Will technology change the shape of our homes? How should technology change the way we build housing?

What Does Smart Home Tech Bring to You?

Aging Better with Technology

Housing Resilience Through Adaptability

What Does Smart Home Tech Bring to You?

In his short story “There Will Come Soft Rains,” Ray Bradbury envisioned an automated house that could wake its inhabitants, cook their breakfast, read them poetry, and bring forth the furniture they needed when they needed it. But when a storm-blown tree branch comes crashing through a wall, bursting a bottle of flammable cleaning solution on the stove, the house fails to fight back:

“Fire!” screamed a voice. The house lights flashed, water pumps shot water from the ceilings. But the solvent spread on the linoleum, licking, eating, under the kitchen door, while the voices took it up in chorus: “Fire, fire, fire!” The house tried to save itself. Doors sprang tightly shut, but the windows were broken by the heat and the wind blew and sucked upon the fire.

All photos from the series “In the Year 2000” by Jean-Marc Côté

Bradbury’s house sounds only remotely out of reach today. Sprinklers and smoke alarms, incidentally, are perhaps the most familiar and influential “smart building” technologies in the United States. Sprinklers lower the death rate in structure fires by 82 percent, and cut the monetary damage to homes and apartments by 65 percent. The National Institute of Standards and Technology credited smoke alarms as “the greatest success story in fire safety” of the past fifty years (though there’s some dispute about causation), relegating most American fire departments to cat-catching for a pension.

It’s the functioning elements of Bradbury’s future house that we are only now reaching, as the Internet permeates both the structural elements of the house—locks, heat, light, plumbing—and appliances like televisions and refrigerators.

But while industry experts expect to see rapid adoption within the next two to four years of “smart home” devices, and the world’s largest corporations have embraced “connectivity” as a strategic goal, there are signs that regular people are a little less enthused about living inside a connected home.

Privacy

In 2014, Panasonic and 18 other companies opened Fujisawa Sustainable Smart Town, a “smart city” development outside of Tokyo. It was on the one hand a testament to the gains that IoT can wring from the urban environment for generalized social gains. Energy efficiency is paramount, and every resident gets personal reports with advice on energy consumption habits. Fujisawa SST also plans to feature more personal innovations like a digital mirror to brief residents on weight gains and sleeping patterns.

When Panasonic broke ground on a similar project, a hub for its enterprise division outside Denver (the mile-high city beat out 21 competitors with its offer of good site and subsidy), the company left out many Japanese innovations. Americans weren’t ready, the company thought. “You have to make sure citizens are cool with having ‘eyes on,’” Jarrett Wendt, the company’s vice president for strategic initiatives, told me last year. “It’s a bogeyman, because in most big cities there are cameras on anyway, but citizens don’t realize it.”

Cities like that these collaborations can introduce new cost-saving technology, especially in lighting and other utilities. But they also like playing host for a technocratic utopia. Denver isn’t the only city to jump at an opportunity to partner with a Smart City corporation. Kansas City has a similar partnership with Cisco that it hopes will provide smart-city data to local entrepreneurs. Most civic power players like the idea of the city as laboratory, and their development as experiment.

Cities like that these collaborations can introduce new cost-saving technology, especially in lighting and other utilities. But they also like playing host for a technocratic utopia. Denver isn’t the only city to jump at an opportunity to partner with a Smart City corporation. Kansas City has a similar partnership with Cisco that it hopes will provide smart-city data to local entrepreneurs. Most civic power players like the idea of the city as laboratory, and their development as experiment.

That’s the pattern: While corporations and cities charge forward with surveillance, data mining, and connected infrastructure, citizens lag behind.

It’s partly, as Panasonic gleaned, because of concerns about privacy. We’re only just learning how the powers of connected devices will be deployed. In March, the Vault 7 leak revealed that the CIA had developed a program called “Weeping Angel” to use Samsung “smart” televisions as covert surveillance devices. Police responding to a murder in Bentonville, Arkansas discovered a home equipped with a Nest thermostat, a Honeywell alarm system, and an Amazon Echo. The Echo’s “always listening” functionality may play a key role in the murder trial.

Difficulty

While smart home devices like the Echo or the Samsung “smart” TV can be purchased and turned on by anyone, the more influential features of the smart home must be installed. Eager to be cutting edge and seeking (like corporations and cities) the marginal mass savings afforded by smart tech, developers are now building smart thermostats into new buildings.

But most Americans live in older homes that are either incompatible with new technology or must be retrofitted to accommodate it. “If people can’t set the time on their VCR then setting up a wireless connection to a water sensor in a wall is not necessarily the easiest thing to do,” John Lucker, a principal at Deloitte who analyzes the IoT market, explained.

Venture capital money is pushing companies to get products to market, sold, and installed. But manufacturing and sales often outrun quality control, programmatic integrity, and cybersecurity, Lucker said. As companies with VC-backed balance sheets surge into the market, only to fizzle out when funding runs out, consumers risk finding that new tech installed at great cost is now unsupported, useless, or trafficking in metrics that the industry no longer uses.

Venture capital money is pushing companies to get products to market, sold, and installed. But manufacturing and sales often outrun quality control, programmatic integrity, and cybersecurity, Lucker said. As companies with VC-backed balance sheets surge into the market, only to fizzle out when funding runs out, consumers risk finding that new tech installed at great cost is now unsupported, useless, or trafficking in metrics that the industry no longer uses.

This churn is a societal problem, as thousands of new unsecured ports make systems vulnerable. In October, an attack that brought down much of the American internet originated and spread through IoT-connected cameras, baby monitors, and Wi-Fi routers. But it’s also a personal problem, as when a glitch with Google Nest thermostats turned off the heat in an untold number of homes last winter—the latest in a series of snafus involving software updates to the product. Even HVAC professionals have trouble managing the devices.

Money

The current technological landscape is characterized by the competing desires of companies and consumers. Consider the push for voice-based user interfaces (though texting has virtually abolished talking on the phone, and employees would rather Slack then chat out loud), or the massive cash investment in video-based media (though millennials are even more likely than previous generations to prefer text-based news).

Smart homes, like pre-roll ads, are considerably more attractive to companies than citizens. Utilities and insurance companies, for example, are excited to attach sensors to your thermostat, pipes, doors and windows. They have already pioneered “telematics” in car and health insurance, where you can lower your premiums if you agree to be monitored on your car dashboard or around your wrist. But what does smart-home tech bring to you besides discounts on insurance and utilities, which must be weighed against large up-front purchase and installation costs? In conversations with millennials about smart home tech, I sensed both optimism and trepidation. Optimism about savings; trepidation about uses.

Smart homes, like pre-roll ads, are considerably more attractive to companies than citizens. Utilities and insurance companies, for example, are excited to attach sensors to your thermostat, pipes, doors and windows. They have already pioneered “telematics” in car and health insurance, where you can lower your premiums if you agree to be monitored on your car dashboard or around your wrist. But what does smart-home tech bring to you besides discounts on insurance and utilities, which must be weighed against large up-front purchase and installation costs? In conversations with millennials about smart home tech, I sensed both optimism and trepidation. Optimism about savings; trepidation about uses.

For the moment, too many “smart” devices are high-cost gimmicks with significant potential downsides. Those Samsung “smart” TVs that the CIA can hack to spy on you? They let you watch multiple shows at once, control the channel with your voice, and use the television as an alarm clock.

We were promised flying cars; we got a television alarm clock.

Aging Better with Technology

In the 2001 Simpsons Halloween special “House of Whacks,” the family gets sold a total home upgrade – the Ultrahouse 3000 – where everything is controlled by a central computer, becoming the ultimate “smart” home. Meaning everything from laundry to their alarms to dinner preparation was controlled by the home’s central computer. When Marge updates the home’s voice to sexy Pierce Brosnan, “Pierce” quickly becomes infatuated with Marge and attempts to kill Homer by sucking him into the garbage disposal that’s part of the kitchen table. The episode was a parody on 2001: A Space Odyssey and Demon Seed, and has always stuck with me as a humorous reminder of the promises and perils of smart home technology.

Scene from “House of Whacks” where the house attempts to kill Homer to get to Marge (Daily Mars)

The concept behind the smart home is rooted in sustainable design and energy efficiency. Using a sensor system embedded within the home and appliances, home or building owners can control and monitor home energy, lighting, and appliance usage – realizing lower energy costs, lower carbon-footprints, and, hopefully, a better quality of life. Implementation of smart home technology has evolved alongside mobile phone technology, making it easier for a person to have complete control over their home with their smart devices; from controlling the indoor temperature, being able to see who is at the front door when the bell rings, to programming music of choice to start playing when you enter the door.

Increased sophistication in smart home technologies opens the door to other potential applications that could have positive health benefits. New smart home applications are already being deployed to improve the quality of life for older adults, a segment of the population that is living longer and growing rapidly. Here in New York City, a city that offers one of the best age-friendly initiatives in the world, we can find examples of how smart home technologies are being used to improve the lives of older adults. Selfhelp Community Services is a non-profit social services agency in New York City that operates affordable senior living and senior centers, trains and employees home health aides, and provides other social services to older adults. Selfhelp is one of the largest human services providers in the New York City area, servicing over 20,000 elderly New Yorkers. I spoke to David Dring, the Executive Director of Innovations at Selfhelp Community Services, about how his organization is utilizing technology to help enrich the lives of the older adults: “At a minimum, we do this for our buildings, we wire them for Wi-Fi…technologies, so it is ready for people to be mobile throughout the building with that technology. And as they age in place, we are continuing to look for different opportunities that can take advantage of these technologies to communicate with our health team or a third party health team, in providing them with meaningful telehealth services.”

Additionally, Selfhelp has created something called the virtual senior center, which enables homebound older adults to connect to programming at their senior centers. The goal being to increase social interaction and engagement with those who might be socially isolated. Other promising applications of smart home technology include automation for appliances and locks, as well as daily reminders to take medication, which can improve safety and help those with memory problems. According to David, in-home sensing systems can also monitor people’s movements around the space, helping to alert care givers if someone has fallen or is another critical situation that hinders their mobility. Sensing technology placed in the home that monitors general vital signs, such as heart rate or heat signatures, could replace the need for wearables that might be easily forgotten to be put or taken off in the shower.

Selfhelp’s Virtual Senior Center (Serving Seniors)

Other examples of smart home technology implementation geared at older adults were provided by Scott Code, who works in the Center for Aging Services Technologies at LeadingAge, a national association for aging service providers. In one example, passive sensors placed underneath the bed were piloted and then fully implemented in Terraces of Los Gatos (TLG), a non-profit continuing care retirement community in Northern California. The goal of the bed sensors were to prevent pressure ulcers, falls and develop patient centered care plans. Following a pilot, sensors were installed in all beds in the facility and fairly dramatic outcomes were achieved, including a reduction in facility-acquired pressure ulcers by nearly 100% and a 50% reduction in falls. Referencing an experience he had with a previous employer (Selfhelp), Scott told me about another example of how sensing technology was able to proactively help caregivers identify a potential health condition in one of their clients and get them into care much faster: “For instance, when we had the QuietCare system at Selfhelp, a woman kept getting up in the middle of the night. Normally, she gets up one or two times a night, but with this system, it picked up that, from midnight to 6:00 a.m., she got up eight times, and it sent the social worker an alert. And it ended up that she had a urinary tract infection, and she went to see the doctor right away, and it was taken care of, and she really didn’t get sick. That could have gone on for weeks if this system didn’t pick it up.”

Challenges

Although the potential perils of smart home technology aren’t as grave as those posed to the Simpsons by Ultrahouse 3000, recent cyber-attacks on the “internet of things” has revealed major security concerns with these technologies and how easy it is to break into them. Based on a recent literature review, privacy was found to be one of the top concerns among older adults when it comes to implementation of smart home technologies. David, Scott, and Lindsay Goldman – Deputy Director of Aging in the Center for Health Policy and Programs at the New York Academy of Medicine – echoed this concern but felt that this particular barrier was not insurmountable and that the benefits clearly outweighed the potential risks. The major challenges, from their perspectives, were interface design, the lack of funding to implement these technologies on a broad scale, and equity. According to David, one of the biggest challenges “is sort of the interface design and making it what I consider extremely easy to use and making it self-evident… Privacy is going to be an important factor, but I don’t think of it as being a limiting factor.”

“There’s an equity issue. I think technology has the potential to improve people’s life and can help facilitate increased independence. But it’s a question of how, who, where it’s deployed, how much it costs, and how accessible it is.”

–Lindsay Goldman

Another challenge in implementing smart home technologies with older adults is ensuring that proper education is coupled with the intervention in order to ensure that the intended behavior changes occur. This engagement shouldn’t only happen with the individuals, but with caregivers and family members as well. Scott shared a story with me illustrating what can happen when the proper education and engagement doesn’t occur: “There was a home-care worker that came into an individual’s apartment that had this sensor technology, and there’s a sensor in the bathroom, and the home-care worker kept taking the sensor off the wall because she thought it was taking pictures of her while she was in the bathroom. As a result, it was causing an alert that the older adult might have fallen because there was no motion…You need to educate not only the family, the person living there, but anyone that comes into the home just because they need to know what’s going on and understand the value of it.”

Looking Forward

With a growing older adult population and ongoing advances in sensing technology, the potential applications for smart home technology to promote health and create a better quality of life are enormous. Those I interviewed mentioned that the appearance of voice activated systems on the market, like Amazon Alexa or Google Home, have great potential in this space because they could resolve some of the challenges around interface design (mentioned earlier). Additionally, future areas for growth in this sphere include in-home robotics that would help older adults with daily living activities or the use of holographic/interactive video consoles that could connect physical therapists and doctors to recovering patients in the home, better facilitating physical therapy following a procedure (such as a hip or knee replacement).

Despite the seemingly large potential benefits of these technologies, there will probably not be a big push by city or state governments to develop policies requiring or incentivizing them anytime soon. Larger scale implementation will most likely be championed by healthcare insurance companies as more studies reveal potential health savings from these technologies. For example, Fallon Health, a Massachusetts-based health insurer and care provider, did a 12 month pilot study where they developed a passive remote monitoring system for seniors and demonstrated cost savings of $687 per member per month as a result of the program, which equated to about $8000 in savings per year.

Initial results from studies that evaluate smart home technology for older adults point to a golden opportunity to achieve what’s known as the healthcare triple aim: improving the patient experience of care; improving the health of populations; and reducing the per capita cost of health care. One of the primary tenants of former President Obama’s Affordable Care Act was reducing healthcare costs through technological innovation, whether that be in healthcare delivery, electronic medical records, or new prevention programs. With funding and research support from places like the Innovation Center within the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, we are beginning to see progress on these goals. However, in light of recent federal action by the new administration and Republican-led Congress to repeal the Affordable Care Act, many of these gains and efforts to reduce costs could be lost. For this reason and many more, it is absolutely vital that consideration be given to the most vulnerable among us that could be adversely affected by massive changes to our healthcare system.

Housing Resilience Through Adaptability

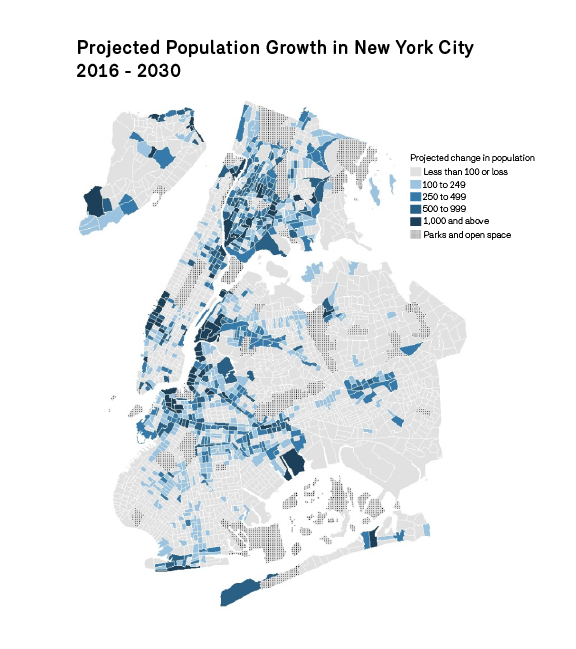

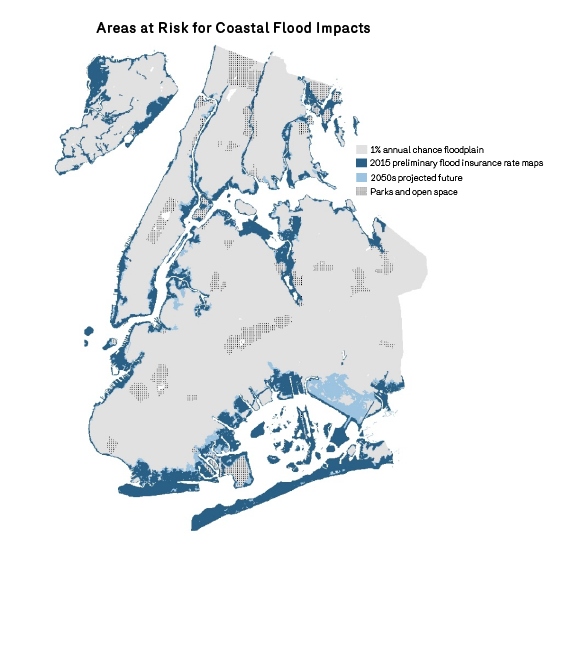

For the first time in decades, more people are moving into New York City than leaving and the population of every borough is increasing. Over the past five years, New York City’s population has grown at the fastest rate since the 1920s, adding 375,000 new residents. By 2040, the City projects that the population will reach 9 million, an all-time high, putting a strain on our housing supply and driving up rents. More than half of New Yorkers are rent-burdened, meaning that they spend more than 30% of their income on rent. Income inequality is also rising with nearly half of the city’s population now living at or near the poverty threshold. Simultaneously, the realities of climate change require that we protect our city, and particularly coastal areas from rising sea levels and natural disasters. Hurricane Sandy brought the city’s climate vulnerabilities to light, causing $19 billion in damages with a flood inundation zone that encompassed approximately 300,000 homes and 23,000 businesses.

These phenomena necessitate careful consideration of not only increasing housing supply, but also the footprint of that housing. Though some segments of the city’s coastal areas are becoming increasingly precarious for residential uses, the waterfront can also continue to be home to some of the New York’s most vibrant communities through innovative thinking and the deployment of novel building technologies.

These phenomena necessitate careful consideration of not only increasing housing supply, but also the footprint of that housing. Though some segments of the city’s coastal areas are becoming increasingly precarious for residential uses, the waterfront can also continue to be home to some of the New York’s most vibrant communities through innovative thinking and the deployment of novel building technologies.

The outlined multipronged approach unlocks the potential for a planning and construction process that is coordinated and timely, more agile and reconfigurable, quick to deploy, and scalable. Resilience improvements are inherent, while improved affordability is a secondary result of decreasing stress on the housing market by increasing flexibility and thereby the number of housing units that could be compatible to a given resident or household. Though there are challenges to implementing this strategy broadly in the city, there are undoubted benefits that New Yorkers could reap by repurposing existing homes to meet evolving needs.

Adaptable housing technology presents an opportunity for New Yorkers in coastal communities to build flexibility into their homes that will maximize affordability and resilience by enabling evolving use over time. Broadly defined as housing that can adjust to changing technological needs and environmental patterns, adaptable housing represents a departure from traditional notions of housing structures as static and the potential to build affordability and resilience in housing stock by reducing the rigidity of the built environment.

The potential of adaptable housing in New York City

Adaptable housing has appeared in New York City in many forms, primarily for social and economic reasons. For example, the practice of adding walls or temporary dividers to split rooms has long been an informal means of adapting spaces to accommodate a growing family or to increase occupancy for cost-savings. However, advances in adaptable building technologies could now also be utilized for increased housing resiliency, including for single and multi-family buildings. New construction techniques, alternative materials and innovative technologies enable us to retrofit old, and design new, buildings and structures to withstand the current and predicted impacts of climate change.

Using a combination of pre-fabrication, modular construction, and technologies for sensing and actuation, there is potential to broaden the areas being considered for housing development, while maintaining the safety and well-being of New Yorkers. Pre-fabrication methodologies have higher precision, lower cost, and faster speed of construction than traditional in-situ construction and have been used successfully for residential uses in Scandinavia and Japan.

Using a combination of pre-fabrication, modular construction, and technologies for sensing and actuation, there is potential to broaden the areas being considered for housing development, while maintaining the safety and well-being of New Yorkers. Pre-fabrication methodologies have higher precision, lower cost, and faster speed of construction than traditional in-situ construction and have been used successfully for residential uses in Scandinavia and Japan.

However, in the United States, pre-fabrication has tended largely toward commercial development. Modular construction provides a standardized interface for different building components that are built upon a baseline chassis that includes all required mechanical and electrical subsystems. Varying components can be assembled onto the chassis to either reconfigure existing components or add additional building components as required for expansion. These components can be shifted at relatively low-cost in response to evolving climate conditions or household changes. For example, a growing family whose home faces increasing risks from sea-level rise could have the opportunity to shift modular room components from the ground floor to higher elevations, while also adding an additional bedroom. This not only has implications with respect to resilience, but also affordability with inherent cost-savings in avoided real estate transactions and built-in customization tailored to unique needs.

Modularizing building components allows for low-cost disassembly and reconfiguration, allowing not only for climate resilience, but the adaptability for changing household needs as a family evolves.

Finally, integrating state-of-the art sensing and actuation technologies to control building systems can enable quick understanding and response to changing household needs and environmental conditions. These technologies have the potential to aid the management of multi-family buildings by enabling the monitoring of short and long-term environmental trends through the installation of building-specific and neighborhood-based sensors. Having complete information about the risk and frequency of flood events would allow the proprietors of multi-family buildings to plan ahead for any necessary building modifications. Furthermore, real-time sensing data during climate events can assist in triggering automated actuation of mechanical resilience measures such as watertight barriers on ground-levels.

Adaptable housing in context: Far Rockaway

Far Rockaway is uniquely positioned amongst New York City’s neighborhoods to benefit greatly from the implementation of adaptable housing technology at scale. Downtown Far Rockaway has been the focus of recent planning initiatives to promote both economic development and the production of affordable housing. Simultaneously, a vast portion of larger Far Rockaway, including primarily residential area falls within the flood plain. In order for plans for Downtown Far Rockaway to fully come to fruition and meet their envisioned potential, the future resilience of residential development in the immediate surrounding areas must be carefully considered.

A vision for downtown Far Rockaway by the NYC Economic Development Corporation

Dwelling units in Far Rockaway are comprised of mostly 1 to 2-family attached and detached units with low-rise multi-family residences distributed throughout. This low-density development necessitates an approach to adaptable housing technology that is uniquely straightforward within the city, as many residents own their homes and have relative autonomy over modifications to building structures.

Housing typologies in Far Rockaway (Jessica Mathew)

New construction aligning with the typical building typology in Far Rockaway could be modularized to increase flexibility of use on the ground floor and improve the ability for homes to evolve with changing sea-level conditions. Meanwhile, existing structures could be retrofitted within sensing and actuation technology to protect critical utility systems, which are often located on the ground floor of the home.

Modular housing conceptual diagram (by Greg Keeffe and Ian McHugh, Queens University Belfast)

Challenges

However, in order to deploy these building systems broadly in New York City, we must carefully consider the risks of reliance on such technology. There are many considerations involved in creating an appropriate regulatory environment that enables the city to reap benefits while protecting the well-being of residents. Historically, informal adaptation of dwellings has facilitated overcrowding conditions motivated by cost-savings. This creates tremendous public health hazards, particularly from the perspective of the Fire Department which compiles detailed data on building materials, floorplans, and occupancy to respond to fire emergencies. If flexible building technologies are adopted in New York City, the municipal government would have to carefully consider how to track building changes for health and safety. Another challenge would be building sufficient flexibility into zoning regulations to allow for sufficient variances within given bounds. This is already beginning to take place in buildings that use permanent building technology to vacate a ground floor, but must be streamlined for application with more temporary building components.

Looking ahead

There are many potential benefits to putting a policy framework into place to oversee and support adaptable housing technology for improved housing resilience and adaptability in New York City’s coastal communities. By coordinating with private firms to better understand the future of adaptable housing technology, the City will be better equipped to develop a robust policy framework across City agencies including the Department of City Planning, Department of Buildings, and Department of Housing Preservation and Development.