In cities like NYC, affordable housing is in short supply and vulnerable populations face a multitude of roadblocks when trying to find places that are affordable, accessible, and safe—this pandemic has further highlighted this growing inequality. These proposals address the needs of people experiencing homelessness during this time, finding ways to safely connect through communal activities during quarantine, and the power of affordable housing as a means of recovery. Scroll to read all 7 proposals.

Houselets: Utilizing Urban Infrastructure to Create Housing for People Experiencing Homelessness

The Housing Livability Index: Questioning the NYC Housing Market

An Analysis of COVID Impact Based on Location

Responses Continued ↓

People over Property: Affordable Housing as the Cornerstone of Systemic Change by Deborah Morris

The Housing Livability Index: Questioning the NYC Housing Market by Ankita Nalavade

An Analysis of COVID Impact Based on Location by Elliot Scarangello

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Urban Design Forum launched City Life After Coronavirus, a digital program convening Fellows and international experts to document global responses to the current crisis and to strategize a road to recovery for New York City. In April, we released a Call for Ideas to our network soliciting a broad range of submissions that envision how urban planning and design should change in the wake of Covid-19 as we strive to build a more just city for all New Yorkers. We are featuring some of the most compelling ideas in a series of reflections and proposals about diverse topics like education, community engagement, and mobility. Explore the full Gallery of Urban Ideas here.

Reimagining Shelter

Marvel Architects recently performed a CPSD Masterplan on the 30th Street Shelter in New York City for DDC, where four primary principles in homeless shelter design were developed, and are presently being employed.

Homeless shelters are an integral part of NYC’s social infrastructure. At best, they provide a safe and effective transition-point services for New Yorkers in crisis to find permanent housing solutions. At their worst, they exacerbate despair and promote victimization, becoming places to avoid for fear of safety, places which incite community outrage.

Shelters by design are dense temporary housing models that provide access to a safe bed, food, and health and social services. Best practices pre-pandemic focused on increased interaction in social spaces to encourage self-supporting inspirational environments, where clients are active stakeholders in their own success. Caseworker offices are often clustered together to ensure maximum interaction between client and social worker. Dining and lounge areas encourage close social interactions.

But these same shelter design elements have proved challenging during the pandemic. Some shelters have been compelled to relocate their populations to hotels. This is made possible due to the decline in hotel room usage. This model has helped ensure client safety from the coronavirus, but runs counter to City objectives to end hotel sites, as stated in the 2017 “Turning the Tide Against Homelessness in NYC,” and in the 2019 “Journey Home,” the six-point action plan to end street homelessness.

It is expected due to coronavirus and its related economic recession, that the already rising homeless population will spike further. To avoid the need for adding an excessive amount of new shelters, it is imperative that existing shelters improve their efficacy to reduce the duration of client stays, by effectively transitioning clients into permanent housing sooner.

We have a legal and ethical obligation to ensure the marginalized homeless population is not adversely affected by coronavirus more than it already has been. Housing is always the goal, but the interim emergency step of shelter is essential to reduce the homelessness crisis.

In thinking of Urban Design Forum’s “City Life After Coronavirus,” we first need strategies for safely repopulating homeless shelters while pandemic health concerns persist. It is imperative these are cost effective and functional measures. Beyond this immediate need, we know whenever public dollars are spent on shelters, there is an opportunity and moral obligation to stretch those dollars.

Too often shelter improvements have been piecemeal responses to emergencies, without considering, nor helping, resolve longer term goals. To this end we offer the following design guidelines outline, organized under four essential shelter design principles, which address the new concerns for sanitation and health, while also promoting best new practices for shelter design. Marvel Architects is already working with several of our clients to pilot these changes.

Multiple separate entries allow for minimum overlap with clients entering and leaving the shelter. Providing outdoor plantings, furniture, and markings can ensure social distancing while waiting.

For and from Clients, Perceived and Actual

- Provide one-way traffic entrances where possible. This ensures minimum overlap with clients waiting for security and clients leaving the shelter facility, improving both health and security.

- Reconsider admission timing sequences and spaces to eliminate exterior lines on sidewalk. Where possible, provide outdoor plantings, furniture, and markings to ensure social distancing.

- Dedicate secure and private outdoor client spaces for improved health. This space can be used for recreation, as well as setting up safe caseworker meeting spaces.

- Incorporate touch-less client entry and digital census technologies to ensure less time and interaction between staff and client.

Reduce Barriers to Success, Increase Shelter Efficiency

- Provide a mix of spaces, including potential quarantine spaces and Covid-19 testing services.

- Improvement and expansion in shelter services and their delivery including housing, legal, and employment services, health and wellness services, and computer and educational services.

- Where possible, encourage the use of technologies such as video calls through tablets to provide safe access to case workers. Streamline appointments and routinely clean all equipment used during interaction.

- Create a safe way for clients to interact with caseworkers. Larger waiting areas for safe social distancing, and private meeting rooms. This ensures the case worker’s office where they spend most time is not where the interaction with a client happens. Where possible, located these meeting rooms close to windows and in places with good ventilation. Alternatively, use 6’ table sizes or plexiglass screens to separate.

- Reschedule the dining system timing into additional phases, limiting the number of people in dining rooms at one time.

Design for Dignity

Change Mindsets

- Promote hygienic practices by providing sanitation stations, Infrared Fever Screening Systems (IFSS), and bold signage and communications employing best practices in health precautions such as social distancing floor markings.

- Increase seating spacing in public areas, limit number of beds per dorm and provide health and privacy screens

- Improve Architectural finishes to be anti-microbial. Employ touch-less features at doors, elevators, lighting, and plumbing fixtures.

- Increase the amount and types of cleaning and ensure all cleaning materials are anti-bacterial. Be sure bathrooms are well-stocked with soap, and order adequate anti-viral cleaning supplies in the event of a shortage.

Reduce Stigma, and Encourage Altruism

- Design outdoor areas with flexible types of seating and appropriate seating groups that encourage social distancing.

- Improve exterior building appearance and provide information about best practices being enforced within the shelter. Open communication and good facility maintenance helps build support from the community.

- Provide opportunities for partnerships and volunteering though technology and safe in-person activities like planting vegetable gardens and dog runs.

- Become a neighborhood asset, serving as a resource for whatever current needs the community might have.

Marvel Architects is a solutions-driven design practice that integrates context and nature into every project, meeting each design challenge by listening to its surroundings. With offices in New York and San Juan, Marvel is an international firm dedicated to creativity and diversity. From the New Jersey Institute of Technology to St. Ann’s Warehouse, the team has pioneered an entrepreneurial approach to architecture and place-making that has been recognized by over 125 industry design awards including the AIA’s highest honors.

Healthier Models for Urban Living

The pandemic has prompted a healthy debate and speculation about the longer term impacts on the city and urban density in facilitating the spread of the virus. Some suggest a move back to the suburbs will be inevitable. Putting aside the macro level reasons (e.g. cities’ inherent advantages with regard to sustainability, equity, the limited mobility capacity in the suburbs etc.) this is a narrow choice that is limited. For those who are able to contemplate single family living in Metropolitan area suburbs, the cost is high, and the inventory is limited. Outside of these options are a limited range of other multi-family formats. In recent years, five or six story wood-frame buildings organized around elevators and double-loaded corridors have become increasingly common in inner ring suburbs. For those who seek to remain in the City, multi-family options are similarly limited largely to elevator buildings with apartments lining both sides of windowless corridors.

The predicament raises a range of questions. Might recent events open up the market to lower height/high-density models that do not depend on the shared circulation elements (like elevators, crowded shared stairs, double loaded corridors) that inhibit contact-wary New Yorkers from getting to the sunshine and outside air of New York’s streets and parks, and restrict them to the confines of their apartments? Are there alternate typologies that can achieve comparable densities that may now look more attractive relative to the current models for urban living? How can denser urban housing be designed to provide some breathing space in the daily interactions that people have been conditioned to fear in the course of the lockdown? Does the crisis present an opportunity to give a more considered look at different, and potentially healthier models for urban living?

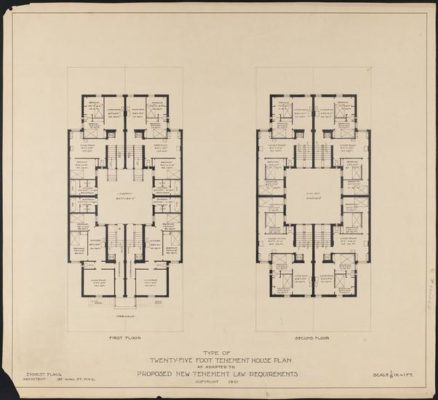

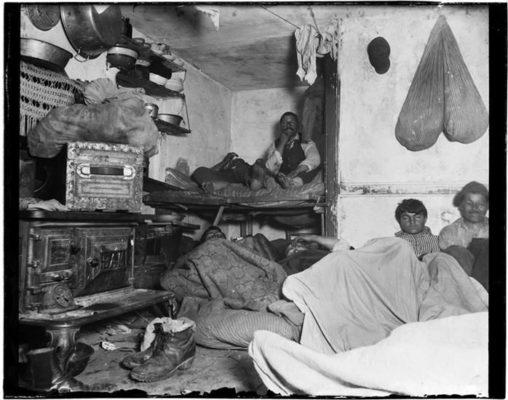

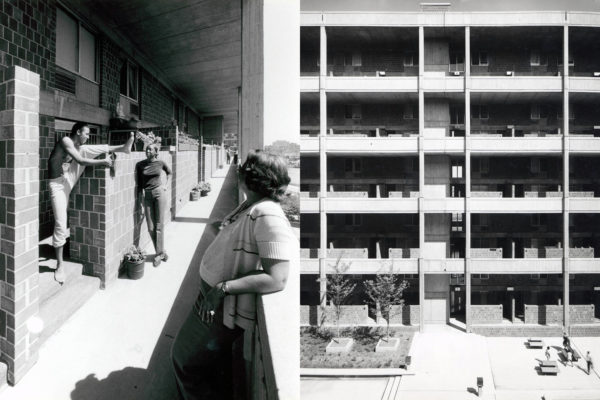

The adoption of many of New York’s most enduring and prevalent housing types over the last century were driven by a response to health and hygiene concerns. At the beginning of the 20th century, for instance the new law tenement was adopted as the result of legislation that was in turn a response to a lengthy campaign by muckracking journalists and urban reformers like Jacob Riis, who linked the lack of light and air to the spread of disease. Fifty years later, the “towers in the park” model was adopted to provide a relief to overcrowding in post-war cities by offering light and air while as well as increased densities.

This model was not only take up by figures like the prolific Robert Moses for New York City’s public housing program, but also by cities and developers throughout the Metropolitan area and the U.S. Both of these models originated with innovations that were crafted years before, but did not achieve wider adoption until a shift in underlying conditions and/or public sentiments prompted a change in regulatory framework or a response by the development community. Will the pandemic cause a sufficient shift in attitudes that it will spur healthier models for urban living?

If so what are the elements that might be called into question? Will this spur an acknowledgement by city-dwellers and developers of the drawbacks of current prototypes? Are there affordable typologies that do not rely on an elevators and double-loaded corridors, but instead, provide direct access to the outdoors and the public realm?

To illustrate the possibilities, we have developed three scenarios for a typical New York City block. The two midblock scenarios propose alternative typologies that challenge current development norms. While these alternative typologies may at first appear unlikely for New York, both in fact have roots in a proud, but sometimes overlooked New York City tradition of experimentation and innovation in housing.

All three scenarios balance the need to prioritize health and wellness and commercial viability. And while the issues raised by the pandemic were the impetus for the investigations, we believe this moment brings with it an obligation to address larger changes – in demographics, living patterns, and the environment, as well.

Farewell to Hallway Claustrophobia: New Life for the Single-Loaded Corridor

The single-loaded corridor housing typology introduces natural light and ventilation to the apartments, and to the circulation corridor, as a way to integrate some of the most attractive and healthful qualities of the detached home into apartment buildings. To achieve the efficiencies of the typical double-loaded corridor, single-loaded corridors are proposed on every other floor, in conjunction with through-floor duplex apartments, or stacked ‘maisonettes’ (commonly used French term for “small house”).

More commonly found in Europe, the single-loaded corridor with duplexes has also been used in notable projects in New York City, such as Riverbend in Harlem, designed by Davis Brody which opened in 1967, and the Eastwood and Westview apartments on Roosevelt Island, designed by Sert Jackson, which opened in the mid-1970s.

Since the 1980’s, the introduction of accessibility codes and changes in demographics appeared to eliminate the advantages of stacked maisonettes. The Americans with Disabilities Act, passed in 1991, required a bedroom and full bath on the entry level, increasing the size of the upper level floor plates, and putting the type seemingly at odds with the trend toward smaller households.

We believe that revisiting stacked maisonettes in the post-COVID era may suggest new relevance for this typology, accommodating non-traditional households and new patterns of living and working from home. Entry-level bedrooms can accommodate live-in caregivers, elderly parents, and extended families, etc. Larger floor plates on the upper level can allow for home offices, or more flexibility to accommodate unrelated roommates. The single-loaded corridor can also be combined with through-floor simplex apartments with open or closed windowed corridors for small apartments for one or two people and a common interior space or terrace on each floor.

Call Outs:

- Single-loaded corridor allows light and air to the units and to the common hallway

- Visibility of the corridor from the raised outdoor entrance patio, from the kitchen, and from the internal stair to the upper duplex level allow connections between neighbors and promote safety, while enhancing a sense of community

- Greater connection to neighbors and the outdoors, provision of private and semi-private terraces, greater variety of double- and single-story circulation spaces, encourage inhabitants to “collectively watch out for one another without making a conscious effort”

- Semi-open egress stairs with light and air, where one can see and be seen, are more attractive and thus more likely to be used, fostering connections with neighbors, while reducing the passenger load on elevators

- Apartment Entrance ramps along the corridor raise the ground floor above the circulation space, providing a transition between the semi-public corridor and the semi-private entrance patios.

- Integrating double-height private and semi-private outdoor spaces introduces an economical way to make the apartments feel larger and provide a richer sequence between the corridor and the home.

- Entry Level bedroom can serve as a home office if not needed for an elderly parent or handicapped family member.

- Floor-through living: Lower and upper levels both allow for natural cross-ventilation and two sources of daylight and views

- Larger upper level floor plate accommodates home offices and can be fitted with kitchenettes as studio apartments within a group of units with flexible access

- Achieves 85%-90% efficiency depending on the number of additional units/lofts on the open side of the corridor

2. Stepping off: Reducing Elevator Overload

The other approach is to reduce the number of apartments per elevator. While limiting the number of apartments per floor is a hallmark of housing design in places like Europe, Russia and China, the drive for efficiency has typically kept the number of apartments per floor at 10 or more in the New York, a major driver in the length and oppressiveness that often associated with circulation corridors in New York City apartment buildings. While the fear of overcrowded elevators and elevator lobbies may pass with the pandemic, this has never been one of the more humane aspects of New York City apartment living.

This model organizes five apartments around a donut circulation scheme, allowing for floor-through units and introducing natural light to the elevator lobby – always one of the more fraught spaces for apartment dwellers. Designed for a common 100’x100′ lot NYC parcel. While reducing the number of units sharing an elevator core may seem antithetical to the never ending drive for efficiency in New York City apartment design, this model, which could be envisioned as a basic building block for redevelopment on a larger scale also has roots in New York residential design tradition, most notably the magnificent London Terrace Towers in Chelsea.

Key Features:

- Minimize number of units per floor

- Generous elevator lobby opens out for light and fresh air

- Wider corridors together with entry recesses provide additional areas for passing neighbors.

- Dead ends are minimized to provide multiple directions of circulation for alternative routes

- Directional entry vestibules for ingress and egress

- Multiple lobby entrances to larger buildings for optional circulation route alternatives

- Clear visibility of stairways from building entrances for alternative vertical circulation possibilities to reduce elevator capacities and encourage physical activity

- Floor-through units

- Donut circulation eliminates dead-end corridors

- Spacious entry lobbies to allow for wider areas of circulation, allowing public spaces to function as places for gathering and collaboration.

- Efficiency: 75%

First Steps Forward: Incremental Improvements to the Typical New York City Apartment Building

The third scenario, using a 100’200’ end block site demonstrates how the concepts included in the two alternative typologies can easily be incorporated within the conventions of a typical New York City development scenario:

- Introducing a second core to reduce the number of apartments sharing an elevator,

- Providing choices for apartment dwellers to reconfigure their needs for space as their circumstances and family structure evolve,

- Bringing natural light and air to the circulation corridor, and

- Improving access to daylight and cross-ventilation in the apartments while allowing for more generous private outdoor space and rooftop gardens that can help foster a resilient food system.

Founded in 1981 in New York City, Perkins Eastman is a global architecture firm that has grown to include 1,000 employees working out of a combined 17 interdisciplinary offices around the world. From education and healthcare to mixed-use and transit-oriented developments, we design for a sustainable and resilient future, and to enhance the human experience through the built environment.

Credits:

Perkins Eastman Team: Eric C.Y. Fang, Ted Liebman, Joseph DesRosier, Frank Zimmerman, Jahaan Scipio, with Dan Heyden/MHG Architects

Un-designing Isolation: New Forms of Living

How do we retrofit or transform these environments to perform and serve diverse populations now that many people’s living and movement patterns have been drastically changed, with many confined much more to their immediate homes? These new patterns we believe will have a lasting impact. Social isolation has been an issue amongst many low income, elderly and multi-abled groups before COVID-19.

One thing that needs to be re-imagined is our relationship to public and private space – where these spaces are, and what form they take. How can this relationship be rethought in certain contexts? For one, we think that if folks can’t get to the public space, then the public space should be brought to those who need it. We have three projects that we feel are underscored by this crisis to unpack this issue at three different scales.

1) Side by Side

1) Side by Side

Cleveland, Ohio (2019-ongoing)

mixed-use accesible housing

grand prize, ZeroThreshold design competition

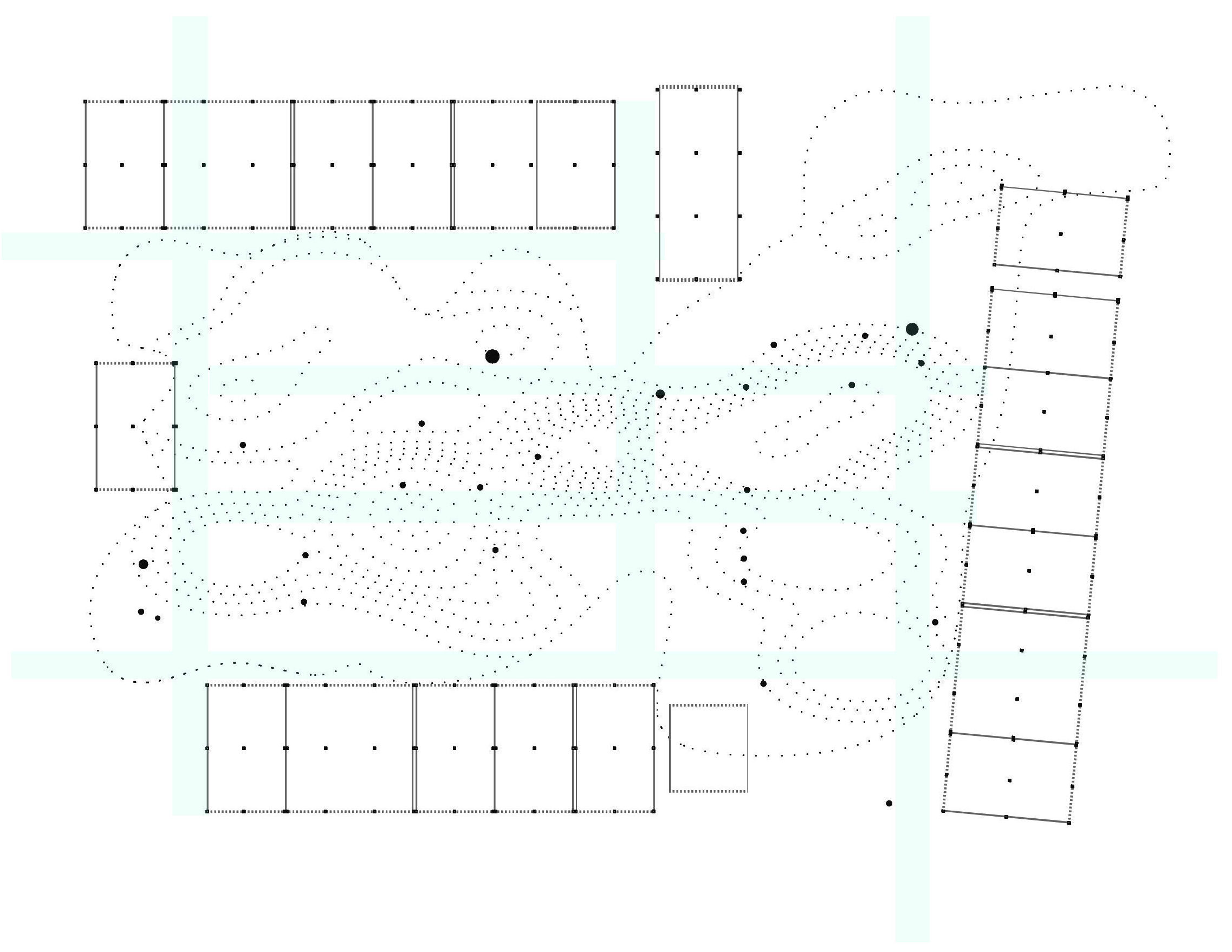

We start with a new form of mid-density housing which is imagined as an intergenerational, multi-abled living prototype that can connect to underused lots to form public amenities. The potential for this cooperative, semi-public / private model to aid public health in the post COVID-19 realm has underscored the urgency for such a type to be explored further.

SIDE by SIDE proposes an accessible urban prototype that incorporates communal cooking, gardens, and learning. Designed for inter-generational living, this project utilizes the prototype’s concept to transform an empty double lot and adjacent vacant lot into a mixed-use project designed to combat social isolation and provide an innovative new accessible living typology.

Substandard housing, lack of access to green space, and lack of social connectedness affects a wide variety of neighborhoods and demographics, including Old Brooklyn. Rather than tackle these issues in isolation, SIDE by SIDE offers a holistic design to address and improve accessibility and community-based issues faced by both the alter-abled and able-bodied alike.

The siting of this prototype – three lots located at the transition between the neighborhood scale and the retail/light industrial scale offers an opportunity to bridge the two and bring people together. These urban “edges”, common in many cities, become the point of departure of the project’s two primary components: 1) the community park/semi-public zone, and 2) the mixed-use living building with rear private garden.

2) Back-Lot Urbanism

Newburgh, New York (2018 -)

A concept of semi-communal infrastructure that corresponds with typical back-yard configurations in a diversity of urban/suburban settings. For post COVID-19 living, the potential for neighbor-to-neighbor infrastructures such as this might take the place of regular outings to restaurants and bars – and again, help to combat social isolation of the elderly and less mobile. This speculative exploration as part of ongoing research which seeks to unlock untapped architectural potential in the Hudson Valley at multiple scales. Newburgh, NY has a contained urban center which acts as a microcosm of urban blight affecting much larger cities such as Detroit or Buffalo. However, decades of economic de-investment have recently yielded to signs of urban renewal and experimentation.

Back-lot urbanism attempts to exploit the latent architectural, economic, and social potential of the tree-filled interior blocks that make-up the majority of the residential urban core. A partially shared infrastructure of raised platforms could serve as a space for communal programs, such as cooking spaces for both residents or food-tourism. Access points to the street frontage could provide some presence on the front lots. The proposal situates itself within the challenging, but evolving landscape of collaborative investment and architectural language at the scale of the block and neighborhood.

Back-lot urbanism attempts to exploit the latent architectural, economic, and social potential of the tree-filled interior blocks that make-up the majority of the residential urban core. A partially shared infrastructure of raised platforms could serve as a space for communal programs, such as cooking spaces for both residents or food-tourism. Access points to the street frontage could provide some presence on the front lots. The proposal situates itself within the challenging, but evolving landscape of collaborative investment and architectural language at the scale of the block and neighborhood.

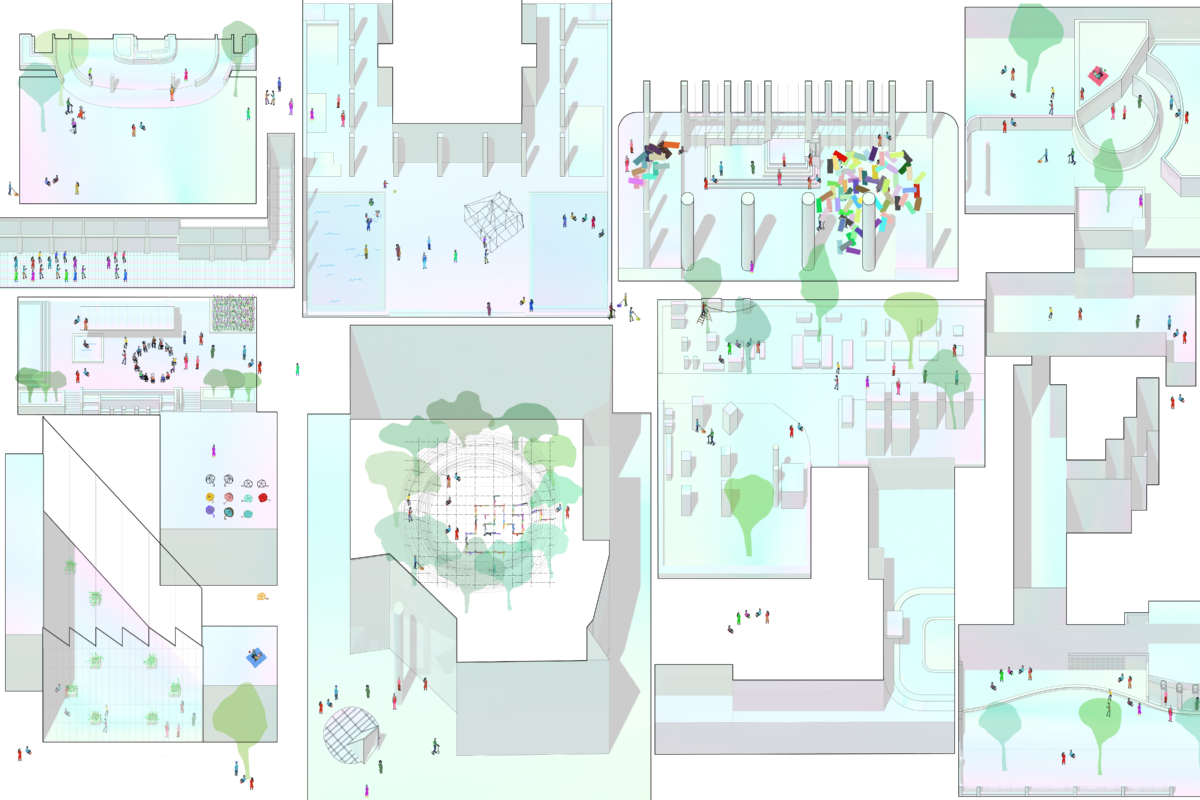

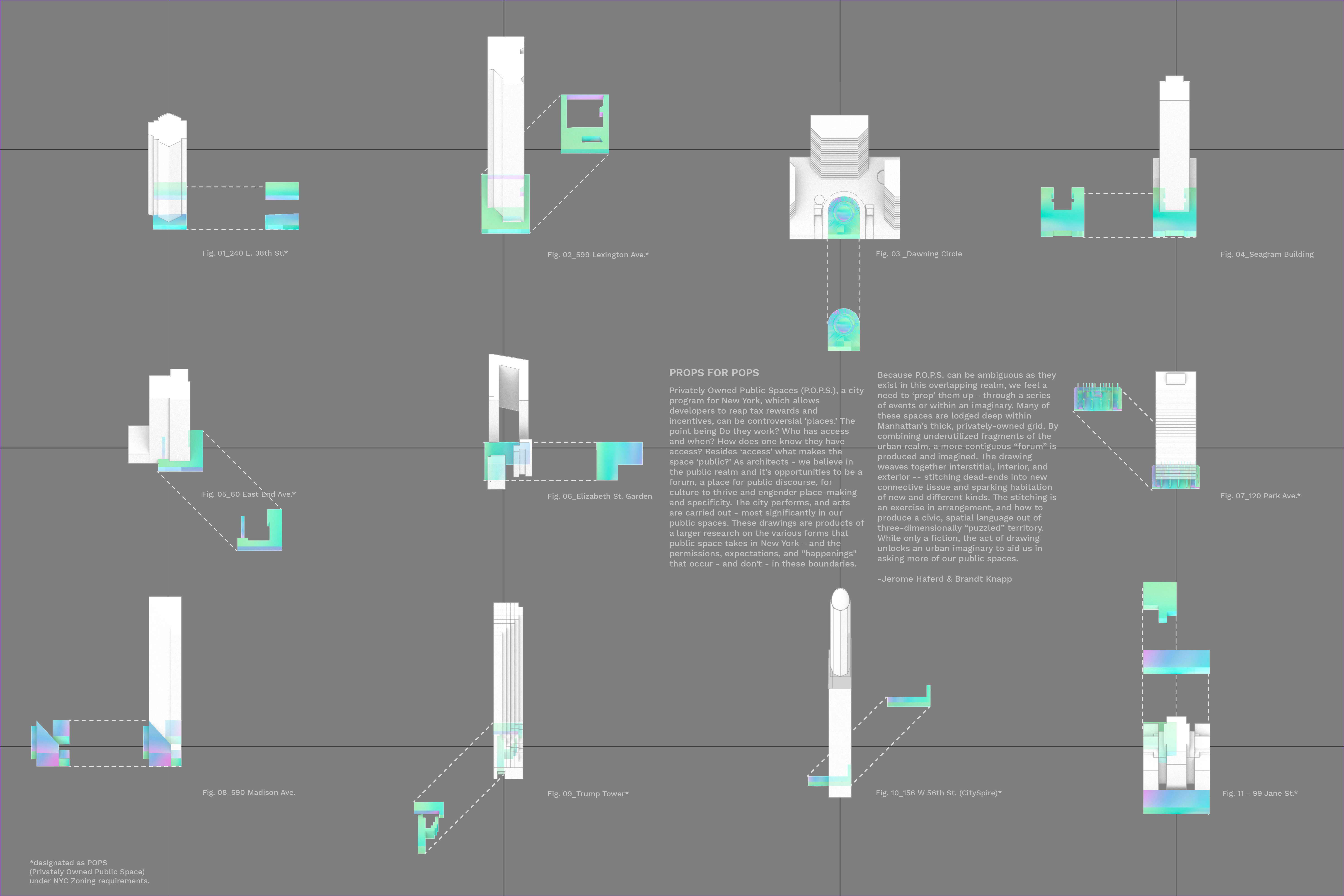

3) Props for P.O.P.S

New York, NY (2018 – ongoing)

publication research / site-specific performance

Finally, our urban “public” spaces will need to be re-imagined. Many of these spaces have been underutilized and undeserving the people for decades. Our re-imagining of various fragmented and underutilized public and semi-public New York spaces as a more continuous civic realm might actually go from fiction to reality in a post COVID-19 paradigm, as city streets are reconsidered and space for safely gathering and eating in groups will require larger, re-designed public fabric.

This project is concieved of as an architectural response to the question of critical forms and spaces of performance today.

Props for P.O.P.S. are a set of instructions for producing flash-architecture in ‘public’ space. Within the context of an ever-increasing number of ‘sanctioned’ performance spaces in cities like New York, this project aims to question and challenge the expectations of these spaces and their permissions, while also questioning notions of the public and “public” space in the city.

The instructions are generated for and by specific sites, each a type of “privately owned public space”. The performance is a collective act to produce a topographic ‘drawing’ that will unfold through the movement and sharing of participants. Using the “stuff” of the city – a scarf, an umbrella, a yoga mat – the ground is temporarily redrawn and transformed by a new terrain of shared/gifted materials. Misreading of the instructions is expected, even encouraged.

BRANDT : HAFERD is a Harlem-based architecture and design studio led by Jerome W Haferd & K Brandt Knapp. Their body of work includes academic research and a range of built projects – from the domestic to the workplace to the urban – that challenge the limits of practice. Haferd and Knapp were winners of the inaugural 2012 Folly competition held by the Architectural League of New York and Socrates Sculpture Park. Their 2015 installation, caesura, at Harlem’s Marcus Garvey Park was a collaboration with artist Jessica Feldman, and supported by grants, the NYC Parks and local organizations. The studio recently won the 2019 Zero Threshold competition for barrier-free housing with their project Side by Side, and are 2020 AIA New Practices New York recipients. They work with private clients, institutions, and city governments.

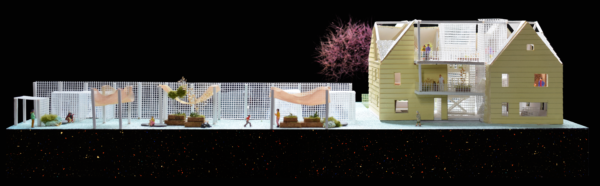

Houselets: Utilizing Urban Infrastructure to Create Housing for People Experiencing Homelessness

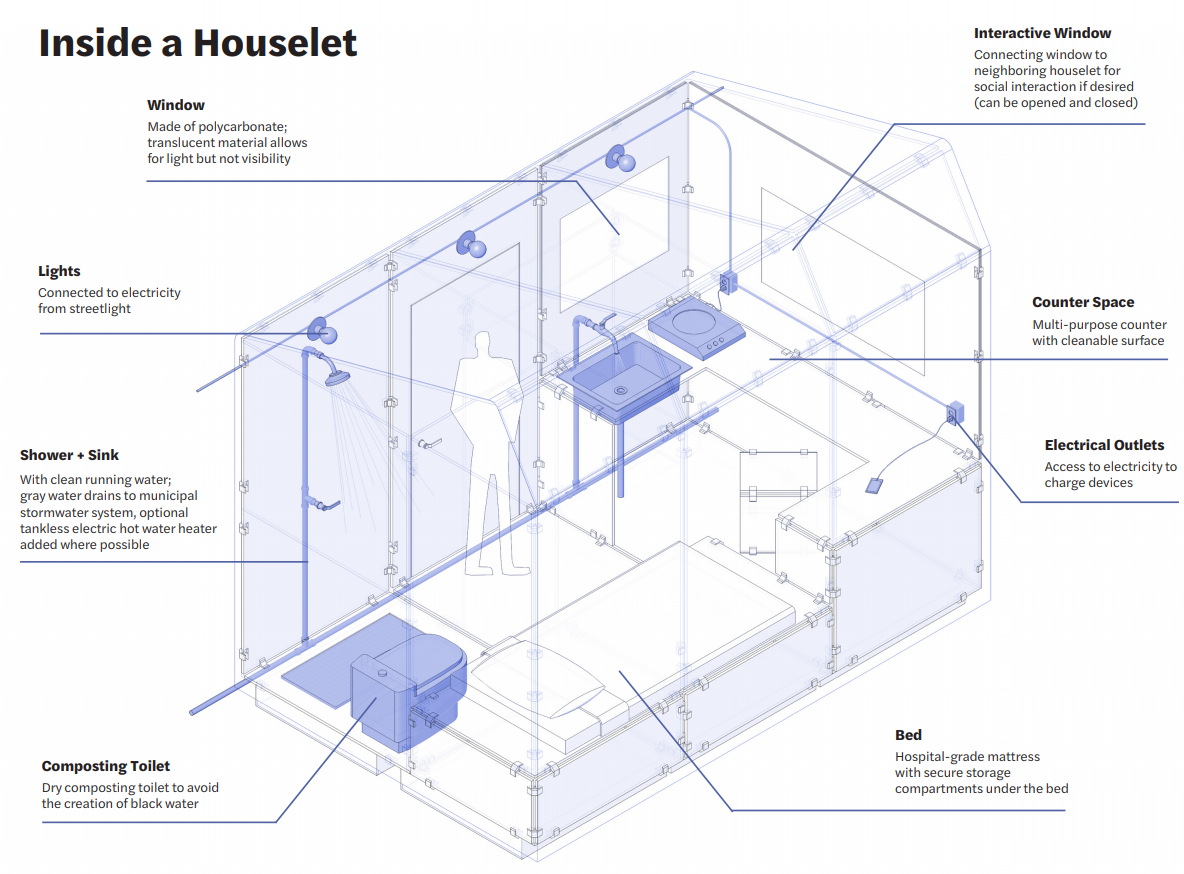

The COVID-19 global pandemic has exacerbated the homelessness crisis and amplified existing challenges that people experiencing homelessness face, including vital access to shelter, sanitation, and digital services. Houselets utilize existing urban infrastructure to create safe, temporary housing for people experiencing homelessness amidst a global pandemic.

Traditional homeless shelters have proven incompatible with this emergency while the demand for a solution has only increased. The situation in New York feels particularly urgent as the typically 24-hour subway is now closing overnight for cleaning. That change came just a day after local authorities referred to the increase in people sleeping on trains as “disgusting.” It was a disappointing thing to hear. While we, of course, understand wanting to protect frontline workers and public transit employees, it is misplaced disgust without solutions. It’s clear that no one wants to be in an overcrowded shelter right now, but alternatives are limited.

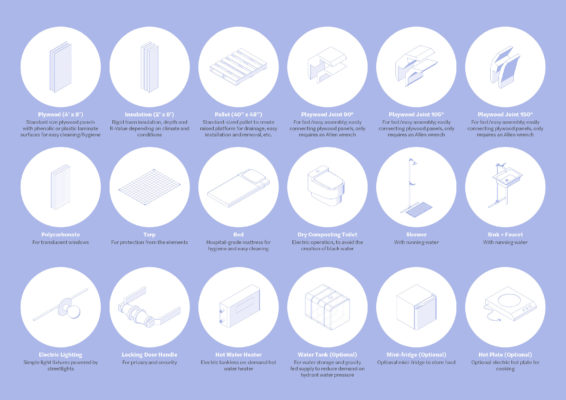

This served as inspiration for Houselet. Drawing on the parklet model, which has become a popular strategy for expanding public space, Houselets occupy existing parking lanes and are designed for quick and easy installation, transition, and eventual removal. As far as where Houselets would be built, we know that the pandemic has prompted an exodus from urban centers. This has reduced the number of cars and created an opportunity to repurpose parking spaces for the deployment of essential shelters. To mitigate cost, construction time, and disruption to existing city systems, Houselets tap into widely available existing urban infrastructure.

Connecting Houslets to fire hydrants provides clean running water for shower and sink facilities in each unit and improves access to sanitation, which is critical during a health emergency like this. Electricity in Houselets is provided by tapping into the existing streetlights that are readily available across most major cities. And finally, in an effort to bridge the digital divide and ensure connectivity, Houselets would be positioned in a way to provide access to existing public WiFi infrastructure, such as WiFi kiosks.

After the emergency passes, Houselets may be removed and parking spaces restored. But, wherever possible, they should be converted into parklets that the general public would benefit from. The materials used to construct the Houselets could easily be repurposed to expand public space across our cities.

People over Property: Affordable Housing as the Cornerstone of Systemic Change

Supportive Housing by Edelman Sultan Knox Wood / Architects – Landing Road / Reaching New Heights Residence

COVID-19 reveals the consequences of New York City’s dehumanizing spatial and environmental policies. As residents, we are all participants in upholding a system of segregation, rooted in unaffordable housing and are collectively responsible for pushing people to live in landscapes of risk while providing few opportunities for health growth or upward mobility. Recovery from COVID-19 is an opportunity to resolve the chronic conditions that underlie this crisis by providing momentum for empathetic action.

The City’s prior recovery efforts, from 9/11, the 2008 mortgage crisis, to Hurricane Sandy, suffered from a myopia that did not address underlying inequities in order to rebuild a better City. After 9/11, substantial tax subsidies through the 421-A program more than doubled the size of the residential community, creating housing for NYC’s wealthiest residents, while the City struggled to find locations elsewhere in the City for new affordable housing. In the aftermath of the 2008 mortgage crisis, NYC worked to stabilize construction markets while bolstering the continuation of speculative purchasing at the expense of owner-occupancy. After Hurricane Sandy, the city focused on reconstruction of prior built conditions, rather than increasing creating new housing opportunities in areas with the lowest amount of environmental risk.

Housing is a human right. Access to stable housing is the foundation of robust public health, a committed and creative workforce, and engaged citizenry. Affordable housing provides every inhabitant with functional independence—alleviating the mental and financial stress associated with securing sleep each night opens up the capacity to take on better and higher challenges. A unit of housing is the currency of stability. As COVID-19 forced residential confinement, even the smallest of spatial irritations (working in a closet, children with no space to play, etc) are manifestations of New York’s residential crisis, and an opportunity to channel frustrations beyond individual circumstance and connect with the magnitude of housing needs facing so many New Yorkers and find compassion facing similar or likely greater, housing challenge.

New York’s explosive growth has roots in the unstable transformation of housing from a social good to an asset class. Market prices bear little relationship to area wages. There is a dire need for a market correction that securitizes well-being. Equitable wealth cannot be not built through property sales or short-term rentals. Building ownership and management must re-center around well-being and stability: land trusts, cooperatives, and new taxes on flipping and pieds-à-terre could bring balance to the residential market. Public investment in over-leveraged buildings could create new affordable units.

Every residential building should be seen as a part of a network of care. Through a shared physical foundation, multi-family housing buttresses tenants through the support system of neighbors. Common spaces bring community discourse. Spaces that allow for play, shared supervision of children, and collaboration are needed now more than ever. The collapse of small businesses and local retail, directly from COVID-19 closures, is a tragedy. These spaces cannot remain vacant. In mixed-use buildings, vacant retail spaces could be transformed into resources of public and community support institutions, such as daycare, new libraries, and incubator spaces. Prior community retail corridors must reconnect with local needs: whether it be for food, services, places for exchange or for gathering, both convenience and connection are perennially relevant.

Like a public sewer system or the electrical grid, affordable housing is essential. New York City is known as the cultural capital of reinvention. This spirit of ingenuity must infiltrate the physical and political infrastructure of the public realm, as increasing access to affordable housing is the only way to end racial disparities in public health and in the economy. Empathetic use of property will bring prosperity to people.

The Housing Livability Index: Questioning the NYC Housing Market

The Housing Livability Index

I moved to Brooklyn, New York in August 2016. In 4 years, I have moved to 3 apartments. This trend of short-term rentals is common for people who have recently moved to New York City. Every time I moved, I learned to look for new factors. Some were obvious such as proximity to public transport, others specific such as the size of the kitchen counter. The unaffordable housing stock makes you choose your evil. When it comes to housing in NYC, there is no way you will satisfy all your needs.

Moreover, we build up a rationale for our compromised living space. At least that is what I did. I thought to myself, I am a ‘City Person’ that spends most of her time in the City. Why do I need a decent apartment with amenities? The apartment is the place where I spent the least amount of time. Despite spending almost 40% of my annual salary, I lived in the tiniest room – with one intermittently working, coin-operated – washer dryer in the basement as an amenity!

Then came COVID-19, and I had to spend all my time confined to the apartment. That is when I realized: Housing in New York City is not only unaffordable, but also not livable. I started observing things that I had not considered checking during my apartment hunt, for instance, the thickness of the walls. The walls were so thin, that they did not obstruct the noise from within or vice versa. It is impossible to have meetings at the same time as my roommate.

The tiny/no kitchen counter space is the rationale for New York’s ‘Take-Out’ culture. Frantic cooking to kill time during the pandemic made me realize this shortcoming. I decided to create a list of housing factors that were important to me pre and post-pandemic. In dense cities like NYC, the location of the apartment was more important than the livability of the apartment. This pandemic has allowed us to take a hard look into the housing conditions and policies of the city.

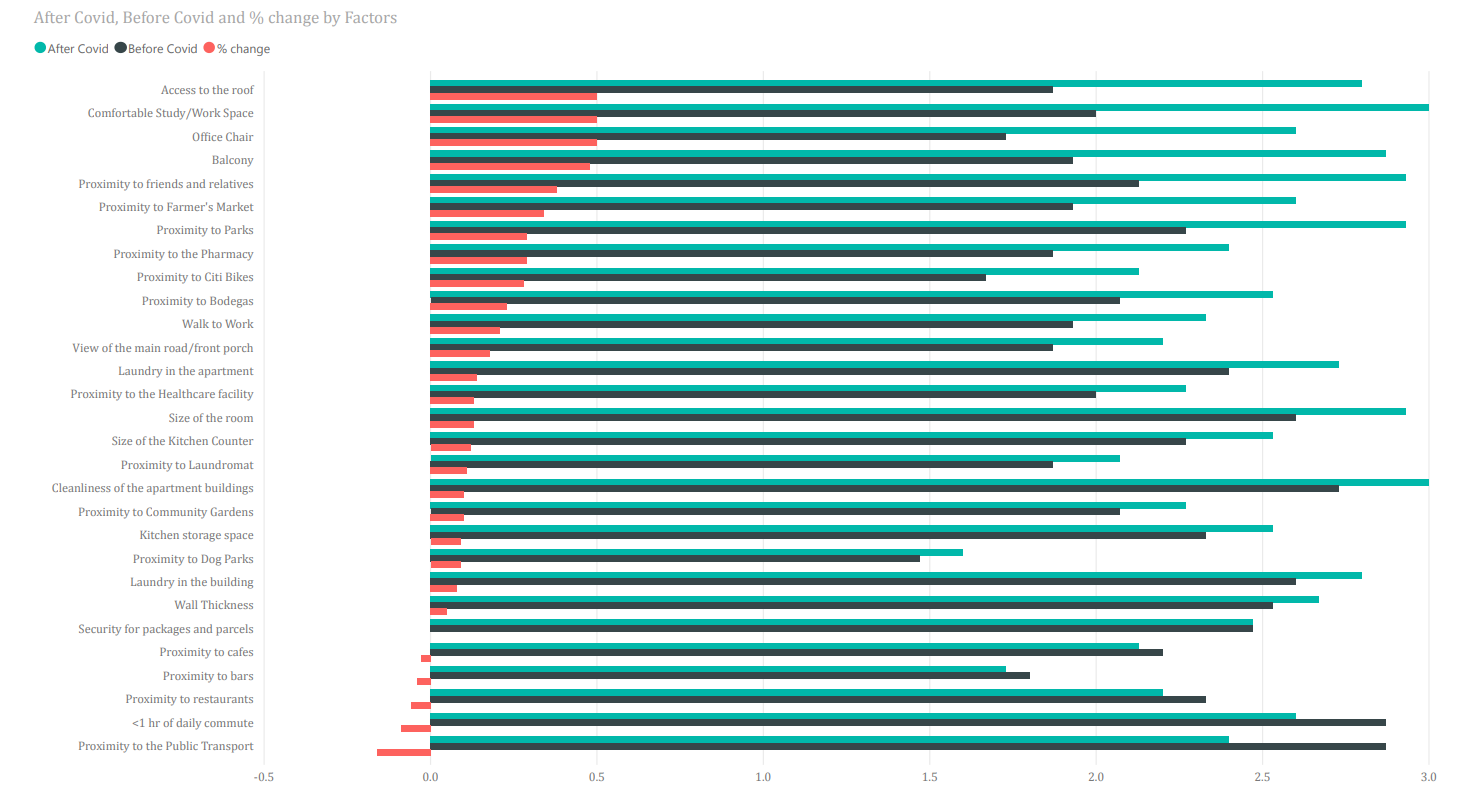

The goal of this project is to collect data via a survey to understand the Change in Apartment Hunt factors (in Cities) due to COVID-19.

Attached is the data that was gathered from the survey spanning 29 factors gathered from 16 different candidates. The 3 most significant factors that were prioritized more after COVID-19 were:

- Comfortable Study/Workspace

- Office Chair

- Access to the roof

On the contrary, the participant’s priority declined towards these factors:

- Proximity to restaurants

- <1 hr. of daily commute

- Proximity to Public Transportation

- Proximity to bars

- Proximity to cafes

Out of the 29 factors considered, only 5 factors had a negative impact, stated above and 23 factors had a positive impact after COVID-19, indicating that the participants did take a much closer look towards many aspects of the apartment search, which were overlooked before.

An Analysis of COVID Impact Based on Location

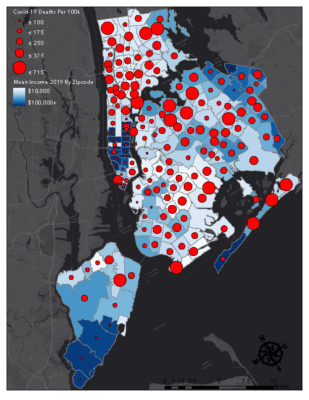

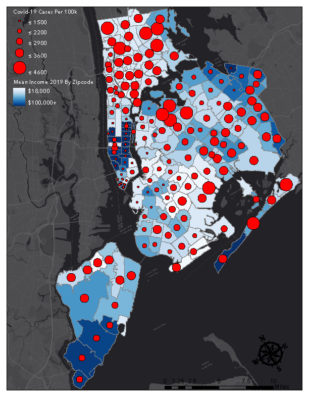

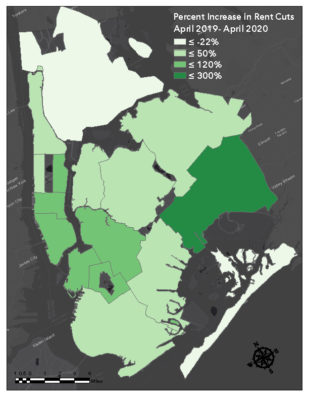

The following maps display some of the effects of COVID-19 on the city and how these effects have varied spatially and economically across the city. The first two maps display COVID-19 case rate and death rate by zip code over income in order to show how income affects the spread and deadliness of the virus. The final map displays the percent change in rent cuts by submarket when compared to the same month in 2019 in order to show how the virus has affected rental prices across the city.

Income and demographic data for NYC was acquired from the American Community Survey (ACS) and Covid-19 case rate/death rate data was acquired from the NYC Coronavirus Disease 2019 Data repository. Since the data from the ACS was organized into census tracts, this was converted into zip codes for easy use with the city’s COVID-19 data.

Overall, it is quite clear from these maps that residents of the poorest areas of NYC are also the most likely to contract AND die of COVID-19. This is very clearly displayed in the disparity between Central Manhattan and the Bronx. We see that cases and deaths are low in Manhattan while the Bronx, on average one of the poorest areas of the city, has both the highest case and death rate from COVID-19 accross the city. Rent cut data was downloaded from the StreetEasy data portal, and this metric simply represents the number of listings that experienced a price cut in a given month. Data from April of 2019 was compared to April of 2020 in order to find a percent difference.

This map shows that most of the city (outside of the Bronx and the Rockaways) have experienced a significant share of rent cuts compared to last year. This tells us that COVID-19 is forcing many landlords to cut rents in order to combat the lack of demand for apartments in the city due to the virus.