From neighborhood pre-Ks to sprawling university campuses, educational facilities are community hubs that can provide public space and services benefiting people beyond just students. As Mayor DeBlasio pushes for in-person K-12 schooling this month and college students return to NYC from around the globe, we feature two exciting proposals that consider how educational institutions can retool their campuses for Covid testing, economic recovery and recreation.

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Urban Design Forum launched City Life After Coronavirus, a digital program convening Fellows and international experts to document global responses to the current crisis and to strategize a road to recovery for New York City. In April, we released a Call for Ideas to our network soliciting a broad range of submissions that envision how urban planning and design should change in the wake of Covid-19 as we strive to build a more just city for all New Yorkers. We are featuring some of the most compelling ideas in a series of reflections and proposals about diverse topics like education, community engagement, and mobility. Explore the full Gallery of Urban Ideas here.

Reopening K-12 Schools After COVID-19

A Planning Strategy to Guide Implementation

Is there a way to safely reopen more than 1,800 K-12 schools in New York City in a responsible way to educate over 1.1 million students?

Reopening will require a reliable screening and testing system to evaluate teachers and children daily. Ideally there would be a screening and testing facility at every school, call it front porch healthcare. Mitchell Giurgola has been exploring an actionable plan to scale “front porch” healthcare to serve every school in NYC and has developed a strategy and physical plan that will allow NYC agencies to implement a robust K-12 school community-based screening and testing program.

This proposal is intended to provide a nimble analytic tool to site facilities and an adaptable infrastructure for health care providers working in partnership with the Department of Education. Mobility will be critical not only to overcome the challenges of Covid-19, but also to prepare for the upcoming flu season, the next unforeseen global health crisis, and simply to monitor children’s general health with meaningful frequency.

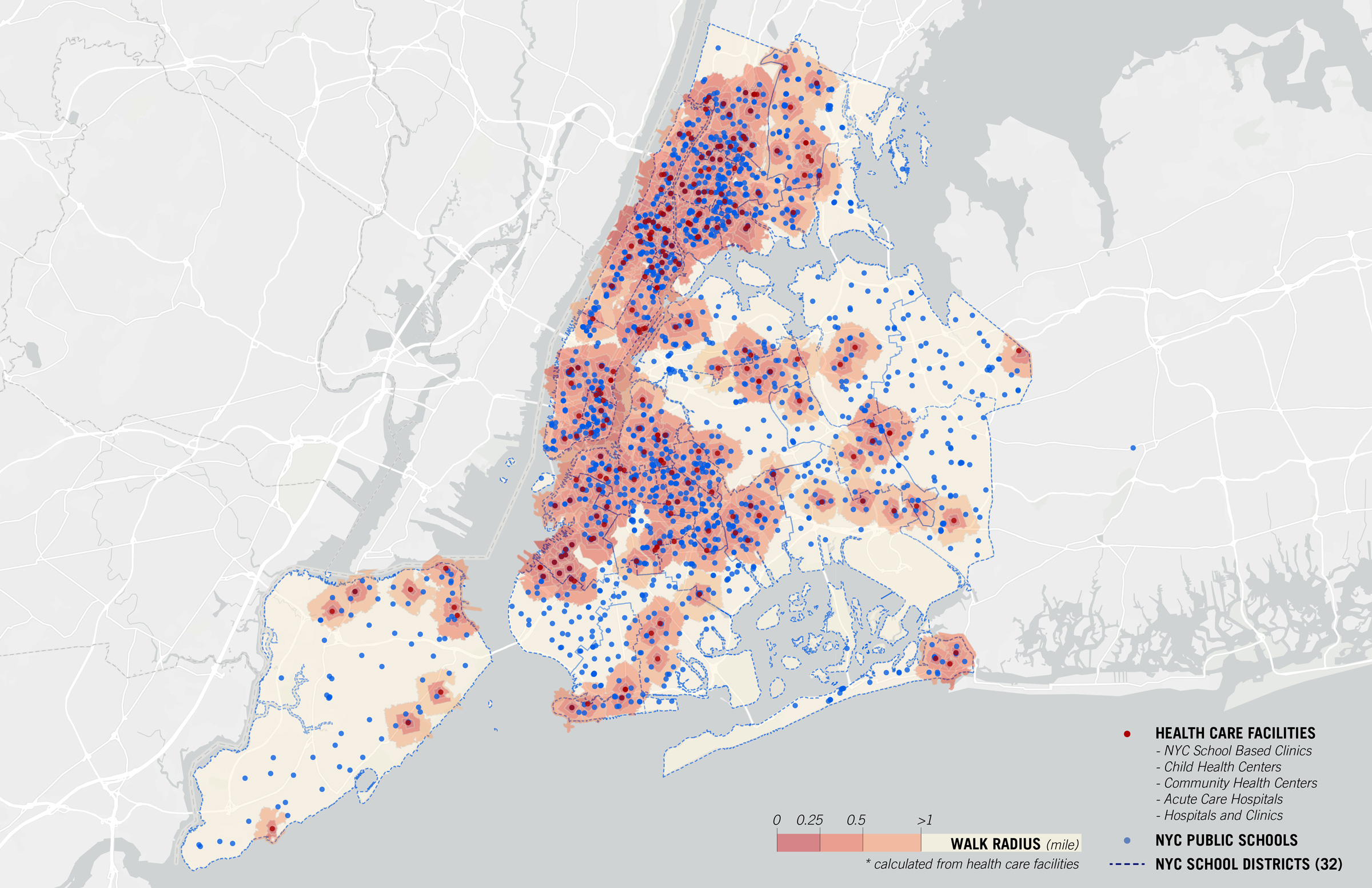

By studying the existing network of the Health + Hospitals Corporation, the Department of Health and other municipal-funded providers, the plan highlights ‘hospital deserts’ where pop-up healthcare installations will be needed.

Using GIS mapping technology and data analysis, every school in the five boroughs has been geo-located in its school district. Hospitals, public health centers, and clinics managed by the Health and Hospitals Corporation, Department of Health and community-based non-profits have been flagged, as have school-based medical clinics. By overlaying existing healthcare facilities onto the Department of Education’s 1,800 schools, the mapping study identifies underserved areas, and helps to pinpoint school clusters and potential sites that merit pop-up satellite health centers.

The analysis acknowledges the involvement of more than a few agencies who must coordinate their efforts: the Governor, the Mayor, the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services, the Department of Health, the Department of Education, the DOE school based clinics, and Health and Hospitals Corporation. For the purposes of the study and proposal, the assumption is that a coordinated effort among the agencies will be in place. Any less, as we have witnessed at the Federal level, will severely limit the chances for success.

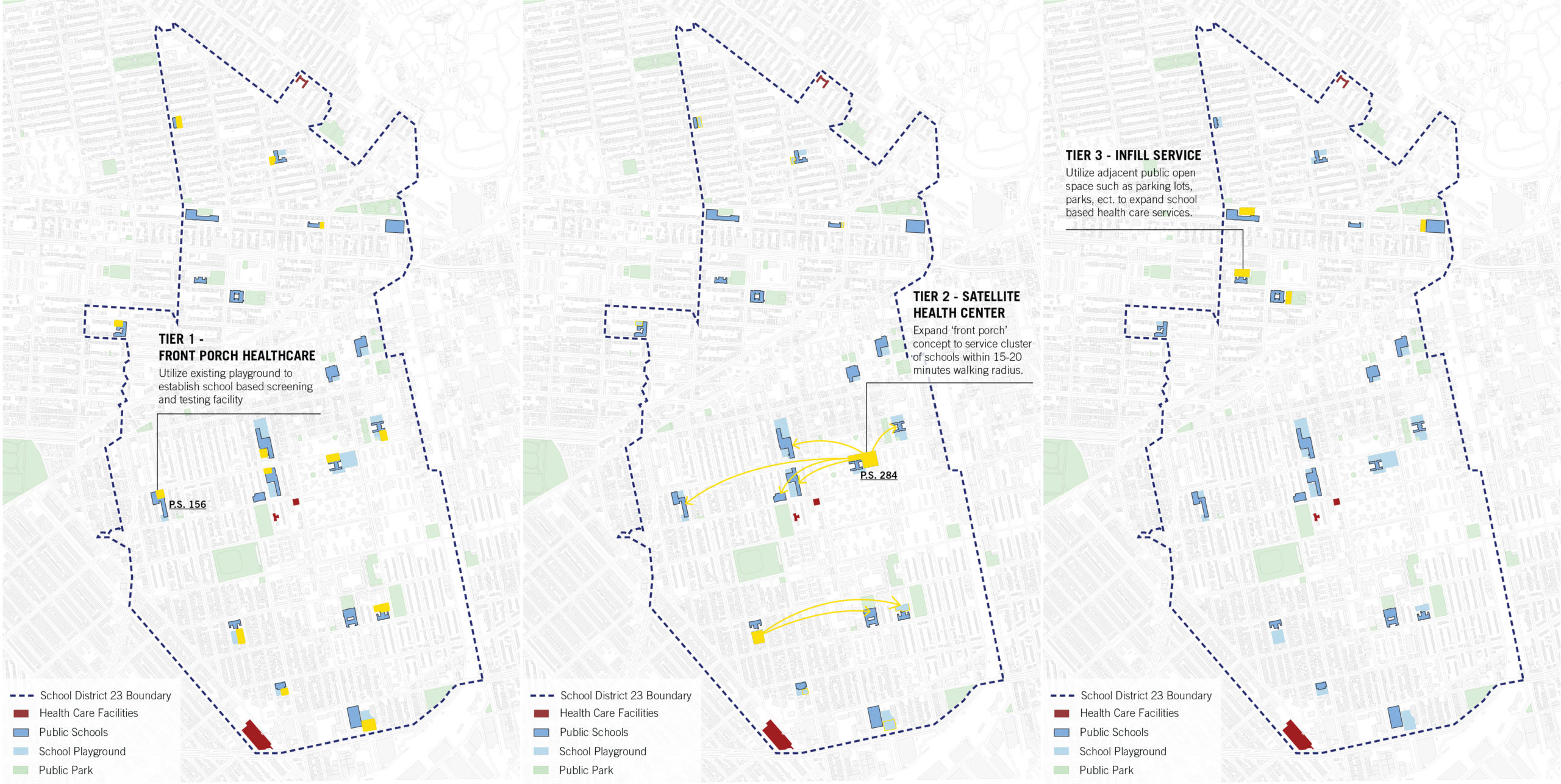

To meet the CDC reopening guidelines, every school in NYC will need a designated spot for screening, testing and healthcare outside of the school building surrounded by fresh air and ease of social distancing. Mitchell Giurgola has identified three possible solutions to respond to this need. The first solution, Tier 1, involves utilizing a school’s existing playground as an outdoor, sheltered zone for screening and testing before students and staff enter the building.

Given the density of NYC’s urban landscape, however, a more realistic and cost-efficient planning concept is to identify neighboring schools that are sufficiently close to share a satellite facility (Tier 2). By scaling the ‘front porch’ concept, this solution allows a single screening center to serve a cluster of schools on larger unencumbered sites. These satellite health centers should be located within a 15-20-minute walking radius from a cluster of schools.

The third solution involves utilizing adjacent public open space (i.e. parking lots, parks, etc.) to expand school-based health care services. A representative school district, District 23 in Central Brooklyn, illustrates the planning process to identify clusters and solutions.

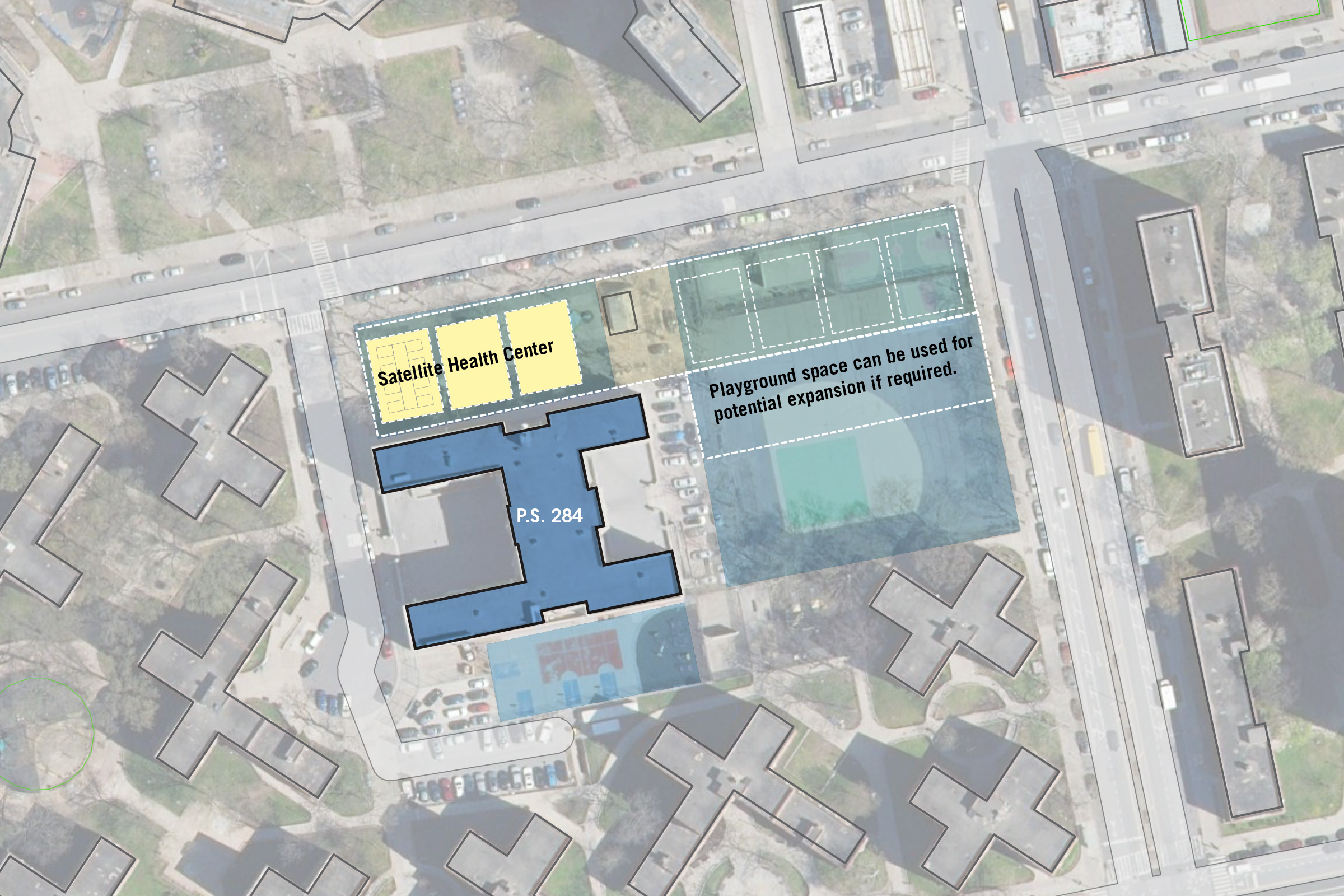

An aerial survey of the fabric of the neighborhoods reveals potential sites for satellites to serve a cluster of schools. For example, in District 23 there is a cluster of five schools in proximity to PS 284. To reduce the number of individual screening pop-ups, the District managers could decide to develop a satellite facility to serve both PS 284 and the other 4 schools within a walking distance of 15-20 minutes, a cluster.

In District 23, several schools are isolated in relatively remote locations, which is commonly the case. In these cases, a singular front porch would be appropriate as illustrated in the example below.

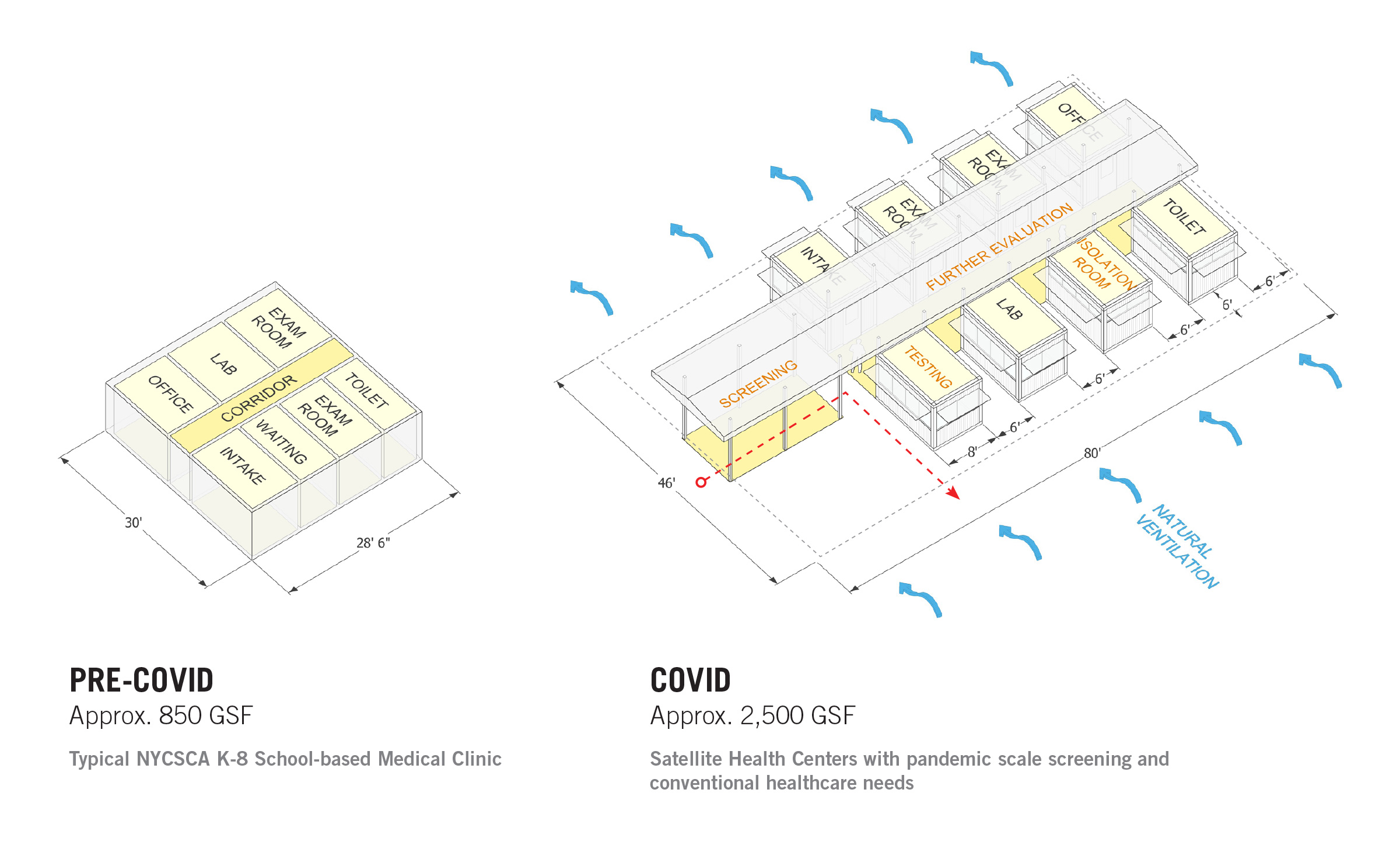

To know what should be provided in a satellite health center, Mitchell Giurgola reviewed the NYCSCA design standard for school-based clinics of which there are 387. Conversely, there are approximately 1,400 schools little more than an office for a school nurse and possibly an examining room and supplies.

A test program was developed based on the SCA 750 NSF school-based medical clinic ramped up to accommodate pandemic-related screening and testing, an isolation room and basic lab. The footprint of the temporary clinic grew considerably to provide social distancing, minimal interaction among people and ample natural ventilation.

Test program developed based on the SCA 750 NSF school-based medical clinic to accommodate pandemic-related screening and testing.

The concept for the design of appropriate temporary and mobile structures is founded on the principle “don’t try to reinvent the wheel”. A brief survey of the industry shows many off-the-shelf rugged, versatile, energy-efficient portable buildings. They are becoming easily available to be purchased off the shelf or leased.

Aside from its benefits to Covid-related screening and testing, facilities like this could become a great benefit to local communities by providing access to a broad range of health services. Utilizing GIS mapping allows agencies to process complicated challenges concerning access into straightforward solutions. Merging healthcare and learning at primary and secondary schools will have enormous benefits for civic life. Schools will have added importance as anchors to all people in their neighborhoods. Many families who have had no access to healthcare will now have it daily.

Mitchell Giurgola is a New York-based architecture firm that is committed to building with perspective and purpose. Buildings for education, particularly those with highly complex functional requirements, are a hallmark of the practice. Clients include the Rockefeller University, New York University, Cornell University, Weill Cornell Medicine, and Columbia University. The firm has extensive experience designing K-12 facilities in the United States and abroad and has worked with the NYC School Construction Authority since 1993.

Using College Campuses as a Community Resource

Prior to the current Covid-19 pandemic, many colleges and universities were facing a crisis of their own: The greatest drop in enrollment in the history of higher education. Plummeting birth rates, a strong economy, and the skyrocketing cost of education were the main culprits. In response, many of these institutions revised their missions, aiming to become more than a vehicle for simply delivering education. Campuses evolved into research centers, tech incubators, athletic powerhouses, corporate training grounds, and arts and entertainment destinations.

But now, with the pandemic disrupting on-campus activities, creating an even more uncertain future, colleges and universities risk the bottom falling out once again. With no or few students on campus, there is a clear need to evolve missions even further. For institutions of higher education, a successful pandemic recovery may depend on their ability to retool themselves into large-scale community resource centers.

Institutional leaders have the resources at hand to provide critical counseling and training services to their surrounding communities, to open up their facilities as workspaces and childcare centers, and to activate their campuses as spaces for public wellness and recreation – filling critical gaps in municipal services in the process.

Why College Campus’ Matter

As with many large institutions, colleges and universities are quite literally invested in their communities – often to a greater degree than even the federal government — and vice versa. New York City, for example, is home to over 100 higher education institutions employing nearly 70,000 people, supporting local businesses, providing health care and research centers, community leadership, and a vast array public open spaces and programs. Across the country, these institutions are critical employers and service providers, and they in turn depend on a healthy local workforce in order for their own operations to function.

When it comes to ensuring the health and wellbeing of local or regional populations, colleges and universities also hold a tremendous number of highly tangible resources within their campuses. Many of these are physical: With partial- or fully distant learning and dipping enrollments a growing trend, they have excess facility space that is well suited for flexible co-working or expanded child support and daycare services; they are also already equipped with concentrated outdoor spaces and social areas appropriate for social distancing, an urban design imperative and also a challenge for many communities, especially in urban areas.

To use New York as an example, in the context of the pandemic: There are dozens of institutions – with athletic fields, green space, etc. – in disadvantaged and disproportionately affected communities where accessible public space is otherwise limited.

As cornerstones of their surrounding communities, college and university campuses also represent readily identifiable sites that can be activated for important services – creating an ecosystem of daily needs that people will search for, all in one (relatively) geographically bound location. These institutions already have expertise well suited to assist the local population in a failing economy – continuing education, career services, small business expertise, community affairs, and more.

In adapting and opening these services to the broader community, colleges and universities can also use their campuses to alleviate burdens that might otherwise come with accessing services in disparate locations: Someone who needs tax help could drop a child off at a daycare facility just minutes away, for instance, and then take advantage of a plaza or other open space afterwards for relaxation.

How college campuses can be retooled

It is clear that colleges and universities have the potential to offer their resources in a time of need to help maintain or improve quality of life and elevate economic opportunities for area residents. What forms might this take?

As noted, above, there is significant opportunity in the notion of on-campus community workspaces. If businesses continue to rely on work from home models in the immediate, midterm, and longer-term post-Covid world, people will increasingly seek work-friendly “third places” that are close to home, close to their kids’ school, close to open space, amenity rich, and populated by other humans.

With a potential increase in hybrid K-12 school models testing the limits of flexible scheduling when schools reopen, it seems likely that the spatial nature of many college and university campuses – physically embedded within their communities — will serve this need well.

Similarly, campus facilities are set up as advanced learning environments — with media rooms, cutting-edge IT systems and other infrastructure – that makes them ideally equipped to handle all different kinds of work. There is also potential for on-campus workspaces to receive funding through corporate sponsorship by companies looking to drastically downsize their own footprints. Barclays and Google have stated such, and corporate sponsorship on campuses was a growing trend well before the pandemic.

In addition to co-working-style services, there are also opportunities for colleges and opportunities to leverage existing resources and provide expert support for individuals and small businesses. The skills needed to help a graduate student launch a business are similar to those that can help an established local business get back on its feet during this pandemic recovery.

This is not a new phenomenon: The business school at Drury University in St. Louis, where Cooper Robertson recently developed a campus master plan, has long provided free tax filing support for the surrounding community. But now, the need for these services will expand dramatically. As PPP loans expire and as local businesses need more personal attention and support — beyond just cash to stay afloat — college and university experts are in a unique position to help. Partially this is because all levels of government are overwhelmed and unequipped.

It is also because colleges and universities can provide services in a centralized location, and have an on-the-ground perspective and understanding of the unique needs of a particular neighborhood, municipality, or region. There are already good examples of institutions creatively combining continuing education, career services, small-business expertise and community affairs to support local businesses – for instance, the University of Wisconsin’s Small Business Development Center.

In terms of workforce preparedness, colleges and universities also have much to offer in the pandemic recovery period. If a major infrastructure plan is to be enacted in the next several years, as many national leaders have suggested, colleges and universities are the largest providers of continuing education, a critical asset in retooling the country’s workforce for the next new deal. For decades, in fact, these institutions have been where private industry turns for advanced manufacturing and workforce education training.

Many institutions already have industry partnerships that may prove essential to economic recovery – for instance, community college campuses nationwide hold custom-built, advanced manufacturing equipment, donated by companies who partner with campus administrators to shape curriculums and create a workforce pipeline. Any new large-scale investment in infrastructure or manufacturing is likely to activate these campus facilities and services to an even greater degree, opening up opportunities for local or regional residents to receive new training and to learn important new skills.

And, of course, college and university campuses can also become critical centers for community wellness and recreation. Childcare facilities, for example, already exist on most campuses as an important resource for students, faculty, and staff alike. With many daycare and childcare centers closed down in the wake of the pandemic, there is a clear opportunity for colleges and universities to expand these services. One path might be to leverage early childhood education grants, available through many state governments.

In terms of recreation, college and university campuses are not only places to walk, run, and bike, but they are often local resource centers for regional recreation — offering programs, public health guidance, equipment rentals, and training. Community needs for these offerings will only expand in the near-term future, as people continue to seek safe places to be outdoors and be outside.

In this time of critical need for institutions and the public alike, the creation of strong and healthy communities is very much in the interest of both town and gown. As major local and regional players with extensive physical resources, it is vital for colleges and universities to think creatively, and find ways to offer resources to populations beyond their student bodies – as a social necessity, and also to ensure their own survival.

The relationship between institutions of higher education and their communities-at-large has always been deeply symbiotic; now is the time to build on this interconnection and foster resilience with meaningful partnerships and positive actions.