The development of community fridges, mutual aid networks, and other local initiatives have shown that neighborhood-led recovery strategies are essential in meeting the needs of local residents. How does creating self-sustaining neighborhoods aid in building resilient cities? These exciting proposals feature ideas that focus on improving the quality of life for residents on the scale of the neighborhood, and even the block. By creating these bustling hyperlocal networks, we can find solutions to targeted issues and create stronger community ties. Scroll to read all 6 proposals.

Strengthening of the Hyperlocal

Re-Activating the Corner Store

Responses Continued ↓

Building a Resilient New York City by Carlos Arnaiz, Peter G. Rowe, and Gaby San Roman

Microcosm: Creating Decentralized and Resilient Food Systems by Nikita K

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Urban Design Forum launched City Life After Coronavirus, a digital program convening Fellows and international experts to document global responses to the current crisis and to strategize a road to recovery for New York City. In April, we released a Call for Ideas to our network soliciting a broad range of submissions that envision how urban planning and design should change in the wake of Covid-19 as we strive to build a more just city for all New Yorkers. We are featuring some of the most compelling ideas in a series of reflections and proposals about diverse topics like education, community engagement, and mobility. Explore the full Gallery of Urban Ideas here.

Strengthening of the Hyperlocal

[RE]USE

[RE]SHAPE

[RE]THINK

[RE]URBANIZE

[RE]SEARCH

[RE]ZONE

[RE]PROGRAM

[RE]CONNECT

[RE]CONSIDER

[RE]SET

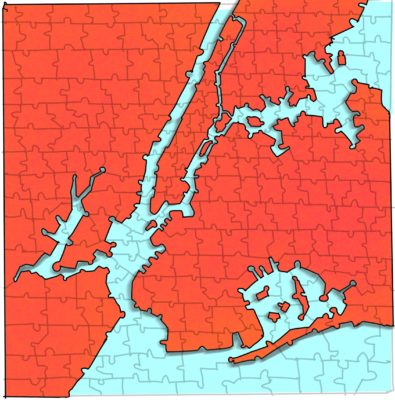

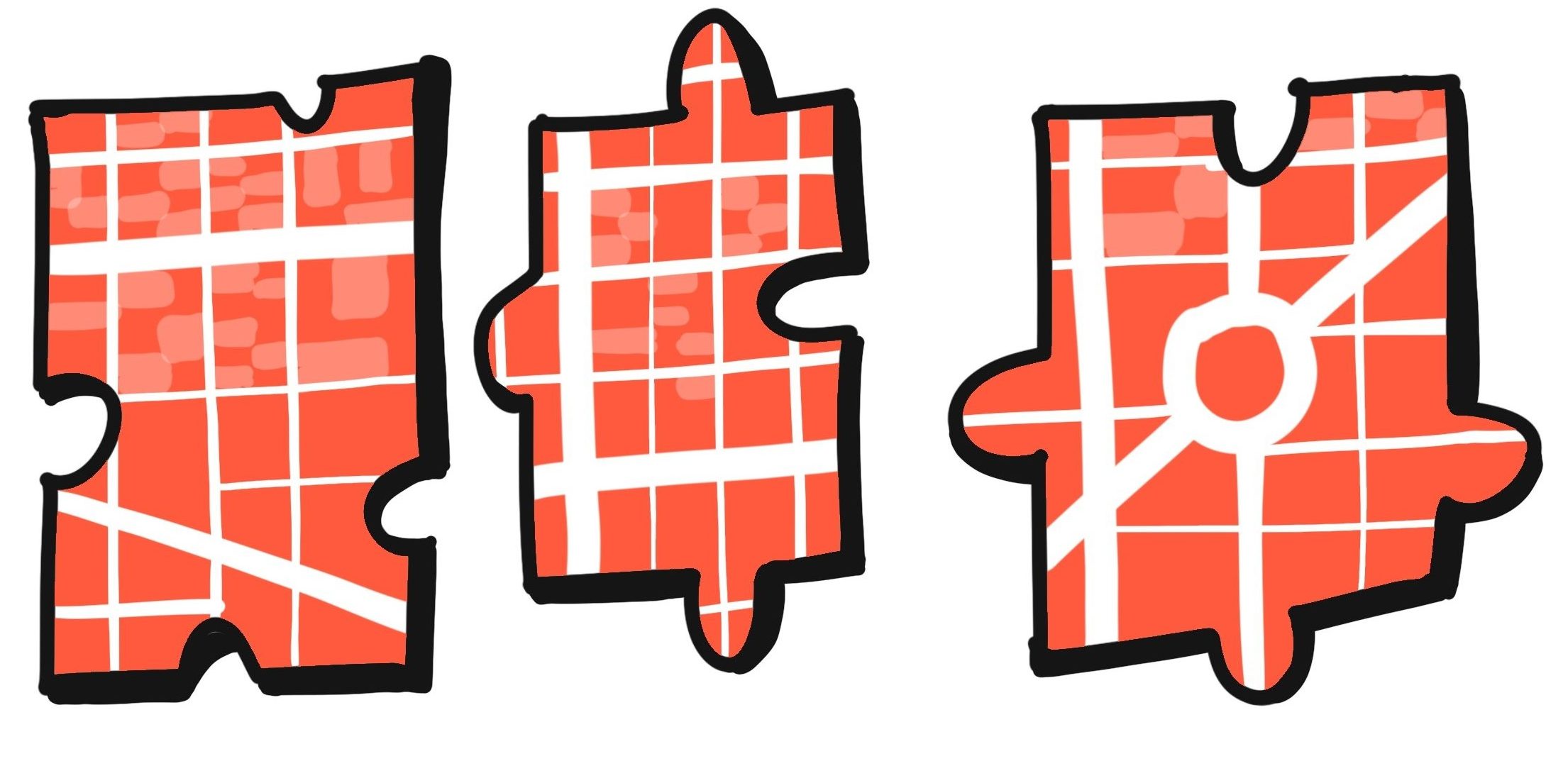

COVID-19 has abruptly separated us from our vast geographical infrastructure we had

come to rely on. Now confined to walkable distances in our immediate neighborhoods,

communities are forced to return to simpler times when cities were a collection of villages,

but all too often without the local businesses and civic infrastructure required for them to be sustainable. Like pieces of a puzzle gone missing over the years, so have these district- focused elements; independent grocery stores, health clinics, museums, schools, small businesses, and safe places to socialize. The pandemic has refocused what we consider to be our community by suddenly narrowing the radius of available resources. Urbanists previously identified this trend, but it took the drastic nature of a pandemic to clearly illustrate how unbalanced modern metropolitan life has become. To ensure the successful growth for all inhabitants of the city, the local village – the hyperlocal, must be resurrected.

It is not simply identifying the missing pieces but re-crafting them to create livable neighborhoods. Through a shift in mindset at all levels – government, community, enterprise – coupled with the collaboration of planners and architects, we can take a step back to envision a complete puzzle with its interlocking parts of connected communities that re-create a robust, well balanced and sustainable city.

It is not simply identifying the missing pieces but re-crafting them to create livable neighborhoods. Through a shift in mindset at all levels – government, community, enterprise – coupled with the collaboration of planners and architects, we can take a step back to envision a complete puzzle with its interlocking parts of connected communities that re-create a robust, well balanced and sustainable city.

Within the city – not to the city

As NYC’s population continues to grow, a neighborhood’s walkability and capacity to provide for its residents must be prioritized in order to minimize the strain on our citywide infrastructure systems. Self-sustaining neighborhoods reinforce residents’ sense of belonging, and make their communities safer and stronger. Could the success of our city be found in the strengthening of the hyper local?

Not more but better

Rather than only fortifying existing citywide systems, brazen development, or expanding city sprawl, how might reworking a neighborhood’s fabric, in collaboration with residents, create a resilient and vibrant city? We are told more trains will solve the subways, but what if we reduce the need for them, by providing better opportunities for learning, employment, and leisure in communities where people live? By supporting underdeveloped infrastructure in neighborhoods can we ensure their health and sustainable growth into the future? We should shift our focus to building our social infrastructure.

Toward equilibrium

Could essential infrastructure that sustains neighborhoods, such as clinics, schools, and small businesses, serve the local walkable community to sustain the local economy while also being part of the greater city-wide network?

Why this – Why now?

COVID-19 has brought a world-wide level reset that has shown how unbalanced modern metropolitan life had become. It has forced us to re-evaluate how the hyper-local needs to be re-thought, re-used, re-zoned, re-connected, and re-considered. What exists is not new. What is new – is the opportunity to act (now).

We cannot return to what was previously deemed “normal.” Locally-based social networks have played a vital role during this pandemic, and with the proper re-set, they can continue to play a leading role towards creating a more socially, economically, and environmentally resilient New York City.

Hyperlocal; The City REimagined

The hyperlocal refocuses on the well-being of the local neighborhood by relocating its basic needs within walkable distances. With this as its foundation it also advocates that essentials, meaning uses that empower and enrich the individual and collective, are integral to these neighborhoods. Through this approach it ensures communities are both self-sufficient and part of a larger city-wide network that is socially, culturally, and economically resilient. In strengthening this network of human centered streets and cross-programmed uses it becomes connected, alive, and safe.

The common thread within the network of hyperlocal neighborhoods is the community hub which acts as the catalyst to neighborhood engagement by providing the space to learn, gather, and promote change – to meet the civic and cultural demands of today. The hyperlocal offers equity of choice of how we live within our city.

Now is the time to REshape, REconnect, and REimagine the local.

the hyperlocal is human centered

the hyperlocal is walkable and bikeable

the hyperlocal fulfills both basic and essential needs

the hyperlocal is small-scale cross-programming

the hyperlocal is sustainable and resilient

the hyperlocal is socially equitable

Andrea Steele Architecture (ASA) is dedicated to accessing the humanity inherent in the design process. We see architecture as the medium through which we define our shared experience and our practice as a catalyst for cultural advancement. Every project we undertake, from a modest private residence to a large-scale civic complex, is rooted in the idea of building a global community.

Nine Reciprocities: Reimagining the Power of the Block

An architectural, financial, environmental, and social model for living block-by-block

Block 162, Chinatown, NY

2021

Nine Reciprocities explores the ways in which forms of dense, urban living can be adapted and redirected towards collective futures and ecologically equitable structures for the future. Nine Reciprocities proposes an architectural, financial, environmental, low-carbon, and social recipe for Block 162, a mixed-use group of existing buildings in New York City’s Chinatown. By maximizing the block’s Floor Area Ratio (FAR), the community of workers, retirees, experts, and visitors inhabiting the block can expand their space in a cross-laminated timber “overbuild”, utilizing existing foundations and footings to create new social spaces, workshops, daycare, parkland, and home offices.

Construction and demolition material is recycled within the block as partitions are removed, finishes replaced, and overbuilds expanded: a system of trombe-wall gardens grows over time, making oxygen, and sequestering carbon. Collective self-government, Tenant-in-Common financing, and sweat equity systems coordinate labor, services, and ownership. A system of trade apprenticeship builds knowledge within the block, without bias toward digital or physical work, transferring expertise through generations.

COVID-19 has exposed critical oversights in our existing understanding of social contracts and the value of labor, highlighting the need to jump-start and strengthen these social ties to combat future epidemics, economic downturns, and approaching ravages of climate change. Beyond responding to the public health problems posed by the structures of pandemic and quarantine, Nine Reciprocities looks towards emerging and intensifying issues of urban social equality and environmental collapse, building a reciprocal framework between humans, societies, materials, and the environment.

Focusing on Recovery at the Neighborhood Scale

At HLW, we feel that a unique opportunity exists to acknowledge and mitigate some key societal inequities in many New York City neighborhoods through community-based, decentralized urban design strategies. In the midst of a global pandemic that has impacted New York City deeply and irrevocably, the daily experience of communities that were already in a perpetual state of crisis pre-Covid has been made exponentially worse. The structural issues that support this crisis-state are the focus of our proposition.

We propose that City Life After Coronavirus should be imagined comprehensively, audaciously and equitably. We see this approach applied at three scales: Small, Medium and Large. From light-touch tactical interventions that people directly engage, to formally-coordinated neighborhood-wide planning, which provides access to distributed public services and greater political self-determination, each of these proposed solutions is to be seen as part of a comprehensive network for renewal.

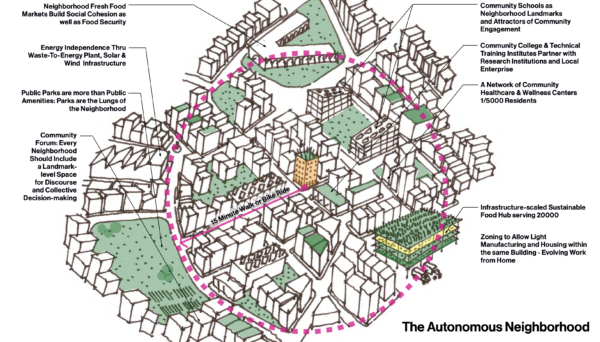

Large Scale

The large-scale response will capitalize on the more positive effects of post-pandemic nationalism, reduced global dependency and decentralization. Urban communities, particularly communities in crisis, will be better places to live through more self-sufficient networks of services, enterprise, and education. Neighborhood infrastructures of sustainable food production, energy and waste management systems, and responsive transportation networks, combined with more direct political representation, will result in the firmer foundations on which healthy communities are based.

The current crisis further reveals the inequalities of our cities and its infrastructure. The concentration of high emission and high pollution industries in low income neighborhoods reduces local air quality and adds yet another infectious disease risk factor that raises the mortality rate and lowers life expectancy of those facing systemic poverty. Large scale responses will push for equitable distribution of environmental initiatives throughout our cities so that nobody has to live with increased health risks just because of their zip code of residence.

This transition away from the megalopolis city-state to the federation of neighborhoods requires a multidisciplinary (architecture, planning, engineering, art, public health, etc) response that embodies the re-democratization of public space, including parks, streets, and squares.

The Autonomous Neighborhood

Neighborhood institutions such as community forums, schools, markets, and cultural facilities will be landmarks that require new architectural typologies. For example, instead of borough-based jails, why not develop an integrated network of restorative justice services? Instead of food deserts, why not create centralized markets supplied by infrastructure-scaled urban farms and community gardens?

Instead of large institutional-scale hospitals, why not a more robust network of community run wellness centers integrated at the threshold of residential and commercial districts that advance public health missions during normal times, which also have the capacity to scale into acute care centers during times of crisis? Public spaces, enhanced by humanistic design approaches and embedded technology (based around public service) will be the new live / work / play environments for healthy communities.

Medium Scale

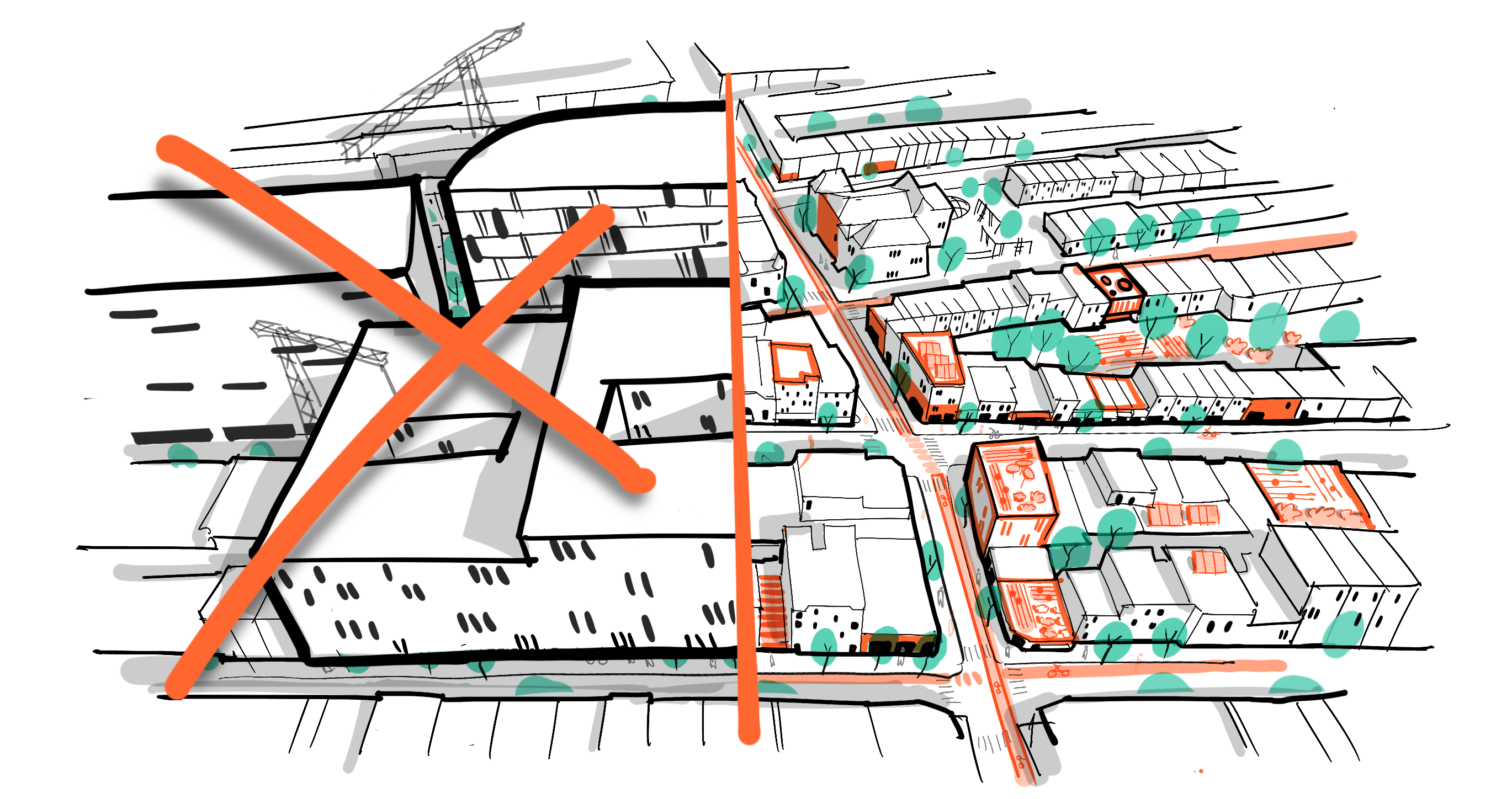

The medium-scale response supports this notion of more self-reliant neighborhoods through a focus on streets. In a post-pandemic world where interior environments will gradually be transformed into healthier, sustainable, “breathing” spaces, the street is the first refuge. The market street, the promenade, the mews, and the vest-pocket parks have all outlived the world’s greatest cataclysms. These spaces represent millennia of human urban occupation and should be the building blocks for a healthier future. The immediate inclination of many (who could afford to) has been to flee the city. Those remaining have largely stayed indoors under government mandate.

The Street Designed for Distance + Density

Streets have been nearly empty of cars and trucks. Air quality has significantly improved, and the sounds of birds have replaced traffic in pandemic-ravaged cities. Evening gratitude celebrations of healthcare and services workers have filled our streets every day with music, applause, and the sounds of resiliency. Will post-pandemic cities become choked with traffic once life returns to “normal” and former urbanites drive in and out every day from the suburbs? This was the case in 1970’s New York, following massive flight from failing urban infrastructures and quality of life. Will these acute changes inspire permanent solutions to our city streets? With time and space on the side of progress, now is the time to accelerate traffic calming and re-pedestrianizing plans that have already been proposed.

Streets have been nearly empty of cars and trucks. Air quality has significantly improved, and the sounds of birds have replaced traffic in pandemic-ravaged cities. Evening gratitude celebrations of healthcare and services workers have filled our streets every day with music, applause, and the sounds of resiliency. Will post-pandemic cities become choked with traffic once life returns to “normal” and former urbanites drive in and out every day from the suburbs? This was the case in 1970’s New York, following massive flight from failing urban infrastructures and quality of life. Will these acute changes inspire permanent solutions to our city streets? With time and space on the side of progress, now is the time to accelerate traffic calming and re-pedestrianizing plans that have already been proposed.

Small Scale

Small-scale responses are the most immediate and deployable now and during the earliest days of post-pandemic life in cities. It involves providing fast, reliable healthcare and health security to all communities, but particularly to communities in crisis. It is realized at the street, on street corners and spaces accessible by all. The current urban healthcare infrastructure tends to be centralized and focused around areas of concentrated wealth and resources.

What if all communities had access to convenient, safe, and effective testing and counseling during flu season? How would the spread of coronavirus during the winter of 2020 been affected by the availability of these kinds of services? We believe that the implementation of small-scale interventions that have large-scale impacts results in immediate and effective progress toward a larger vision of decentralized and self-sufficient communities serving all New Yorkers.

We envision a system of lightweight, deployable, and inviting structures with a kit of parts that will be quickly produced and deployed throughout the community within the next six months. These testing and counseling facilities could be mobile (truck-based), stationary pods, or embedded within existing institutions, such as schools or libraries. They could be all three of these, utilizing a similar set of components. The physical facilities will be augmented by a digital backbone providing information and direct access to hospitals and healthcare professionals. As the pandemic moves from urban centers to rural hot spots, these facilities could be moved to where they are most urgently needed.

As the weather warms and as more people venture outside, street level commerce will gradually proliferate. To maintain safe social distancing while we continue to live with the virus in our presence, we see an opportunity to open up city businesses onto the sidewalks and possibly into newly reclaimed street space. We envision a semi-permanent model of street-based commerce that mirrors the various holiday markets that abound major public parks like Union Square and Bryant Park during the end-of-year holiday season.

Fresh outdoor air has natural benefits over some indoor air systems. In the near term, outdoor shopping may be safer than venturing indoors, so why not invest in a kitof-parts for small and medium-sized businesses to help them bring their commerce to the streets and reactivate street life in a potentially long lasting way?

Our mission at HLW is to question the norm, design with passion, and build what’s next. We were established in 1885 and have continuously evolved to stay at the forefront of architecture and design. From designing the first dedicated telephone building in New York City to our current work with mega tech companies, HLW has a legacy of combining elegant aesthetics with innovative technologies.

Re-Activating the Corner Store

The future of retail and storefront services in cities is in question—it has been for some time. Long before COVID-19, it was urban flight to the suburbs (and their malls); more recently it’s been the onslaught of e-commerce. The current pandemic combines the threats of both of these disruptions: risks (both real and perceived) of traversing the streets and the allure and convenience of online commerce options.

Neighborhood retail services have always been a different animal than downtown commercial corridors. In fact, before the pandemic, there was evidence that urban residents were increasingly relying on nearby neighborhood amenities. And this was a time, not long ago, when people easily moved around the city for work and leisure. But now, and for the foreseeable future, people will be tethered to their neighborhoods unlike anytime in recent history. Mobility across the city will slow down—more people will be working remotely and travel will be skewed towards walking, cycling or, for those with access to cars, driving. One’s local neighborhood will be logistically easy and physically safe. On a more visceral level, the neighborhood is also familiar. Routines of accessing services, knowing how to safely navigate spaces, and seeing the same set of faces all provide some level of security as we cautiously emerge from our quarantines.

We will be testing in real time whether distance matters—the advantage of proximity that cities have always had, but that has been chipped away as remote technologies have taken hold. We will see more clearly the differences in how people rely on and interact with their neighborhood services. Which neighborhoods have access to essential services, like supermarkets and pharmacies? Which households seamlessly shift to online shopping? Where do essential workers, who have to leave their neighborhoods, live and will retail in those footloose communities be more or less vulnerable? As a believer in the physicality of cities, I remain optimistic that this crisis will lay bare the limits of remote living. My own research has empirically documented the co-dependence of retail and neighborhood vitality, a relationship that is entirely based on physical proximity.

People will want to connect, and they will turn outward—and re-engaging with local establishments and services will be part of the recovery. Patronizing neighborhood retail will be both economically revitalizing and psychologically fortifying. Could this be a moment for urban retail?

It won’t happen without some concerted effort, on the part of government, communities and the businesses themselves. Time and income have been lost—the disruptions of the past few months will push many small businesses off the tightrope that they have walked for a while. For those that have managed to hang on, either by staying open and adjusting their operations or by accessing financial support to stopgap the losses, they know that the pace of business will not be the rush that they need. We still need financial reinforcements—after any disaster, the biggest losses for storefront businesses, often not covered by any insurance, are due to the interruption in consumers. That loss will continue to need to be remedied for some time.

However, businesses also need operational support. Guidance on how to adapt their storefront to minimize health risks. Material support and regulatory flexibility for retrofitting spaces to serve customers safely and to protect their employees. Training on how to leverage online platforms for selling and promoting their goods and services. Help with access to new distributors as supply chains shift. Relief from permitting processes and fines that burden already fragile businesses. Opening up the streets for retail displays and restaurant seating (while eliminating parking spots and discouraging car usage at the same time). These are interventions that should be considered during normal times and that need to be accelerated now.

And consumers need to do their part. Supporting neighborhood businesses has always been just as much about community investment as it is about individual convenience. What better time to capitalize on this mentality than during this pandemic, which has been an extended exercise in individual sacrifice and community preservation. Instead of going online to purchase that shampoo or carton of milk, walk down the block and support your local store. And if they don’t have what you need, tell them instead of using the easy online route. If you don’t feel safe patronizing their establishment, tell them why. This will need to be a collective effort, as the businesses cannot survive without our support, and our communities are worse off without their services. Hopefully our investments now will sustain the health of our neighborhoods well beyond the threat of COVID-19.

References

1.Thompson, Derek. 2017. “What’s Causing the Retail Meltdown of 2017.” CityLab.

2.Farrell, Diana et al. 2017. Going the Distance: Big Data on Resident Access to Everyday Goods. JPMorgan Chase Institute.

3.Kolko, Jed. 2000. “The death of cities? The death of distance? Evidence from the geography of commercial Internet usage.” In Ingo Vogelsang and Benjamin M. Compaine, (Eds.) The Internet Upheaval: Raising Questions, Seeking Answers in Communications Policy,” pgs. 73-98. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.; Glaeser, Edward L., and Giacomo AM Ponzetto. 2007. Did the death of distance hurt Detroit and help New York?. No. w13710. National Bureau of Economic Research.

4.NYC Dept. of City Planning. 2016. Resilient Retail.

5.Farrell, D. et al. 2020. The Early Impact of COVID-19 on Local Commerce Changes in Spend Across Neighborhoods and Online. JPMorgan Chase Institute.

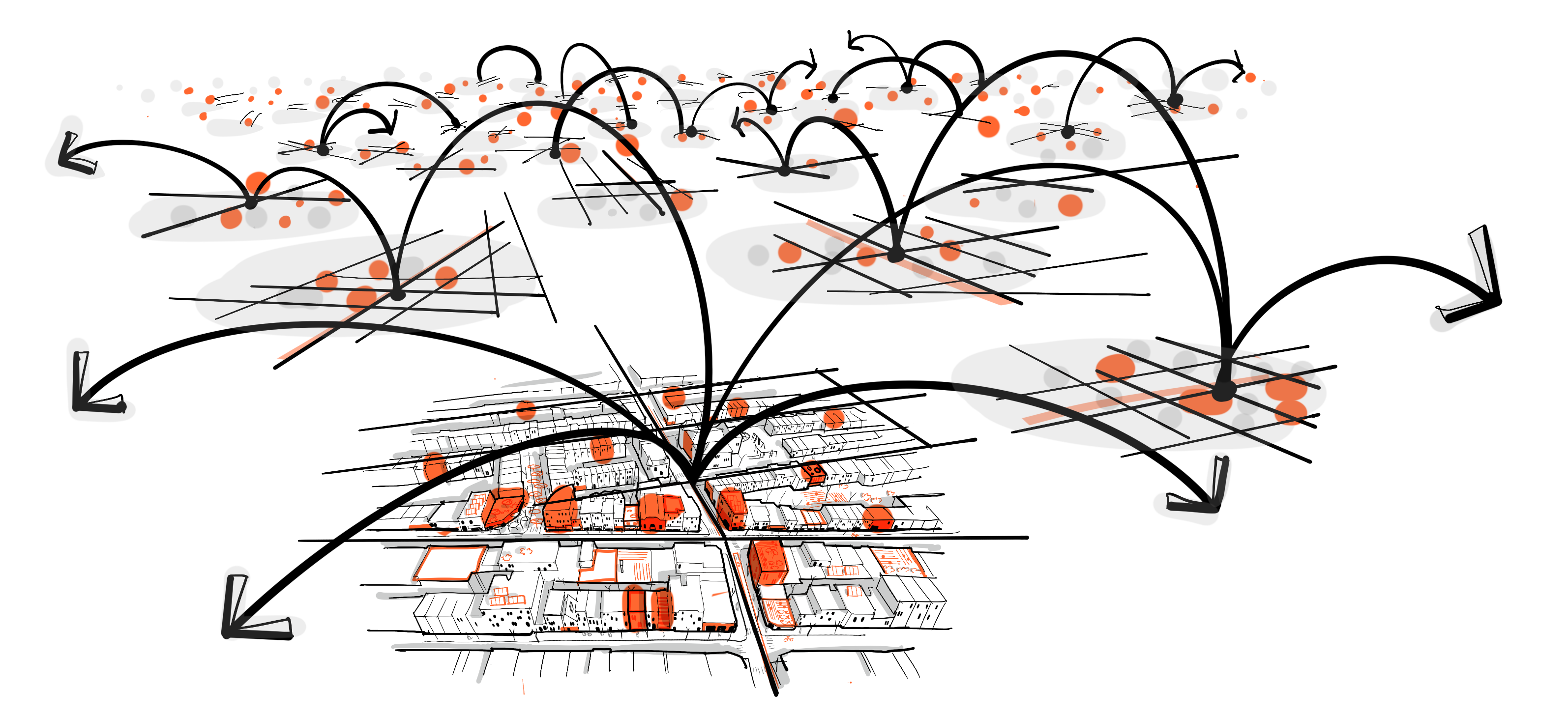

Building a Resilient New York City

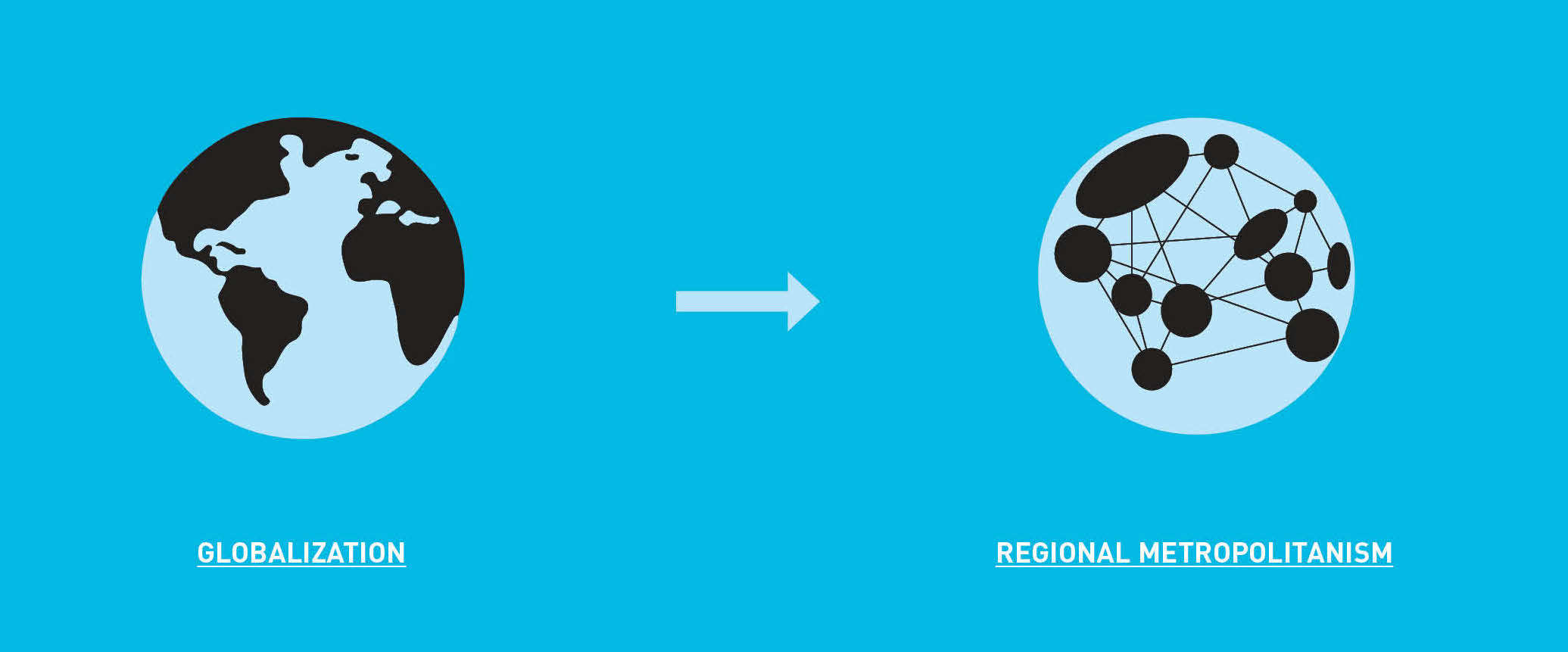

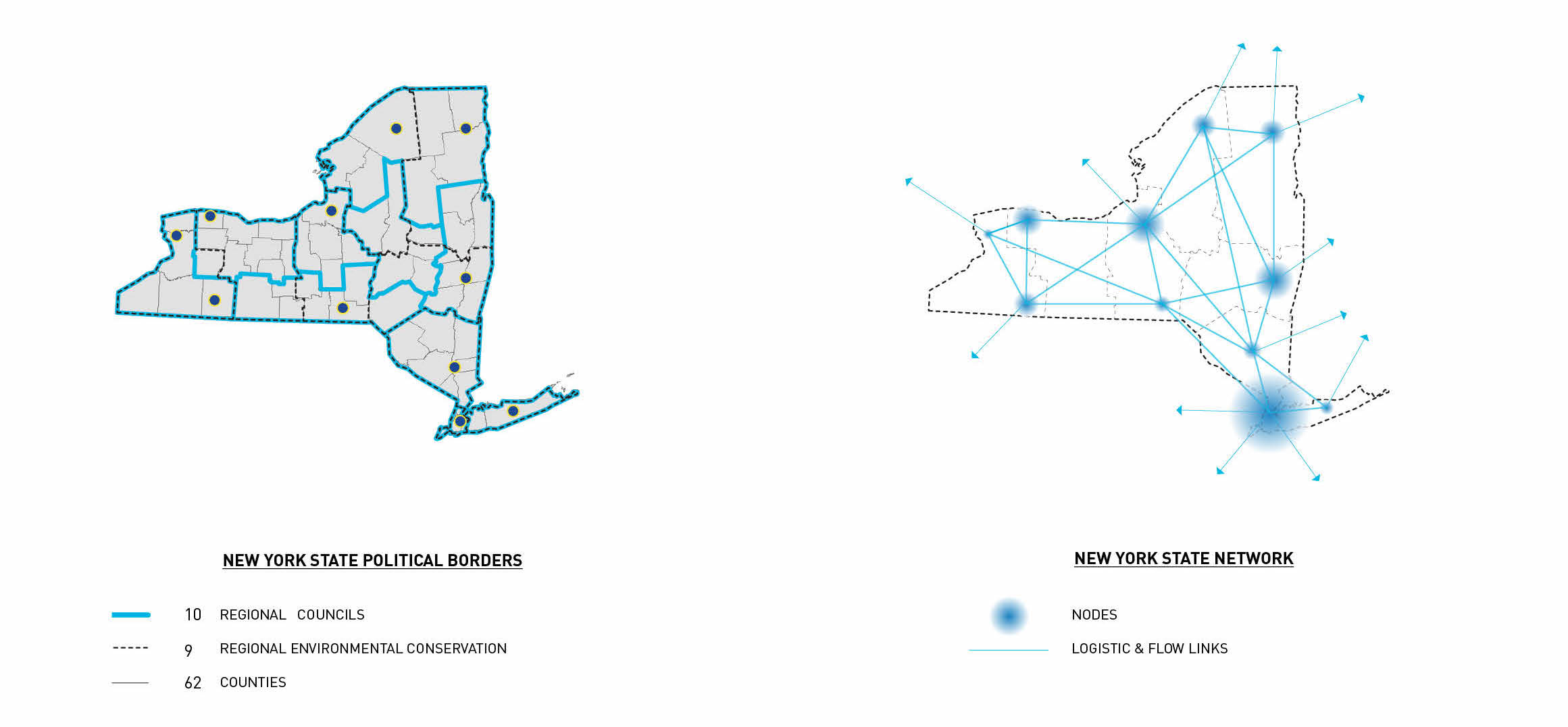

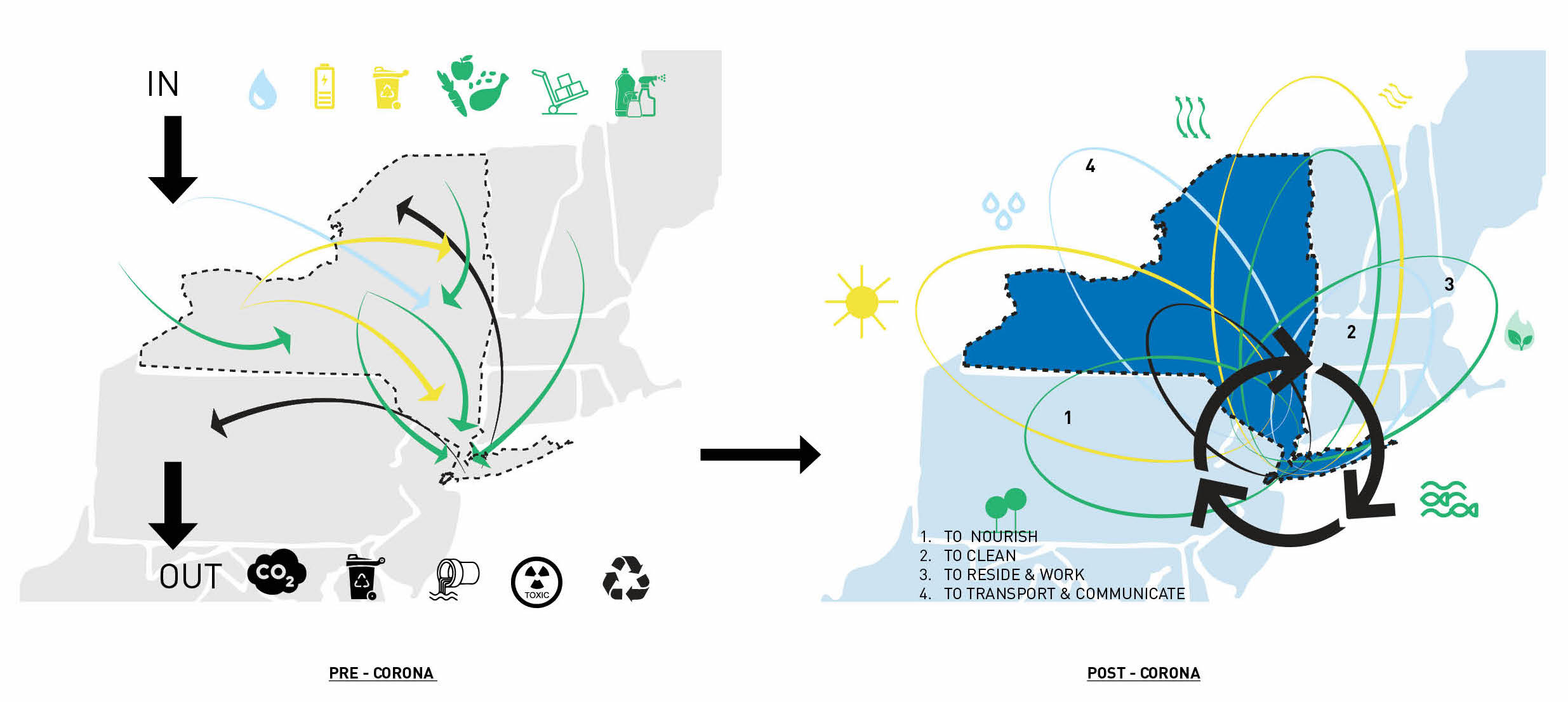

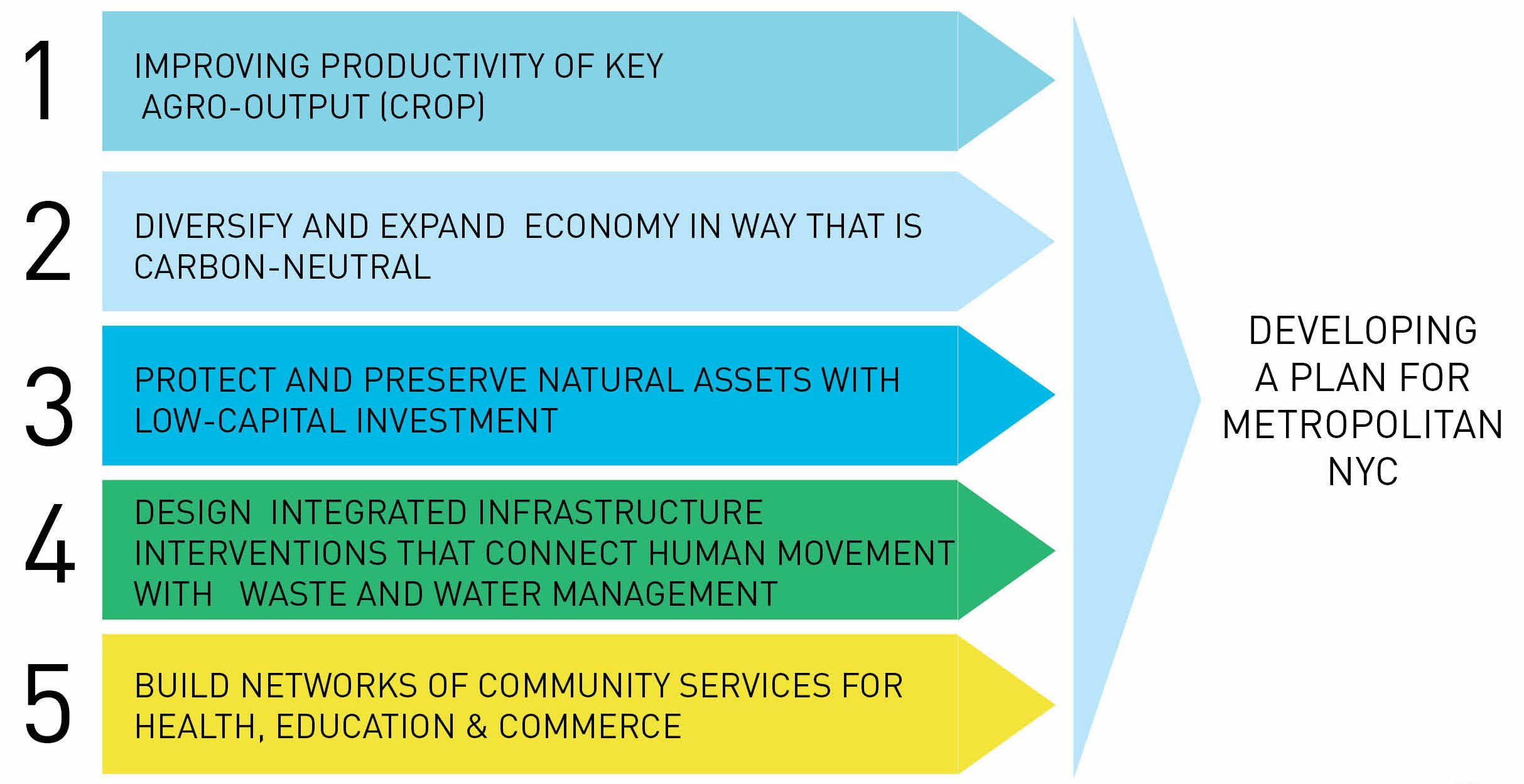

If the coronavirus kills globalization, what will replace it? We see a new age of regional metropolitanism dawning. The regions around Rome, Paris, Boston and Beijing have been experiencing greater and faster population increases than the traditional urban cores. Government policy in these regions has rebalanced itself to account for a new emerging territorial network of work, live, play and make NYC needs to follow suit.

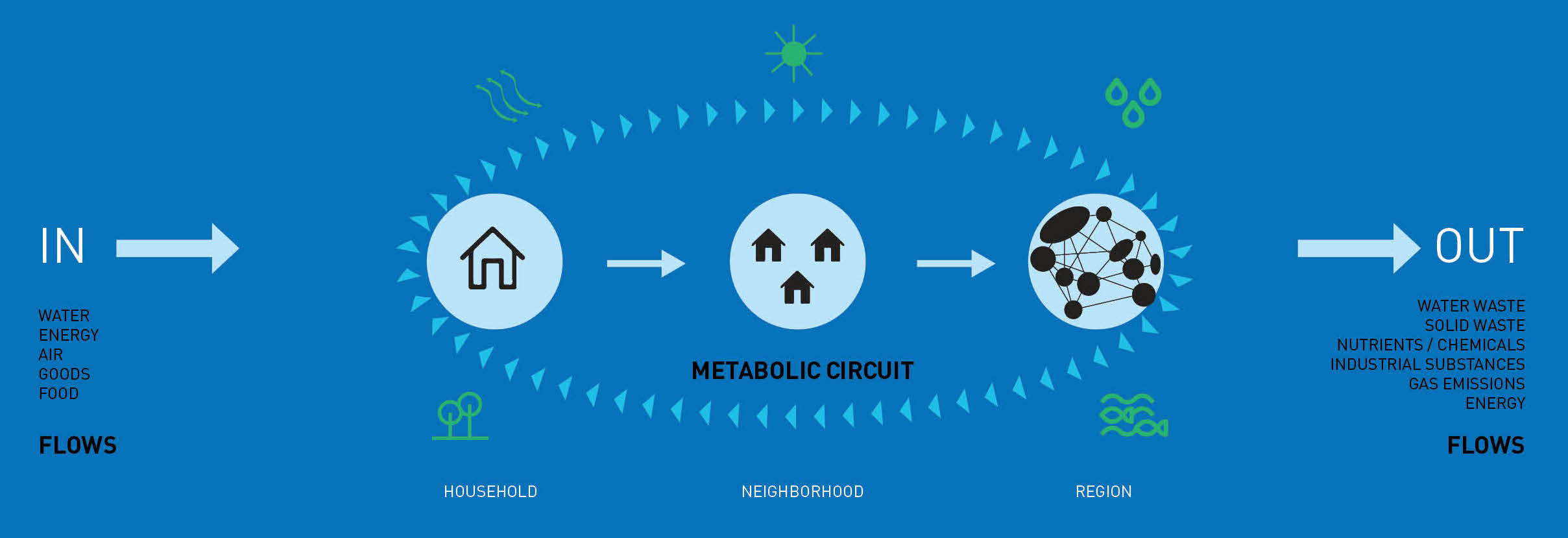

We think that the planning and design of regional metropolitan areas, such as that of NYC and its hinterlands, needs to be done in a much more rigorous way. The call to repatriate offshoring will meet the need to protect the natural assets of the countryside. Climate change will reveal the links between the surrounding regional environment and the metabolic demands of a neighborhood on water, waste and energy.

Planners will have to understand networking arrangements better in order to encourage the right scales of occupation, growth and openness. Politics will adapt to the realities of settlement patterns at different scales of dispersion and intensity.

We believe that design can serve as an effective tool to create new regional networks for cities like NYC so that we do more than just return to normal and instead build robust and resilient regions in the wake of the coronavirus.

Trends Affecting NYC

Population Dispersal

Population dispersal towards urban peripheries and rural hinterlands will intensify in a post-pandemic age.

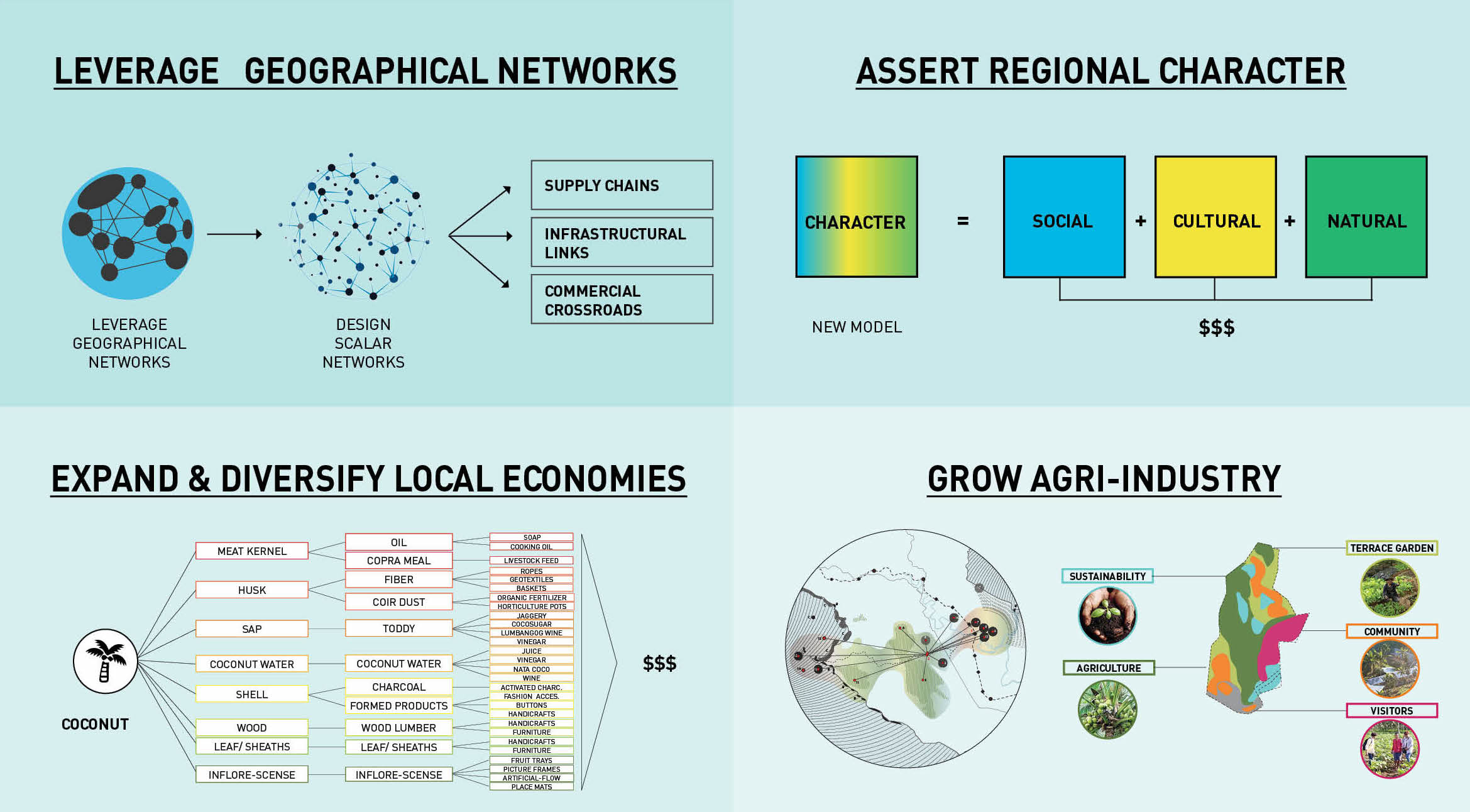

Reshoring

Reshoring creates opportunities for rural synergies between agriculture, manufacturing, and commerce.

@Homing

Housing and technology will converge creating a new work-live balance in the emerging rural metropolis.

Agri-Movement

Demand for locally grown food will require the strengthening of supply chains fortified with real-time data analysis.

Strategies for New York City

Leverage Geographical Networks:

Design networks that take advantage of the differences in scale between small, medium and large communities by fortifying supply chains, strengthening infrastructural links and creating commercial crossroads.

Assert Regional Character:

Capture the value of NY region’s social, cultural and natural assets through a strategy of monetized preservation.

Expand & Diversify Local Economies:

Increase value of local commodities through targeted R&D investments that build technical training opportunities & increase interaction between adjacent industries, a simple example is the coconut tree in the tropics. What are the opportunities for New York and regions around?

Grow Agri-Industry:

Take advantage of the socio-economic benefits of agriculture’s metabolic output through customized technology focused on the flows among soil, water, energy and waste

CAZA is a Brooklyn-based design studio working with SURBA, an urban think-tank dedicated to the improvement of planning, policy, and development through geographically well-informed data-driven analysis.

Microcosm: Creating Decentralized and Resilient Food Systems

The Covid-19 pandemic displayed a darker consequence of globalization. We saw insecurities related to food scarcity, travel standstills and logistics. A recent COVID Impact Survey conducted by the Brookings institute indicates that more than one in every five households is food insecure in the United States. New York City is the hardest hit part of the country, where 1 in every 4 New Yorkers were food insecure and addressing food insecurity was a central part to the pandemic response (Figure 1). Drone footages show endless lines of those waiting to pick up food from pantries or even grocery stores, bringing to light the cracks in the food system (Figure 2).

Figure 1 – Residents wait in a line outside a food pantry in Brooklyn during the COVID 19 pandemic. Due to high levels of unemployment, lines at the daily food pantry have been growing longer.

Figure 2 – In this April 1, 2020, photo, cars line up at a drive-thru food pantry at Woodland Mall in Grand Rapids, Mich. The National Guard helped distribute the food at the site, which was run by Feeding America West Michigan. The pantry is one of many set up after the coronavirus arrived in Michigan. (Neil Blake/The Grand Rapids Press via AP)

It was also especially apparent in developing countries like India, which implemented Stage-4 lockdowns resulting in a complete pause in essential supply chains underscored by hoarding, panic-buying and mass migrations. These situations throughout the world left those with lower incomes the most vulnerable during the pandemic – they lost their only source of income and lacked fundamental supplies – especially food (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – The underserved waiting in lines for packaged food amid COVID-19 pandemic, while maintaining social distance

This proposal aims to empower underprivileged communities in Indian cities by designing a system of self-sustainable micro-plantations within households — resulting in improved food security, better nutrition and greater economic stability.

Context

It is estimated that two-thirds of the Indian population will be living in cities by 2050, most of them below poverty lines. Following the 2008 recession and subsequent inflation, the urban poor were living on daily-wages, and spending 80% of their income on food, yet were chronically hungry. They were suffering from food insecurity and malnutrition – a situation laid bare by Covid-19.

While there are numerous organizations supporting temporary recoveries, ‘Microcosm’ sees the opportunity of a resilient self-sustaining strategy that creates immunity against future shocks and provides growth opportunities.

Microcosm aims to create self-sustainable micro-farming communities through the contextual and spatial design of plantations, development of farming kits, education, and outreach of farming techniques, and the creation of a barter support-system among the residents of the community.

Description and Implementation

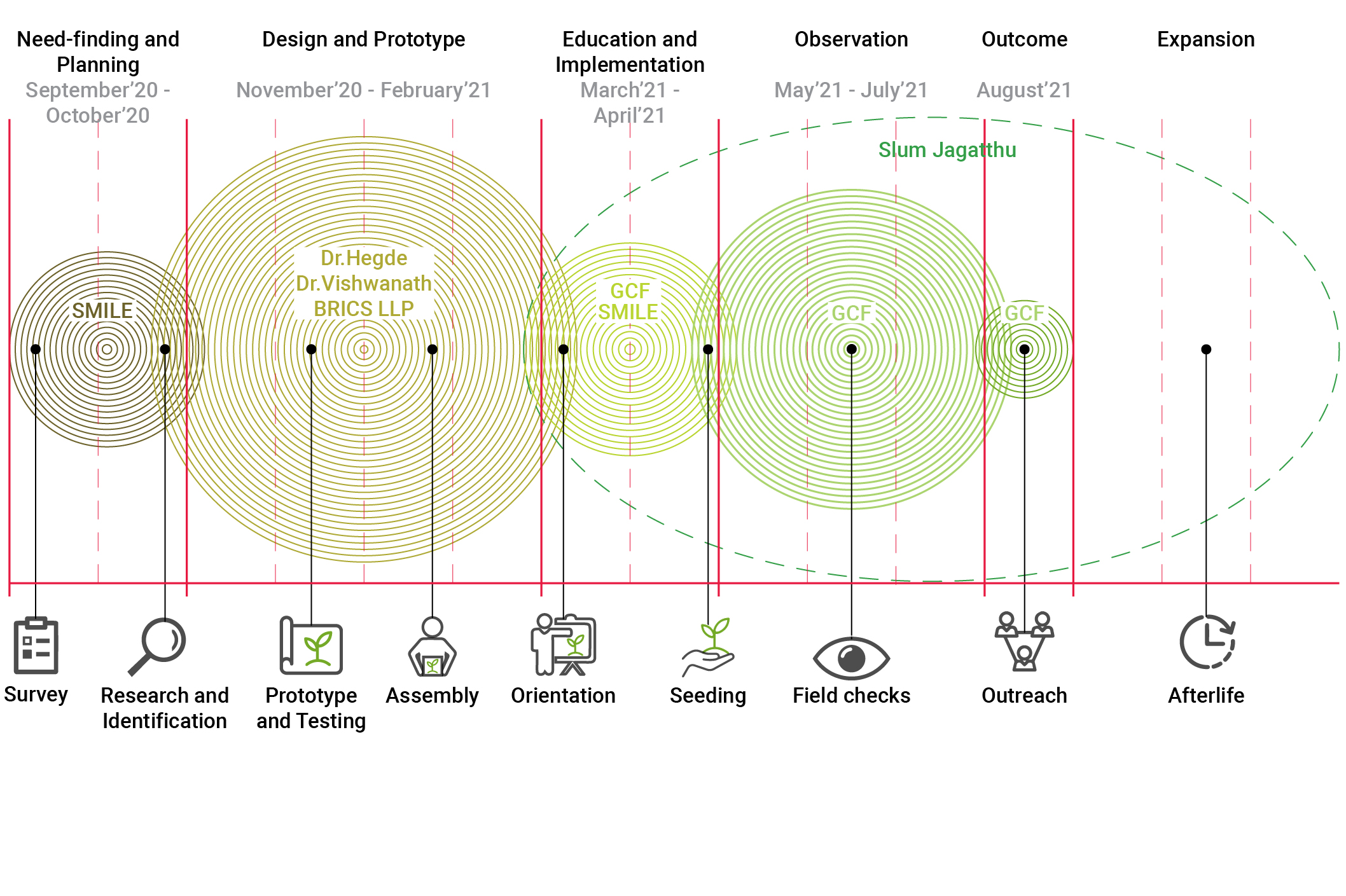

Figure 4 – Implementation process, and project timeline, illustrating the step by step scheme along with collaborators involved

To understand the context and establish the goals for a pilot intervention, it is important to undertake a survey and analyze existing socio-economic conditions and disaster management strategies (Figure 4). Developing collaborations with existing initiatives and not-for-profit organizations could help establish connection with these low income neighborhoods. A number of organizations in the five boroughs have been assisting communities to fight food shortage through community gardens and food pantries (Figure 5 and 6). This outreach to the community can play a pivotal role in establishing an initiative like Microcosm.

Figure 5 – Children of the Light Food Pantry arranges groceries for residents in New York City.

Photo: José A. Alvarado Jr. for The Intercept

Figure 6 – NYC’S Battery Urban Farm project spans one acre as the largest educational farm in Manhattan.

Photo: United States Department of Agriculture Website

The first step would be to establish sustainable subsistence-farming strategies and kits through spatial analysis, research and parametric prototyping and using the site specific parameters derived from the surveys and site study. One of the larger challenges faced during the proposal if this initiative would be a backlash from the local community —– It would be highly beneficial to collaborate with field experts and local members in the region who can be engaged to establish an effective and sustainable middle-ground between organic and commercial farming strategies, economically viable for the community. Sustainable practices could involve composting for manure generation or research of natural detergents for water recycling and hydroponics for space conservation can be implemented.

Educating the community about the methods and benefits of growing their own food and creating awareness about its nutritional and economic benefits is a key factor for the adoption of this methodology. This awareness can be spread through community workshops and campaigns. Assistance from experts and urban farming organizations that are already promoting and practicing sustainable urban farming would be required from the time of sowing to reaping the produce of the first crop cycle. This entire process (Figure 4), if documented and published across media with presence in communities of similar standing can help amplify the initiatives outreach and the importance of urban farming among other neighborhoods and communities.

This proposal can be envisioned as a reflective experience, portraying the impact of the project on the community, prototype design for public use and its vital role in sustaining the community through other future shocks. The ultimate aim is to inspire individuals, communities and institutions about the advantages of in-situ farming and encourage their transition to growing their own food.

Benefits and Future

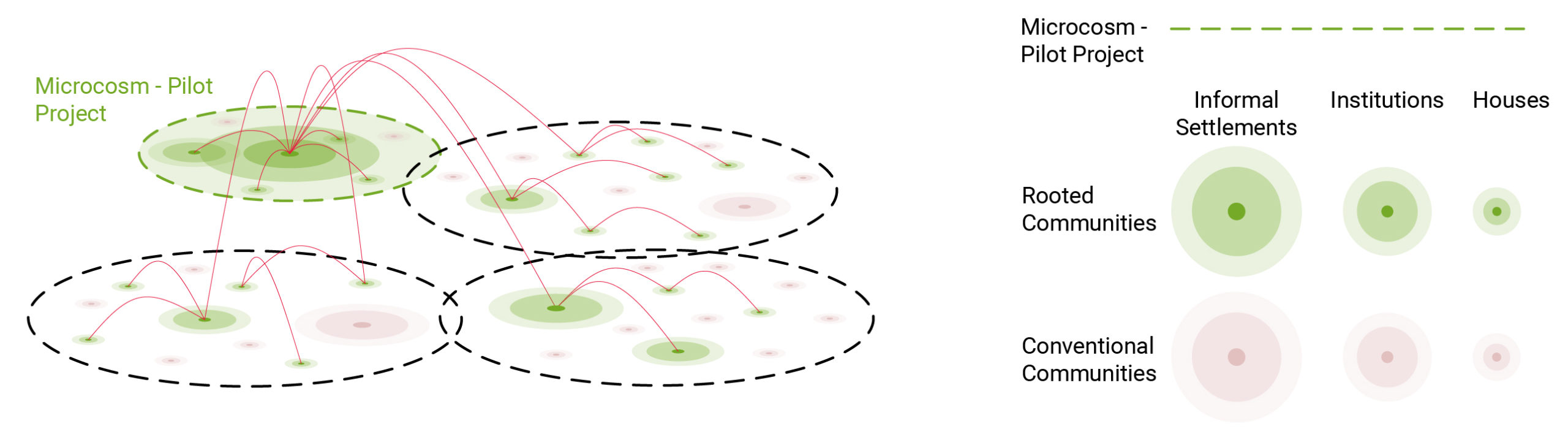

Figure 7 – Design Implication, illustrating the project afterlife and growth into communities, neighborhoods and organizations in the city and other cities.

“We’re committed to helping countries…be better prepared when risks materialize, one of them being food security.” – World Bank Apr.2020

Over time, skills acquired during this project would provide a platform for new business opportunities to sell produce at local markets and collaborate with neighboring households to set-up micro-garden systems in exchange for additional income and social capital credits. The proposal has the ability to spark a movement that can instigate a nation-wide slum development, securing permanence to residents in exchange for their services to the city.

Health and Cities – Social and Humanitarian Impacts

“End hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.” Sustainable Development Goal 2: Zero Hunger

In conclusion, this proposal focuses on empowering excluded and vulnerable groups by introducing a system of self-sustainable urban agriculture based on shared enterprise, creating communities that are resistant to natural and man-made crises, by ensuring fresh produce all year. Apart from reducing starvation, achieving food security, improving nutrition and economic conditions, these micro-gardens also lead to a healthier living environment. Although the demographic and socio-economic conditions of India are very different, food insecurity is a global issue – the proposal engages vulnerable communities and this could be applicable to how New York can create a decentralized and resilient food system.