How do we regain the trust of the subway traveler?

To move large numbers of people, part of the solution is simply running trains often enough, with short enough headways to move the required volumes of people while managing the maximum number of people on each car to maintain safe social distances. To ensure that trains are not overcrowded, staff acting as spotters could provide real-time crowd data, and eventually with cameras and visual or audio notifications limit on-boarding, if the on-board conditions are not safe to take-on additional passengers. Some systems already provide information to the public on the relative available capacity of cars on a train. But we remember crowded platforms from pre-Coronavirus days, how crowded they could get when trains are delayed or full, and the sense of not having options having already committed to a specific route. As long as we continue with the current scenario that doesn’t manage the flow of passengers onto the platform, the public will continue to fear overcrowded platforms and avoid using the system.

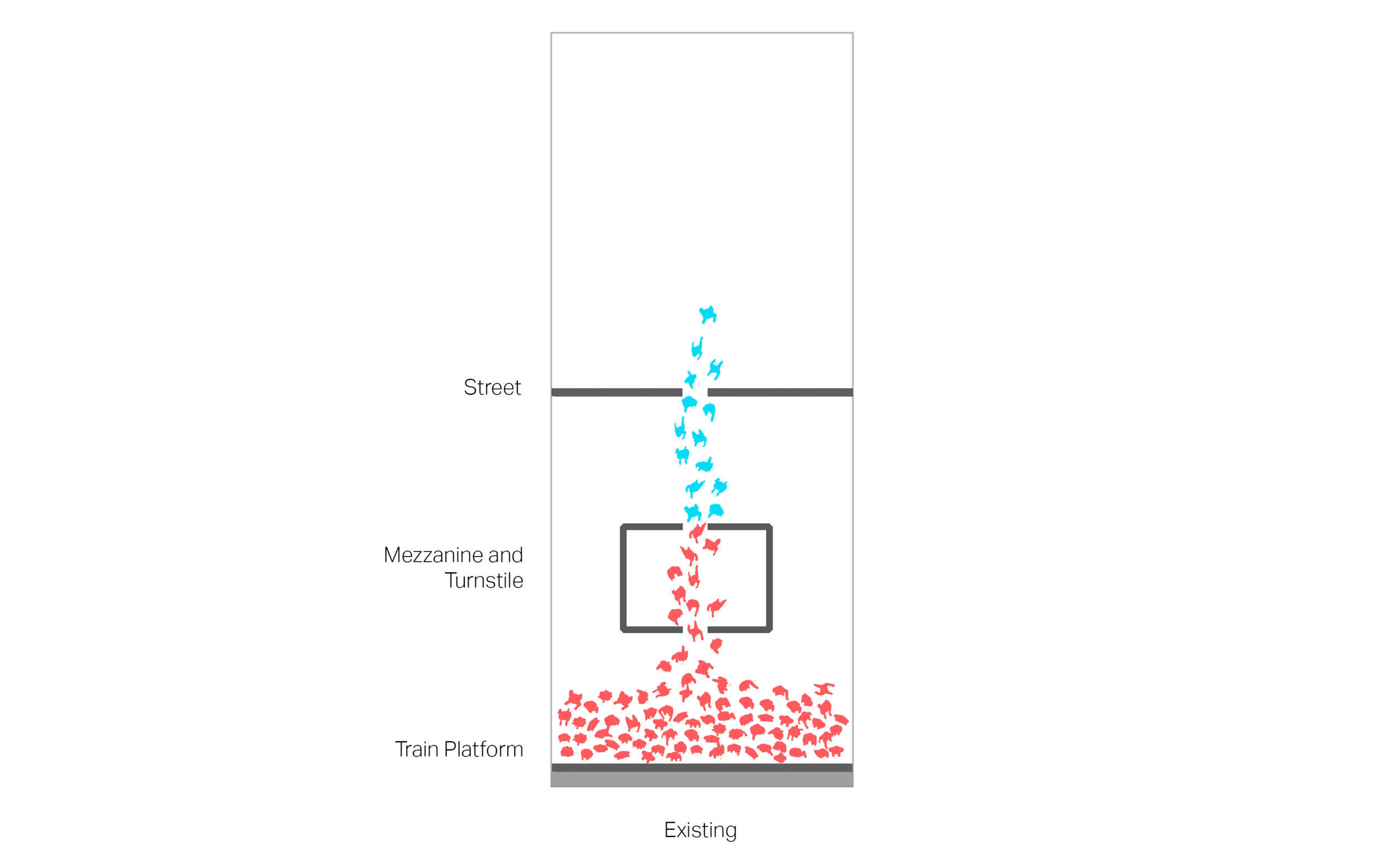

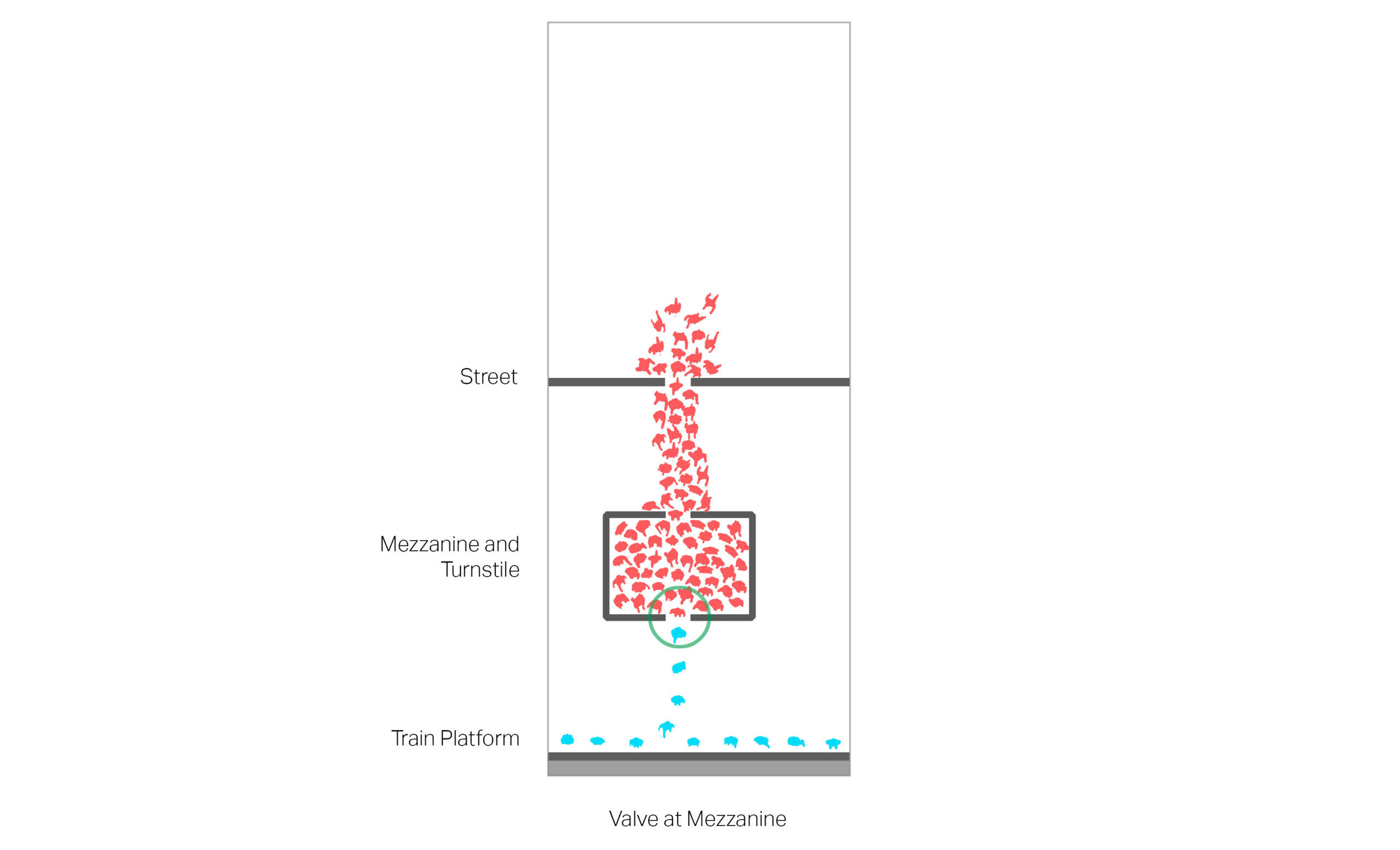

To address crowding on the platforms, the flow of pedestrians onto them must be managed. Can the fare array, typically on a mezzanine between the street and the platform level, or at the platform level itself, also serve as a valve to stop people from proceeding to the platform if there is not enough room on the platform? Unfortunately, there is simply not enough space within the station itself to manage crowds at safe distances. Crowding in the unpaid areas, before the fare arrays, could be even more dangerous than crowding on the platforms, as these areas are typically smaller, and would impede the safe exiting from the station.

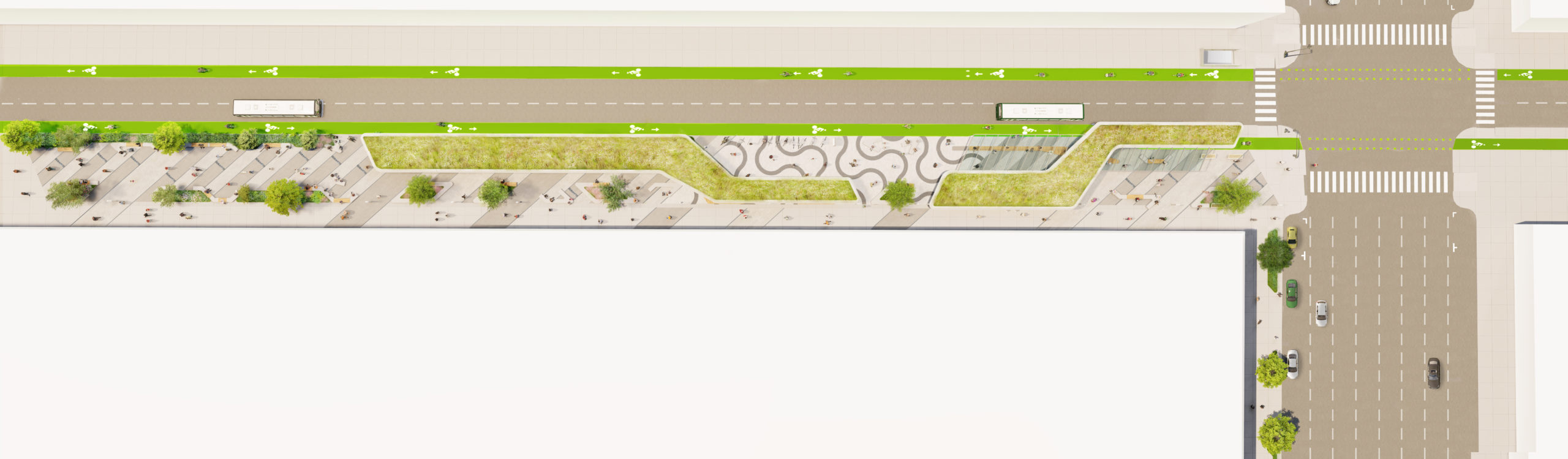

There is a third option: provide an area at street level to wait, so as not to crowd the station or stairs. But where is there enough space for the millions of people to gather before entering the transit system in a timed and regulated manner to assure their safety? In these cities, sidewalks are already at capacity with pedestrians, but drive lanes and parking lanes are used by very few. Waiting pavilions could be located on the street itself, reducing the carriage-way by a lane or two. These new transit centers would act as public squares, contributing to a more pedestrian-oriented and safer street environment, while providing convenient connections to other options for getting to one’s destination, and transforming certain blocks into pedestrian prioritized streets with access for only public transit modes and other essential vehicles.

At station entrances, a monitor will assure that people enter in a timed manner when there is adequate space on the platform, much the way supermarkets have been controlling the flow of shoppers into their stores.

Pedestrian flow simulation of the three scenarios, at a station entrance.

On-boarding passengers could be screened for health indicators, and personal protective equipment, including masks, could be distributed. Phase I of the plan could be readily implemented in a matter of days, with no more investment required than employing a person to manage the line at the top of the stairs, some moveable chairs and planters, and perhaps a tent or simple canopy structure to protect people from inclement weather.

A more robust implementation of the concept could also be constructed with somewhat more planning and investment. Data from satellites, cellphones, turnstiles, cameras and/or sensors could be aggregated and integrated, along with apps and screens at the stations to reserve a time to enter or select alternate transit modes. At-grade entrances could be combined with access to bus service, micro-transit options and ride-share services. The seating, planting and paving for the space could provide welcoming areas to enjoy while waiting and observing safe social distances with clear navigation through the space. These new places would provide a meaningful contribution to the public realm: lushly landscaped public space with places to sit, eat and drink, a place for performances and meetings, and a new way to fully participate in the life of the city.

An aerial view: the investment in transit infrastructure provides value to the public realm and associated sites.

Canopies, planting, fixed and movable furniture provide for a wide range of public activities, combined with timed entrances to transit.

Through all seasons, day and night, the new entrances will manage access to the subway below with accessibility upgrades and public transit data.

The valve allows pedestrians to enter the station when the capacity on the system is appropriate.

The Cost

We recognize that the financial conditions of public transit agencies are in dire straits, due to drastically reduced ridership. But investments that address the root causes of this crises will pay dividends in increased ridership.

It is well-known how costly it is to work on subway stations. An additional advantage to implementing this program to increase ridership with at-grade modifications, rather than below-grade, is that it avoids all the challenges of working within an existing station environment and unknown, hidden conditions, which is a risk to project budgets and arguably the main source of cost overruns. Other than providing new elevators, necessary to meet the project goals of universal design and access, which transit systems are implementing in any case, all work is at street level and should not be any more expensive than regular construction.

The Environment

As public places, these new interventions offer the opportunity to demonstrate the advantages of public transit as we move towards more sustainable cities. With developing climate-change, livable urban centers, for which a functioning transit system is a pre-requisite, present the best alternative to sprawl with its associated inefficient infrastructure. Making public transit safer and more inviting will build ridership and benefit the environment.

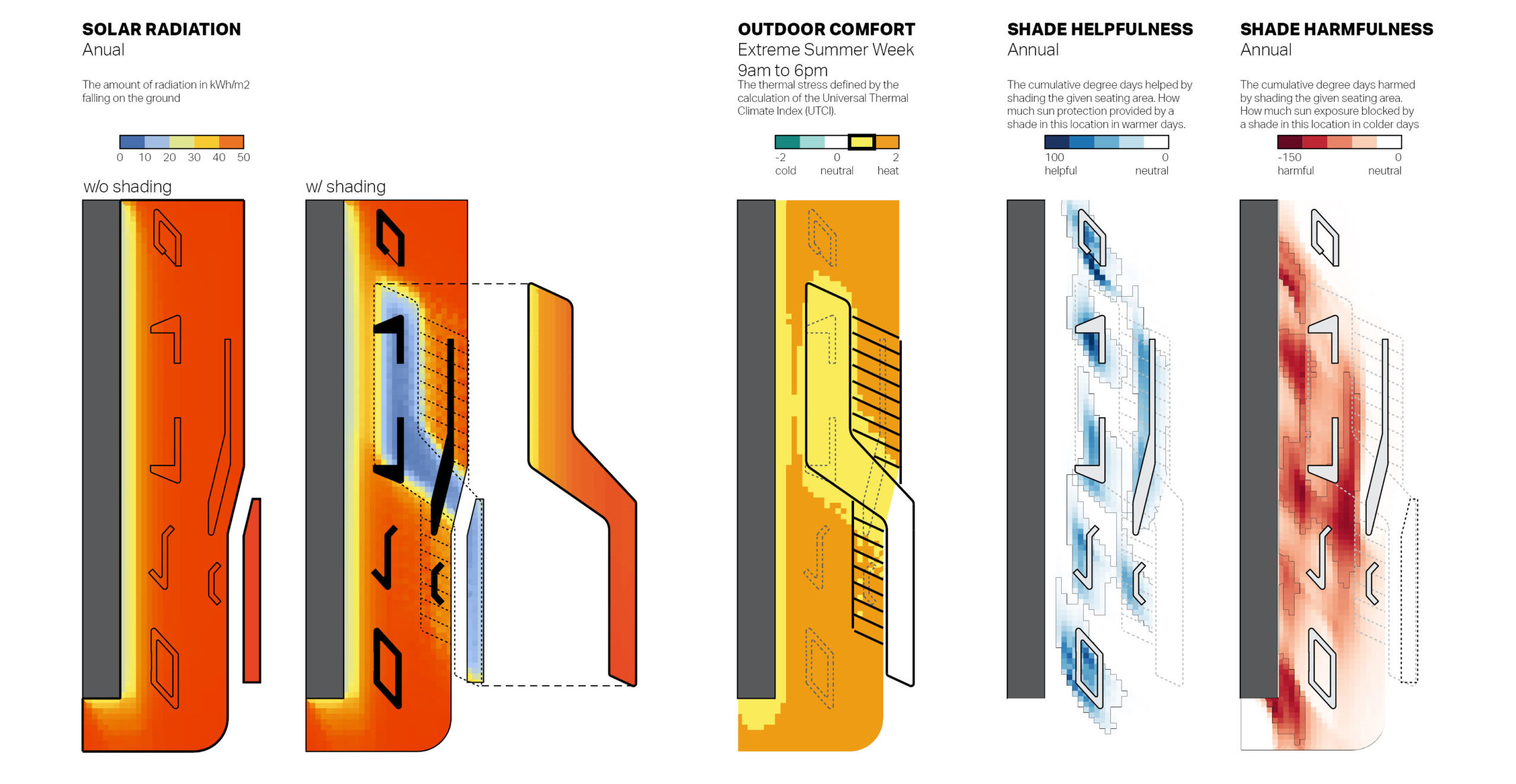

An associated aspect of high-performance transit systems is leveraging environmental conditions to achieve a healthy and comfortable customer experience. In addition to the fact that it is only at the street level where there is enough space to socially-distant gather before getting on a train while conveniently providing passengers with other travel options, locating the waiting areas in the open air allows for much improved air exchange. Passenger comfort can be addressed with smart strategies that leverage solar gain, shading devices, and wind awareness to optimally configure social space.

A pedestrian-level environment analysis can be undertaken to understand the likely solar and wind patterns and feed into an outdoor thermal comfort analysis measured by Universal Thermal Comfort Index (UTCI) which can be used to optimize the location and geometry of the design elements, such as the canopies and the benches. UTCI considers several parameters including wind speed, temperature, humidity, and direct solar radiation and provides a “feels like” temperature value that indicates heat stress felt by a human body outdoors. The purpose of this analysis would be to evaluate, on a typical summer day for example, what thermal comfort may look like at the site, and to quantify the benefits of adding shading in the form of the canopies and trees This analysis of public space comfort informs design options including canopy footprints, benches, and activity locations.

Next Steps

Fully integrating the subway system into the life of the street is a challenge that a transit agency can not address on its own. But great cities are already implementing public plazas in underused streets. Business Improvement Districts are looking for ways to attract people to their neighborhoods with places and activities. City Planning offices and design communities are advocating for a safer, more sustainable and more equitable public realm, recognizing that transit is the gateway to it. Making the street part of the transit system allows for an integrated approach to a high quality and safe experience for subway users.

Let’s find a few promising sites and do some pilot programs to test what works to get our great cities moving again!

AECOM is the world’s premier infrastructure firm, delivering professional services throughout the project lifecycle. We’re planners, designers, engineers, consultants and construction managers driven by a common purpose to deliver a better world.

Walkways: Rediscovering a Mass Mode of Transportation

Every resident of New York City, in all boroughs, needs safe walking routes to parks, grocery stores and other essential needs. Marginalized neighborhoods in the City have less access to open space and amenities than primarily wealthy neighborhoods.

For years, urbanists, architects and community groups have been advocating for the prioritization of pedestrians in the design of streets and the public realm, although by in large motorized vehicles have remained the main protagonists. The discussion invariably centers around mobility, and ultimately vehicles remain our primarily means of transportation.

In the last two months of social distancing and business closures in NYC we have experienced a different kind of street, a shift in its primary role, from moving vehicles to moving pedestrians. As vehicular traffic has diminished, and social distancing has increased the spatial needs of pedestrians, the disproportionate and inequitable amount of street space dedicated to vehicles has been exposed for all to see.

Walking to places is our newly rediscovered mass mode of transportation, and streets are the routes we take. For many in the city, the extent of travel has contracted to the range of our longest walks taken around our homes. This moment is an opportunity to permanently reclaim more street space for pedestrians.

Expanding the network of public spaces the city has to offer, safely linking parks and neighborhoods for pedestrians will improve the city’s health and its people’s health. It’s time we reassert walking as a serious and important mode of mobility that deserves smarter and more widespread planning.

The concept of reclaiming streets for pedestrians has been slowly but steadily building. New York City has seen the pedestrianization of many streets including Broadway, lowered vehicular use streets like the now bus-only Fulton St in Downtown Brooklyn, and of course the widespread new networks of parklets and bike lanes.

Marvel Architects has been active for decades in rethinking NYC streetscapes to prioritize pedestrians. Recently, Marvel has been working with Union Square Partnership developing a plan to fully transform the square into an expanded pedestrian friendly district. This will include the pedestrianization of roadways, road diets and pedestrian safety measures.

We have developed goals and design principles that are applicable not only to areas with high-density or high-visitation rates, but equally in less busy neighborhoods. Every resident of New York City, in all boroughs, needs safe walking routes to parks, grocery stores and other essential needs.

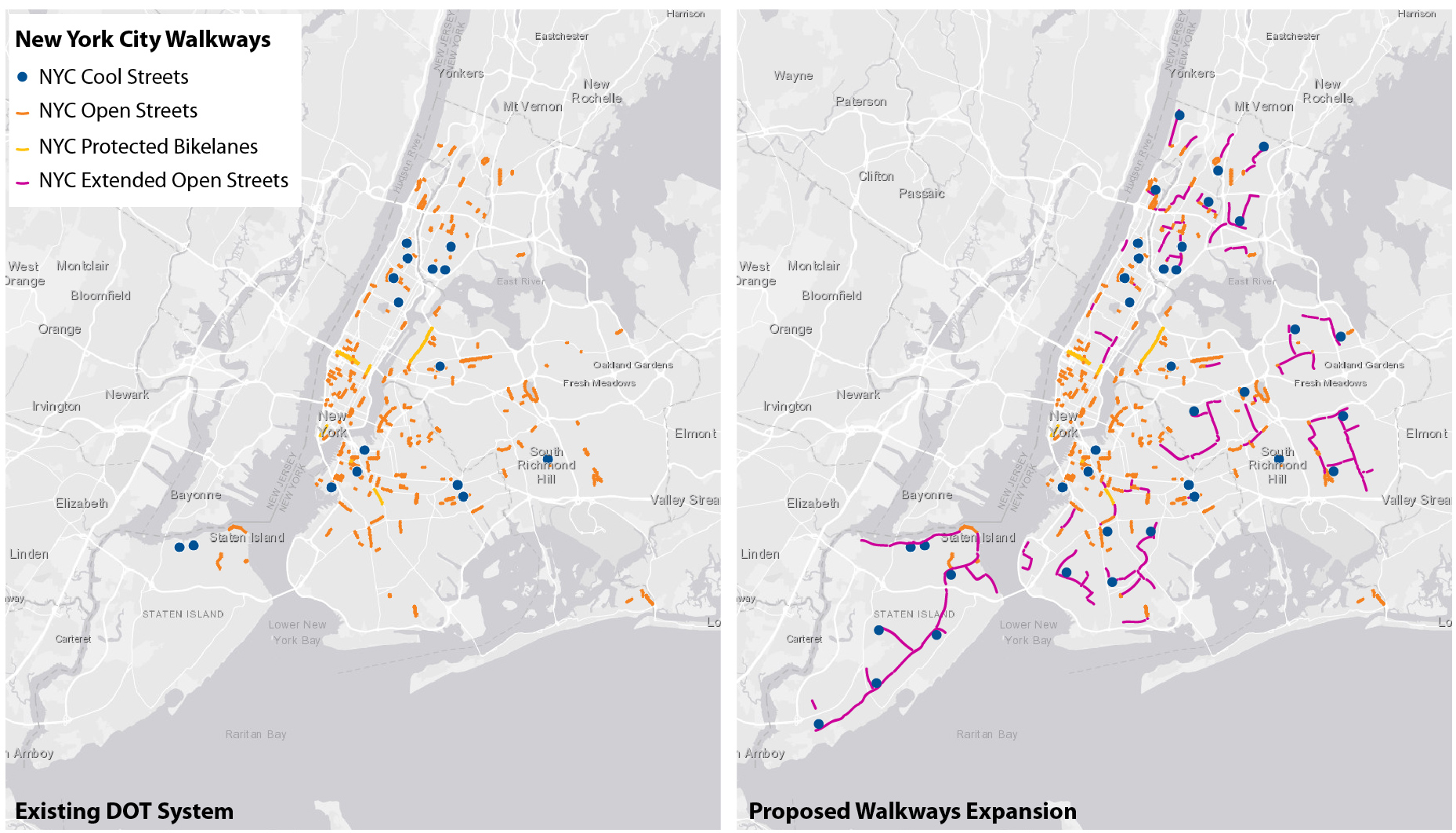

To reimagine “City Life After Coronavirus” we must identify and draw these routes for every neighborhood in the city. To develop a map, similar to the one used to identify subway and bus routes, but for safely walking through the city. It will also indicate potential future extensions and connections.

The space of the street will play a key role as we transition to a post-pandemic city; it is the space where people will queue to wait for food, to enter banks, to get groceries; it is the space where you’ll wait for your turn at the doctor, or to get to a store; it is our gyms and daycares. The implementation of this plan has started with the city’s Open Streets program, but we need to quickly develop a plan that ensures these routes are made permanent and the space of the street is returned to whom it has always belonged, to the people.

Marvel Architects is a solutions-driven design practice that integrates context and nature into every project, meeting each design challenge by listening to its surroundings. With offices in New York and San Juan, Marvel is an international firm dedicated to creativity and diversity. From the New Jersey Institute of Technology to St. Ann’s Warehouse, the team has pioneered an entrepreneurial approach to architecture and place-making that has been recognized by over 125 industry design awards including the AIA’s highest honors.

Regional Government Collaboration Platform: Creating a Networked Region

Coronavirus, like most emerging public challenges, ignores political boundaries. The few successes and many failures of the COVD-19 response have laid bare the paucity of institutional coordinating mechanisms across the extraordinary numbers and levels of government entities. The shortfalls in the pandemic response argue for the creation of a regional collaboration tool for public officials and stakeholders to coordinate across jurisdictional boundaries and levels of government throughout metropolitan New York.

COVID-19 triggered a massive shift to work at home (and for many New Yorkers, work from remote second homes) which has spawned speculation that the viability of New York City is being undermined. Paradoxically, the rapidly adopted internet- based communications platforms, when harnessed to public ends, can serve to reinforce the importance of place. These platforms have demonstrated that distance does not create a barrier to collaboration and there has emerged a new norm that in-person meetings are not required. This means that regional public leaders can now more easily collaborate, and the vast NY metro region can be effectively shrunk through an internet communication tool adapted to public needs.

This proposed internet-based platform could be developed in support of near-term COVID-19 response efforts, but ultimately would strengthen the region to confront imminent challenges from rebuilding after COVID-19 to responding to the stresses of climate change.

Lessons from COVID-19:

- The public sector is disorganized at a regional level. There is no forum for addressing long-standing regional problems, such as the disconnect between regional transit investment and local land use policy, let alone novel emergencies such as COVID-19.

- Expert and well-considered opinion is increasingly ignored in public discussion where loud and uninformed voices often prevail.

The disorganized COVID-19 response at the national level was amplified by the disdainful rejection by many leaders of scientific judgment —the spotlight was thrust on the states. The multi-state collaboration initiated by Governor Cuomo developed action principles followed by a reopening organized through multi-county regions. Although ad hoc, the regional cross-jurisdictional COVID-19 response created a consistent message of response, and developed criteria, based on data, for re-opening.

The same cross-jurisdictional approach supported by professional advice and data is seen in Italy’s successful COVID-19 recovery. Its government is guided by scientific committees backed by local health officials who daily gather data on key virus indicators and send them to regional authorities, who then forward them to national authorities. Government policy decisions are based on a weekly snapshot of the country’s health.

Proposal:

Starting with the three metro NY states, a networking and information platform for regional and inter-municipal coordination should be created. This is not intended to be a public forum – although key elements would be publicly available. This networking and information platform would have two primary functions:

- Link local and state level officials, citizen stakeholders and agencies, and provide discussion forums and access to information and other resources to help local officials address issues which are regional in nature or have regional implications.

- Aggregate and curate objective data to provide regional snapshots to policy makers – travel patterns, construction permits, employment figures or health indicators, for example.

The platform would link to existing state and local data bases and eventually would include privately generated and aggregated data that under future data laws could be made publicly available. It would also generate and provide opinion data unique to the platform, such as creating a regular leadership opinion survey of critical issues that could serve as a public advance warning of emerging issues, whether environmental, economic or social.

The platform should be coupled with a mandate from each participating state that public officials consider regional views when taking actions, which parallels existing requirements that environmental impacts are taken into consideration. Regular leadership surveys could provide insights to other leaders and the public on emerging issues. Discussion forums could debate proposed actions informed by a range of professionals and stakeholders who have defined access privileges to the forums.

Over time the platform could provide a counterweight to the “loudest voices syndrome” and internet “outrage” where in public meetings, on the internet, or in the press the most extreme views get the greatest airtime. These forums would not be intended to eliminate extreme views, but would serve to put them in context of other approaches with reasoned responses.

Infrastructure investment, for example, requires a long term and regional perspective to design and finance which contrasts with the local, short term perspective typical of most public discussion. A striking case was the Hudson River tunnel project (known as ARC) which was abruptly cancelled in 2010 after nearly two decades of design and funding efforts conducted largely out of public view.

Surprisingly for a project of such regional importance, the cancellation generated little discussion among regional leaders, the general public or the press. Had a regional communication platform existed, the ARC project may have been more generally known and debated and the action to terminate it may have flashed a warning signal on the regional platform, alerting leaders and, perhaps, encouraging solutions to save the project.

Rationalizing and streamlining inter-government communications through a common platform could have many regular applications. The platform could help coordinate land use policies among neighboring jurisdictions and affected stakeholders in a more fluid and productive manner than the prescriptive and formal communication used for environmental review.

It could assist in aligning local land use policies with regional transportation investments. The platform could facilitate inter-municipal initiatives ranging from developing and implementing shared service delivery to coordinating affordable housing policies. This platform could also assist existing initiatives such as New York State’s Regional Economic Development Councils with both internal coordination among council members and outreach to key stakeholders.

Key elements:

Capacity to encourage networks of public officials and stakeholders. Broad inclusion in the network would have elected officials, public officials and stakeholders admitted through a gating process. This would not be an open public forum, although views and ideas generated would be made public. The platform would overcome the enormous scale of the New York region. Interchange would be routine, not ad hoc.

The network would create value for participants; new ideas and successful initiatives could quickly be disseminated and discussed, critical information and data would be readily available. Regional and state decision makers would be informed of local conditions and views. At the same time, there should be legislative mandates that local officials take regional views into account even with respect to local matters. Over time this networking could help foster a greater sense of regional identity and purpose.

Leadership surveys and real time data. Regularly taking the “pulse of the leaders” and publishing this survey information would identify issues confronting localities and gauge leadership views of proposed solutions. Surveys of the opinions of those who bear the responsibility of confronting problems as well as of professionals engaged with specific issues can provide context for public discussion.

Platform data could be available initially by tapping into publicly generated information and eventually should incorporate large-scale data about the public which is privately generated and held but which should in the future be available for public use and benefit through negotiation or legislative mandate.

Implementation. This platform can be constructed initially to support regional COVID-19 responses and the officials and jurisdictions involved. The network should be broadened to include a full range of subject areas and expanded to add jurisdictions. Eventually this initial tristate forum might add contiguous states and even beyond.

The tool would not replace existing decision-making processes; instead it would help inform them. It will not eliminate disputes and political confrontation. Different stakeholders with differing interests will still have competing goals. It should, however, reduce the inherent distrust and inefficiencies resulting from our existing governmental fragmentation where public officials rarely interact across jurisdictions, and where even neighboring towns typically don’t collaborate.

There will be issues of governance and rules as this tool is created, but just the process of setting it up should help to create bonds among separate jurisdictions that are often not in communication.

One physical result of the pandemic is the potential expansion of what is considered to be the New York region as work migrates to places outside the traditional commuting boundaries of New York City. This follows the pattern of prior periods in which epidemics and new technology acted to disperse New York’s economy and population.

However, in each case, public initiatives effectively harnessed the power of new communication technologies which reinforced New York’s central role in the periods when canals, then railroads, then telephones came to dominate. This is the time for the public sector to respond to the digital age.

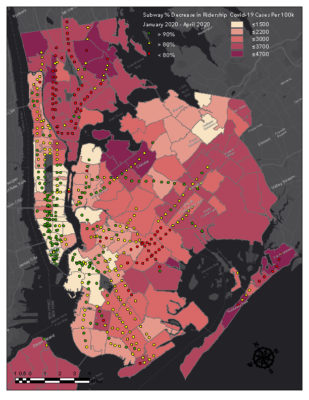

An Analysis of Subway Ridership During the Pandemic

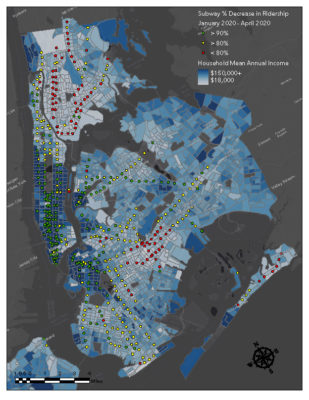

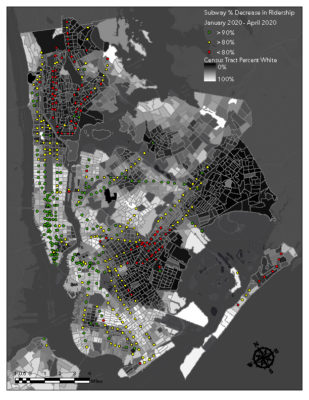

The following maps were created in order to explore the ways in which Covid-19 has affected subway ridership as well as how the effects vary spatially across the city. In order to explore this topic we took a look at subway ridership change by station between January 2020 and April 2020 (when Covid-19 was rapidly increasing in NYC) over three different metrics: Covid-19 case rate by zip code, income by census tract, and population percent white by census tract.

Income and demographic data for NYC was acquired from the American Community Survey (ACS) which is a demographics survey program conducted on a yearly basis by the U.S. Census Bureau and uses a series of monthly samples to produce annually updated estimates for the same small areas (census tracts and block groups) that the decennial census uses. Covid-19 case rate data was acquired from the NYC Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Data repository. This data is reported using modified ZIP code tabulation areas as opposed to census tracts.

The case rate map shows that the areas with the greatest reduction in subway ridership, for the most part, have experienced the lowest rates of Covid-19 across the city. This is not to say that riding the subway directly causes Covid-19 cases, but instead that those that continued to ride the subway after Covid-19 began are more likely be essential workers and therefore are still required to go to work and be exposed to the virus in many ways other than the subway. We can see that the outer boroughs are the most affected and likewise have had the smallest reduction in subway usage; this is likely because the outer boroughs are generally less affluent than Manhattan and have a higher portion of low income workers who are unable to work from home during the pandemic. Additionally, those who live in Manhattan are more likely to be able to walk to work and during the pandemic many who normally take public transit may have decided to walk instead.

The income map shows that lower income areas had less reduction in ridership when compared to areas of higher income. Higher income areas are places where people have jobs that allow them to either work from home, stop working all together, or to leave the city for country homes. This caused a steep decline in subway ridership in these areas whereas in lower income areas people are less likely to have a job that is work from home compatible and more likely to be essential workers which caused the subway ridership to decrease much less.

This map shows that predominantly whiter areas are more likely to have experienced a drop in subway ridership compared to less predominantly white areas. This is likely because the non-white population is more likely to have a job that requires them to continue to commute to work during the pandemic and displays that a large portion of the city’s essential workers are Black and Latino populations.