Editor’s Note: The Forum for Urban Design is embarking on a campaign to collect ideas for compelling projects, plans, and policies to better New York City under the next mayor’s tenure. To tie in with this theme, the Urban Design Review will be featuring lessons from pioneering global cities. ‘City Government for the New Urban World’is the second entry in this series.

The 21st century city stands poised to play a critical role as a great problem solver and generator of prosperity. We are discovering that only dense cities can reduce our heavy environmental footprint and address the devastating progress of climate change. We are figuring out how to get more out of less, drawing on their inherent capacity to solve multiple problems laterally, not one at a time. And we are embracing Jane Jacobs’ profound insight that cities are not mechanical constructs, but ‘organized complexity’ better understood by analogy with the science of living organisms. But here’s the rub: while this new way of seeing the city is widely shared, we often find that we have inherited systems on auto-pilot that were designed to produce a very different kind of urban world.

Municipal governments are siloed provinces of ‘functional’ specialists who too often pay little heed to the way their work affects the quality of the whole. Planners deal with land use, transportation engineers with moving vehicles, designers with buildings and landscapes, municipal engineers with the arrangement of services and so on. This specialization occurred primarily in the two generations following World War II. By the time the dust settled, we had profoundly reshaped most of the urban environment in North America and many other parts of the world in pursuit of a fragmented, often sprawling, auto-dependent model of zoned homogeneity and functional efficiency. Even though our thinking has changed radically, the ‘siloed’ departmental structure set up to deal with specific problems in isolation too often remains intact.

It is challenging to do innovative city building projects by feeding them into the old bureaucratic stovepipes. Working through these structures can be like using a hammer to turn a screw. Once we accept cities as dynamic, constantly evolving organisms, it is clear that we need a more supple modus operandi, harnessing our new understanding and using digital age interactive tools. It is a little like getting from classical scores to the improvisational qualities of jazz. It will require a “cognitive leap” from the ways things are currently done, a “disruptive technique” which leads to new ways of solving problems and organizing systems.

None of our basic urban challenges exist in isolation. The city needs to be thought of three dimensionally, not just as policies and programs, but as physical places with anticipatory modelling and testing of outcomes. It is critical not to circumscribe problems and opportunities too narrowly–in many cases the meaningful unit of consideration is much larger than the ‘project area’ or even its immediate context. We need to look at the surrounding square miles to truly get all the issues on the table and see the tentacles that extend well outside the boundaries. Underlying social relationships, environmental considerations, economic forces, natural systems, infrastructure and transportation all have their own larger scale logics and do not often fit neatly into planning districts or municipal boundaries.

Cross-sector collaboration is essential as we re-invent our economic base, retool our infrastructure, expand our cultural sector, and plan for an aging population. We cannot deal with transit, traffic, cyclists, pedestrians and the economic vitality of our retail streets in isolation. To be effective in city building we have to get the focus back on the real issues and harness the full power of city design as strategic problem solving in the broadest terms. This means not only using the full capabilities of the design professions but also linking the physical and operational decisions to the economic, environmental and social dimensions of change.

This shift has been occurring in pockets through an intensive empirical process of trial and error that leads from one city to another. We are gradually moving away from compartmentalizing inside and outside municipal government. Instead, we are blending public and private initiatives, working across disciplinary lines and engaging civil society in new ways. Different kinds of knowledge and new skill sets are added to the creative process, including the contributions of designers, planners, engineers, economists and market specialists; environmental scientists, community service providers; civic leaders; artists and arts organizations among others.

In order to fuse all this expertise, it is necessary to create an actual ‘place of convergence’ in City Hall where insights can be pooled and a technique for visualizing overlapping initiatives ‘on the same page’ can be created. Building on my informal experiences with such a model in Toronto, we set up a ‘Design Center’ when I worked with the City of St. Paul. With its own director and a small staff, the design center had a core membership of individuals who worked within City Hall as “city designers” in various capacities, plus a larger ancillary group of staff from the county and other agencies. As we hoped, it has provided a forum where design and city-building issues are discussed by city planners and architects in Planning and Economic Development, landscape architects in the Parks Department, Building Department officials, and transportation and civil engineers in Public Works.

When we kick the tires, pitch new ideas and react to one another, we expand the collective “brain” of the team and, in a sense, simulate the complexity of real-world conditions. The expanded team works together from start to finish – like building the entire car together rather than the fragmentation of the assembly line. Often we discovered that the “solution” in one area actually resides in another.

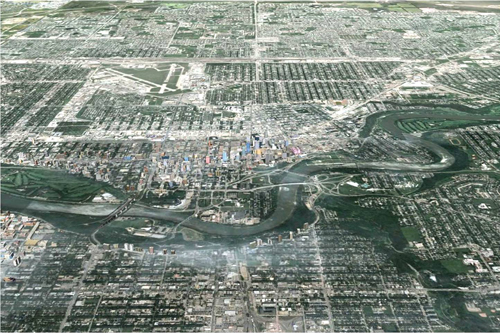

Most recently I have been working with the City of Edmonton, Alberta on two assignments: one to do with the creation of a ‘Connectivity Framework’ to track and frame the evolution of this rapidly growing city, and the other to examine how staff from different disciplines can more effectively integrate their work. At this stage in Edmonton’s evolution, things are moving much too fast for the old paradigm to cope effectively.

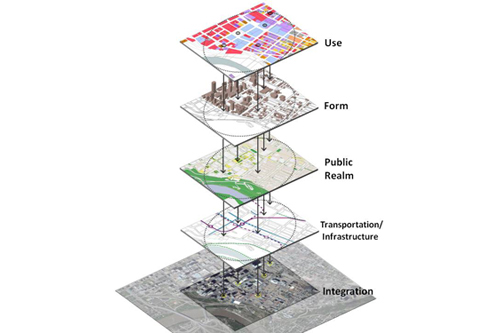

The use of the ‘Framework’ will be a ‘leap’ to get Edmonton from a “good city to a great city.” I have been working with city staff to create a dynamic two and three-dimensional tool that provides an overview of all of downtown plans in time and space. This digital framework depicts the downtown both as it is and how it is evolving, adding even an historical dimension. At once we can examine how historic forces like the river and the removal of rail yards as well as new interventions can be harnessed to help shape the mono-functional CBD into a mixed and vibrant lived-in downtown. This tool shows catalytic projects underway and displays the achievement of the city’s transformational goals in an engaging way.

The Framework will get all layers ‘on the same page,’ much like a Google Map with a zoom feature with the ability to delve down into individual project areas in more detail. It can harness the city’s GIS capabilities to see how the downtown is evolving as a dynamic set of relationships and possibilities, many of which are mutually reinforcing one another including land uses, modal shift, changing demographics and economic metrics. Edmonton may be breaking new ground with this interactive tool. However, to be truly successful, the Edmonton Connectivity Framework must be more than a onetime effort–it must become a living instrument. Aspects of this kind of capability may exist elsewhere but not in this comprehensive form.

The combination of increased appreciation for how cities actually work plus the explosion of new technological advances make this is an ideal time to make the shift toward innovative new ways of city building. The possibilities are limitless. Mid-size cities with motivated leadership may in fact blaze the trail for cities around the world. Projects like the Edmonton Framework initiative and the St. Paul Design Center are worth replicating in larger cities with more sophisticated bureaucracies. Only then can we switch off the auto-pilot.