After months of isolation, the importance of developing safe social infrastructure is key to rebuilding healthy cities. The pandemic has drastically shifted the way we socialize and create networks between each other. We feature proposals that investigate emergency response methods on a local scale, providing elderly populations support in recovery, and the fast-acting power of mutual-aid groups. Scroll to read all 5 proposals.

Understanding Our Future Social Infrastructure

Design For Six Feet: A Crowd-Sourced Catalog of Ideas for Restarting Urban Life

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Urban Design Forum launched City Life After Coronavirus, a digital program convening Fellows and international experts to document global responses to the current crisis and to strategize a road to recovery for New York City. In April, we released a Call for Ideas to our network soliciting a broad range of submissions that envision how urban planning and design should change in the wake of Covid-19 as we strive to build a more just city for all New Yorkers. We are featuring some of the most compelling ideas in a series of reflections and proposals about diverse topics like education, community engagement, and mobility. Explore the full Gallery of Urban Ideas here.

Understanding Our Future Social Infrastructure

Humans by our nature are social beings. During this time of the pandemic, we are continuously adapting our interactions with one other. Many of us have been utilizing technology to connect digitally or the trend of singing or cheering at 7 pm from our balconies and windows; both early accommodations responding to social distancing mandates.

Socializing is vital to how we live. Not only in how we understand and connect with others in our personal relationships, but the various collaborations required of our core work as passionate designers. The pragmatics of socializing needs to be reconsidered to inform our work in addressing the future public realm. This work requires collaboration, simply because the public realm is far too complex for any one person or discipline to engage alone.

In Kevin Lynch’s book Image of the City he proposes that created in the minds of people experiencing a city, is a mental map composed of Paths, Edges, Districts, Nodes, and Landmarks. Today, we might expand this notion of internalized topographies further, with the understanding that Lynch’s urban elements are idiosyncratic and deeply personal. For example, a district could be perceived simultaneously as both vibrant and desolate – it depends on who is imaging the city. Considering this, we might ask how the social infrastructure of our cities can contribute and expand these maps and become a clearer, shared physical network that stitches together many places and people.

We understand and occupy our cities via the social infrastructure that is in place. Today, examples include our transportation corridors, parks and plazas, libraries, museums, cafes and restaurants, schools, healthcare and community centers, and other facilities that support daily life. In this time of the pandemic, along with the pursuit for greater social and environmental justice, how might our social infrastructure adapt to create a more robust and expanded network for all?

In the most basic sense, the role of architecture throughout history has been to provide shelter. As we look more to outdoor environments in response to the restrictions the ongoing pandemic imposes upon us, we begin to see how, in partnership with architecture, landscape architecture takes on an even more pronounced contribution to an expanded notion of shelter. Together we can begin to envision and adapt our cities and urban spaces to expand our social network; from restaurants in our streets to classrooms in our parks. Our definition of shelter might now take on the added necessity of being read from multiple points of view.

As we consider our collective future, we should explore a variety of questions:

- What is the role social infrastructure has played within our communities and how might this evolve or expand? How can this current situation help re-envision our core values of social infrastructure?

- How might the methods in which we socialize adapt? Where will we meet, when and how? What are the modes of connection we will utilize? How will our perceptions of safety influence the nature of how we socialize?

- In what ways can past pandemic responses inform adaptations we make today? Can our outdoor landscape become more deftly intertwined with schools, restaurants, or other historically indoor activities?

- Can we find ways to promote the chance interactions that bring us together with those who have differing points of view or life experiences; each helping us to understand and relate with broader, more diverse, points of view?

Snøhetta began with, and continues to embody, a belief that we can accomplish more if we do it together. No singular discipline or viewpoint is enough to meet the complexities and demands that the built environment requires for societies to thrive. For over thirty years, their transdisciplinary approach has manifested in work that ranges from the reconstruction of Times Square to the Oslo Opera House; from the Willamette Falls Riverwalk to Calgary Central Library; and from dollhouses and beehives to numerous high-ambition, sustainable designs. The practice places personal and social experience at the center of their design process. Their work engages the senses and physicality of the body, fosters social interaction, and promotes both individual and collective empowerment in the built environment. Snøhetta is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Aga Khan Award, Mies van der Rohe Award, the AIANY Medal of Honor, and the European Prize for Public Space. With seven studios globally, the practice integrates architecture, landscape architecture, interior design, graphics, branding, and product design into memorable and inclusive environments around the world.

Improving NYC for Aging Populations

Once seen as an equal opportunity virus, we have now witnessed how COVID-19 has torn through vulnerable communities and surfaced the inequities of our world. Among the most vulnerable of these communities are seniors, who make up roughly 73% of COVID-19 deaths in New York City. As we see how places like retirement homes, public spaces, and grocery stores become less safe and less accessible for seniors, it becomes clear that a vulnerable group like the aging population and the challenges that they face in the urban environment should be put front and center rather than in the periphery when designing for urban life.

In light of COVID-19 and beyond, we propose the following ideas to help seniors age in place:

- Expanding the role of postal workers;

- Introducing seniors-only hours in New York;

- Prompting intergenerational relationships digitally; and

- Creating joint housing arrangements for seniors and affordable housing residents.

We view these solutions as holistic approaches to improving cities for the aging population as it can address concerns about mental well-being, access, agency, and physical safety — which can potentially be beneficial to other populations as well.

Expanding the role of postal workers

Inspired by Japan Post, we see the potential of the post officer’s role to not only deliver mail from house to house, but also to provide support to those they deliver mail to. This can be especially comforting for seniors who have little to no physical and social interaction with others. Not only is this an opportunity for seniors to stay connected with their loved ones, as it is also a worthwhile opportunity to rethink the US Postal Service’s role in our communities and save it from the dire financial challenges it currently faces.

- Post officers can visit homes of seniors and check-in on them by asking how they are doing and providing any necessary social support. Family members and friends of seniors can subscribe to this service at an affordable rate (priced on a sliding scale), which will in turn contribute to increased revenue for the money-strapped US Postal Service

- Postal workers can exchange notes or log responses for family members to look at, which can help family members track the well-being of their loved one

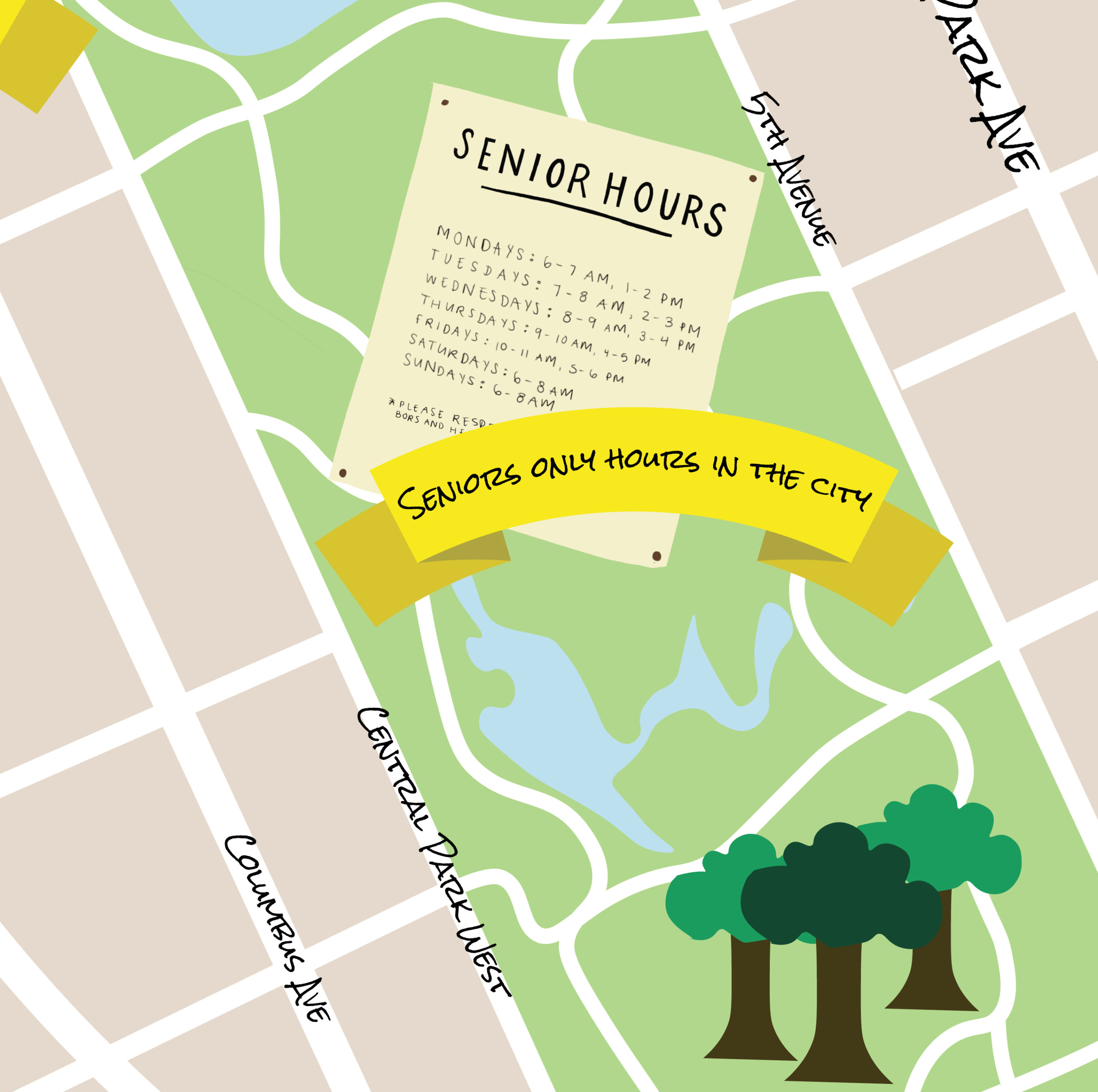

Introducing seniors-only hours in New York

Inspired by the seniors only grocery store hour guidelines, we propose expanding the seniors-only hour concept to other aspects of public life. This entails that during certain hours of the day, most individuals stay indoors, while seniors can take time to go outdoors. By implementing this rule, seniors can have time outside to exercise or take a stroll while feeling safe about doing so.

Aside from designated hours, providing designated areas for seniors within public spaces can be another configuration of this initiative. Spaces such as parks, plazas, and public libraries can have senior-exclusive areas that will be designed particularly for their comfort and pleasure. This could look like having a seniors garden within a park or a seniors patio at the library, where there can be ergonomic chairs for the elderly and programs like exercise and bonding activities.

Prompting intergenerational relationships digitally

We propose using intergenerational programming to create connections between children and seniors that will combat loneliness and psychological fallout brought about by prolonged isolation.

Ideas for such programs include:

- Incorporating a Pen Pal program to connect seniors and children, which can be done through a partnership between schools, youth centers, senior centers, retirement homes, andnursing homes.

- Providing technology training to seniors to connect them to digital platforms such as online exercises, meditation classes, discussion groups, and workshops. The New York Public Library has thousands of similar free, public programs such as the TechConnect program, and a separate initiative focused on providing seniors with access to necessary hardware and software will be a valuable first step for them to participate in these online programs.

Such efforts can also potentially inspire the design of devices and digital interfaces for seniors.

Creating joint housing arrangements for seniors and affordable housing resident

NYC has long had a housing affordability problem and the city can also be very isolating, especially in light of social distancing. We propose an affordable housing model that combats social isolation; housing units that pair seniors who live alone with individuals in need of affordable housing, for example, students or artists.

As a way to subsidize their rent, individuals might contribute by helping the senior to do chores which are too physically demanding, walking their dog, checking in on them when they are sick, and spending time with them. This model will provide the social and community support that is so important for seniors, but the model is really about reciprocity. Seniors have much to offer the relationship as well; they have lived experiences to share and they often have more time for things like cooking or caring for houseplants. Additionally, seniors aren’t the only ones who experience social isolation, especially during COVID-19; many individuals experience loneliness when they live far away from family or just by themselves, and stress when dealing with things like a job loss or a health concern.

Through this housing model, both parties will gain greater, more intergenerational social connections and in the case of a future pandemic, can be a part of an isolation pod together, ensuring the continued physical and mental well-being of each other.

There are many possible arrangements for this:

- Affordable Student Units in a Market Rate Seniors Building

- Modeled partially after Humanitas Retirement home in the Netherlands

Unoccupied rooms in seniors-owned houses will become potential living spaces for students who are deemed to have financial need, which could be determined based on an application and selection process facilitated by partner universities. Each chosen student will be trained on how to support seniors, then paired up with a senior buddy to spend a certain amount of time hanging out or helping them out each week. In return, students get subsidized rent and their own living space.

- Modeled partially after Humanitas Retirement home in the Netherlands

- Artists-in-Retirement-Residence

- Modeled after Judson Manor in Cleveland, Ohio

Similar to artists-in-residence programs, artists and seniors live together in a housing complex. Artists are given living and work spaces and give lessons and/or performances as well as socially contribute to the retirement home.

- Modeled after Judson Manor in Cleveland, Ohio

- Home Share

- Modeled after the Toronto Home Share Pilot Project

Seniors who own their property and have an extra room lease it out to qualified individuals with financial need. Individuals contribute socially as well as by taking on household chores and errands

- Modeled after the Toronto Home Share Pilot Project

Reflections

The above mentioned proposals aim to help seniors age in place by redesigning city services to mitigate health risks and allow for increased agency. Seniors should be at the center of planning and implementation rather than at the periphery. We believe that the future of the city post pandemic needs to prioritize the needs of vulnerable populations – which means seniors and other populations should be involved as power holders and decision makers in urban design. Solutions designed for seniors in turn make the city better for everyone. Addressing the needs of seniors will greatly help to create a more just New York City.

Amplifying Emergency Response on a Local Scale

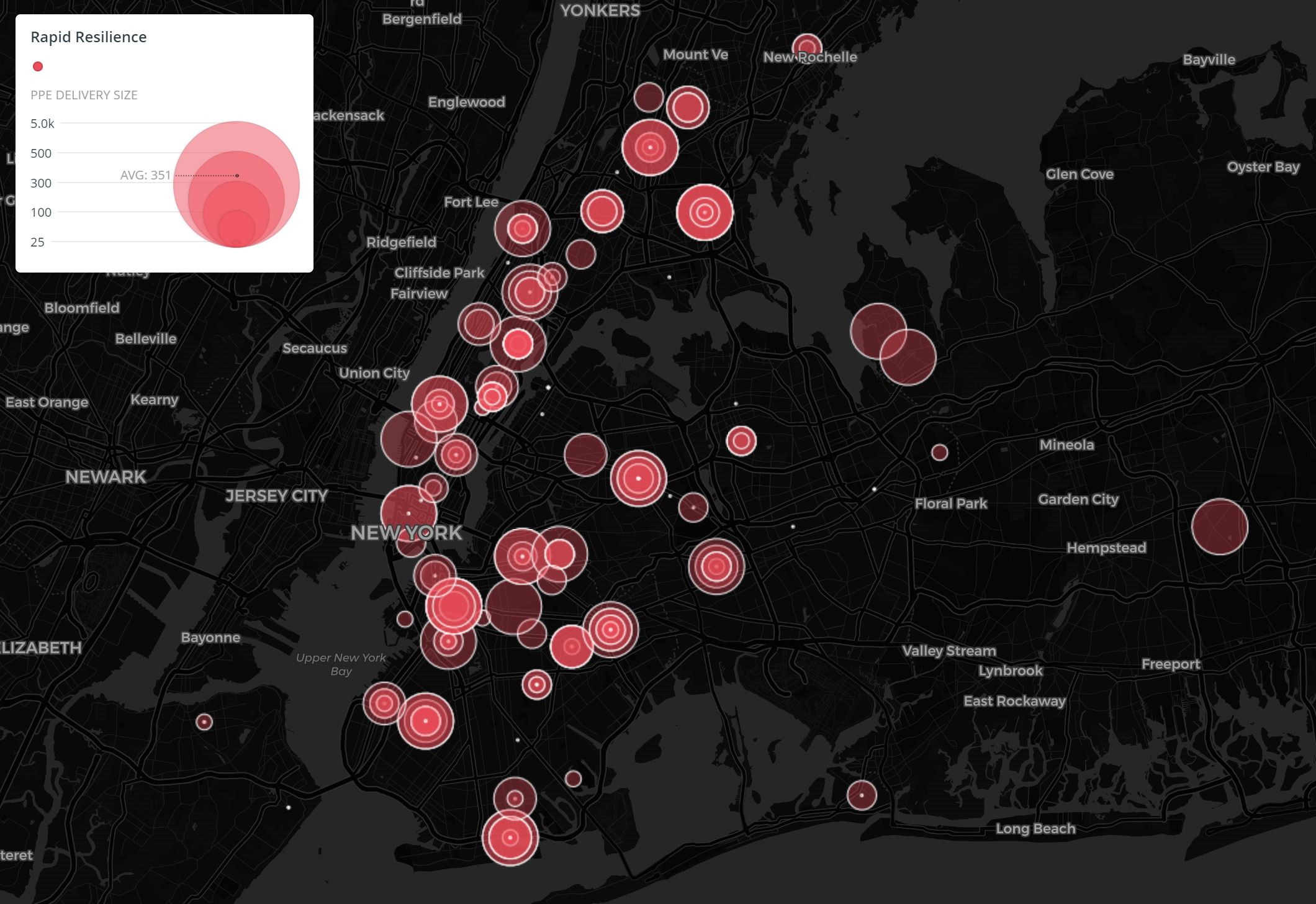

Rapid Resilience is a deployable emergency response program that was formed during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic as a platform for grassroots emergency response initiatives. Rapid Resilience empowers grassroots aid efforts in disenfranchised communities and since its initiation in March, has delivered personal protective equipment (PPE) to medical workers across the country.

Additionally, the program provided COVID-protection in vulnerable low-income communities including, prisons and Native American communities, and built urban cooling infrastructure for heat waves. Rapid Resilience’s model has and continues to support and amplify local end-to-end emergency response and recovery efforts.

Background: From a Local Campaign to a National Network

A crisis can shift priorities in profound ways. During the height of the first COVID-19 outbreak in March, it became clear that modes of operation had to change and high-speed, collaborative action was necessary to stop the exponentially growing public health crisis. This is what sparked the MaskForce, a group of volunteers working with the Brooklyn-based nonprofit RETI Center to deliver triage PPE to frontline healthcare workers.

Delivery of protective masks to prison medical staff during the height of New York State’s outbreak.

Recognizing that many fast-paced volunteer efforts burn-out, the group formed Rapid Resilience, a RETI Center initiative. Conceived as a centralizing platform and support-structure for volunteer-led efforts, Rapid Resilience maximizes the impact of independent, crisis response-related campaigns like MaskForce. What started as a single team’s COVID-19 PPE response has become an emergent network of disaster response initiatives that responds to crises as they arise on the ground.

A Model for a Scalable & Adaptable Disaster Response

Rapid Resilience is an organizational model for collaboration and action for a wide range of issues. As a scalable network of individuals and groups plugged into vulnerable communities, Rapid Resilience is able to adapt to crises as they arise, and shift efforts based on feedback on the ground. This action-oriented grassroots model works beyond the demands of COVID-19 as a way to respond to any emergency, including climate change.

A core mission of Rapid Resilience is to provide aid for communities faced with disaster through grassroots tactics. Before COVID-19, RETI Center’s programs focused on justice in the face of climate change, by building strength in communities through resiliency-focused economic development. It was observed that the same disparities that make communities vulnerable to climate change are highly correlated to COVID-19 casualties. In disasters in general, whether it’s a pandemic or extreme weather event, disproportionate damage falls on low-income populations, particularly people of color.

Protective equipment was delivered directly to medical workers based on level of need. Rapid Resilience supplied PPE to these frontline healthcare workers in Boston when they were facing shortages.

The Rapid Resilience network extends to individuals and groups providing aid in hard-hit communities across the country, working with them to give them the tools they need to fund the purchase of PPE and other aid supplies, and maximize their impact through streamlined processes. By working with the Rapid Resilience network, local initiatives across the country gained access to resources and support for each of the steps of the emergency response process.

First Responder for First Responders

Rapid Resilience began as a response effort to protect the frontline medical workers. A lack of coordination and proactive action from state and federal governments has led to waves of critical PPE shortages. The core problem the team identified was a disconnect between large-scale suppliers (mostly in China), centralized hospital administration, and the frontline medical staff who need comparatively small quantities of PPE. This supply-chain shortage was most acute at healthcare facilities in low-income communities.

Through their coordinated efforts, Rapid Resilience plugged this gap by fast-tracking supplies from factories abroad, and kept costs low by aggregating individual campaigns into a unified PPE-purchasing collective. PPE requests are received directly from medical workers, and assessed by level of urgency. Once supplies reach Rapid Resilience teams, volunteers deliver them directly to healthcare professionals. The group learned several key lessons it continues to apply; combined sourcing reduces cost and corruption in the supply-chain, and direct communications with people in need ensures the right amount and type of supplies are delivered.

To-Date the Rapid Resilience frontline worker campaigns (MaskForce, Last Mile, Mission:Masks, and Masks for Midwives) have delivered 100,115 pieces of PPE equipment to frontline medical workers across the country.

PPE to the People

As supply chains adapted to meet the demand for PPE in the medical community, Rapid Resilience organically shifted its efforts to providing protection to essential workers and high-risk populations that were being disproportionately exposed to COVID-19. Working with local contacts the Rapid Resilience network was able to provide non-medical PPE to the Black Lives Matter organization, public housing residents, nursing homes, Native American reservations in the Southwest and Midwest, and essential workers lacking adequate resources.

To-Date Rapid Resilience campaigns (Last Mile, PPE New Mexico, and Rapid Resilience central) have delivered 7,380 pieces of PPE to vulnerable communities and groups across the country.

Cool Streets NYC

The Rapid Resilience group has recently launched the Cool Streets program, in partnership with the Center for Resilient Cities and Landscapes, to design shade and cooling structures with the community to protect people from extreme heat in NYC when city facilities are inaccessible.

From the beginning, the Rapid Resilience team has been cognizant of how racially and economically-based impacts would escalate, and the public amenities we all enjoy access to are the commons that we all share and the places where we meet and interact. However, for low-income communities, there are no alternatives to mass transit, parks as outdoor spaces, and the streets as community spaces as our public facilities closed for an indeterminate time. We have to keep in mind future asymmetrical dangers that will escalate as a result of further reductions in “the commons,” those public amenities we benefit from.

Check out the Interactive map of deliverables made through the Rapid Resilience Initiative.

Rapid Resilience is an initiative of NYC-based Resilience, Education, Training and Innovation (RETI) Center — a 501(c)3 nonprofit born out of Superstorm Sandy with a mission to build resilient communities. Guided by the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and OneNYC 2050 – New York’s Green New Deal, RETI’s work strengthens waterfront communities through Resilience, Education, Training, and Innovation.

Bau Land: The landscape and planning firm Bau Land played a key role leading MaskForce and in the formation of Rapid Resilience. Bau Land works to improve communities resilience through systemic planning and the integration of landscape in design, from products and buildings, to public parks and master plans.

Mutual Aid as a Long-Term Solution

At this time of nationwide lockdown, people are physically apart; we also realize once again, in the nonphysical sense, how discrete the country is, and so is the world. People experience different realities: some are hearing ongoing sirens, mourning without saying proper goodbye to family members and lining up for food for hours while others can safely stay at and work from home with all resources at their disposal. People have disparate solutions, and some with none for this crisis.

Longstanding equity issues surface as funding, healthcare and other resources get stretched and strained. These problems will only exacerbate, creating more polarized cities, if we do not take concrete measures to address them. One step towards a resilient and just recovery is to bridge the gaps by strengthening social connections and facilitate intergroup conversations, so people start hearing different voices and understanding each other. Many mutual aid projects have made the news since the beginning of the pandemic, and new relationships are formed everyday.

Well-resourced college students are talking to empty nest seniors. Block residents are helping their neighbors working on the frontline to take care of their children while they perform their duties. These interactions are precious, because people get to connect with others on a personal and intimate level, especially with those who they might not have the opportunity to do so in a normal world.

Invisible Hands is an amazing initiative that came to fruition once a group of twenty-somethings realized their community needed help. This video shows the beauty of mutual aid work.

Many more social connections were already well-established prior to the crisis, and this trying situation only affirms the importance of reinforcing them. My nonprofit organization supports grassroots community improvement projects in New York City, and we’ve witnessed neighbors, gardeners, parents, teachers, artists, tenant organizers and activists bringing their communities together to make their neighborhoods better. Our work and that of those in our network are the complete opposite of “social distancing.”

We shall probably phrase it as “physical distancing,” as in this new reality, the community organizing work is not ceasing but only taking other forms, such as virtual communications or just standing six-feet apart. The grassroots leaders are still working hard to support their community members, and in some instances they appear to be positioned well for these tasks. COVID-19 is a pandemic and concerns all, but it is also highly personal: people are losing loved ones, trying to pay for rent and essential items and dealing with a lot of stress. Therefore, providing the necessary assistance and support requires sensitivity and compassion. Grassroots leaders usually know their group members or are known by them, so they see well or can figure out the specific needs and resources in their respective communities.

As these dedicated leaders occupy a niche in the relief and recovery schemes, government officials, experts, scholars and others with resources shall hear from them and back them up. This particular moment avails opportunities to reexamine community groups’ ongoing outreach strategies, enhance existing connections and identify new networks as well as partnerships.

Besides financial and other basic resources, cities shall cultivate an environment receptive to positive social connections. In addition to technical support on outreach strategies, providing internet connection, devices and relevant infrastructure can also be instrumental in many neighborhoods as people are connecting in new ways.

Whether to sustain the new relationships formed during the pandemic and how to achieve that goal is yet to be determined, bu we could potentially transform the mutual aid efforts to long-term rescue for disadvantaged population or emergency preparation. Reinforcing established networks will allow for more equitable development as a collective voice is often stronger and harder to suppress than an individual outcry.

When we surveyed and talked to community leaders in our network, we found out that access to mental health support was among the top priorities. Before rebuilding the normalcy, we have to recognize and heal the wounds first; facilitating empathetic inner- and inter-group conversations may be one of the remedies. For example, youth might experience depression as they are separated from friends, witnessing passing of close family members and receiving little instructions with remote learning. Many need to process these emotions with a close circle of people that they are comfortable with.

On the other hand, other stories need to be heard by more. Reading about homebound residents in a tweet is never as compelling as hearing about the plights in person. However, we shall also take caution to not exploit the narratives as they contain people’s real sorrow and trauma. The fast-paced and omnipresent information sharing through the web these days creates the illusion that we are more connected and know more about others than ever before.

When we become satisfied with objecting another person with a “punchy” new comment on Facebook and never go back for their response, or get into quarrels without substance, we are shutting down communications. Intergroup connections may be constructive if we can facilitate effective conversations, not necessarily aiming to reach an agreement but to truly hear the other perspectives. Cultivating social connections and promoting empathetic conversations are not the panacea to all the problems that we are and will be facing, but shall lead us to a more equitable recovery post-Coronavirus.

Design For Six Feet: A Crowd-Sourced Catalog of Ideas for Restarting Urban Life

Since the @designforsixfeet Instagram account was launched in mid-May we have received submissions and ideas from around the globe – from individuals, neighbors and community groups, and municipalities who are responding to the pandemic with speed and creativity. Many of these ideas were meant to be experimental and short-term, but we are already seeing that some might be here to stay.

Since launching, we’ve seen a shift in the type of tactical urbanism solutions that have been shared with us on Instagram. In many ways, this shift reflects our changing understanding of how COVID-19 is transmitted, our responses to new municipal policy and government regulation, and a deepening sense of the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic on communities.

As those who were lucky enough to stay sheltered in place ventured out into public space again, we saw a focus on regaining mobility while maintaining distance. Miles and miles of new bicycle lanes were rolled out, tape redefined our movements, and people were playful about how to use ‘nature’ as a divider. Neighbors interacted from balconies and in courtyard spaces (and people shared proposals for how to rethink zoning to make sure it is easier to build these types of spaces moving forward).

We saw “physical distancing” give way to “social distancing” with the rigid circles and dots becoming a bit more fluid. Streets, sidewalks, and parking lots continue to be reclaimed by people for al fresco dining, Zumba classes, play streets, and more. And throughout it all, we have seen people making their design solutions available to all — from building public handwashing stations to upcycling materials to construct barriers for outdoor dining to designing play equipment.