The Urban Design Forum hosted its eighth Global Exchange: Private Development, Public Good event about the West Kowloon Cultural District (WKCD), an international arts hub rising along 40 hectares of infill land in Victoria Harbour, Hong Kong. Financed by a $2.8 billion public endowment, the project consists of an expansive public park and 17 planned venues, including a new visual arts museum, an opera house, and an experimental performance venue.

Before the off-the-record event, Urban Design Forum Executive Director Daniel McPhee sat down with Duncan Pescod, Chief Executive Officer of WKCD, for a wide-ranging discussion about the project’s financing and design, extensive public engagement efforts, and the future of WKCD in light of recent protest movements in Hong Kong.

Daniel McPhee: When fully built out, what will the West Kowloon Cultural District look like?

Duncan Pescod: The vision is to become not just a domestic cultural center, but a regional cultural center that serves the Greater Bay Area [of the Pearl River Delta] and beyond in Asia. It’s already starting to have that impact. When we opened Xiqu Center—which is our Chinese opera facility—at the beginning of 2019, many people from the mainland came to see performances because we’re bringing in the best performers from China and beyond.

By the time we’ve built out the new cultural facilities, including two museums, the parks, the playgrounds, plus all the commercial hotels and offices, you will have a center in the heart of Hong Kong which provides a whole range of cultural and arts facilities—performances to exhibitions, formal and informal. For example, we’re trying to encourage street performers to produce a lively atmosphere. Something on this scale and ambition will be transformative—it takes time, but it also will have that impact.

DM: It’s situated on an interesting site: a major new waterfront precinct adjacent to the new high-speed rail station. What is the history of the project?

DP: The site was created on reclaimed land created as part of the “Airport Core Project” for the new Hong Kong airport, which opened in 1998. Around that time, the government questioned what to do with this extra piece of land, before deciding to make it an investment in the future, rather than more offices and housing. At that time, there was a big debate about protecting the harbor—making it less of a functional, working harbor, and more of a recreational harbor. The two things came together and the debate was whether to build something touristic or cultural.

If you look at the economic benefit to Hong Kong, we’re investing heavily in the financial sector; we have a strong port sector; and now we can have tourism and creative industries as a third pillar. I was at the Tourism Commission at the time and part of that debate. In a sense, I’ve been involved indirectly and directly since the earliest days.

The Art Park at West Kowloon Cultural District

DM:The project has changed pretty significantly since its initial conception. Can you talk about how the program has changed in particular?

DP: The project initially intended to be commercially-driven, with a single developer given the entire site and required to deliver on cultural and arts facilities. The community didn’t really shine to that at all. They felt that was giving too much influence to the commercial elements. That proposal failed essentially because of community objections.

Then, the government went back to the drawing board and decided that they would create the Authority to take the lead and develop the cultural and arts facilities while still involving developers by selling off the commercial elements of the site.

DM: On a project of this scale, do you need community consultation from just its neighbors—the people in the surrounding community—or from the city at large?

DP: We need both. For example, we have a consultation panel, on which I have local district counselors. But I also have people from the arts community and academics.

DM: You mentioned that there at least one major rewriting of the plan.

DP: Yes—in the sense that it went in one direction first, and then it changed to another. And then, in addition, the development plan as agreed has been revisited a number of times. One would expect that anyway over the period of ten years since the plan was adopted.

DM: But the basic premise that it should be really about culture and recreation has never been challenged?

JN: Never challenged. It’s still fundamental. The government took a view, and they stuck to it. It’s not like the U.K. model where every four or five years you change the government and everything changes. So far, fingers crossed, we have a consistency in our approach.

Creative industries give you an opportunity to see future employment growth on a scale that many other industries will not.

If you look around in China and in Asia, there’s a lot of investment in culture and arts now because people really appreciate it. There are going to be big challenges in terms of employment with increasing use of Artificial Intelligence, robotics, etc. Where are the jobs going to come from? Creative industries give you an opportunity to see future employment growth on a scale that many other industries will not. Even banking! We’ve invested a lot in insurance and banking, and now it’s all going towards Artificial Intelligence. We had have to come up with something new.

DM: Even New York’s jobs plan focuses largely on the creative industries. Can we talk about the financing of the project? I know that originally in the early 2000s it was supposed to be delivered largely by private financing and partners with this commercial mix. Since then, the public sector has taken on a large share of the financing.

DP: Yeah, as I said before, the original plan was that it would be a single developer who would build everything and take the profit out when he could. That was absolutely rejected because the community didn’t like it. So that died very quickly.

The government then came up with the idea of injecting the value of the land capitalized, which would then deliver the cultural elements of the project. So they created the Authority and the government injected 21.6 billion Hong Kong dollars into the project. The problem was they didn’t know what the development plan would be. They didn’t know the timeframe. They assumed everything would essentially be built as one. They had assumptions on things like return-on-investment, costs, inflation, etc.

Duncan presenting to the Urban Design Forum

Between 2008 when the Authority was created and 2011 when the development plan was finally set, two key things happened. First, we had the Financial Crisis, so a lot of the financial calculations just went under. And then secondly, they decided on the Foster + Partners plan with this enormously expensive basement component, which had not been funded.

The government then decided to be pragmatic, not requiring us to build everything at once. They also decided that government always provides the public infrastructure, like roads and sewers, so they agreed to fund the core and shell of the basement.

Then the big question emerged: what do we do to fund the rest of the cultural and arts facilities? We’re going to have to do capital campaigns and all of those things that are familiar to you in the United States.

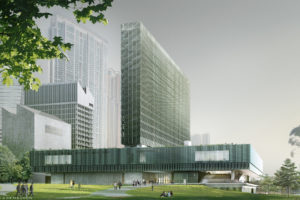

Herzog & de Meuron’s design for the M+ Museum

DM: As we’re exploring how to do a waterfront project like this in New York, we’ll have to think about a couple of things. One is, how would we structure an authority? Two is, how can we finance this and what share has to be private?

Do you think Hong Kong’s Build-Operate-Transfer model one that’s worth exporting?

DP: We’re trying it now. And it’s working on our first commercial project—we’ve just done an expression of interest. And we’ll probably put the tender out next month. It’s a $10 billion dollar plus project from our estimation. I think it is a viable proposition insofar as the developers wouldn’t have come on board if they didn’t think they’d make a profit out of it. In this particular one, we’ve packaged the exhibition center with a hotel in an office complex to make it viable. Most of the other sites will be for a plot for office development, or a hotel as an individual project. The tender process is scheduled to be completed in Q4 2020. Targeted project completion is 2025/2026. Ask me in six months how it turns out.

DM: And how would you advise us on the kind of mix that you’ve been able to achieve: was it the right mix of culture and commercial?

DP: Honestly, it’s evolving. We’re focused primarily on the cultural and arts delivery first. Honestly, that’s not the best way to do it. You have to do both in parallel. But because that is the priority given to us by the government, we have to do it this way. At least we’ll have a sort of a nucleus in the district.

There are many different elements that you need to think about. For example, one of the key elements is to what extent do you need the ‘creatives’ in the district. We’re not like Barcelona, where you’re using culture to regenerate an existing district. We don’t have anything. We are trying to bring in all of the disparate elements, not just the performers who are offering a finished product, but the artists that are creating that product.

We’re looking at hosting resident companies. We’re looking at building artist residencies, so people can live and create within the district. We’re also looking at developing education facilities. We’re looking at not just being a venue for hire.

It’s a tenuous mix of different elements that you’re trying to cram together to create the whole, and it’s proving more difficult in some ways than people expected because it is artificial. It takes time to build momentum. You’ve got to keep pushing, because people in the artistic sector don’t really understand what we’re trying to do. At the same time, we’re trying to push something that no one else is doing.

The recently completed Xiqu Centre for traditional Chinese opera

DM: So, can you talk a little bit about the cultural mix? Domestic vs. regional vs. international—what was the most important to prioritize?

DP: You’ve got to try and balance the two. To be honest with you, though we have strong domestic artistic qualities, they’re not very well known beyond Hong Kong. And to a certain extent that’s limited their ability to develop. So, we’ve been working with local artists to take them abroad. Yet we are always leading with the understanding that this is a Hong Kong project. How does it benefit either the audience, or performers, or future trainees?

DM: Hong Kong is a city that’s grappling with this tension in more ways than just on the West Kowloon site. How has Hong Kong’s recent political movement shaped the way that you are thinking about the future of the cultural district?

DP: Honestly, it’s reinforcing the need. The one thing that is underpinning a lot of the debate in the community, leave aside the violence, is this notion of protecting fundamental freedoms: freedom of expression, freedom of association, freedom from trouble and all of that. What do we represent if not that? Our internal conversations consider: how do we prepare ourselves such that when things returned to a “new normal,” we’re ready to really contribute to that new normality?

We are actively trying to keep things as steady as we can. We’re running programs even though there’s chaos in the streets! The philosophy we have the show must go on. We’ve got to provide an alternative to people if they’re scared of going out on the streets. People come to us and it should be safe.

We had to adapt. We basically just do matinee performances now. We don’t want people to be trying to get home and have their transport disrupted. And we’re continuing to build and explore development opportunities.

Duncan Pescod in conversation with Luke Fox (KPF) and Vincent Chang (Grimshaw)

This is not the best time to put out a major development package—the private sector is very constrained by the situtation. But we feel it’s important to do. If we delay this project, then it’ll be too late when it’s needed.

There is a debate surrounding what exactly will be the outcome. I don’t have a crystal ball. But the one thing I think is true is that the artistic community has been at the forefront of a lot that’s been going on in Hong Kong. We give can give them a space other than the streets to explore. We don’t have to be subject to the political implications. We can look at it purely through an artistic lens.

DM: It does seem like the true success of the project is going to be seen in the next few years when the “new normal” is being expressed and challenged and rearticulated.

DP: Artists will be at the forefront of whatever it is. They are generally ahead of the rest of the community in how to express expressing themselves. If we can give them a decent opportunity to express themselves, that’s going to be really cool for for Hong Kong. It will be a place where the debate can be taking place in a safe fashion. It doesn’t have to be out on the streets against the police—it can be done in a more civil environment, for want of a better description. Art allows for that.

For more information about the West Kowloon Cultural District, please visit their site.

Image Credits: (1) Google Earth (2) WKCD Authority (3) Urban Design Forum/Samuel Lahoz (4) Herzog & de Meuron (5) WKCD Authority (6) Urban Design Forum/Samuel Lahoz